Sambodhi ^ (Quarterly)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ācārya Kundakunda's

Ācārya Kundakunda’s Pravacanasāra – Essence of the Doctrine vkpk;Zizopulkj dqUndqUn fojfpr Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Ācārya Kundakunda’s Pravacanasāra – Essence of the Doctrine vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr izopulkj Ācārya Kundakunda’s Pravacanasāra – Essence of the Doctrine vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr izopulkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Charming black idol of Lord Pārśvanātha, the 7 twenty-third Tīrthańkara 1 in a Jain temple (Terāpanthī Kothī) at Shri Sammed Shikharji, y k. Jain, 20 Jharkhand, India. Pic Vija Ācārya Kundakunda’s Pravacanasāra – Essence of the Doctrine Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN: 978-81-932726-1-9 Rs. 600/- Published, in the year 2018, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) eaxy vk'khokZn & ije iwT; fl¼kUrpØorhZ 'osrfiPNkpk;Z 108 Jh fo|kuUn th eqfujkt vkxegh.kks le.kks .ksoIik.ka ija fo;k.kkfn A vfotk.karks vRFks [kosfn dEekf.k fd/ fHkD[kw AA & vkpk;Z dqUndqUn ^izopulkj* xkFkk 3&33 vFkZ & vkxeghu Je.k vkRek dks vkSj ij dks fu'p;dj ugha tkurk gS vkSj tho&vthokfn inkFkks± dks ugha tkurk gqvk eqfu leLr deks± dk {k; dSls dj ldrk gS\ vkpk;Z dqUndqUn dk ^izopulkj* okLro esa ,d cgqr gh egku xzUFk -

Moksa in Jainism -With Special Reference to Haribhadra Suri

( 14 ) Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies Vol. 54, No.3, March 2006 Moksa in Jainism -with special reference to Haribhadra Suri - Yasunori HARADA 0. Introduction In ancient India, how people could eliminate the suffering of samsara and obtain liberation (moksa) was a serious issue. This was also the case for the Jains. They developed an original theory of karma since the time of Mahavira. Umasvati (ca. 5- 6c) systematized a theory of liberation in his work, the TAAS. Within that text he describes the Jaina view of the world and karma. In the 10th chapter he explains in particular the Jaina theory of liberation. Haribhadra Suri (ca. 8c), a Jaina Svetambara monk and scholar, also discusses a theory of liberation in the 5th chapter of the Anekantavadapravesa.l)However, instead of developingUmasvati's theory of libera- tion, he criticizes the Buddhist view of momentariness (ksanikatva),in particular that of Dharmakirti (ca. 600-660AD). The present article examines the AVP, especially concerning the way in which Haribhadra Suri refutes the ksanikatva theory. In ad- dition, it compares Haribhadra Suri with his predecessor, the Digambara scholar Samantabhadra(ca. 600 AD),who takes the same view, i. e. the anekantavada. Thus this paper will shed new light on an aspect of the Jaina theory of liberation in the post-Agamic "logico-epistemological"tradition that has not as yet been studied in detail. 1. The Liberation Theory of Umasvati First, I would like to confirm the theoretical role of liberation in the TAAS. Umasvati enumerates 7 tattvas: jiva, ajiva, asrava, bandha, samvara, nirjara and moksa.2)This world, according to the TAAS, consists of jivas and ajivas. -

