Norval Morrisseau and the Emergence of the Image Makers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aird Gallery Robert Houle

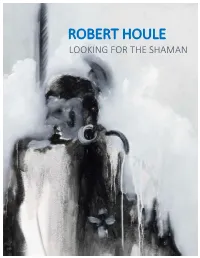

ROBERT HOULE LOOKING FOR THE SHAMAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Carla Garnet ARTIST STATEMENT by Robert Houle ROBERT HOULE SELECTED WORKS A MOVEMENT TOWARDS SHAMAN by Elwood Jimmy INSTALL IMAGES PARTICIPANT BIOS LIST OF WORKS ABOUT THE JOHN B. AIRD GALLERY ROBERT HOULE CURRICULUM VITAE (LONG) PAMPHLET DESIGN BY ERIN STORUS INTRODUCTION BY CARLA GARNET The John B. Aird Gallery will present a reflects the artist's search for the shaman solo survey show of Robert Houle's within. The works included are united by artwork, titled Looking for the Shaman, their eXploration of the power of from June 12 to July 6, 2018. dreaming, a process by which the dreamer becomes familiar with their own Now in his seventh decade, Robert Houle symbolic unconscious terrain. Through is a seminal Canadian artist whose work these works, Houle explores the role that engages deeply with contemporary the shaman plays as healer and discourse, using strategies of interpreter of the spirit world. deconstruction and involving with the politics of recognition and disappearance The narrative of the Looking for the as a form of reframing. As a member of Shaman installation hinges not only upon Saulteaux First Nation, Houle has been an a lifetime of traversing a physical important champion for retaining and geography of streams, rivers, and lakes defining First Nations identity in Canada, that circumnavigate Canada’s northern with work exploring the role his language, coniferous and birch forests, marked by culture, and history play in defining his long, harsh winters and short, mosquito- response to cultural and institutional infested summers, but also upon histories. -

Portraits of Aboriginal People by Europeans and by Native Americans

OTHERS AND OURSELVES: PORTRAITS OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLE BY EUROPEANS AND BY NATIVE AMERICANS Eliana Stratica Mihail and Zofia Krivdova This exhibition explores portraits of Aboriginal peoples in Canada, from the 18th to the 21st centuries. It is divided thematically into four sections: Early Portraits by European Settlers, Commercially-produced Postcards, Photographic Portraits of Aboriginal Artists, and Portraits of and by Aboriginal people. The first section deals with portraits of Aboriginal people from the 18th to the 19th century made by Europeans. They demonstrate an interest in the “other,” but also, with a few exceptions, a lack of knowledge—or disinterest in depicting their distinct physical features or real life experiences. The second section of the exhibition explores commercially produced portraits of First Nations peoples of British Columbia, which were sold as postcards. These postcards date from the 1920s, which represents a period of commercialization of Native culture, when European-Canadians were coming to British Columbia to visit Aboriginal villages and see totem poles. The third section presents photographic portraits of Aboriginal artists from the 20th century, showing their recognition and artistic realizations in Canada. This section is divided into two parts, according to the groups of Aboriginal peoples the artists belong to, Inuit and First Nations. The fourth section of the exhibition explores portraits of and by Aboriginals. The first section sharply contrasts with the last, showing the huge gap in mentality and vision between European settlers, who were just discovering this exotic and savage “other,” and Native artists, whose artistic expression is more spiritual and figurative. This exhibition also explores chronologically the change in the status of Aboriginal peoples, from the “primitive other” to 1 well-defined individuals, recognized for their achievements and contributions to Canadian society. -

