Panventriculomegaly with a Wide Foramen of Magendie and Large Cisterna Magna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Saccharomyces Cell Structure

Genetic Techniques for Biological Research Corinne A. Michels Copyright q 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd ISBNs: 0-471-89921-6 (Hardback); 0-470-84662-3 (Electronic) 3 Saccharomyces Cell Structure Saccharomycescerevisiue is aeukaryote and as such containsthe subcellular organelles commonlyfound in eukaryotes.The structure and function of these organelles is fundamentally the same as it is in other eukaryotes with less versatile systems for genetic analysis, and for this reason Saccharomyces is the organism of choice for many cell biologists. For a truly in-depth review of Saccharomyces cell structure and function, the reader is referred to The Molecular and Cellular Biology of theYeast Saccharomyces: Vol. 3: CellCycle and Cell Biology (Broach etal., 1997). The discussion here will provide a very brief overview of the cell structure and will focus on certain unique features of Saccharomyces cell structure in order to facilitate reading of the literature. CELL SHAPE AND GROWTH PATTERNS Underusual culture conditions, Saccharomyces is ellipsoidaUovoid in shapeand approximately 5-10 pm long by 3-7 pm wide. This is referred to as the yeast form. Figure 3.1 shows a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of a cell in the yeast form. Cell division is by budding; that is, a smaller ovoid daughter cell formsas a projection from the surface of the mother cell. Haploid cells are generally about one-half the volume of diploid cells. The characteristic shape is maintained by a rigid cell wall that completely surrounds the plasma membrane of Saccharomyces. Changes in this shape involve remodeling of the cell wall and occur during budding, mating,and pseudohyphal differentiation. -

The Ultrastructure of Spermatozoa and Spermiogenesis in Pyramidellid Gastropods, and Its Systematic Importance John M

HELGOLANDER MEERESUNTERSUCHUNGEN Helgol~inder Meeresunters. 42,303-318 (1988) The ultrastructure of spermatozoa and spermiogenesis in pyramidellid gastropods, and its systematic importance John M. Healy School of Biological Sciences (Zoology, A08), University of Sydney; 2006, New South Wales, Australia ABSTRACT: Ultrastructural observations on spermiogenesis and spermatozoa of selected pyramidellid gastropods (species of Turbonilla, ~gulina, Cingufina and Hinemoa) are presented. During spermatid development, the condensing nucleus becomes initially anterio-posteriorly com- pressed or sometimes cup-shaped. Concurrently, the acrosomal complex attaches to an electron- dense layer at the presumptive anterior pole of the nucleus, while at the opposite (posterior) pole of the nucleus a shallow invagination is formed to accommodate the centriolar derivative. Midpiece formation begins soon after these events have taken place, and involves the following processes: (1) the wrapping of individual mitochondria around the axoneme/coarse fibre complex; (2) later internal metamorphosis resulting in replacement of cristae by paracrystalline layers which envelope the matrix material; and (3) formation of a glycogen-filled helix within the mitochondrial derivative (via a secondary wrapping of mitochondria). Advanced stages of nuclear condensation {elongation, transformation of fibres into lamellae, subsequent compaction) and midpiece formation proceed within a microtubular sheath ('manchette'). Pyramidellid spermatozoa consist of an acrosomal complex (round -

