Solstice and Equinox Curriculum 45 to 60 Minutes for 6Th-8Th Grades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

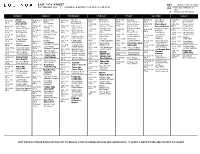

E a S T 7 4 T H S T R E E T August 2021 Schedule

E A S T 7 4 T H S T R E E T KEY St udi o key on bac k SEPT EM BER 2021 SC H ED U LE EF F EC T IVE 09.01.21–09.30.21 Bolld New Class, Instructor, or Time ♦ Advance sign-up required M O NDA Y T UE S DA Y W E DNE S DA Y T HURS DA Y F RII DA Y S A T URDA Y S UNDA Y Atthllettiic Master of One Athletic 6:30–7:15 METCON3 6:15–7:00 Stacked! 8:00–8:45 Cycle Beats 8:30–9:30 Vinyasa Yoga 6:15–7:00 6:30–7:15 6:15–7:00 Condiittiioniing Gerard Conditioning MS ♦ Kevin Scott MS ♦ Steve Mitchell CS ♦ Mike Harris YS ♦ Esco Wilson MS ♦ MS ♦ MS ♦ Stteve Miittchellll Thelemaque Boyd Melson 7:00–7:45 Cycle Power 7:00–7:45 Pilates Fusion 8:30–9:15 Piillattes Remiix 9:00–9:45 Cardio Sculpt 6:30–7:15 Cycle Beats 7:00–7:45 Cycle Power 6:30–7:15 Cycle Power CS ♦ Candace Peterson YS ♦ Mia Wenger YS ♦ Sammiie Denham MS ♦ Cindya Davis CS ♦ Serena DiLiberto CS ♦ Shweky CS ♦ Jason Strong 7:15–8:15 Vinyasa Yoga 7:45–8:30 Firestarter + Best Firestarter + Best 9:30–10:15 Cycle Power 7:15–8:05 Athletic Yoga Off The Barre Josh Mathew- Abs Ever 9:00–9:45 CS ♦ Jason Strong 7:00–8:00 Vinyasa Yoga 7:00–7:45 YS ♦ MS ♦ MS ♦ Abs Ever YS ♦ Elitza Ivanova YS ♦ Margaret Schwarz YS ♦ Sarah Marchetti Meier Shane Blouin Luke Bernier 10:15–11:00 Off The Barre Gleim 8:00–8:45 Cycle Beats 7:30–8:15 Precision Run® 7:30–8:15 Precision Run® 8:45–9:45 Vinyasa Yoga Cycle Power YS ♦ Cindya Davis Gerard 7:15–8:00 Precision Run® TR ♦ Kevin Scott YS ♦ Colleen Murphy 9:15–10:00 CS ♦ Nikki Bucks TR ♦ CS ♦ Candace 10:30–11:15 Atletica Thelemaque TR ♦ Chaz Jackson Peterson 8:45–9:30 Pilates Fusion 8:00–8:45 -

Blood and Mistletoe: the History of the Druids in Britain Free

FREE BLOOD AND MISTLETOE: THE HISTORY OF THE DRUIDS IN BRITAIN PDF Ronald Hutton | 492 pages | 24 May 2011 | Yale University Press | 9780300170856 | English | New Haven, United States Blood and Mistletoe | Yale University Press Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. NOOK Book. Crushed by the Romans in the first century A. Because of this, historian Ronald Hutton shows, succeeding British generations have been free to reimagine, reinterpret, and reinvent the Druids. Druids have been remembered at different times as patriots, scientists, philosophers, or priests; sometimes portrayed as corrupt, bloodthirsty, or ignorant, they were also seen as fomenters of rebellion. Hutton charts how the Druids have been written in and out of history, archaeology, and the public consciousness for some years, with particular focus on the romantic period, when Druids completely dominated notions of British prehistory. Sparkling with legends and images, filled with new perspectives on ancient and modern times, this book is a fascinating cultural study of Druids as catalysts in British history. He lives in Bristol, UK. Home 1 Books 2. Read an excerpt of this book! Add to Wishlist. Overview Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain by the Romans in the first century A. Related Searches. Praise for the author::'For anyone researching the subject, this is the book you've been waiting Praise for the author::'For anyone researching the subject, this is the book you've been waiting for. -

