Women's Participation in Endurance Motorcycle Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project PETER KOVACH Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial Interview Date: April 18, 2012 Copyright 2015 ADST Q: Today is the 18th of April, 2012. Do you know ‘Twas the 18th of April in ‘75’? KOVACH: Hardly a man is now alive that remembers that famous day and year. I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts. Q: We are talking about the ride of Paul Revere. KOVACH: I am a son of Massachusetts but the first born child of either side of my family born in the United States; and a son of Massachusetts. Q: Today again is 18 April, 2012. This is an interview with Peter Kovach. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. You go by Peter? KOVACH: Peter is fine. Q: Let s start at the beginning. When and where were you born? KOVACH: I was born in Worcester, Massachusetts three days after World War II ended, August the 18th, 1945. Q: Let s talk about on your father s side first. What do you know about the Kovaches? KOVACH: The Kovaches are a typically mixed Hapsburg family; some from Slovakia, some from Hungary, some from Austria, some from Northern Germany and probably some from what is now western Romania. Predominantly Jewish in background though not practice with some Catholic intermarriage and Muslim conversion. Q: Let s take grandfather on the Kovach side. Where did he come from? KOVACH: He was born I think in 1873 or so. -

Outlast Newsletter

Hello – With the first quarter of 2013 underway, we have many positive developments in the works to strengthen our brand positioning and continue to bring more products to market that feature the proactive benefits of our technology. We've rolled out our new brand identity that includes a refreshed logo. The new design pays respect to the strength and success of the Outlast brand as the global leader in phase change materials (PCMs) for the past 22 years, while encapsulating our relentless push for technological innovation in our field. To support this, our R&D team has introduced the world's first-ever polyester fiberfill with Outlast® technology - a development ideally suited for comforters, sleeping bags, jackets, etc. Outlast® Polyfill brings polyester fiber into the 21st century. Additionally, our partnerships continue to expand on the apparel front with a new women's boot to be introduced later this year from Papillon International. We're also working with Spanish company LS2 on new motorcycle racing helmets, as well as Ripzone™ on their line of Trilogy™ snowboarding jackets that will be lined with Outlast® technology for the 2013/2014 season. Our continued success, as always, is due in large part to our partnerships and relationships around the globe and everyone involved in our operations that contribute to expanded product offerings and applications. Warmest wishes to all of you in the New Year. Sincerely, Michael Coors CEO, Outlast Technologies Papillon International Introduces Women's Riding Boot - Fall Preview! We've partnered with Papillon International to bring to market women's riding boots for the fall 2013 season, featuring Outlast® technology in the ankle and foot lining, and the sock footbed. -

Vinyl Theory

Vinyl Theory Jeffrey R. Di Leo Copyright © 2020 by Jefrey R. Di Leo Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to publish rich media digital books simultaneously available in print, to be a peer-reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. The complete manuscript of this work was subjected to a partly closed (“single blind”) review process. For more information, please see our Peer Review Commitments and Guidelines at https://www.leverpress.org/peerreview DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11676127 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-015-4 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-016-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019954611 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Without music, life would be an error. —Friedrich Nietzsche The preservation of music in records reminds one of canned food. —Theodor W. Adorno Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments vii Preface 1 1. Late Capitalism on Vinyl 11 2. The Curve of the Needle 37 3. -

Ebook Download 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die Ebook

1001 ALBUMS YOU MUST HEAR BEFORE YOU DIE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Dimery | 960 pages | 22 Nov 2018 | Octopus Publishing Group | 9781788400800 | English | London, United Kingdom 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die PDF Book Tom Waits — Rain Dogs The band falls into the genre of chamber pop which means that the music they create is very full, with a lot of melodies and textures. Do you actually do it? Super bummed out that this album is not available on Apple Music for some strange reason. I feel like there have been sooo many of them. Elvis Costello — Armed Forces The Stooges — Raw Power Goldfrapp — Felt Mountain Talking Heads — Remain in Light These dudes soiled panties at the drop of their name. The other half i haven't even heard of. Alice Cooper — School's Out Led Zeppelin — Led Zeppelin Quicksilver Messenger Service — Happy Trails Elvis Presley — From Elvis in Memphis Impossible to put this one on and not smile. Common — Like Water for Chocolate A couple interesting things about him. Search In. The Temptations — All Directions Her Ladyship's Guide to the British Season. While musically it had an electronic sound to it, it was much more, and there was singing which was a plus. Aerosmith — Rocks Jamiroquai — Emergency on Planet Earth The B52s — The B52s John Martyn — Solid Air Flowing text. Elastica — Elastica You know, I almost included Stop Making Sense as the fourth big record of that has to be part of any topical discussion. James Brown — Live at the Apollo Bibliografische Informationen. Member Guest. Ryan Adams — Heartbreaker Metallica — Master of Puppets Reply to this topic Beastie Boys — Licensed to Ill Rush — Moving Pictures Korn's first album should be on there aswell, not only "Freak on a leash". -