Dharmasvamin OCR.Pdf

BIOGRAPH'\"" OF DHARl\'lASV AMIN ( Chag lo t;,,'1-ba Chos-rje-dpal) A TIBETAN MONK PILGRIM ORIGINAL TIBETAN TEXT decipheredand translated by Dr. GEORGE ROERICH, ~M.A., Ph.D., PllOFBSIOR AND THB HE.AD Of THE DEPARTMENT OP rlULOSOPHY, INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES, THE ACADAMY OP SCIENCES, MOSCOW, IJ, S, ~. R, With a historical and critical Iutro,luction By Dr. A. S. ALTEKAR Director K. P.JAYASWAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE K. P. JAVASWAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE PATNA 11159. ] PUBl.lSIIED ON BEHALF OP THE KASH! PRASAD JA YASWAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE, PATNA DY ITS DIRECTOR, DR, A, S. ALTEKAR, M.A., Ll .. B.,D,LITT. All rights resm·ed PRINTED IN INUIA BY SIIANTILAL JAIN AT SHRI JAINENDRA l'R~:ss, JAWAHARNAOAR, DELHI, INTJIA. 1. The Government ofBihar established the K. P. Jayaswal Research Institute at Patna in 195 r with the object, inter-alia, to promote historical research, archaeological excavations and investigations and publication of works of permanent value to scholars. This Institute is one of the five others established by this Government as a token of their homage to the traditition of learning and scholarship for which ancient Bihar was noted. Apart from the J ayaswal Research Institute, five others have been established to give incentive to research and advancement of knowledge, the Nalanda Institute of Research and Post-Graduate Studies in Buddhist Learning and Pali at Nalanda, the Mithilll: Institute of Research and Post• Graduate Studies in Sanskrit Learning at Darbhanga, the Bihar Rashtra Bhasha Parishad for Research and advanced Studies in Hindi at Patna, the Institute of Post-Graduate Studies and Research in Jain and Prakrit Learning at Vaishali and the Institute of Post-Graduate Studies and Research in Arabic and Persian Leaming in Patna. -

Ten Universal Virtues

TEN UNIVERSAL VIRTUES SUPREME Munishri Ram Kumar Nandi Ten Universal Virtues Munishri Kam Kumar Nandi English Rendering by: Naresh Chandra Garg (Jain) M.A. (English & Hindi) Rtd. Vice Principal Senior-most English Lecturer J.V. Jain Inter College, Saharanpur Printed at: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29, Rajpur Road, Dehradun- 248 001 Ten Universal Virtues Munishri Kam Kumar Nandi Financiers: Shri Girnari Lal Chunni Lal Jain Chowk Fowara, Saharanpur Shri Sundar Lal Ramesh Chandra Jain Shaheed Ganj, Saharanpur Cost Price: Rs. 45/- Price for Mundane Souls: Utility First Edition: 1994, 1000 copies [c] All rights reserved Available at: Shri Vinod Jain V.K.J. Builders and Contractors (Pvt.) Ltd. 162/3/1, Rajpur Road, Dehradun 248 001 Tel: (0135) 623540, 28035 Shri Vivek Jain 229/1 Krishnapuri, Muzaffarnagar - 251 002 (U.P.) Tel: (0131) 26762 Typesetting and Printing at: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29, Rajpur Road, Dehradun -248 001 Tel: (0135) 28971 MUNISHRI 108 KAM KUMAR NANDI Monkshood Name Muni Kam Kumar Nandi Birth Place Village Khawat Kappa, Distt. Belgaum (Karnataka) Father’s Name Late Shri Bhimappa Mother’s Name Shrimati Ratnva Brothers Four brothers Sisters Three sisters Real Name Shri Bhramappa (fourth child of the family) Date of birth 6th June, 1967 Renunciation year November, 1988 Place of Celibacy Vow Ankloose (Maharastra) Celibacy Vow & Gandhar Acharya Shri Kunthu Sagarji Initiation ceremony by Place of Initiation Ceremony Holy mount Shri Sammed Shikher ji Teachers of Jain thought 1. Acharya Shri Vidhya Nand ji 2. Upadhaya Shri Kanak Nand ji Study of Languages Kannad, Hindi, English, Sanskrit, Prakrit, Marathi and Brahami script Daily Routine Constant meditation, incessant study (reading, writing, learning of sacred books), delivering sermons and religious discourse Up-to-date Chaturmas Under the supervision of Gandhar (Four-month rainy season Acharya Shri Kunthu Sagarji at Aara stay) (Bihar), Baraut (U.P.), Muzaffarnagar (U.P.), Rohtak Haryana) Under the supervision of Acarya Vidya Nand ji at Kundkund Bharati, New Delhi. -