Wicca 1739 Have Allowed for His Continued Popularity

Wicca 1739 have allowed for his continued popularity. Whitman’s According to Gardner, witchcraft had survived the per- willingness to break out of hegemonic culture and its secutions of early modern Europe and persisted in secret, mores in order to celebrate the mundane and following the thesis of British folklorist and Egyptologist unconventional has ensured his relevance today. His belief Margaret Murray (1862–1963). Murray argued in her in the organic connection of all things, coupled with his book, The Witch Cult in Western Europe (1921), that an old organic development of a poetic style that breaks with religion involving a horned god who represented the fertil- many formal conventions have caused many scholars and ity of nature had survived the persecutions and existed critics to celebrate him for his innovation. His idea of uni- throughout Western Europe. Murray wrote that the versal connection and belief in the spirituality present in a religion was divided into covens that held regular meet- blade of grass succeeded in transmitting a popularized ings based on the phases of the moon and the changes of version of Eastern theology and Whitman’s own brand of the seasons. Their rituals included feasting, dancing, sac- environmentalism for generations of readers. rifices, ritualized sexual intercourse, and worship of the horned god. In The God of the Witches (1933) Murray Kathryn Miles traced the development of this god and connected the witch cult to fairy tales and Robin Hood legends. She used Further Reading images from art and architecture to support her view that Greenspan, Ezra, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Whit- an ancient vegetation god and a fertility goddess formed man. -

Summer Solstice

A FREE RESOURCE PACK FROM EDMENTUM Summer Solstice PreK–6th Topical Teaching Grade Range Resources Free school resources by Edmentum. This may be reproduced for class use. Summer Solstice Topical Teaching Resources What Does This Pack Include? This pack has been created by teachers, for teachers. In it you’ll find high quality teaching resources to help your students understand the background of Summer Solstice and why the days feel longer in the summer. To go directly to the content, simply click on the title in the index below: FACT SHEETS: Pre-K – Grade 3 Grades 3-6 Grades 3-6 Discover why the Sun rises earlier in the day Understand how Earth moves and how it Discover how other countries celebrate and sets later every night. revolves around the Sun. Summer Solstice. CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS: Pre-K – Grade 2 Grades 3-6 Discuss what shadows are and how you can create them. Discuss how Earth’s tilt cause the seasons to change. ACTIVITY SHEETS AND ANSWERS: Pre-K – Grade 3 Grades 3-6 Students are to work in pairs to explain what happens during Follow the directions to create a diagram that describes the Summer Solstice. Summer Solstice. POSTER: Pre-K – Grade 6 Enjoyed these resources? Learn more about how Edmentum can support your elementary students! Email us at www.edmentum.com or call us on 800.447.5286 Summer Solstice Fact Sheet • Have you ever noticed in the summer that the days feel longer? This is because there are more hours of daylight in the summer. • In the summer, the Sun rises earlier in the day and sets later every night. -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

DECEMBER 21 SOLSTICE 2020 a Ritual Practice to Harness This Energy

DECEMBER 21 SOLSTICE 2020 A ritual practice to harness this energy. A R D M O O R E & C O . K A R E N S T E V E N S . C O M . A U D E C E M B E R 2 1 S O L S T I C E 2 0 2 0 There is going to be a great cosmic solar event that will be seen and experienced by every single conscious being in our universe. This is what is commonly being described as the event. Why 21st December 2020? There's natural scientific significance of this date with relation to our solar system. The Azimuthal Equidistant Geocentric Earth model, the sun coils up and around the electromagnetic dome that encapsulates our earth for the summers and coils down towards the end of our solar year to its southern most position of the Tropic of Capricorn. And on December 21 is at its lowest Zenith or Y axis point, the farthest out from our land centre, and the closest to the earth vertically. This is what is known as the winter solstice, from a northern hemisphere perspective, and the summer solstice from the southern hemisphere perspective. K A R E N S T E V E N S . C O M . A U D E C E M B E R 2 1 S O L S T I C E 2 0 2 0 Once the sun has reached its lowest point, it follows the same radiant circuit, and either ascending or descending for three days before then beginning its journey back up to the Tropic of Cancer towards the top in the centre of our electromagnetic dome of this domain. -