Review of Spinal Cord Basics of Neuroanatomy Brain Meninges

Review of Spinal Cord with Basics of Neuroanatomy Brain Meninges Prof. D.H. Pauža Parts of Nervous System Review of Spinal Cord with Basics of Neuroanatomy Brain Meninges Prof. D.H. Pauža Neurons and Neuroglia Neuron Human brain contains per 1011-12 (trillions) neurons Body (soma) Perikaryon Nissl substance or Tigroid Dendrites Axon Myelin Terminals Synapses Neuronal types Unipolar, pseudounipolar, bipolar, multipolar Afferent (sensory, centripetal) Efferent (motor, centrifugal, effector) Associate (interneurons) Synapse Presynaptic membrane Postsynaptic membrane, receptors Synaptic cleft Synaptic vesicles, neuromediator Mitochondria In human brain – neurons 1011 (100 trillions) Synapses – 1015 (quadrillions) Neuromediators •Acetylcholine •Noradrenaline •Serotonin •GABA •Endorphin •Encephalin •P substance •Neuronal nitric oxide Adrenergic nerve ending. There are many 50-nm-diameter vesicles (arrow) with dark, electron-dense cores containing norepinephrine. x40,000. Cell Types of Neuroglia Astrocytes - Oligodendrocytes – Ependimocytes - Microglia Astrocytes – a part of hemoencephalic barrier Oligodendrocytes Ependimocytes and microglial cells Microglia represent the endogenous brain defense and immune system, which is responsible for CNS protection against various types of pathogenic factors. After invading the CNS, microglial precursors disseminate relatively homogeneously throughout the neural tissue and acquire a specific phenotype, which clearly distinguish them from their precursors, the blood-derived monocytes. The ´resting´ microglia -

Subarachnoid Trabeculae: a Comprehensive Review of Their Embryology, Histology, Morphology, and Surgical Significance Martin M

Literature Review Subarachnoid Trabeculae: A Comprehensive Review of Their Embryology, Histology, Morphology, and Surgical Significance Martin M. Mortazavi1,2, Syed A. Quadri1,2, Muhammad A. Khan1,2, Aaron Gustin3, Sajid S. Suriya1,2, Tania Hassanzadeh4, Kian M. Fahimdanesh5, Farzad H. Adl1,2, Salman A. Fard1,2, M. Asif Taqi1,2, Ian Armstrong1,2, Bryn A. Martin1,6, R. Shane Tubbs1,7 Key words - INTRODUCTION: Brain is suspended in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-filled sub- - Arachnoid matter arachnoid space by subarachnoid trabeculae (SAT), which are collagen- - Liliequist membrane - Microsurgical procedures reinforced columns stretching between the arachnoid and pia maters. Much - Subarachnoid trabeculae neuroanatomic research has been focused on the subarachnoid cisterns and - Subarachnoid trabecular membrane arachnoid matter but reported data on the SAT are limited. This study provides a - Trabecular cisterns comprehensive review of subarachnoid trabeculae, including their embryology, Abbreviations and Acronyms histology, morphologic variations, and surgical significance. CSDH: Chronic subdural hematoma - CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid METHODS: A literature search was conducted with no date restrictions in DBC: Dural border cell PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, Wiley Online Library, Cochrane, and Research Gate. DL: Diencephalic leaf Terms for the search included but were not limited to subarachnoid trabeculae, GAG: Glycosaminoglycan subarachnoid trabecular membrane, arachnoid mater, subarachnoid trabeculae LM: Liliequist membrane ML: Mesencephalic leaf embryology, subarachnoid trabeculae histology, and morphology. Articles with a PAC: Pia-arachnoid complex high likelihood of bias, any study published in nonpopular journals (not indexed PPAS: Potential pia-arachnoid space in PubMed or MEDLINE), and studies with conflicting data were excluded. SAH: Subarachnoid hemorrhage SAS: Subarachnoid space - RESULTS: A total of 1113 articles were retrieved. -

Formation and Structure of Filamentous Systems for Insect Flight and Mitotic Movements Melvyn Dennis Goode Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1967 Formation and structure of filamentous systems for insect flight and mitotic movements Melvyn Dennis Goode Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Goode, Melvyn Dennis, "Formation and structure of filamentous systems for insect flight and mitotic movements " (1967). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 3391. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/3391 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORMATION AND STRUCTURE OF FILAMENTOUS SYSTEMS FOR INSECT FLIGHT AND MITOTIC MOVEMENTS by Melvyn Dennis Goode A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Cell Biology Approved: Signature was redacted for privacy. In Charge oi Major Work Signature was redacted for privacy. Chairman Advisory Committee Cell Biology Program Signature was redacted for privacy. Signature was redacted for privacy. Iowa State University Of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa: 1967 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 PART ONE. THE MITOTIC APPARATUS OF A GIANT AMEBA 5 II. THE STRUCTURE AND PROPERTIES OF THE MITOTIC APPARATUS 6 A. Introduction .6 1. Early studies of mitosis 6 2. The mitotic spindle in living cells 7 3. -