Total No. of Diesel Vehicles Registered in ROHINI

Total No. of Diesel Vehicles is registered before 07-nov-2001 or 15 years old and not have valid fitness on 08-nov-2016 Sno regn_no regn_dt fit_upto owner_name f_name p_add1 p_add2 p_add3 p_pincodedescr off_name 76028 DNH5736 10-11-1989 09-11-2004 MADHU SHARMA & VARINDER KUMAR 73-A KHANNA MARKET TIS HAZARI DELHI 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76029 DL8C7087 24-08-1994 23-08-2009 SUBODH SINGH SUGRIV SINGH A-30 EAST UTTAM NGR DELHI 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76030 DL8CB8642 09-04-1997 08-04-2012 PRITHVI RAJ SH PYARE LAL 228 VILL SAMAI PUR DELHI-42 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76031 DL8CB4169 19-06-1996 18-06-2011 DINESH RANBIR SINGH N 8 SATYAWATI COLY ASHOK VIHAR DELHI 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76032 DNH2099 15-09-1989 14-09-2004 THE TRESURER AICC (I) NA 24 AKBAR ROAD NEW DE LHI 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76033 DNH4334 23-10-1989 22-10-2004 MANJU CHAUHAN W/O SATPAL CHAUHAN 2175/114 H NO 118 PANCHSHEEL VIHAR KHIRKI EXTN.N DELHI 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76034 DL8C4418 15-04-1994 14-04-2009 RAMA KANT S/O MAUJI RAM L-159 J J COLONY AM SHAKARPUR DELHI 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76035 DL8CB7350 06-12-1996 05-12-2011 SUKDEEP SINGH BHAGWANT SINGH 8 POOSA ROAD DELHI 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76036 DL8CB7351 06-12-1996 05-12-2011 PREM WATI JILE SINGH TIKRI KALAN DELHI 45 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76037 DNH2582 27-09-1989 26-09-2004 SH RAJEEV BABEL S/O SH D C BABEL C-29 N D S E PART-I AMRIT NAGAR N DELHI 110049 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76038 DL8C8385 19-02-1996 18-02-2011 NA NA NA 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76039 DL8CB8009 04-02-1997 03-02-2012 MD ASIF NAIM JEHRA H N 98 KHUREJI KHAS DL 51 0 DIESEL ROHINI 76040 DL8CG4870 02-07-2001 01-07-2016 SOMESHWAR SINGH SH HEM PAL SINGH C-II/48 NEW ASHOK NAGAR DELHI . -

Notes on Modern Jainism

'J UN11 JUI .UBRARYQr c? IEUNIVER%. fHONVSOV | I ! 1 I i r^ 5, 3 ? \E-UNIVER. <~> **- 1 S 'OUJMVJ'iU ' il g i i i I s fc i<^ vvlOS-ANCELfX^ " - ^ <tx-N__^ # = =3 1( ^ Af-UNIVfl% il I fe ^'^ t $ ^ ^*-~- ^ ^ NOTES ON MODERN JAINISM WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE S'VETA'MBARA, DIGAMBARA AND STHA'NAKAVA'SI SECTS. BY MRS. SINCLAIR STEVENSON, M.A. (T.C.D.) SOMETIME SCHOLAR OF SOMERVILLE COLLEGE, OXFORD. OXFORD S i B. H. BLACKWELL, 50 & 51 BROAD REET LONDON SIMPKIN, MARSHALL & Co, LIMITED SURAT : IRISH MISSION PRESS 1910. Stack Annfv r 333 HVNC LIBELLVM DE TRISTS VITAE SEVERITATE CVM MEAE TVM MARITI MATR! MEMORiAE MONVMENTVM DEDICO QVAE EXEMPLVM LONGE ALIVM SECVTAE NOMEN MATERNVM TAM FELICITER ORNAVERVNT. ** 2029268 PREFACE. THESE notes on Jain ism have been compiled mainly from information supplied to me by Gujarati speaking Jaina, so it has seemed advisable to use the Gujarati forms of their technical terms. It would be impossible to issue this little book without expressing my indebtedness to the Rev. G. P. Taylor, D. D., Principal of the Fleming Stevenson Divinity College, Ahmedabad, who placed all the resources of his valuable library at my disposal, and also to the various Jaina friends who so courteously bore with my interminable questionings. I am specially grateful to a learned Jaina gentleman who read through all the MS. with me, and thereby saved me, I hope, from some of the numerous pitfalls which beset the pathway of anyone who ventures to explore an alien faith. MARGARET STEVENSON. Irish Mission, Rajkot. India. -

