Binary Pulsar Distances and Velocities from Gaia Data Release 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dunhuang Chinese Sky: a Comprehensive Study of the Oldest Known Star Atlas

25/02/09JAHH/v4 1 THE DUNHUANG CHINESE SKY: A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF THE OLDEST KNOWN STAR ATLAS JEAN-MARC BONNET-BIDAUD Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique ,Centre de Saclay, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France E-mail: [email protected] FRANÇOISE PRADERIE Observatoire de Paris, 61 Avenue de l’Observatoire, F- 75014 Paris, France E-mail: [email protected] and SUSAN WHITFIELD The British Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents an analysis of the star atlas included in the medieval Chinese manuscript (Or.8210/S.3326), discovered in 1907 by the archaeologist Aurel Stein at the Silk Road town of Dunhuang and now held in the British Library. Although partially studied by a few Chinese scholars, it has never been fully displayed and discussed in the Western world. This set of sky maps (12 hour angle maps in quasi-cylindrical projection and a circumpolar map in azimuthal projection), displaying the full sky visible from the Northern hemisphere, is up to now the oldest complete preserved star atlas from any civilisation. It is also the first known pictorial representation of the quasi-totality of the Chinese constellations. This paper describes the history of the physical object – a roll of thin paper drawn with ink. We analyse the stellar content of each map (1339 stars, 257 asterisms) and the texts associated with the maps. We establish the precision with which the maps are drawn (1.5 to 4° for the brightest stars) and examine the type of projections used. -

Determination of the Night Sky Background Around the Crab Pulsar Using Its Optical Pulsation

28th International Cosmic Ray Conference 2449 Determination of the Night Sky Background around the Crab Pulsar Using its Optical Pulsation E. O˜na-Wilhelmi1,2, J. Cortina3, O.C. de Jager1, V. Fonseca2 for the MAGIC collaboration (1) Unit for Space Physics, Potchefstroom University for CHE, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa (2) Dept. de f´isica At´omica, Nuclear y Molecular, UCM, Ciudad Universitaria s/n, Madrid, Spain (3) Institut de Fisica de l’Altes Energies, UAB, Barcelona, Spain Abstract The poor angular resolution of imaging γ-ray telescopes is offset by the large collection area of the next generation telescopes such as MAGIC (17 m diameter) which makes the study of optical emission associated with some γ-ray sources feasible. In particular the optical photon flux causes an increase in the photomultiplier DC currents. Furthermore, the extremely fast response of PMs make them ideal detectors for fast (subsecond) optical transients and periodic sources like pulsars. The HEGRA CT1 telescope (1.8 m radius) is the smallest Cerenkovˆ telescope which has seen the Crab optical pulsations. 1. Method Imaging Atmospheric Cerenkovˆ Detectors (IACT) can be used to detect the optical emission of an astronomical object through the increase it generates in the currents of the camera pixels [7,3]. Since the Crab pulsar shows pulsed emission in the optical wavelengths with the same frequency as in radio and most probably of VHE γ-rays, we use the central pixel of CT1 [5] and MAGIC [1] to monitor the optical Crab pulsation. Before the Crab observations were performed, the expected rate of the Crab pulsar and background were estimated theoretically. -

Constraining the Masses of Microlensing Black Holes and the Mass Gap with Gaia DR2 Łukasz Wyrzykowski1 and Ilya Mandel2,3,4