Ochromonas Mitochondria Contain a Specific Chloroplast Protein

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 82, pp. 1456-1459, March 1985 Cell Biology Ochromonas mitochondria contain a specific chloroplast protein (small subunit of ribulose-1,5-blsphosphate carboxylase/immunoelectron microscopy/chrysophycean alga/promiscuous DNA) GINETTE LACOSTE-ROYAL AND SARAH P. GIBBS Department of Biology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A iBi, Canada Communicated by Lynn Margulis, November 1, 1984 ABSTRACT Antibody raised against the small subunit of at 200C in Beijerinck's medium (15) at a light intensity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase [3-phospho-D-glycerate 4300 lux. carboxy-lyase (dimerizing), EC 4.1.1.39] of Chlamydomonas Fixation and Embedding. Cells were fixed in 1% (vol/vol) reinhardtii labeled the mitochondria as well as the chloroplast glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 90 min at 40C, of the chrysophyte alga Ochromonas danica in sections pre- rinsed in buffer and blocked in 2% (wt/vol) agar. The agar pared for immunoelectron microscopy by the protein A-gold blocks were dehydrated in 25% (vol/vol) ethanol at -50C, technique. The same antibody labeled the chloroplast but not then in 50%, 75%, and 95% ethanol at -18'C. Embedding the mitochondria of C. reinhardti. A quantitative study of la- was carried out at -18'C in Lowicryl K4M (16) according to beling in dark-grown, greening (32 hr light), and mature green the following schedule: 95% ethanol/resin, 1:1 (vol/vol), cells of 0. danica revealed that anti-small-subunit staining in overnight; 95% ethanol/resin, 1:2 (vol/vol), 2 times for 2 hr the mitochondria increased progressively in the light as it does each; pure resin, 2 hr and then overnight. -

Chapter III: Case Definition

NBDPN Guidelines for Conducting Birth Defects Surveillance rev. 06/04 Appendix 3.5 Case Inclusion Guidance for Potentially Zika-related Birth Defects Appendix 3.5 A3.5-1 Case Definition NBDPN Guidelines for Conducting Birth Defects Surveillance rev. 06/04 Appendix 3.5 Case Inclusion Guidance for Potentially Zika-related Birth Defects Contents Background ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Brain Abnormalities with and without Microcephaly ............................................................................. 2 Microcephaly ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 Intracranial Calcifications ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Cerebral / Cortical Atrophy ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Abnormal Cortical Gyral Patterns ............................................................................................................................. 9 Corpus Callosum Abnormalities ............................................................................................................................. 11 Cerebellar abnormalities ........................................................................................................................................ -

The Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum in the Repair of Amoeba Nuclear Envelopes Damaged Microsurgically

J. Cell Sci. 14, 421-437 ('974) 421 Printed in Great Britain THE ROLE OF ENDOPLASMIC RETICULUM IN THE REPAIR OF AMOEBA NUCLEAR ENVELOPES DAMAGED MICROSURGICALLY C. J. FLICKINGER Department of Anatomy, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, CharlottesvilU, Virginia 22901, U.S.A. SUMMARY The nuclear envelopes of amoebae were damaged microsurgically, and the fate of the lesions was studied with the electron microscope. Amoebae were placed on the surface of an agar- coated slide. Using a glass probe, the nucleus was pushed from an amoeba, damaged with a chopping motion of the probe, and reinserted into the amoeba. Cells were prepared for electron microscopy at intervals of between 10 min and 4 days after the manipulation. Nuclear envelopes studied between 10 min and 1 h after the injury displayed extensive damage, includ- ing numerous holes in the nuclear membranes. Beginning 15 min after the manipulation, pieces of rough endoplasmic reticulum intruded into the holes in the nuclear membranes. These pieces of rough endoplasmic reticulum subsequently appeared to become connected to the nuclear membranes at the margins of the holes. By 1 day following the injury, many cells had died, but the nuclear membranes were intact in those cells that survived. The elaborate fibrous lamina or honeycomb layer characteristic of the amoeba nuclear envelope was resistant to early changes after the manipulation. Patches of disorganization of the fibrous lamina were present 5 h to 1 day after injury, but the altered parts showed evidence of progress toward a return to normal configuration by 4 days after the injury. It is proposed that the rough endoplasmic reticulum participates in the repair of injury to the nuclear membranes. -