Chronology of Daphne Odjig's Life: Attachment #1

Chronology of Daphne Odjig’s life: Attachment #1 Excerpt p.p. 137 – 141 The Drawings and Paintings of Daphne Odjig: A Retrospective Exhibition by Bonnie Devine Published by the National Gallery of Canada in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Sudbury, 2007 1919 Born 11 September at Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve, Manitoulin Island, Ontario, the first of four children, to Dominic Odjig and his English war bride Joyce Peachy. Odjig’s widowed grandfather, Jonas Odjig, lives with the family in the house he had built a generation earlier and which still stands in Wikwemikong today. The family is industrious and relatively prosperous by reserve standards. Jonas Odjig is a carver of monuments and tombstones; Dominic is the village constable. The family also farms their land, raises cows, pigs, and chickens and owns a team of horses. 1925 Begins school at Jesuit Mission in Wikwemikong. An avid student, she turns the family’s pig house into a play school where she teaches local children to read and count. When they tire of her instruction she converts the play school into a play church and hears their confessions. The family is musical. Daphne plays the guitar; Dominic the violin. They all enjoy sing-a-longs and music nights listening to a hand-cranked phonograph. She develops a life-long love of opera singing. She is athletic and participates in the annual fall fairs at Manitowaning, the nearest off-reserve town, eight miles away, taking prizes in running and public speaking. Art is her favourite subject and she develops the habit of sketching with her grandfather and father, both of whom are artistic. -

Norval Morrisseau Work, but Becomes an Imitation When Heritage Society to Compile a It Is Attributed to a Genuine Artist.4 Catalogue Raisonnée

RENDER | THE CARLETON GRADUATE JOURNAL OF ART AND CULTURE FALSIFYING SPIRITUAL TRUTHS: A CASE STUDY IN FAKES AND FORGERIES Kristyn Rolanty, MA Art History Once it has been revealed that painting changes economically, a work of art is faked or forged, our aesthetically, and spiritually. whole set of attitudes and resulting Forgery can be defined in responses change. Forgery implies contrast to notions of originality and the absence of value; but what kind authenticity. In Crimes of the of value are we speaking of? For this Artworld, Thomas D. Bazley defines essay I intend to examine the forgery as the replication of an problematic nature of forgeries, existing artwork or copying of an focusing specifically on the faked and artistic style in an attempt to be forged works of Ojibway artist Norval passed off as an original to acquire Morrisseau. Analyzing a high profile financial gain.1 It is not illegal to copy allegation of forgery, I will explore or imitate an artist’s work, but it themes of authenticity, authorship, becomes so when it is produced with and intent, while attempting to the intent to deceive.2 It is worthy to answer the question: how do note the distinction between a fake allegations of forgery change our and a forgery. A forgery is an exact understanding of a work of art and replica of an existing work, while a why does this matter? I will examine fake is a work in the style of another how our understanding of the artist.3 Both are illegal when represented as authentic. -

Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 143 RC 020 735 AUTHOR Bagworth, Ruth, Comp. TITLE Native Peoples: Resources Pertaining to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1305-6 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 261p.; Supersedes fourth edition, ED 350 116. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; American Indian Education; American Indian History; American Indian Languages; American Indian Literature; American Indian Studies; Annotated Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; *Canada Natives; Elementary Secondary Education; *Eskimos; Foreign Countries; Instructional Material Evaluation; *Instructional Materials; *Library Collections; *Metis (People); *Resource Materials; Tribes IDENTIFIERS *Canada; Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography lists materials on Native peoples available through the library at the Manitoba Department of Education and Training (Canada). All materials are loanable except the periodicals collection, which is available for in-house use only. Materials are categorized under the headings of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis and include both print and audiovisual resources. Print materials include books, research studies, essays, theses, bibliographies, and journals; audiovisual materials include kits, pictures, jackdaws, phonodiscs, phonotapes, compact discs, videorecordings, and films. The approximately 2,000 listings include author, title, publisher, a brief description, library -

