Bishop Fred Pierce Corson: a Personal Recollection Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corson Letter

Behind the Scenes: A Document Concerning the 1968 Union Editor’s Introduction by Milton Loyer, 2004 What you are about to read is such an amazing piece of United Methodist memorabilia that it merits a special introduction. In this issue of The Chronicle devoted to material to relating to the various denominational separations and unions that have resulted in the United Methodist Church, this article stands alone in its significance beyond the Central Pennsylvania Conference – not only because of its content and its authorship, but also because of its apparent rarity and the possible “disappearance” of the document to which it refers. The Central Pennsylvania Conference archives, as most other United Methodist depositories, possesses 3 versions of the Plan of Union for the proposed 1968 union between the Methodist and Evangelical United Brethren denominations. They may be described as follows. (1) A small booklet with 3 parts (historical statement, enabling legislation, constitution) prepared for the April 1964 Methodist and October 1966 EUB General Conferences. (2) A large book with 4 parts (constitution, doctrinal statements and general rules, social principals, organization and administration) prepared for the November 1966 General Conferences in Chicago. (3) A slightly modified version of #2 prepared for the 1968 Uniting Session in Dallas. Apparently there was an earlier Plan of Union version that raised a few eyebrows because among other things it proposed (as a Methodist-EUB compromise) that the episcopal appointment of district superintendents be subject to approval by the annual conference [article IX under Episcopal Supervision]. The article that follows is a November 1963 reaction paper to that Plan by Bishop Fred Pierce Corson. -

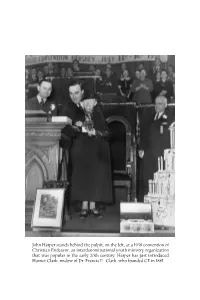

Remembering John Harper, Dr. Joe Hale

John Harper stands behind the pulpit, on the left, at a 1938 convention of Christian Endeavor, an interdenominational youth ministry organization that was popular in the early 20th century. Harper has just introduced Harriet Clark, widow of Dr. Francis E. Clark, who founded CE in 1881. Remembering John Harper Leading Layman of the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference Dr. Joe Hale Editor’s Note: For 25 years, Dr. Joe Hale served as General Secretary of the World Methodist Council. Since his retirement in 2001, he has lived in Waynesville, North Carolina. We are grateful for his willingness to contribute this article. John R. Harper was well known, not only in the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference, but across the United Methodist Church. He was active at every level of his church and denomination. A delegate to Jurisdictional and General Conferences, he also served on the General Council on Finance and Administration. He was a leader in Simpson United Methodist Church in Philadelphia, where for many years he was the church school superintendent. After moving to Langhorne, he, along with Dr. Charles Yrigoyen, Sr., organized evening worship services for the Attleboro retirement community. John was a worker and supporter of Christian Endeavor from his youth, and on one occasion was responsible for Richard Nixon addressing a large Christian Endeavor conference. In 1961, he was a member of the organizing committee for the first Billy Graham Crusade in Philadelphia. John also served as an officer of both the Sunday School Union and the YMCA. He was the first lay leader of the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference, having been elected to that role in its predecessor Philadelphia Conference in 1962, and serving until 1971. -

United Methodist Bishops Page 17 Historical Statement Page 25 Methodism in Northern Europe & Eurasia Page 37

THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA BOOK of DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2009 Copyright © 2009 The United Methodist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may reproduce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Northern Europe & Eurasia Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2009. Copyright © 2009 by The United Method- ist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. Used by permission.” Requests for quotations that exceed 1,000 words should be addressed to the Bishop’s Office, Copenhagen. Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. Name of the original edition: “The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church 2008”. Copyright © 2008 by The United Methodist Publishing House Adapted by the 2009 Northern Europe & Eurasia Central Conference in Strandby, Denmark. An asterisc (*) indicates an adaption in the paragraph or subparagraph made by the central conference. ISBN 82-8100-005-8 2 PREFACE TO THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA EDITION There is an ongoing conversation in our church internationally about the bound- aries for the adaptations of the Book of Discipline, which a central conference can make (See ¶ 543.7), and what principles it has to follow when editing the Ameri- can text (See ¶ 543.16). The Northern Europe and Eurasia Central Conference 2009 adopted the following principles. The examples show how they have been implemented in this edition. -