Lateral Atlanto-Occipital Space Puncture

CLINICAL ARTICLE J Neurosurg 129:146–152, 2018 A new method of subarachnoid puncture for clinical diagnosis and treatment: lateral atlanto-occipital space puncture Dianrong Gong, BS, Haiyan Yu, MS, and Xiaoling Yuan, MD Department of Neurology, Liaocheng People’s Hospital, Liaocheng, Shandong, China OBJECTIVE Lumbar puncture may not be suitable for some patients needing subarachnoid puncture, while lateral C1–2 puncture and cisterna magna puncture have safety concerns. This study investigated lateral atlanto-occipital space puncture (also called lateral cisterna magna puncture) in patients who needed subarachnoid puncture for clinical diagnosis or treatment. The purpose of the study was to provide information on the complications and feasibility of this technique and its potential advantages over traditional subarachnoid puncture techniques. METHODS In total, 1008 lateral atlanto-occipital space puncture procedures performed in 667 patients were retrospec- tively analyzed. The success rate and complications were also analyzed. All patients were followed up for 1 week after puncture. RESULTS Of 1008 lateral atlanto-occipital space punctures, 991 succeeded and 17 failed (1.7%). Fifteen patients (2.25%) reported pain in the ipsilateral external auditory canal or deep soft tissue, 32 patients (4.80%) had a transient increase in blood pressure, and 1 patient (0.15%) had intracranial hypotension after the puncture. These complications resolved fully in all cases. There were no serious complications. CONCLUSIONS Lateral atlanto-occipital space puncture is a feasible technique of subarachnoid puncture for clinical diagnosis and treatment. It is associated with a lower rate of complications than lateral C1–2 puncture or traditional (sub- occipital) cisterna magna puncture. -

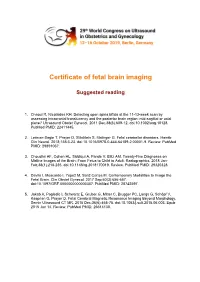

Certificate of Fetal Brain Imaging

Certificate of fetal brain imaging Suggested reading 1. Chaoui R, Nicolaides KH. Detecting open spina bifida at the 11-13-week scan by assessing intracranial translucency and the posterior brain region: mid-sagittal or axial plane? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;38(6):609-12. doi:10.1002/uog.10128. PubMed PMID: 22411445. 2. Lerman-Sagie T, Prayer D, Stöcklein S, Malinger G. Fetal cerebellar disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;155:3-23. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64189-2.00001-9. Review: PubMed PMID: 29891067. 3. Choudhri AF, Cohen HL, Siddiqui A, Pande V, Blitz AM. Twenty-Five Diagnoses on Midline Images of the Brain: From Fetus to Child to Adult. Radiographics. 2018 Jan- Feb;38(1):218-235. doi:10.1148/rg.2018170019. Review. PubMed PMID: 29320328. 4. Davila I, Moscardo I, Yepez M, Sanz Cortes M. Contemporary Modalities to Image the Fetal Brain. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;60(3):656-667. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000307. PubMed PMID: 28742597. 5. Jakab A, Pogledic I, Schwartz E, Gruber G, Mitter C, Brugger PC, Langs G, Schöpf V, Kasprian G, Prayer D. Fetal Cerebral Magnetic Resonance Imaging Beyond Morphology. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2015 Dec;36(6):465-75. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2015.06.003. Epub 2015 Jun 14. Review. PubMed PMID: 26614130. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 29: 109–116 Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/uog.3909 GUIDELINES Sonographic examination of the fetal central nervous system: guidelines for performing the ‘basic examination’ and the ‘fetal neurosonogram’ INTRODUCTION Some abnormalities may be visible in the first and early second trimesters6–11. -