A&A 636, A20 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201935842 & c ESO 2020 Astrophysics Constraining the masses of microlensing black holes and the mass gap with Gaia DR2 Łukasz Wyrzykowski1 and Ilya Mandel2,3,4 1 Warsaw University Astronomical Observatory, Al. Ujazdowskie 4, 00-478 Warszawa, Poland e-mail: [email protected] 2 Monash Centre for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia 3 OzGrav: The ARC Center of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery, Australia 4 Institute of Gravitational Wave Astronomy and School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK Received 6 May 2019 / Accepted 27 January 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Gravitational microlensing is sensitive to compact-object lenses in the Milky Way, including white dwarfs, neutron stars, or black holes, and could potentially probe a wide range of stellar-remnant masses. However, the mass of the lens can be determined only in very limited cases, due to missing information on both source and lens distances and their proper motions. Aims. Our aim is to improve the mass estimates in the annual parallax microlensing events found in the eight years of OGLE-III observations towards the Galactic Bulge with the use of Gaia Data Release 2 (DR2). Methods. We use Gaia DR2 data on distances and proper motions of non-blended sources and recompute the masses of lenses in parallax events. We also identify new events in that sample which are likely to have dark lenses; the total number of such events is now 18. Results. -

Experiencing Hubble

PRESCOTT ASTRONOMY CLUB PRESENTS EXPERIENCING HUBBLE John Carter August 7, 2019 GET OUT LOOK UP • When Galaxies Collide https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HP3x7TgvgR8 • How Hubble Images Get Color https://www.youtube.com/watch? time_continue=3&v=WSG0MnmUsEY Experiencing Hubble Sagittarius Star Cloud 1. 12,000 stars 2. ½ percent of full Moon area. 3. Not one star in the image can be seen by the naked eye. 4. Color of star reflects its surface temperature. Eagle Nebula. M 16 1. Messier 16 is a conspicuous region of active star formation, appearing in the constellation Serpens Cauda. This giant cloud of interstellar gas and dust is commonly known as the Eagle Nebula, and has already created a cluster of young stars. The nebula is also referred to the Star Queen Nebula and as IC 4703; the cluster is NGC 6611. With an overall visual magnitude of 6.4, and an apparent diameter of 7', the Eagle Nebula's star cluster is best seen with low power telescopes. The brightest star in the cluster has an apparent magnitude of +8.24, easily visible with good binoculars. A 4" scope reveals about 20 stars in an uneven background of fainter stars and nebulosity; three nebulous concentrations can be glimpsed under good conditions. Under very good conditions, suggestions of dark obscuring matter can be seen to the north of the cluster. In an 8" telescope at low power, M 16 is an impressive object. The nebula extends much farther out, to a diameter of over 30'. It is filled with dark regions and globules, including a peculiar dark column and a luminous rim around the cluster. -

EVOLUTION of the CRAB NEBULA in a LOW ENERGY SUPERNOVA Haifeng Yang and Roger A

Draft version August 23, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 EVOLUTION OF THE CRAB NEBULA IN A LOW ENERGY SUPERNOVA Haifeng Yang and Roger A. Chevalier Department of Astronomy, University of Virginia, P.O. Box 400325, Charlottesville, VA 22904; [email protected], [email protected] Draft version August 23, 2018 ABSTRACT The nature of the supernova leading to the Crab Nebula has long been controversial because of the low energy that is present in the observed nebula. One possibility is that there is significant energy in extended fast material around the Crab but searches for such material have not led to detections. An electron capture supernova model can plausibly account for the low energy and the observed abundances in the Crab. Here, we examine the evolution of the Crab pulsar wind nebula inside a freely expanding supernova and find that the observed properties are most consistent with a low energy event. Both the velocity and radius of the shell material, and the amount of gas swept up by the pulsar wind point to a low explosion energy ( 1050 ergs). We do not favor a model in which circumstellar interaction powers the supernova luminosity∼ near maximum light because the required mass would limit the freely expanding ejecta. Subject headings: ISM: individual objects (Crab Nebula) | supernovae: general | supernovae: indi- vidual (SN 1054) 1. INTRODUCTION energy of 1050 ergs (Chugai & Utrobin 2000). However, SN 1997D had a peak absolute magnitude of 14, con- The identification of the supernova type of SN 1054, − the event leading to the Crab Nebula, has been an en- siderably fainter than SN 1054 at maximum. -