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

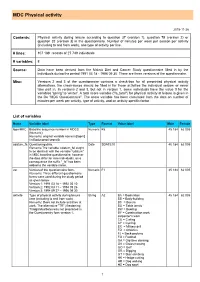

MDC Physical Activity

MDC Physical activity 2015-11-26 Contents: Physical activity during leisure according to question 37 (version 1), question 75 (version 2) or question 32 (version 3) in the questionnaire. Number of minutes per week per season per activity (including to and from work), one type of activity per line. # lines: 107 189 records of 27 749 individuals # variables: 8 Source: Data have been derived from the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study questionnaire filled in by the individuals during the period 1991 03 18 - 1996 09 30. There are three versions of the questionnaire. Misc: Versions 2 and 3 of the questionnaire contains a check-box for all preprinted physical activity alternatives, the check-boxes should be filled in for those activities the individual seldom or never take part in. In versions 2 and 3, but not in version 1, some individuals have the value 0 for the variables 'spring' to 'winter'. A total score variable ("fa_total") for physical activity at leisure is given in the file "MDC Questionnaire". The score variable has been calculated from the data on number of minutes per week per activity, type of activity, and an activity specific factor List of variables Name Variable label Type Format Value label Male Female lopnrMKC Baseline sequence number in MDCS Numeric F5 45 184 62 005 (Numeric). Remarks: original variable name is [lopnr] (in Bodycomp [seqno]). udatum_fa Questioning date. Date SDATE10 45 184 62 005 Remarks:The variable 'udatum_fa' ought to be identical with the variable "udatum" in MDC baseline questionnaire, however the date differ for nine individuals, as a consequence the suffix "_fa" has been added to the variable name. -

Writing on Your Feet

writing on your feet Reflective Practices in City as Text™ A Tribute to the Career of Bernice Braid writing on your feet Reflective Practices in City as Text™ Edited by Ada Long Series Editor | Jeffrey A. Portnoy Georgia Perimeter College National Collegiate Honors Council Monograph Series Copyright © 2014 by National Collegiate Honors Council. Manufactured in the United States National Collegiate Honors Council 100 Neihardt Residence Center University of Nebraska-Lincoln 540 N. 16th Street Lincoln, NE 68588-0627 www.ncnchonors.org Production Editors | Cliff Jefferson and Mitch Pruitt Wake Up Graphics LLC Cover and Text Design | 47 Journals LLC Cover Photos by Roy Borghouts Fotografie from the Master Class Innovators 010 Conference, Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences–Netherlands International Standard Book Number 978-0-9773623-6-3 table of contents Introduction. .ix Ada Long CHAPTER 1: History and Theory of Recursive Writing in Experiential Education . 3 Bernice Braid CHAPTER 2: Claiming a Voice through Writing. .13 John Major CHAPTER 3: The Role of Background Readings and Experts . 23 Ada Long CHAPTER 4: The Beginner’s Mind: Recursive Writing in NCHC Faculty Institutes . 33 Sara E. Quay CHAPTER 5: Assigning, Analyzing, and Assessing Recursive Writing in Honors Semesters. 41 Ann Raia CHAPTER 6: Finding Appropriate Assignments: Mapping an Honors Semester . 57 Robyn S. Martin CHAPTER 7: Adapting City as Text™ and Adopting Reflective Writing in Switzerland. 63 Michaela Ruppert Smith vii Table of Contents CHAPTER 8: Writing as Transformation. 73 1984 United Nations Honors Semester. 74 Rebekah Stone 2003 New York Honors Semester. .80 Nicholas Magilton 1981 United Nations Honors Semester. -

Motor Racing Questionnaire

Motor Racing Questionnaire Name (first, middle initial, last) Date of birth (d/m/y) Policy no. ________________ - __ Advisor’s name Advisor’s no. 1 | Automobile racing Types(s) of racing engaged in: Auto crash: २ T-bone, Rollover, Dive Bomber, etc. Kart २ Enduro, Sprint २ Demolition Derby २ Experimental, others २ Grand Touring (including Trans-Am Midget/Sprint car: २ 1/4, 1/2 and IROC) २ 3/4 Full (Outlaw) २ Record attempts २ IMSA GT Drag Racer: २ Top Fuel Dragster, Funny Car, Prostock (PRO) २ Indy Light Car २ Other or Amateur २ Vintage or other sports car racing २ Off-Road (Baja 500, Mexican 1000, etc.) Rally: २ Professional २ Stock car (Specify type) २ Other or amateur Record Attempts २ Sedan Racing (BMW, Audi, etc.) Jet Car: २ Exhibition २ Time trials २ Record attempts २ Pleasure or Income Sports Cars: २ Can-Am Professional Training २ Yes No Other _________________ २ Formula car (Specify type): Make(s), model(s) and engine size(s) of vehicles(s): _____________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________2 | Motorcycle racing Types(s) of racing engaged in: २ Drag Racer: २ Top Fuel २ Road racing (Grandprix or Productions): २ Stunt riding, acrobats, daredevils, २ Modified २ Street or stock Engine size: _____________ cc time trials or speed record attempts Make and model: _____________ _____________________________ Professional Training २ Yes २ No २ Pleasure or २ Motorcross: २ Income Engine -