Flagella Apparatus

MOTILE CELL Characters and Character States Location code / cell type ZO, zoospore Flagella apparatus Kinetosome Electron-opaque material in core in kinetosome 0, absent (everything else); 1, present (Kappamyces). Electron-opaque material in axoneme core and between axoneme and flagellar membrane 0, absent; 1, present (many Chytridiales). Kinetosome characters Scalloped ring within kinetosome, extensions of the A, B, or C microtubule Flagellum coating 0, absent; 1, present (Polyphagus euglenae). Number of flagella 0, one 1, multiple Kinetosome-associated structures (KAS) Kinetosome support 0, absent 1, kinetosome props; 2, broken kinetosome props (Olpidium radicale); 3, saddle-like structure surrounding kinetosome (Neocallimastigales) Kinetosome-associated plates 0, absent; 1, present. Kinetosome-associated spur 0, absent; 1, present. Kinetosome-associated shield 0, absent; 1, present. Kinetosome-associated veil 0, absent; 1, present. Anteriorly oriented kinetosome microtubule organizing center (MTOC) (Spizellomycetales) 0, absent; 1, simple solid, not laminate, only one part (Spizellomyces); 2, stacked plates with radiating anteriorly oriented microtubules (Powellomyces) 3, stacked plates with laterally anteriorly oriented microtubules (Gaerteromyces) 4, compound, two in stacked arrangement (Kochiomyces) 5, tripartitalcar rod with 3 lobes in cross-section Primary microtubule roots 0, absent; 1, 2-5 parallel microtubules are stacked with space between them, no connectors (Rhyzophydium); 2, approx. 6-7 parallel microtubules chord-like; 3, more than 20 parallel microtubules, bundled and have connectors/linkers between them (Nowakowskiella); 4, microtubules posterior to anterior, parallel to kinetosome triplets (Batracomyces – not separated like Rhysophydium). Striated rhizoplast 0, absent; 1, present. Flagellar rootlet absolute configuration 0, absent; 1, 20 degrees left; 2, 10 degrees right; 3, 50 degrees left. -

Establishment of a Fungal Model System for the Study of Ciliation

ESTABLISHMENT OF A FUNGAL MODEL SYSTEM FOR THE STUDY OF CILIATION Linnea Tracy June 2015 ESTABLISHMENT OF A FUNGAL MODEL SYSTEM FOR THE STUDY OF CILIATION An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Biology in partial fulfillment of the Honors Program STANFORD UNIVERSITY by Linnea Tracy June 2015 2 Acknowledgements A simple thank-you seems inadequate for all those who have offered their time, expertise, support, and supplies towards my project and education that is culminating in this thesis. Nevertheless, thank you to Tim Stearns, whose kindness, brilliance, and natural knack for teaching was an inspiration to me as a student, was motivation to me as a researcher, and was a great honor to get to know and work closely with over the last two years. Thank you for your time and dedication devoted to my, my peers’, and the world’s education. A special thank you to Erin Turk, who took me under her wing, learning about chytrids in order to teach and assist me, all the while completing her own graduate dissertation. You are one of the most motivated, prepared, and lovely people I have met at Stanford. Thank you for your guidance, mentorship, and always responding to my text messages. Thank you to the members of the Stearns lab, who guided me from learning the basics of the laboratory through experimental design and science writing. It has been, and continues to be, a great pleasure to have a lab family that is so intelligent and kind. I would be remiss to not also thank my parents and friends, who have loyally allowed me to discuss cilia and worry over my experiments with them, sometimes at the expense of our social life.