Stsci Newsletter: 1991 Volume 008 Issue 03

SPACE 'fEIFSCOPE SOENCE ...______._.INSTITUIE Operated for NASA by AURA November 1991 Vol. 8No. 3 HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS ISSUE: HSTSCIENCE HIGHLIGHTS WF/PC OBSERVATIONS OF THE STELLAR O NEW SCIENCE RESULTS ON M87, CRAB PULSAR CUSP IN M87 O COSTAR PROGRESSING WELL The photograph on the left shows one of a set of images of the central regions of the giant ellipti O ANSWERS TO YOUR QUESTIONS ABOUT HST DATA cal galaxy M87, obtained in June 1991 withHSI's Wide Field and Planetary Camera {WF/PC). 0 CYCLE 2 PEER REVIEW UNDERWAY Analysis of these images has revealed a stellar cusp in the core of M87, consistent with the pres ence of a massive black hole in its nucleus. A combined approach of image deconvolution and modelling has made it possible to investigate the starlight distribution in M87 down to a limiting radius of about 0'.'04 from the nucleus (or about 3 pc from the nucleus if the Virgo cluster is at 16 Mpc). The results show that the central struc ture of M87 can be described by three compo nents: a power-law starlight profile with an r·114 slope which continues unabated into the center, an unresolved central point source, and optical coun terparts of the jet knots identified by VLBI obser vations. In both the V- and /-band Planetary Camera images, the stellar cusp is consistent with the black-hole model proposed for M87 by Young et al. in 1978; in this model, there is a central mas sive object of about 3 x 109 Me. -

Gravitational Waves from Neutron & Strange-Quark Stars

Gravitational Waves From Neutron & Strange-quark Stars • A billion tons per teaspoon: the history of neutron stars. • The discovery of pulsars and identification with NS. • Are NS really strange- quark stars? Supported by the National Science Foundation http://www.ligo.caltech.edu • GWs from NS and SQS. Gregory Mendell • What will we learn? LIGO Hanford Observatory LIGO-G050005-00-W The Neutron Star Idea • Chandrasekhar Supernova 1987A 1931: white dwarf stars will collapse if M > 1.4 solar masses. Then what? • Baade & Zwicky 1934: suggest SN form NS. • Oppenheimer & Volkoff 1939: work http://www.aao.gov.au/images/captions/aat050.html out NS models. Anglo-Australian Observatory, photo by David Malin. (http://www.jb.man.ac.uk/~pul sar/tutorial/tut/tut.html; LIGO-G050005-00-W Jodrell Bank Tutorial) Discovery of Pulsars • Bell notes “scruff” on chart in 1967. • Close up reveals the first pulsar (pulsating radio source) with P = 1.337 s. • Rises & sets with the stars: source is extraterrestrial. • LGM? • More pulsars discovered indicating pulsars are natural phenomena. www.jb.man.ac.uk/~pulsar/tutorial/LIGO-G050005tut/node3.html#SECTION00012000000000000000-00-W A. G. Lyne and F. G. Smith. Pulsar Astronomy. Cambridge University Press, 1990. Pulsars = Neutron Stars • Gold 1968: pulsars are rotating neutron stars. •orbital motion •oscillation •rotation • From the Sung-shih (Chinese Astronomical Treatise): "On the 1st year of the Chi-ho reign period, 5th month, chi-chou (day) [1054 AD], a guest star appeared…south-east of Tian-kuan [Aldebaran].(http://super.colorado.edu/~a str1020/sung.html) http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap991122.html Crab Nebula: FORS Team, 8.2-meter VLT, ESO LIGO-G050005-00-W Pulsars Seen and Heard Play Me (Vela Pulsar) http://www.jb.m an.ac.uk/~pulsa r/Education/Sou nds/sounds.html (Crab Pulsar) Jodrell Bank Observatory, Dept. -