Indian Art in the 1990S Ryan Rice

Document generated on 09/25/2021 9:32 p.m. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review Presence and Absence Redux: Indian Art in the 1990s Ryan Rice Continuities Between Eras: Indigenous Art Histories Article abstract Continuité entre les époques : histoires des arts autochtones Les années 1990 sont une décennie cruciale pour l’avancement et le Volume 42, Number 2, 2017 positionnement de l’art et de l’autonomie autochtones dans les récits dominants des états ayant subi la colonisation. Cet article reprend l’exposé des URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1042945ar faits de cette période avec des détails fort nécessaires. Pensé comme une DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1042945ar historiographie, il propose d’explorer chronologiquement comment les conservateurs et les artistes autochtones, et leurs alliés, ont répondu et réagi à des moments clés des mesures coloniales et les interventions qu’elles ont See table of contents suscitées du point de vue politique, artistique, muséologique et du commissariat d’expositions. À la lumière du 150e anniversaire de la Confédération canadienne, et quinze ans après la présentation de la Publisher(s) communication originale au colloque, Mondialisation et postcolonialisme : Définitions de la culture visuelle , du Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, il UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des V reste urgent de faire une analyse critique des préoccupations contemporaines universités du Canada) plus vastes, relatives à la mise en contexte et à la réconciliation de l’histoire de l’art autochtone sous-représentée. ISSN 0315-9906 (print) 1918-4778 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rice, R. -

New Worlds: Frontiers, Inclusion, Utopias

Table of contensNew Worlds: Frontiers, Inclusion, Utopias New Worlds: Frontiers, Claudia Mattos Avolese Inclusion, Roberto Conduru Utopias — EDITORS 1 Table of contens Introduction The Global Dimension of Claudia Mattos Avolese, Art History (after 1900): Roberto Conduru Conflicts and Demarcations [5] Joseph Imorde Universität Siegen [71] Between Rocks and Hard Places: Indigenous Lands, Settler Art Histories and the Perspectives on ‘Battle for the Woodlands’ Institutional Critique Ruth B. Phillips Lea Lublin and Julio Le Parc Carleton University between South America and [9] Europe Isabel Plante Universidad Nacional Transdisciplinary, de San Martín Transcultural, and [85] Transhistorical Challenges of World Art Historiography Peter Krieger Historiography of Indian Universidad Nacional Art in Brazil and the Autónoma de México Native Voice as Missing [36] Perspective Daniela Kern Universidade Federal do Out of Place: Migration, Rio Grande do Sul Melancholia and Nostalgia [101] in Ousmane Sembène’s Black Girl Steven Nelson The Power of the Local Site: University of California, A Comparative Approach to Los Angeles Colonial Black Christs and [56] Medieval Black Madonnas Raphaèle Preisinger University of Bern [116] New Worlds: Frontiers, Inclusion, Utopias — 2 Table of contens Between Roman Models Historiographies of the and African Realities: Contemporary: Modes of Waterworks and Translating in and from Negotiation of Spaces in Conceptual Art Colonial Rio de Janeiro Michael Asbury Jorun Poettering Chelsea College of Arts, École des Hautes Études University of the Arts en Sciences Sociales London [133] [188] Tropical Opulence: Landscape Painting in the Rio de Janeiro’s Theater Americas: An Inquiry Competition of 1857 Peter John Brownlee Michael Gnehm Terra Foundation for Accademia di architettura, American Art Mendrisio / Swiss — Federal Institute of Valéria Piccoli Technology Zurich Pinacoteca do Estado [146] de São Paulo — Georgiana Uhlyarik New Classicism Art Gallery of Ontario Between New York and [202] Bogotá in the 1960s Ana M. -