SOLSTICE PROJECT RESEARCH a Unique Solar Marking Construct

SOLSTICE PROJECT RESEARCH Papers available on this site may be downloaded, but must not be distributed for profit without citation. A Unique Solar Marking Construct By Anna Sofaer, Volker Zinser, and Rolf M. Sinclair Reprinted with permission from Science, 19 October 1979, Volume 206, Number 4416 pp. 283-291. Copyright 1979 American Association for the Advancement of Science. Readers may view, browse, and/or download this material for temporary copying purposes only, provided these uses are for noncommercial personal purposes. Except as provided by law, this material may not be further reproduced, distributed, transmitted, modified, adapted, performed, displayed, published, or sold in whole or in part, without prior written permission from AAAS. www.sciencemag.org Summary: An assembly of stone slabs on an isolated butte in New Mexico collimates sunlight onto spiral petroglyphs carved on a cliff face. The light illuminates the spirals in a changing pattern throughout the year and marks the solstices and equinoxes with particular images. The assembly can also be used to observe lunar phenomena. It is unique in archeoastronomy in utilizing the changing height of the midday sun throughout the year rather than its rising and setting points. The construct appears to be the result of deliberate work of the Anasazi Indians, the builders of the great pueblos in the area. Near the top of an isolated butte in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, three large stone slabs collimate sunlight in vertical patterns of light on two spiral petroglyphs carved on the cliff behind them. The light illuminates the spirals each day near noon in a changing pattern throughout the year and marks the solstices and equinoxes with particular images. -

Summer Solstice

Summer Solstice The equator is an imaginary line around the middle of the Earth. Above the equator is the northern hemisphere. Below the equator is the southern hemisphere. Can you imagine a pole going through Earth from the North Pole to the South Pole? This pole would be the Earth’s axis. The Earth spins around this axis. The axis is not vertical; it tilts the Earth over. This means the Earth appears to lean over. The Earth orbits or moves on a path around the Sun. This takes around one year. At different times of the year, as it journeys around the Sun, some places on Earth are nearer to the Sun than others. If you live above the equator, Earth is tilted closer to the Sun in the summer, giving more light and heat. In winter, these countries are further away from the sun and have less light and heat. Spring Sun Winter Summer Autumn This diagram shows the seasons in the northern hemisphere, above the equator. Can you see how the northern hemisphere is tilted towards the sun in summer? Page 1 of 3 Summer Solstice What is the Summer Solstice? The Summer Solstice happens when the North Pole is most tilted towards the sun. It marks the change when days in the northern hemisphere begin to grow shorter. The Summer Solstice happens around 21st June. This is also known as midsummer and is the longest day and shortest night of the year in the northern hemisphere. Summer Solstice in the Far North Solstice Celebrations Around the Summer Solstice, countries For thousands of years, there have in the Arctic Circle, like parts of been solstice celebrations around Norway, Finland, Greenland and the world. -

Equation of Time — Problem in Astronomy M

This paper was awarded in the II International Competition (1993/94) "First Step to Nobel Prize in Physics" and published in the competition proceedings (Acta Phys. Pol. A 88 Supplement, S-49 (1995)). The paper is reproduced here due to kind agreement of the Editorial Board of "Acta Physica Polonica A". EQUATION OF TIME | PROBLEM IN ASTRONOMY M. Muller¨ Gymnasium M¨unchenstein, Grellingerstrasse 5, 4142 M¨unchenstein, Switzerland Abstract The apparent solar motion is not uniform and the length of a solar day is not constant throughout a year. The difference between apparent solar time and mean (regular) solar time is called the equation of time. Two well-known features of our solar system lie at the basis of the periodic irregularities in the solar motion. The angular velocity of the earth relative to the sun varies periodically in the course of a year. The plane of the orbit of the earth is inclined with respect to the equatorial plane. Therefore, the angular velocity of the relative motion has to be projected from the ecliptic onto the equatorial plane before incorporating it into the measurement of time. The math- ematical expression of the projection factor for ecliptic angular velocities yields an oscillating function with two periods per year. The difference between the extreme values of the equation of time is about half an hour. The response of the equation of time to a variation of its key parameters is analyzed. In order to visualize factors contributing to the equation of time a model has been constructed which accounts for the elliptical orbit of the earth, the periodically changing angular velocity, and the inclined axis of the earth. -

Research on the Precession of the Equinoxes and on the Nutation of the Earth’S Axis∗