ELECTION DAY Tuesday, Nov

It Pays To Advertise la The Times OCEAN GROYE TIMES, TOWNSHIP OF NEPTUNE,; NEW JERSEY, FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 1963 Vol. L X X X V i n , No. u SEVEN CENTS Presents Pop Warner Award Public Hearing Dr. J. Armstrong, Cornerstone Event On Master Plan ELECTION DAY Dr. N. W. Paullin Sunday, 3:30 P.M. N EK'fUNI! — A cornerstone Planning Board To Dis Tuesday, Nov. 5th For 95th “Camp” laying service . for,' the new .$123,001) sanctuary of the 81- play Projected Growth year-old West Grove Methodist ..At Nov. 7th Meeting NEPTUNE TWP.— A tag to borrow $750 million is over; Thirteen Preachers Have NChurch will take place Sunday: heavy turnout of voters is ex- $500 million, that there is too long at 3:30 p.m..at the construction | a t i in e lag be tween the 5-y e a r pe vW Accepted Auditorium Invi site, Corlies avenue and- W al NEPTUNE TWP—A pub 'pccted here Tuesday,’as State tations To Date, Vice Presi nut street. , lic review, of the proposed '•Senator Richard R. Stout, a , 0(1 when the money is expertded to j when the proposed turnpike funds dent Truscott Reports The Rev. i)r, William R. Master Plan 'of the township Church will talte place Sunday, favorite son candidate, op .will be : released in iOTd. At; the, will be"-held next.'-Thursday poses Mayor Earl Moody of. .same time opponents feed that tHo OCEAN. GROVE— A camp- cut, will speak, and others sharing, in the servicc will lie j night, Nov. -

Editor's Preface

EDITOR'S PREFACE On behalf of the Historical Society of the Central Pennsylvania Conference of the United Methodist Church, I present volume XV of THE CHRONICLE . For fifteen years, the society has produced a mix of scholarly, entertaining, informative and inspiring stories of United Methodism connected by some theme. This volume continues that tradition with a look back at the separations and unions that define the Central Pennsylvania Conference of the United Methodist Church. The three major papers on this theme were written for college or seminary courses by United Methodist students from the Conference. They are presented in chronological order by content. Ken Loyer is a ministerial student at Duke Divinity School. His 2003 paper, Soldiers of the Lord: Francis Asbury and Freeborn Garrettson Struggle with Wesley, War and Warfare , deals with the emergence of American Methodism as a separate denomination. David Oberlin is an administrative assistant in the Mifflinburg Area School District. His 1979 paper, Two Separate Unions Formed One United Church , was written for the course in historical methods while he was a student at Lycoming College. It investigates the effect upon the local churches in Union County of the 1946 denominational union that formed the Evangelical United Brethren Church and the 1968 denominational union that formed the United Methodist Church. Edward Hunter is an undergraduate ministerial student at Lycoming College. His 2003 paper, Convergence of Identity: Two United Methodist Churches of Williamsport PA (1968-2002) , was also written for the course in historical methods. It examines what happened when neighboring Pine Street Methodist Church and First Evangelical United Brethren Church, each the flagship congregation of its own denomination in the Greater Williamsport area, became United Methodist. -

METHODIST HISTORY April 2020 Volume LVIII Number 3

METHODIST HISTORY April 2020 Volume LVIII Number 3 The Reverend Absalom Jones (1746-1818) EDITORIAL BOARD Christopher J. Anderson, Yale Divinity School Library Morris Davis, Drew University Sharon Grant, Hood Theological Seminary A. V. Huff, Furman University Russell Richey, Duke Divinity School James M. Shopshire, Sr., Wesley Theological Seminary Emeritus Ian Straker, Howard University Douglas Strong, Seattle Pacific University Robert J. Williams, Retired GCAH General Secretary Anne Streaty Wimberly, Interdenominational Theological Center Charles Yrigoyen, Jr., Wesley Theological Seminary Assistant Editors Michelle Merkel-Brunskill Christopher Rodkey Nancy E. Topolewski Book Review Editor Jane Donovan Cover: The cover image is a grayscale version of an oil on paper on board portait painted by Raphaelle Peale in 1810. See article by Anna Louise Bates (p. 133) detailing the Methodist response to the yellow fever outbreaks in Philadelphia in the 1790s. Absalom Jones and Richard Allen were key Methodist figures in organizing the African-American community to assist during this crisis. METHODIST HISTORY (ISSN 0026-1238) is published quarterly for $35.00 per year to addresses in the U.S. by the General Commission on Archives and History of The United Methodist Church (GCAH), 36 Madison Avenue, Madison, NJ 07940. Printed in the U.S.A. Back issues are available. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to METHODIST HISTORY, P.O. Box 127, Madison, NJ 07940 or email [email protected]. Methodist History, 58:3 (April 2020) “GIVE GLORY to GOD BEFORE HE CAUSE DARKNESS:” METHODISTS AND YELLOW FEVER IN PHILADELPHIA, 1793–1798 Anna Louise Bates In 1793, an outbreak of yellow fever swept through Philadelphia, the young American Republic’s capital city and foremost urban center. -