Click on This Link

The Australian Songwriter Issue 108, June 2015 First published 1979 The Magazine of The Australian Songwriters Association Inc. Samantha Mooney performing at the 2014 National Songwriting Awards 1 In This Edition: Chairman’s Message Editor’s Message 2015 Australian Songwriting Contest Update Samantha Mooney: 2014 Winner of the Country Category Frank Dixon: 2014 Winner of the Youth Category ASA History: Tom Louch (1932-2009) Bob King: ASA National Songwriting Awards Photographer ASA Member Profile: Justin Standley Lola Brinton & Trish Roldan: 2014 Winners of the Australia Category ASA Member Profile: Younis Clare 2015 Queen’s Birthday Honours: Archie Roach AM Sponsors Profiles Wax Lyrical Roundup Members News and Information The Load Out Official Sponsors of the Australian Songwriting Contest About Us: o Aims of the ASA o History of the Association o Contact Us o Patron o Life Members o Directors o Regional Co-Ordinators o APRA/ASA Songwriter of the Year o Rudy Brandsma Award Winner o PPCA Live Performance Award Winner o Australian Songwriters Hall of Fame o Australian Songwriting Contest Winners 2 Chairman’s Message Dear Members, At the time of writing, we have just about come to the close of our annual National Songwriting Contest. I am licking my lips in anticipation, awaiting all the fantastic songs that will come forth. There is no doubt in my mind that each and every year brings lots of new wonderful tunes, including some that are just ‘gems’. In the meantime, your Vice Chairman and eNewslettter Editor, Alan Gilmour, has come up with another bumper issue to whet your appetite. -

Motocross Isa Team Sport...Sure Most Consider Motorcycle Racing An

Motocross IS a team sport ....Sure most consider motorcycle racing an Individual action. Yes, you can do It alone, but when we look at the big picture we clearly see there are so many elements that are Involved In the sport Many of us on the outside do not realize the behind scenes preparation The work that It takes ... From sign up to trophies .... An enormous amount of organization IS Involved April 17, 1978, a man by the name of Jerry Sharp opened a European style motocross track in Springfield, Missoun. The name of the track was Possum Hollow In dedication to their adventure In finding the ground At this time there were only three motocross tracks In the state of Mlssoun, Cycle World USA In SI. lOUIS, lake City In the Kansas City area, and Possum Hollow In Spnngfleld. For the next three years Jerry and wife, Ellie, promoted and organ- Ized motocross races at the Ozark Empire Fair Grounds and Possum Hollow It s said that Jerry was fifteen to twenty years ahead of his time In the arenacross style of racing. In 1981 Jerry started a senes that Included two tracks, Gene lewIs' lake City and his very own Possum Hollow. Tied to the GNC the events were qualifiers, at that time, for Ponca City and lake Whitney In Texas. As the years flew by Jerry continued his full time job With Gibson Greeting Cards travel- ing the states of Missoun and northern Arkansas puttmg In fifty to sixty hour weeks and still bUilding and promoting the senes. -

The University of Chicago

The University of Chicago Freak Out the Squares: The Semiotic Production of American Biker Identities and the Preservation of an Abject Sign By Cody James Boukather August 2021 A paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Master of Arts Program in the Social Sciences Faculty Advisor: Constantine Nakassis Preceptor: Victoria Gross 1 Abstract This thesis examines the political dimensions of linguistic and semiotic preservation of biker subculture as it relates to race, gender, and class among contemporary bikers in the United States. Propelled by the biker colloquialism “freak out the squares” – which is used to draw boundaries of ideological and behavioral difference between bikers and the non-biker mainstream – I investigate the embodiment of this prominent attitude within the aesthetic, material, and language practices of a subcultural group of bikers who preserve a style of choppers (custom motorcycles) that originated in the post-WW2 and countercultural eras. This style historically has influenced mainstay American biker ideologies and its authentication has become evident through the working-class cultural production of motorcycles, magazines, dress, and language that reproduce sexist, racist, and xenophobic fields of signification. While this style paints bikers as stereotypically White, male, libertarian, and violent, the current communities who preserve these cultural forms aren’t always necessarily so. Faced with this tension, I investigate the biker drive to shock and scare within the terms of what Julia Kristeva calls abjection. I use ethnographic material to discuss what role abjection holds within the sexist, racist, and xenophobic linguistic and semiotic practices of this cultural style.