Vi. Bölüm / Chapter Vi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kumpulam Makalah Tarikh Islam

Mata Kuliah: TARIKH ISLAM SEJARAH CENDIKIAWAN MUSLIM 1 CENDIKIAWAN MUSLIM 1). Al-BIRUNI (973-1048 M) Astronom berjuluk “Guru Segala Ilmu” Nama lengkap beliau adalah Abu Arrayhan Muhammad Ibnu Ahmad Al- Biruni. Dalam sumber lain di tulis Abu Raihan Muhammad Al Bairuni. Beliau lebih terkenal dengan nama Al-Biruni. Nama beliau tercatat dengan tinta emas dalam sejarah sebagai ilmuwan dan filosof Muslim yang serba bisa. Dengan penguasaan beliau terhadap pelbagai ilmu pengetahuan dan bidang lainnya, beliau mendapatkan julukan sebagai “Ustadz fil „ulum” atau guru segala ilmu dan ilmuawan modern menyebut beliau professor par exellence. Meskipun sebagian besar ilmuwan Muslim masa lalu memang memiliki kemampuan multidimensi, namun beliau tampaknya lebih menonjol. Beliau tak hanya menguasai bahasa Arab dan undang-undang islam, tapi juga Sanskrit, Greek, Ibrani dan Syiria. Beliau memiliki pengetahuan tentang filsafat Yunani, yang menjadi salah satu sebab beliau menjadi sarjana agung yang pernah dilahirkan oleh dunia Islam. Beliau berhasil membuktikan, menyandingkan ilmu dan filsafat telah memungkinkan agama bisa terus hidup subur dan berkembang serta membantu meyelesaikan permasalahan yang dihadapi oleh umat. Beliau telah menghasilkan lebih dari 150 buah buku. Di antara buku-buku itu adalah “Al-Jamahir fi Al-Jawahir” yang berbicara mengenai batu-batu permata; “Al-Athar Al-Baqiah” berkaitan kesan-kesan lama peninggalan sejarah, dan “Al-Saidalah fi Al Tibb”, tentang obat-obatan. Penulisan beliau tentang sejarah Islam telah diterjemahkan kedalam bahasa inggris dengan judul “Chronology of Ancient Nation”. Banyak lagi buku tulisan beliau diterbitkan di Eropa dan tersimpan dengan baik di Museum Escorial, Spanyol. Beliau mendirikan pusat kajian astronomi mengenai system tata surya. Kajian beliau dalam bidang sains, matematika dan geometri telah menyelesaikan banyak masalah yang tidak dapat diselesaikan sebelumnya. -

Archeologia Del Mezzo Acquatico Nel Garb Al-Andalus Porti, Arsenali, Cantieri E Imbarcazioni

Alessia Amato Archeologia del Mezzo Acquatico nel Garb al -Andalus Porti, Arsenali, Cantieri e Imbarcazioni Tese de DoutoramentoFaculdade em Letras, na de área Letrasde História Especialidade em Arqueologia, orientada pelo Doutor Vasco Gil da Cruz Mantas e apresentada ao Departamento de História, Estudos Europeus, Arqueologia e Artes da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra 2013 Archeologia del Mezzo Acquatico nel Garb al-Andalus Porti, Arsenali, Cantieri e Imbarcazioni Ficha Técnica: Tipo de trabalho Tese de Doutoramento Título Archeologia del Mezzo Acquatico nel Garb al-Andalus - Porti, Arsenali, Cantieri e Imbarcazioni- Autor/a Alessia Amato Orientador/a Prof. Doutor Vasco Gil da Cruz Mantas Identificação do Curso Doutoramento em Letras Área científica História Especialidade/Ramo Arqueologia Data 2013 Ringraziamenti / Agradecimentos Tese de doutoramento financiada pela Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO E CIÊNCIA (projecto de Bolsa Individual SFRH / BD / 45082 / 2008) A conclusione di questa Tesi di Dottorato esprimo con le seguenti parole la più profonda riconoscenza alle persone e istituzioni che con costante aiuto, in maniera decisiva, l’abbiano resa possibile, in modo che, ognuna di queste, possa fare propri i miei più sinceri ringraziamenti. Al Magnifico Rettore della Universidade de Coimbra, il Professor Dottor João Gabriel Monteiro de Carvalho e Silva, per aver veicolato i mezzi necessari all’accrescimento accademico e alla valorizzazione professionale. Alla Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO E CIÊNCIA per il finanziamento del progetto di Bolsa Individual (SFRH / BD / 45082 / 2008) e per l’appoggio all’attività di ricerca. Al Prof. Dottor Vasco Gil da Cruz Soares Mantas per aver accettato di orientare il presente lavoro, nonché i ringraziamenti per il rigore scientifico, gli ininterrotti consigli, il fermo esempio e la manifesta umanità. -