Monthly Notes of the Astronomical Society of Southern Africa

ISSN 0024-8266 mnassa Monthly Notes of the Astronomical Society of Southern Africa Vol 72 Nos 5 & 6 June 2013 mmonthly notes nof the astronomicalas societys of southerna africa JUNE 2013 Vol 72 Nos 5 & 6 Roy Smith (1930 – 2013) 89 G Roberts..................................................................................................................................... Synchronizing High-speed Optical Measurements with amateur equipment A van Staden...................................................................................................................... 91 GRB130427A detected by Supersid monitor B Fraser........................................................................................................................................101 Moonwatch in South Africa: 1957–1958 J Hers........................................................................................................................................... 103 IGY Reminiscenes WS Finsen....................................................................................................................................117 Astronomical Colloquia....................................................................................................... 122 Deep-sky Delights Celestial Home of Stars Magda Streicher................................................................................................................ 127 • AmateurA high-speed photometry • Moonwatch in SA: 1957–1958 • mateu • GRB130427Ar high detected by Supersid monitor • IGY Reminiscenes • GRB -

New Wide Common Proper Motion Binaries

Vol. 6 No. 1 January 1, 2010 Journal of Double Star Observations Page 30 New Wide Common Proper Motion Binaries Rafael Benavides1,2, Francisco Rica2,3, Esteban Reina4, Julio Castellanos5, Ramón Naves6, Luis Lahuerta7, Salvador Lahuerta7 1. Astronomical Society of Córdoba, Observatory of Posadas, MPC-IAU Code J53, C/.Gaitán nº 20, 1º, 14730 Posadas (Spain) 2. Double Star Section of Liga Iberoamericana de Astronomía (LIADA), Avda. Almirante Guillermo Brown No. 4998, 3000 Santa Fe (Argentina) 3. Astronomical Society of Mérida, C/José Ruíz Azorín, 14, 4º D, 06800 Mérida (Spain) 4. Plza. Mare de Dèu de Montserrat, 1 Etlo 2ªB, 08901 L'Hospitalet de Llobregat (Spain) 5. 0bservatory with MPC-IAU Code 939, Av. Primado Reig 183, 46020 Valencia (Spain) 6. Observatory of Montcabrer, MPC-IAU Code 213, C/Jaume Balmes, 24, 08348 Cabrils (Spain) 7. G.E.O.D.A., Observatorio Manises, MPC-IAU Code J98, C/ Mayor, 111-4, 46940 Manises (Spain) Abstract: In this work we report the discovery of 150 new double stars of which 142 are wide common proper motion stellar systems. In addition to this, we report the study of 23 recently catalogued wide common proper motion binaries discovered by other observers. Spectral types, photometric distances, kinematics and ages were determined from data ob- tained consulting the literature. Several criteria were used to determine the nature of each double star. Orbital periods and the semimajor axes were calculated. they are good sensors to detect unknown mass concen- 1. Introduction trations that they may encounter along their galactic For several years double-star amateurs have con- trajectories. -

January 2015 BRAS Newsletter

January, 2015 Next Meeting: January 12th at 7PM at HRPO Artist concept of New Horizons. For more info on it and its mission to Pluto, click on the image. What's In This Issue? President's Message Astro Short: Wild Weather on WASP -43b Secretary's Summary Message From HRPO IYL and 20/20 Vision Campaign Recent BRAS Forum Entries Observing Notes by John Nagle President's Message Welcome to a new year. I can see lots to be excited about this year. First up are the Rockafeller retreat and Hodges Gardens Star Party. Go to our website for details: www.brastro.org Almost like a Christmas present from heaven, Comet Lovejoy C/2014 Q2 underwent a sudden brightening right before Christmas. Initially it was expected to be about magnitude 8 at its brightest but right after Christmas it became visible to the naked eye. At the time of this writing, it may become as bright as magnitude 4.5 or 4. As January progresses, the comet will move farther north, and higher in the sky for us. Now all we need is for these clouds to move out…. If any of you received (or bought yourself) any astronomical related goodies for Christmas and would like to show them off, bring them to the next meeting. Interesting geeky goodies qualify also, like that new drone or 3D printer. BRAS members are invited to a star party hosted by a group called the Lake Charles Free Thinkers. It will be January 24, 2015 from 3:00 PM on, at 5335 Hwy. -