DDF Volunteers to Call at All Homes in Diocese "Stay at Home Sunday — and Open Your Church and Mission in the Diocese of Miami

THE VOICE 6180 NE Fourth Ct., Miami 37, Fla. Return Requested VOICE Weekly Publication of the Diocese of Miami Covering the 16 Counties of South Florida VOL. V, NO. 48 Price $5 a year ... 15 cents a copy FEBRUARY 14, 1964 DDF Volunteers To Call At All Homes In Diocese "Stay at home Sunday — and open your church and mission in the Diocese of Miami. door and your heart to the volunteer workers for the 1964 Diocesan Development Fund Cam- Directed to every wage-earner among the paign." more than 400,000 Catholics in the Diocese, the appeal will ask their generous support of this That isv the appeal which will be made next year's drive, for which Bishop Coleman F. Sunday, Feb. 16, from the pulpits of every Carroll has set these goals: . Construction of the Marian Center for Exceptional Methodist Bishop Wishes Children, ground for which was broken recently. Building of a Geriatrics Catholics Success In Drive Center to care for the elderly poor and to be completely equip- Exemplifying the true spirit toward achieving unity and said ped and professionally staffed to of ecumenism, an outstanding that in his opinion, perhaps in study the diseases of the aged. Methodist bishop has congratu- the distant future, reunion be- lated the Catholics of South tween Catholics and Protestants ... A home to care for teen- Florida for their generous sup- would be achieved. age boys made dependent port of the charitable projects IMPORTANT GAINS through no fault of their own, and institutions of the Diocese The Church has gone far, he to complement the new Bethany of Miami. -

The Book of Discipline

THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH “The Book Editor, the Secretary of the General Conference, the Publisher of The United Methodist Church and the Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision shall be charged with edit- ing the Book of Discipline. The editors, in the exercise of their judgment, shall have the authority to make changes in wording as may be necessary to harmonize legislation without changing its substance. The editors, in consultation with the Judicial Coun- cil, shall also have authority to delete provisions of the Book of Discipline that have been ruled unconstitutional by the Judicial Council.” — Plan of Organization and Rules of Order of the General Confer- ence, 2016 See Judicial Council Decision 96, which declares the Discipline to be a book of law. Errata can be found at Cokesbury.com, word search for Errata. L. Fitzgerald Reist Secretary of the General Conference Brian K. Milford President and Publisher Book Editor of The United Methodist Church Brian O. Sigmon Managing Editor The Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision Naomi G. Bartle, Co-chair Robert Burkhart, Co-chair Maidstone Mulenga, Secretary Melissa Drake Paul Fleck Karen Ristine Dianne Wilkinson Brian Williams Alternates: Susan Hunn Beth Rambikur THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House Nashville, Tennessee Copyright © 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may re- produce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2016. -

Together95unse.Pdf

HE riS^-S/^r ^r' * *U^1 V I «t •J&!5fc MffiW •«! I ^» ^ - I m. 1 jbai IP BHHH H^^HT Wj. T A critical review of the controversial motion picture being shown at the Protestant-Orthodox pavilion of the New York World's Fair. THE PARABLE By WILLIAM F. FORE, Executive Director, broadcasting and Tilm Commission, National Council of Churches V,ISITORS TO THE Protestant and Orthodox Cen- is that Parable, or any film, was made at all. Its acclaim ter at the New York World's Fair come away from the by Newsweek as "possibly one of the best films at the showings of an extraordinary motion picture with a fair" is an evaluation not only of the film but also of wide variety of reactions. the Protestant church. Thus, Parable, at the very least, Seen in the perspective of the fair, Parable is really proclaims that Protestantism can use a contemporarv three different things: a film, a representation of art form, and can draw a crowd with a film which asks Protestantism, and a message. relevant and thought-provoking questions. As a film, it is a unification of sound and picture Finally, Parable is a message. Here it is less success- in motion instead of the usual illustrated slide lecture ful. If a parable is "a short fictitious narrative from (with the emphasis on lecture) produced by most which a moral or spiritual truth is drawn" then this church groups. Parable is not so much a parable as a film Rorschach One of the remarkable things about Parable is that, test, in which every viewer is invited to read into it except for a brief prologue, no words are spoken. -