The Heart of Jainism

;c\j -co THE RELIGIOUS QUEST OF INDIA EDITED BY J. N. FARQUHAR, MA. LITERARY SECRETARY, NATIONAL COUNCIL OF YOUNG MEN S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS, INDIA AND CEYLON AND H. D. GRISWOLD, MA., PH.D. SECRETARY OF THE COUNCIL OF THE AMERICAN PRESBYTERIAN MISSIONS IN INDIA si 7 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME ALREADY PUBLISHED INDIAN THEISM, FROM By NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., THE VEDIC TO THE D.Litt. Pp.xvi + 292. Price MUHAMMADAN 6s. net. PERIOD. IN PREPARATION THE RELIGIOUS LITERA By J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A. TURE OF INDIA. THE RELIGION OF THE By H. D. GRISWOLD, M.A., RIGVEDA. PH.D. THE VEDANTA By A. G. HOGG, M.A., Chris tian College, Madras. HINDU ETHICS By JOHN MCKENZIE, M.A., Wilson College, Bombay. BUDDHISM By K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. ISLAM IN INDIA By H. A. WALTER, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. JAN 9 1986 EDITORIAL PREFACE THE writers of this series of volumes on the variant forms of religious life in India are governed in their work by two impelling motives. I. They endeavour to work in the sincere and sympathetic spirit of science. They desire to understand the perplexingly involved developments of thought and life in India and dis passionately to estimate their value. They recognize the futility of any such attempt to understand and evaluate, unless it is grounded in a thorough historical study of the phenomena investigated. In recognizing this fact they do no more than share what is common ground among all modern students of religion of any repute. -

Jain Tattvas and Philosophy of Karma - by Pravin K

Read part 1 here Jain Tattvas and Philosophy of Karma - By Pravin K. Shah Asrava (Cause of the influx of karma) Asrava is the cause, which leads to the influx of good and evil karma which leads to the bondage of the soul. Asrava may be described as an attraction in the soul toward sense objects. The following are causes of Asrava or influx of good and evil karma: Mithyatva - Ignorance Avirati - Lack of self-restraint Pramada* - Unawareness or unmindfulness Kasaya - Passions like anger, conceit, deceit, and lust Yoga - Activities of mind, speech, and body *Some Jain literature mention only four causes of Asrava. They include Pramad in the category of Kasaya. Bandha (Bondage of karma) Bandha is the attachment of karmic matter (karma pudgala) to the soul. The soul has had this karmic matter bondage from eternity because of its own ignorance. This karmic body is known as the karmana body or causal body or karma. The karmic matter is a particular type of matter which is attracted to the soul because of soul's ignorance, lack of self-restraint, passions, unmindfulness, activities of body, mind, and speech. The soul, which is covered by karmic matter, continues acquiring new karma from the universe and exhausting old karma into the universe through the above-mentioned actions at every moment. Because of this continual process of acquiring and exhausting karma particles, the soul has to pass through the cycles of births and deaths and experiencing pleasure and pain. So under normal circumstances, the soul can not attain freedom from karma and hence liberation. -

An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide

AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 1 2Prakrit Bharati academy,An Ahimsa Crisis: Jai YouP Decideur Prakrit Bharati Pushpa - 356 AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 3 Publisher: * D.R. Mehta Founder & Chief Patron Prakrit Bharati Academy, 13-A, Main Malviya Nagar, Jaipur - 302017 Phone: 0141 - 2524827, 2520230 E-mail : [email protected] * First Edition 2016 * ISBN No. 978-93-81571-62-0 * © Author * Price : 700/- 10 $ * Computerisation: Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur * Printed at: Sankhla Printers Vinayak Shikhar Shivbadi Road, Bikaner 334003 An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 4by Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide Contents Dedication 11 Publishers Note 12 Preface 14 Acknowledgement 18 About the Author 19 Apologies 22 I am honored 23 Foreword by Glenn D. Paige 24 Foreword by Gary Francione 26 Foreword by Philip Clayton 37 Meanings of Some Hindi & Prakrit Words Used Here 42 Why this book? 45 An overview of ahimsa 54 Jainism: a living tradition 55 The connection between ahimsa and Jainism 58 What differentiates a Jain from a non-Jain? 60 Four stages of karmas 62 History of ahimsa 69 The basis of ahimsa in Jainism 73 The two types of ahimsa 76 The three ways to commit himsa 77 The classifications of himsa 80 The intensity, degrees, and level of inflow of karmas due 82 to himsa The broad landscape of himsa 86 The minimum Jain code of conduct 90 Traits of an ahimsak 90 The net benefits of observing ahimsa 91 Who am I? 91 Jain scriptures on ahimsa 91 Jain prayers and thoughts 93 -