Download Curriculum Vitae

Dr. DAPHNE ODJIG C.M., O.B.C., R.C.A., L.L.B. Governor General’s Laureate, Visual & Media Arts 2007 Daphne Odjig is a Canadian artist of Aboriginal ancestry. She was born September 11,1919 and raised on the Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve on Manitoulin Island (Lake Huron), Ontario. Daphne Odjig is the daughter of Dominic Odjig and Joyce Peachey. Her father and her grandfather, Chief Jonas Odjig, were Potawatomi, descended from the great chief Black Partridge. Her mother was an English war bride. The Odjig family was among the Potawatomi who migrated north and settled in Wikwemikong after the War of 1812. The Potawatomi (Keepers of the Fire) were members with the Ojibwa and Odawa, of the Three Fires Confederacy of the Great Lakes. Daphne passed away at age 97 in Kelowna, BC on October 1, 2016. Art Media: Oils, Acrylics, Silkscreen Prints, Murals, Pen and Ink, Pastels, Watercolours, Coloured Pencils Recent and Upcoming Exhibitions: Daphne Odjig: Four Decades of Prints Touring exhibition of limited edition prints organized by the Kamloops Art Gallery ❖ Kamloops Art Gallery, Kamloops BC, June 8 – Aug 31, 2005 ❖ Winnipeg Art Gallery, Winnipeg MN April 22 – July 16, 2006 ❖ Canadian Museum of Civilization , Ottawa January 18 – April 20, 2008 The Drawings and Paintings of Daphne Odjig: A Retrospective Exhibition Touring exhibition organized by Art Gallery of Sudbury and National Gallery of Canada ❖ Art Gallery of Sudbury, Sudbury ON September 15 – November 11, 2007 ❖ Kamloops Art Gallery, Kamloops BC June 8 – August 31, 2008 ❖ McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinberg ON Oct. 4 , 2008 – Jan 4, 2009 ❖ Institute of American Indian Arts Museum, Santa Fe NM, June 26 – Sept. -

Witnesswitness

Title Page WitnessWitness Edited by Bonnie Devine Selected Proceedings of Witness A Symposium on the Woodland School of Painters Sudbury Ontario, October 12, 13, 14, 2007 Edited by Bonnie Devine A joint publication by the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective and Witness Book design Red Willow Designs Red Willow Designs Copyright © 2009 Aboriginal Curatorial Collective and Witness www.aboriginalcuratorialcollective.org All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. Published in conjunction with the symposium of the same title, October 12 through 15, 2007. Photographs have been provided by the owners or custodians of the works reproduced. Photographs of the event provided by Paul Gardner, Margo Little and Wanda Nanibush. For Tom Peltier, Jomin The Aboriginal Curatorial Collective and Witness gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council Cover: Red Road Rebecca Belmore October 12 2007 Image: Paul Gardner Red Willow Designs Aboriginal Curatorial Collective / Witness iii Acknowledgements This symposium would not have been possible without the tremendous effort and support of the Art Gallery of Sudbury. Celeste Scopelites championed the proposal to include a symposium as a component of the Daphne Odjig retrospective exhibition and it was her determination and vision that sustained the project through many months of preparation. Under her leadership the gallery staff provided superb administrative assistance in handling the myriad details an undertaking such as this requires. My thanks in particular to Krysta Telenko, Nancy Gareh- Coulombe, Krista Young, Mary Lou Thomson and Greg Baiden, chair of the Art Gallery of Sudbury board of directors, for their enthusiasm and support. -

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ______

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ A Knowledge and Literature Review Prepared for the Research and Evaluaon Sec@on Canada Council for the Arts _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRANCE TRÉPANIER & CHRIS CREIGHTON-KELLY December 2011 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ For more information, please contact: Research and Evaluation Section Strategic Initiatives 350 Albert Street. P.O. Box 1047 Ottawa ON Canada K1P 5V8 (613) 566‐4414 / (800) 263‐5588 ext. 4261 [email protected] Fax (613) 566‐4430 www.canadacouncil.ca Or download a copy at: http://www.canadacouncil.ca/publications_e Cette publication est aussi offerte en français Cover image: Hanna Claus, Skystrip(detail), 2006. Photographer: David Barbour Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today: A Knowledge and Literature Review ISBN 978‐0‐88837‐201‐7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS! 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY! 4 Why a Literature Review?! 4 Steps Taken! 8 Two Comments on Terminology! 9 Parlez-vous français?! 10 The Limits of this Document! 11 INTRODUCTION! 13 Describing Aboriginal Arts! 15 Aboriginal Art Practices are Unique in Canada! 16 Aboriginal Arts Process! 17 Aboriginal Art Making As a Survival Strategy! 18 Experiencing Aboriginal Arts! 19 ABORIGINAL WORLDVIEW! 20 What is Aboriginal Worldview?! 20 The Land! 22 Connectedness! -