U.S. Naval Observatory Washington, DC 20392-5420 This Report Covers the Period July 2001 Through June Dynamical Astronomy in Order to Meet Future Needs

1 U.S. Naval Observatory Washington, DC 20392-5420 This report covers the period July 2001 through June dynamical astronomy in order to meet future needs. J. 2002. Bangert continued to serve as Department head. I. PERSONNEL A. Civilian Personnel A. Almanacs and Other Publications Marie R. Lukac retired from the Astronomical Appli- cations Department. The Nautical Almanac Office ͑NAO͒, a division of the Scott G. Crane, Lisa Nelson Moreau, Steven E. Peil, and Astronomical Applications Department ͑AA͒, is responsible Alan L. Smith joined the Time Service ͑TS͒ Department. for the printed publications of the Department. S. Howard is Phyllis Cook and Phu Mai departed. Chief of the NAO. The NAO collaborates with Her Majes- Brian Luzum and head James R. Ray left the Earth Ori- ty’s Nautical Almanac Office ͑HMNAO͒ of the United King- entation ͑EO͒ Department. dom to produce The Astronomical Almanac, The Astronomi- Ralph A. Gaume became head of the Astrometry Depart- cal Almanac Online, The Nautical Almanac, The Air ment ͑AD͒ in June 2002. Added to the staff were Trudy Almanac, and Astronomical Phenomena. The two almanac Tillman, Stephanie Potter, and Charles Crawford. In the In- offices meet twice yearly to discuss and agree upon policy, strument Shop, Tie Siemers, formerly a contractor, was hired science, and technical changes to the almanacs, especially to fulltime. Ellis R. Holdenried retired. Also departing were The Astronomical Almanac. Charles Crawford and Brian Pohl. Each almanac edition contains data for 1 year. These pub- William Ketzeback and John Horne left the Flagstaff Sta- lications are now on a well-established production schedule. -

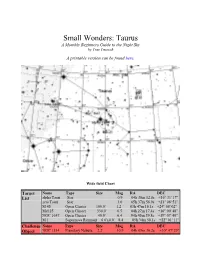

Taurus a Monthly Beginners Guide to the Night Sky by Tom Trusock

Small Wonders: Taurus A Monthly Beginners Guide to the Night Sky by Tom Trusock A printable version can be found here. Wide field Chart Target Name Type Size Mag RA DEC List alpha Tauri Star 0.9 04h 36m 12.8s +16° 31' 17" zeta Tauri Star 3.0 05h 37m 56.9s +21° 08' 51" M 45 Open Cluster 100.0' 1.2 03h 47m 18.1s +24° 08' 02" Mel 25 Open Cluster 330.0' 0.5 04h 27m 17.4s +16° 00' 48" NGC 1647 Open Cluster 40.0' 6.4 04h 45m 59.8s +19° 07' 40" M 1 Supernova Remnant 6.0'x4.0' 8.4 05h 34m 50.1s +22° 01' 11" Challenge Name Type Size Mag RA DEC Object NGC 1514 Planetary Nebula 2.2' 10.9 04h 09m 36.2s +30° 47' 29" A SkyMap Pro Target List for these objects is available. For the last several thousand years, mankind has been a little bull-headed when it comes to Taurus. It has the distinction of being one of the oldest recognized constellations in the night sky. According to some records, it's been in this form for 4000 years or longer. In ancient times, the appearance of the sun in the celestial bull - a plow animal - marked the vernal equinox, and the beginning of spring planting. Our constellation for the month is located on the edge of the winter Milky Way, and our targets include; three open clusters, one of the brightest supernova remnants in the night sky and a lesser known planetary nebula.