Of Christ Is Not an He Said He Continues to Receive Threatening Let End in Itself-Even His "Fun" Fitting Into the Ters and Insulting Telephone Calls

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Arkansas Baptist Newsmagazine Arkansas Baptist History 3-19-1964 March 19, 1964 Arkansas Baptist State Convention Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/arbaptnews Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Arkansas Baptist State Convention, "March 19, 1964" (1964). Arkansas Baptist Newsmagazine. 127. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/arbaptnews/127 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Arkansas Baptist History at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Baptist Newsmagazine by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. By Ralph A. Phelps Jr. ,. Three crosses stand on Calvary's hill Amid tumultuous shouts below. Three men die slowly on their trees In bitter anguish, sufferirut so. A robber hangs for crimes he's done And, unrepentant, makes no plea For mercy as he slowly dies, A sinner damned eternally. A second convict also dies But pleads for grace: "Remember me!" A wasted life and nothing more Than Jesus' love to set him free. A guiltless, blameless, perfect man- The third between the convicts stands. The cross of Jesus towers high And lifts the world with nail-pierced hands. Three crosses loom ,against the sky A sinner lost, a sinner saved, And one who died for sin (Praise God!) To free my soul which was enslaved. ~hoto by Louis C. · William, Page Two ARKANSAS BAPTIST Arlansa~ Bapfisi--~-'-------EniroRIALs ~ prove their point. · ' · The ministers-four )3aptists, one Nazarene .and one Methodist-went. -

Church Giving Makes Upward Strides for Ministry by Thomas Jackmon and Kent Kroehler*

Volume 7 Number 5 JUNE 07 Church giving makes upward strides for ministry By Thomas Jackmon and Kent Kroehler* In the first four months of 2007, Annual Eastern Pennsylvania Conference finances have improved signifi- Conference cantly. These monies fund mission and ministries of our United Methodist connection here in Pennsylvania and around the Pages 6 & 11 world. “The single most important element of the improvement is the record amounts our congrega- tions have given toward the appor- Making tioned funds and paid toward the billed funds,” said Mr. Moses Disciples Kumar, treasurer for the Eastern Pennsylvania Conference. “The Eastern Pennsylvania Conference Page 7 manages major funds that make ·Direct Bill has an unheard of ministry happen, both directly 33% payment rate. (Note: The Mr. Kumar added, “While we make possible our connec- through Conference agencies and total Direct Bill was reduced by celebrate that giving to all tional mission regionally, also through the ministry of ad- about 1% for 2007, due to our funds is at record levels, we nationally, and across the ministration that supports our progress in paying off the un- also acknowledge that East- world. The other five groups UM Night congregations. We celebrate these funded liability for pre-1982 ern Pennsylvania Conference seen on the chart – Pension, remarkable increases for mission, pensions.) churches have 2007 end-of- Direct Bill, Group Insurance, at the ministry, and administration.” ·Pension payments (including April arrearages totaling Property & Liability, and Work- changing to CRSP and the re- $298,509.” ers Compensation - are admin- Phillies Here is the good news: duced Direct Bill costs) have The major funds adminis- istration billings that we ·The total dollars given and increased almost 9%. -

What Happened to Wesley at Aldersgate?

What Happened To Wesley At Aldersgate? William M. Araett On May 24, 1738, "about a quarter before nine" in the evening, "^ John Wesley felt his heart "strangely warmed. It is with these simple phrases that he describes for us the event which was to transform the religious life of England and America. In the judgment of the historian Lecky, "the scene which took place at that humble meeting in Aldersgate Street forms an epoch in English history. The conviction which then flashed upon one of the most powerful and most active intellects in England is the true source of English Methodism. "2 Traditionally, Methodists have placed great stress upon Wesley's experience at Aldersgate. "For two centuries it has been described by his own followers as the hour of his conversion and, in their estimation, by far the most important day in his " ^ spiritual pilgrimage. In more recent years, however, students of Wesley have disputed about this event in Wesley's life, not only concerning the degree of its importance, but also whether or not it was the day of Wesley's conversion. We should take note of some of this controversy. EVALUATIONS OF WESLEY'S ALDERSGATE EXPERIENCE An American scholar, Umphrey Lee, asserts that the Aldersgate experience was "not an evangelical but a mystical conversion�that is, the conversion of a religious man to a 1. The Journal of John Wesley, ed. Nehemiah Curnock (London: Charles H. Kelly, n.d.), I, 475, 476. (Hereinafter re ferred to as Journal.) 2. William E. H. Lecl^,y4 History of England in the Eighteenth Century (London: Longmans Green, and Co., 1883), n,558.