SL Patient Name SRF ID Final Result 1 MANOJ ORAON 2033900051210 Negative 2 ANSU GOSWAMI 2033900051213 Negative 3 ROBERT SORENG 2

SL Patient Name SRF ID Final Result 1 MANOJ ORAON 2033900051210 Negative 2 ANSU GOSWAMI 2033900051213 Negative 3 ROBERT SORENG 2033900051288 Negative 4 EMANUOL TIGGA 2033900051214 Negative 5 BINOD KUMAR BHAGAT 2033900051215 Negative 6 MAHI TOPPO 2033900051216 Negative 7 MD SHARIB 2033900051275 Negative 8 JYOTI DEVI 2033900051217 Negative 9 AMIT KUMAR 2033900051218 Negative 10 NANTU RAJAK 2033900051276 Negative 11 YASH KUMAR 2033900051277 Negative 12 NIRMAL CHAND MAHATO 2033900051219 Negative 13 SUNIL KUMAR SINGH 2033900051278 Negative 14 PREETI MUNDA 2033900051220 Negative 15 SAYAD KALIM UDDIN 2033900051279 Negative 16 PANKAJ KUMAR 2033900051221 Negative 17 RAM PUKAR YADAV 2033900051222 Negative 18 RUPAL NAYAK 2033900051281 Negative 19 SATYA KUMARI MINJ 2033900051223 Negative 20 SANDEEP TIWARI 2033900051282 Negative 21 SHASHI KANT SINGH 2033900051283 Negative 22 KHUSHI RANI 2033900051285 Negative 23 ALOK BISWAS 2033900051286 Negative 24 PUNAM KUMARI 2033900051287 Negative 25 MANISHA KHALKHO 2033900051291 Negative 26 PREM KHALKHO 2033900051293 Negative 27 SHAKUNTALA DEVI 2033900051295 Negative 28 BINOD SINGH MUNDA 2033900051297 Negative 29 SOBINA ANJU KUJUR 2033900051298 Negative 30 KENAL MARANDI 2033900051300 Negative 31 BALDEV SURIN 2033900051301 Negative 32 NAUNIN PARWEEN 2033900051224 Negative 33 SHUBHAM KUMAR 2033900051303 Negative 34 JINNAT PARWEEN 2033900051226 Negative 35 SALAMAT ANSARI 2033900051304 Negative 36 ANNIE ROBA 2033900051227 Negative 37 VIJAY EKKA 2033900051306 Negative 38 NIKITA MANJHI 2033900051228 Negative 39 TELESPORE -

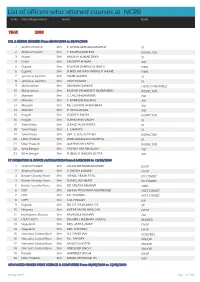

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Comparative Analysis of the Philosophies of Enlightenment

ENLIGHTENMENTS: Towards a Comparative Analysis of the Philosophies of Enlightenment in Buddhist, Eastern and Western Thought and the Search for a Holistic Enlightenment Suitable for the Contemporary World © Thomas Clough Daffern (B.A. Hons D.Sc. Hon PGCE), Director, International Institute of Peace Studies and Global Philosophy SOAS Buddhist Conference for Dongguk University on Global Ecological problems and the Buddhist Perspective, Feb. 2005 INDEX 1. Enlightenments: why the plural ? Some introductory questions 2. European Classical enlightenments 3. Zoroastrian Enlightenments 4. Enlightenments in Judaism 5. Christian enlightenments 6. Islamic Enlightenments 7. Buddhist Enlightenments 8. Hindu Enlightenments 9. Chinese enlightenments 10. Shinto 11. Pagan and Neo-pagan enlightenments 12. Transpersonal enlightenment theory 13. Conclusions 1. Enlightenments: why the plural ? Some introductory questions A word first about the basic presuppositions underlying this paper. I wish to institute a semantic and linguistic reform into our discussion abut enlightenment both in the academic literature and in everyday speech. We are all used to talk of the nature of enlightenment; Buddhist and Hindu textbooks carry information on the nature of enlightenment, as do Western philosophical and historical texts, although here we more often talk of The Enlightenment, as a period of largely European originated intellectual history, running from approximately the 1680’s to an indeterminate time, but usually September 1914 is taken as cut off time. This paper