Science in the Medieval Islamic World Was the Science Developed And

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids, the Buyids in Persia, the Abbasid Caliphate and beyond, spanning the period roughly between 786 and 1258. Islamic scientific achievements encompassed a wide range of subject areas, especially astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. Medieval Islamic science had practical purposes as well as the goal of understanding. For example, astronomy was useful for determining the Qibla, the direction in which to pray, botany had practical application in agriculture, as in the works of Ibn Bassal and Ibn al-'Awwam, and geography enabled Abu Zayd al- Balkhi to make accurate maps. Islamic mathematicians such as Al- Khwarizmi, Avicenna and Jamshīd al-Kāshī made advances in algebra, trigonometry, geometry and Arabic numerals. Islamic doctors described diseases like smallpox and measles, and challenged classical Greek medical theory. Al-Biruni, Avicenna and others described the preparation of hundreds of drugs made from medicinal plants and chemical compounds. Islamic physicists such as Ibn Al-Haytham, Al-Bīrūnī and others studied optics and mechanics as well as astronomy, criticised Aristotle's view of motion. The significance of medieval Islamic science has been debated by historians. The traditionalist view holds that it lacked innovation, and was mainly important for handing on ancient knowledge to medieval Europe. The revisionist view holds that it constituted a scientific revolution. Whatever the case, science flourished across a wide area around the Mediterranean and further afield, for several centuries, in a wide range of institutions. -

Portfolio/ Bouchra Khalili | Frieze V2

INFLUENCES - 06 JUN 2016 Portfolio: Bouchra Khalili BY BOUCHRA KHALILI Roberto Rossellini, Ousmane Sembène and an inverted atlas Muhammad al-Idrisi’s world map, oriented with the South at the top, c.1154, 21 x 30 cm. Courtesy: open source; held at Bodleian Library, Oxford Muhammad al-Idrisi’s world map ‘I believe that the !rst image that counted for me, and came to be almost the ultimate image, was not an image of !lm, but an atlas of geography.’ This is a quote from the seminal French !lm critic Serge Daney, taken from Itinéraire d'un ciné-!ls (Journey of a ‘Cine-Son’, 1999). When I heard it for the !rst time, I immediately made it mine. This map of the world was drawn by Muhammad al-Idrisi. As a child, I often saw it in history books about the Islamic Golden Age, and I consider it the !rst image that really counted for me. While for decades Al-Idrisi’s Tabula Rogeriana (c.1154) was considered the most accurate atlas produced, what has always fascinated me is the beauty of these maps and the potential narratives they suggest. In this particular map, it is the Mare Internum that literally encircles the land, the strange articulation of schematic landmarks that reference the Islamic miniature tradition, and the extraordinary re!nement of the drawing and the calligraphy. It all comes together to suggest a map of a lost Atlantis. If I were using !lmic language, I would say that I see this map as less of an ancient tool of knowledge than a magni!cent syncretic combination of signs suggesting an accurate yet imaginary and poetic projection of the world. -

Examining the Swahili and Malabar Coasts During the Islamic Golden Age

TUFTS UNIVERSITY The Littoral Difference: Examining the Swahili and Malabar Coasts during the Islamic Golden Age An Honors Thesis for the Department of History Daniel Glassman 2009 2 Tabula Rogeriana, 1154 A.D. 3 Table of Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: Shared Diaspora ..................................................................................8 Islam, Commerce, and Diaspora ...............................................................................9 Reaching the Shore ..................................................................................................12 Chapter 2: The Wealth of Coasts .........................................................................20 Power of Commodities: Spices and Minerals..........................................................21 Middlemen - Home and Abroad...............................................................................25 Chapter 3: Social Charter and Coastal Politics ..................................................32 The Politics of Reciprocity.......................................................................................32 Chapter 4: Class and Caste...................................................................................40 Religion, Commerce, and Prestige ..........................................................................41 Chapter 5: Mosques and Material Culture .........................................................48 Ritual -