Research on the Precession of the Equinoxes and on the Nutation of the Earth’s Axis∗ Leonhard Euler† Lemma 1 1. Supposing the earth AEBF (fig. 1) to be spherical and composed of a homogenous substance, if the mass of the earth is denoted by M and its radius CA = CE = a, the moment of inertia of the earth about an arbitrary 2 axis, which passes through its center, will be = 5 Maa. ∗Leonhard Euler, Recherches sur la pr´ecession des equinoxes et sur la nutation de l’axe de la terr,inOpera Omnia, vol. II.30, p. 92-123, originally in M´emoires de l’acad´emie des sciences de Berlin 5 (1749), 1751, p. 289-325. This article is numbered E171 in Enestr¨om’s index of Euler’s work. †Translated by Steven Jones, edited by Robert E. Bradley c 2004 1 Corollary 2. Although the earth may not be spherical, since its figure differs from that of a sphere ever so slightly, we readily understand that its moment of inertia 2 can be nonetheless expressed as 5 Maa. For this expression will not change significantly, whether we let a be its semi-axis or the radius of its equator. Remark 3. Here we should recall that the moment of inertia of an arbitrary body with respect to a given axis about which it revolves is that which results from multiplying each particle of the body by the square of its distance to the axis, and summing all these elementary products. Consequently this sum will give that which we are calling the moment of inertia of the body around this axis. -

GSA on the Web

Vol. 6, No. 4 April 1996 1996 Annual GSA TODAY Meeting Call for A Publication of the Geological Society of America Papers Page 17 Electronic Dipping Reflectors Beneath Abstracts Submission Old Orogens: A Perspective from page 18 the British Caledonides Registration Issue June GSA Today John H. McBride,* David B. Snyder, Richard W. England, Richard W. Hobbs British Institutions Reflection Profiling Syndicate, Bullard Laboratories, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0EZ, United Kingdom A B Figure 1. A: Generalized location map of the British Isles showing principal structural elements (red and black) and location of selected deep seismic reflection profiles discussed here. Major normal faults are shown between mainland Scotland and Shetland. Structural contours (green) are in kilome- ters below sea level for all known mantle reflectors north of Ireland, north of mainland Scotland, and west of Shetland (e.g., Figs. 2A and 5); contours (black) are in seconds (two-way traveltime) on the reflector I-I’ (Fig. 2B) pro- jecting up to the Iapetus suture (from Soper et al., 1992). The contour inter- val is variable. B: A Silurian-Devonian (410 Ma) reconstruction of the Caledo- nian-Appalachian orogen shows the three-way closure of Laurentia and Baltica with the leading edge of Eastern Avalonia thrust under the Laurentian margin (from Soper, 1988). Long-dash line indicates approximate outer limit of Caledonian-Appalachian orogen and/or accreted terranes. GGF is Great Glen fault; NFLD. is Newfoundland. reflectors in the upper-to-middle crust, suggesting a “thick- skinned” structural style. These reflectors project downward into a pervasive zone of diffuse reflectivity in the lower crust. -

Earth-Moon-Sun-System EQUINOX Presentation V2.Pdf

The Sun http://c.tadst.com/gfx/750x500/sunrise.jpg?1 The sun dominates activity on Earth: living and nonliving. It'd be hard to imagine a day without it. The daily pattern of the sun rising in the East and setting in the West is how we measure time...marking off the days of our lives. 6 The Sun http://c.tadst.com/gfx/750x500/sunrise.jpg?1 Virtually all life on Earth is aware of, and responds to, the sun's movements. Well before there was written history, humankind had studied those patterns. 7 Daily Patterns of the Sun • The sun rises in the east and sets in the west. • The time between sunrises is always the same: that amount of time is called a "day," which we divide into 24 hours. Note: The term "day" can be confusing since it is used in two ways: • The time between sunrises (always 24 hours). • To contrast "day" to "night," in which case day means the time during which there is daylight (varies in length). For instance, when we refer to the summer solstice as being the longest day of the year, we mean that it has the most daylight hours of any day. 8 Explaining the Sun What would be the simplest explanation of these two patterns? • The sun rises in the east and sets in the west. • The time between sunrises is always the same: that amount of time is called a "day." We now divide the day into 24 hours. Discuss some ideas to explain these patterns.