Land & Indigenous Worldviews Norval Morrisseau

INDEPENDENT STUDENT LEARNING ACTIVITY FOR GRADES 5–12 Land & Indigenous Worldviews through the art of Norval Morrisseau REFLECT ON RELATIONSHIPS WITH THE LAND REFLECT ON RELATIONSHIPS WITH THE LAND LEARNING through the art of NORVAL MORRISSEAU TEACHER INTRODUCTION Using Norval Morrisseau’s art as a starting point, this independent activity will explore Indigenous worldviews about the land. This activity has been written to complement the Art Canada Institute online art book Norval Morrisseau: Life & Work by Carmen Robertson and adapted from the Teacher Resource Guide “Learn about Land & Indigenous Worldviews through the art of Norval Morrisseau.” For additional learning materials, please see the Art Canada Institute collection of Teacher Resource Guides. In this activity, students will analyze Morrisseau’s paintings to reflect on interdependent relationships among people, animals, plants, and the Earth. Within this activity, your students will have the opportunity to engage in critical discussion. Several platforms, such as Jamboard, Parlay, and Flipgrid, may be used to help foster rich dialogue between students throughout this activity. Students will also be given the opportunity to share their work with their peers at the end of this activity. Applications for creating a communal gallery space include CoSpaces Edu, Google Classroom, and Seesaw. Curriculum Connections Grades 5–12 Visual Arts Grades 9–12 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies ADAPTED FROM Learn about Land & Indigenous Worldviews through the art of Norval Morrisseau Grades 9 to 12 THEMES Contemporary First Nations art Indigenous activists Indigenous worldviews Land and the environment COMING 2021 INDEPENDENT STUDENT LEARNING ACTIVITY EDUCATION: Residential school and public school Morrisseau was Spirituality was the oldest of five very important to children. -

Canadian Women Artists History Initiative

IMAGINING HISTORY: THE SECOND CONFERENCE OF THE CANADIAN WOMEN ARTISTS HISTORY INITIATIVE MAY 3-5, 2012 Concordia University, Montreal Conference Program 2012 Thursday 3 May 16h00 - 16h30 Registration (outside MB S2.210) 16h30 - 18h15 Welcoming Remarks (MB S2.210) Catherine MacKenzie (Department of Art History, Concordia University) Kristina Huneault (Department of Art History, Concordia University) Keynote address Individual Lives, Collective Histories: Representing Women Artists in the Twenty- First Century Mary Sheriff, W.R. Kenan, Jr. Distinguished Professor University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 18h15 - 19h30 Reception (EV 3.741) Friday 4 May 08h30 - 16h00 Registration (EV 3.725 Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art) 09h00 - 10h30: BLOCK A STRAND ONE: METHOD Retelling Feminism I: Theory and Narrative (EV 1.605) Moderator: Susan Cahill (Nipissing University) Ordinary Affects: Folk Art, Maud Lewis and the Social Aesthetics of the Everyday, Erin Morton (University of New Brunswick) Are We There Yet? Critical Thoughts on Feminist Art History in Canada, Kristy A. Holmes (Lakehead University) Gendering the Artistic Field: The Case of Emily Carr, Andrew Nurse (Mount Allison University) STRAND TWO: HISTORY By Album, Print and Brush: Early Canadiana (EV 3.760) Moderator: Anna Hudson (York University) Louise Amélie Panet (1789-1862), Caricature and Visual Satire in Lower Canada, Dominic Hardy (L’Université du Québec à Montréal) Decoding a Victorian Woman’s Album: A Case Study in the Reading of Autobiography,