The Book of Roger Brady Hibbs Ouachita Baptist University

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita History Class Publications Department of History 3-31-2015 The Book of Roger Brady Hibbs Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history Part of the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Hibbs, Brady, "The Book of Roger" (2015). History Class Publications. 22. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/history/22 This Class Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Class Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brady Hibbs 31 March 2015 Medieval Europe The Book of Roger Tabula Rogeriana (Latin for “Book of Roger) is the name of a publication created by Arab cartographer Muhammad al-Idrisi in 1154 under the guidance of King Roger II of Sicily. The book is recognized for its groundbreaking world map and its accompanying descriptions and information regarding the areas shown in the map. The world map is divided into 70 regional maps, with these divisions dictated by the seven climate zones (originally proposed by Ptolemy) al-Idrisi used for the map along with ten geographical sections (Glick, 2014). The book begins with the southwestern most section, which includes the Canary Islands, to the easternmost section, then proceeds northward until each section has been represented. With each section, al-Idrisi gives textual descriptions of the land in the maps and described the people who were indigenous to those regions. The whole map includes lands from Spain in the east to China in the west, and Scandinavia in the north, down to Africa in the south. -

The Impact of Geographic Technology Through the Ages

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-6-2021 Digital Earth: The Impact of Geographic Technology Through the Ages Mishka Vance Huq CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/734 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Digital Earth: The Impact of Geographic Technology Through the Ages by Mishka Vance Huq Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geoinformatics, Hunter College The City University of New York 2021 May 6, 2021 Dr. Sean Ahearn Date Thesis Sponsor May 6, 2021 Dr. Shipeng Sun Date Second Reader Acknowledgments The author wishes to thank her advisor, Dr. Sean Ahearn, for his mentorship throughout the fulfillment of this degree as well as her thesis development and the writing process. The author also wishes to thank her second reader, Dr. Shipeng Sun, for his guidance. In addition, the author would like to acknowledge the faculty and staff of the Hunter College Department of Geography and Environmental Science, and the New York Public Library. Lastly, the author wishes to thank the Society of Women Geographers for their support and fellowship. 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

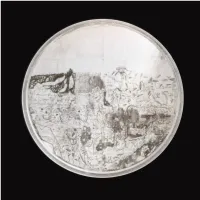

Re-Creating the Lost Silver Map of Al-Idrisi

RE-CREATING THE LOST SILVER MAP OF AL-IDRISI Entertainment for he who longs to travel the world In 1154 the Muslim scholar Al-Sharīf al-Idrīsī The silver disk is now lost, and the Entertainment compiled a geographical compendium for the survives only in the form of later manuscript copies. Norman ruler of Sicily, King Roger II, entitled the In a groundbreaking project, Factum Foundation Entertainment for He who Longs to Travel the World has teamed up with the Bodleian Library, the (Nuzhat al-mushtāq fi’khtirāq al-āfāq). The cartographic historian Professor Jerry Brotton, and Entertainment contained seventy regional maps Daniel Crouch Rare Books to re-create al-Idrisi’s of the known world, as well as a world map that fabled silver disk from an Ottoman copy of the represented the most technically sophisticated Entertainment held in the Bodleian Library, mapmaking of its time. Drawing on classical Oxford. Neither facsimile nor copy, this re-creation Graeco-Roman learning and Islamic geography, combines painstaking historical research with combined with accounts of contemporary travellers, advanced digital techniques and the highest levels Idrisi used his geographical data to make a single of craftsmanship. It pays tribute to the lost original, round map engraved onto a silver disk and set offering yet another layer to its complex and unique into a wooden table, with the Arabian peninsula history, and generating new research into one of and Mecca at its centre. the greatest of all Muslim mapmakers. Al-Idrisi and Roger ii: Mapping the world in the twelfth century A descendent of the prophet Mohammed via the King Roger was profoundly interested in ancient powerful Shi’a Idrisid dynasty, Abu Abdullah cartography. -

The Frontier Kingdom of Norman Sicily in Comparative Perspective

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- 2020 The Uniqueness of a Kingdom: The Frontier Kingdom of Norman Sicily in Comparative Perspective Onyx De La Osa University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the European History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation De La Osa, Onyx, "The Uniqueness of a Kingdom: The Frontier Kingdom of Norman Sicily in Comparative Perspective" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020-. 33. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/33 THE UNIQUENESS OF A KINGDOM: THE FRONTIER KINGDOM OF NORMAN SICILY IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE by ONYX DE LA OSA B.A. Florida Atlantic University, 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2020 © 2020 Onyx De La Osa ii ABSTRACT The frontier was once described as lands on the periphery of a culture. I argue that frontier spaces are a third space where hybridity can occur. Several of these areas existed in the medieval world with many centering around the Mediterranean and its surrounding lands. The Norman kingdom of Sicily is one such place. -

Sofala : D’Un Pôle Commercial Swahili D’Envergure Vers Un Site Archéologique Identifié ? Jules Frémeaux

Sofala : d’un pôle commercial swahili d’envergure vers un site archéologique identifié ? Jules Frémeaux To cite this version: Jules Frémeaux. Sofala : d’un pôle commercial swahili d’envergure vers un site archéologique identifié ?. Histoire. 2018. dumas-02155705 HAL Id: dumas-02155705 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02155705 Submitted on 13 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 2 نزهة المشتاق في : Illustration de couverture : Tabula Rogeriana Le Nuzhat al-mushtāq fi'khtirāq al-āfāq (arabe lit. « le livre des voyages agréables dans des pays lointains »), le plus souvent connu sous le , اختراق اﻵفاق nom Tabula Rogeriana (lit. « Le Livre de Roger » en latin) écrit par Al-Idrissi en 1154. Copie de 1929 par Konrad Miller, avec la transcription des noms en alphabet latin. 3 4 Année universitaire 2017-2018, soutenu en septembre 2018 Master Histoire médiévale de l’Afrique Institut des Mondes Africains (IMAF) / Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne 5 6 Remerciements A Mme Fazilleau pour sa disponibilité et son aide précieuse à chaque petit problème de scolarité. A ceux à qui j’ai « imposé » la relecture d’un chapitre ou d’une sous- partie dans l’inconfort du dernier moment : Claude, Lola, Pauline, Margaux, Léo… A Gérard Chouin pour m’avoir accepté trois ans de suite sur ses fouilles à Ifé, première fenêtre grande ouverte sur l’histoire d’Afrique médiévale et sur l’archéologie. -

Presented By: Supervised By

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of letters and languages Department of English THE UNIVERSAL MESSAGE OF ISLAM AND ITS CONTRIBUTION TO THE EUROPEAN CIVILIZATION Dissertation submitted as a partial fulfillment for the “Master” Degree in English Studies Presented by: Supervised by: r M Abderrahmane RAHOU Mr. Yahya ZEGHOUDI Mr Abdelkrim SENHADJI Academic year: 2014-2015 Acknowledgements Our earnest gratitude is all due to Allah the most gracious the most merciful for blessing and helping us in realizing this work. We wish to express heartfully our gratefulness to our supervisor Mr. Yahya ZEGHOUDI for his advice and valued counsel throughout all this period. Besides his ideal encouragement and guidance and most especially for his patience to fulfil this extended essay. We wish to express our deep sense of gratitude to all our teachers during our schooling years. We are fortunate in having many wonderful and good teachers whose friendly encouragement is so much appreciated. For their endless support, guidance, advice, and patience, we express our thanks to all our “Respectful Teachers” . Dedication My great thanks and heartfelt gratitude to Allah for offering me the chance to get a“Master Degree” If I write for any one the most beautiful expressions in this world, so I write them for my parents. I am so proud, privileged and honoured to dedicate the fruit of my studies and efforts to my “lovely parents” who supported me in all my endeavours. This modest work is dedicated with great respect to my Brothers and sisters. -

Le Sud-Ouest De L'océan Indien Dans Les Mappemondes

Le sud-ouest de l’océan Indien dans les mappemondes arabo-persanes d’avant le XVIe siècle : un malentendu ? Serge BOUCHET1 RÉSUMÉ L’article analyse la perception de l’espace océan Indien avant le XVIe siècle. L’étude de manuels et d’ouvrages historiques, ainsi que des sondages réalisés auprès d’un échantillon de Réunionnais mettent à jour les repré-sentations actuelles sur la connaissance de cet espace par les Arabes. Ces représentations communément admises sont confrontées aux sources géographiques arabo- persanes : il apparaît que le discours actuel est souvent réducteur et en décalage avec les données historiques. La question de la figuration de la partie sud-ouest de l’océan Indien, dans les mappemondes et dans les textes géographiques arabo-persans se révèle en effet bien plus complexe que ne le laissent entendre les simplifications énoncées comme des connaissances établies. A partir du IXe siècle, les livres de géographie arabo-persans décrivent l’océan Indien. Espace de commerce et de circulation, cet océan est traversé par les navigateurs arabes, indiens, chinois. Les ouvrages se présentent sous forme de récits de voyages ou de descriptions du monde habité, ils réunissent le savoir des populations visitées, des voyageurs et des marins. La représentation cartogra- phique des terres décrites est toutefois difficile à interpréter. Les mappemondes montrent l’océan Indien, mais le dessin de la partie sud-ouest de cet océan soulève de nombreuses questions. Ce sont ces dernières que je présenterai. Les éléments que je vais détailler sont bien connus des spé- cialistes. Mais je constate régulièrement que circulent des affirmations 1 MCF Histoire médiévale, Université de La Réunion.