History and Disposition of the U-85 by Joe Hoyt Introduction the U-85 Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’S War Against Caribbean Oil

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’s War Against Caribbean Oil Bercuson, David J.; Herwig, Holger H. University of Calgary Press Bercuson, D. J. & Herwig, H. H. "Long Night of the Tankers: Hitler’s War Against Caribbean Oil". Beyond Boundaries: Canadian Defence and Strategic Studies Series; 4. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49998 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com LONG NIGHT OF THE TANKERS: HITLER’S WAR AGAINST CARIBBEAN OIL David J. Bercuson and Holger H. Herwig ISBN 978-1-55238-760-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

U.S. Gato Class 26 Submarine Us Navy Measure 32/355-B

KIT 0384 85038410200 GENERAL HULL PAINT GUIDE U.S. GATO CLASS 26 SUBMARINE US NAVY MEASURE 32/355-B In the first few months immediately following the Japanese attack on surface and nine knots under water. Their primary armament consisted Pearl Harbor, it was the U. S. Navy’s submarine force that began unlimited of twenty-four 21-inch torpedoes which could be fired from six tubes in the warfare against Japan. While the surfaces forces regrouped, the submarines bow and four in the stern. Most GATO class submarines typically carried began attacking Japanese shipping across the Pacific. Throughout the war, one 3-inch, one 4-inch, or one 5-inch deck gun. To defend against aircraft American submarines sunk the warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy and while on the surface, one or two 40-mm guns were usually fitted, and cut the lifeline of merchant vessels that provided Japan with oil and other these were supplemented by 20mm cannon as well as .50 caliber and vital raw materials. They also performed other important missions like staging .30 caliber machine guns. Gato class subs were 311'9" long, displaced commando raids and rescuing downed pilots. The most successful of the 2,415 tons while submerged, and carried a crew of eighty-five men. U. S. fleet submarines during World War II were those of the GATO class. Your hightly detailed Revell 1/72nd scale kit can be used to build one of Designed to roam the large expanses of the Pacific Ocean, these submarines four different WWII GATO class submarines: USS COBIA, SS-245, USS were powered by two Diesel engines, generating 5,400 horse power for GROWLER, SS-215, USS SILVERSIDES, SS-236, and the USS FLASHER, operating on the surface, and batteries provided power while submerged. -

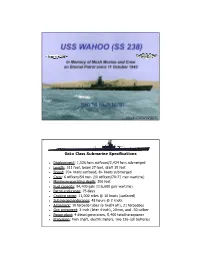

Gato Class Submarine Specifications

1 Prepared by a former Mare Island yardbird, in memory of those who have gone before him 2 Gat o Class Submarine Specificat ions z Displace ment: 1,526 tons surfaced/2,424 tons submerged z Length: 311 feet, beam 27 feet, draft 15 feet z Speed: 20+ knots surfaced, 8+ knots submerged z Crew: 6 officers/54 men (10 officers/70-71 men wartime) z Maximum operating depth: 300 feet z Fuel capacity: 94,400 gals (116,000 gals wartime) z Patrol endurance: 75 days z Cruising range: 11,000 miles @ 10 knots (surfaced) z Submerged endurance: 48 hours @ 2 knots z A rma me nt : 10 torpedo tubes (6 fwd/4 aft), 21 torpedoes z Gun armament: 3-inch (later 4-inch), 20mm, and .50 caliber z Power plant: 4 diesel generators, 5,400 total horsepower z Propulsion: twin shaft, electric motors, two 126-cell batteries 3 Gato Class Internal Arrangement 4 Combat History of USS Wahoo z Seven war patrols z Credited with sinking 27 ships totaling over 125,000 tons z Earned 6 battle stars and awarded a Presidential Unit Citation z Commanded by CDR Dudley W. “Mush” Morton on last five patrols z One of 52 U.S. submar ines lost in WWII z Wahoo and other U.S. submarines completed 1,560 war patrols and sank over 5.6 million tons of Japanese shipping Wahoo patch & battle flag 5 Keel Laying - 28 June 1941 6 Wahoo Pressure Hull Sect ions - 1941 7 Under Construction on Building Way - January 1942 8 Launching Day - 14 February 1942 9 Launching Sponsor - Mrs. -

Gato Class Boats Finished the War with a Mod 3A Fairwater

A VISUAL GUIDE TO THE U.S. FLEET SUBMARINES PART ONE: GATO CLASS (WITH A TAMBOR/GAR CLASS POSTSCRIPT) 1941-1945 (3rd Edition, 2019) BY DAVID L. JOHNSTON © 2019 The Gato class submarines of the United States Navy in World War II proved to be the leading weapon in the strategic war against the Japanese merchant marine and were also a solid leg of the triad that included their surface and air brethren in the USN’s tactical efforts to destroy the Imperial Japanese Navy. Because of this they have achieved iconic status in the minds of historians. Ironically though, the advancing years since the war, the changing generations, and fading memories of the men that sailed them have led to a situation where photographs, an essential part of understanding history, have gone misidentified which in some cases have led historians to make egregious errors in their texts. A cursory review of photographs of the U.S. fleet submarines of World War II often leaves you with the impression that the boats were nearly identical in appearance. Indeed, the fleet boats from the Porpoise class all the way to the late war Tench class were all similar enough in appearance that it is easy to see how this impression is justified. However, a more detailed examination of the boats will reveal a bewildering array of differences, some of them quite distinct, that allows the separation of the boats into their respective classes. Ironically, the rapidly changing configuration of the boats’ appearances often makes it difficult to get down to a specific boat identification. -

National Register Off Historic Places Inventory

NPS Form 10-900 War in the Pacific Ship Study OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Federal Agency Nomination Exp. 10-31-64 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS UM only National Register off Historic Places received Inventory — Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries — complete applicable sections 1. Name historic USS Cod (SS-224) and or common 2. Location street & number North Marginal Drive —— not for publication city, town Cleveland __ vicinity of 035 state Ohio code 39 county Cuyahoga code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use __ district __ public _X. occupied __ agriculture X museum __ building(s) _X- private __ unoccupied __ commercial __park __ structure __ both __ work in progress z_ educational —— private residence __ site Public Acquisition Accessible __ entertainment __ religious JL_ object __ in process —— yes: restricted __ government __ scientific __ being considered __ yes: unrestricted __ industrial __ transportation __ no __ military —— other: 4. Owner off Property name Cleveland Coordinating Committee for Cod, Inc. street & number 1089 East 9th Street city, town Cleveland __ vicinity of state Ohio 44114 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Department of the Navy street & number Naval Sea Systems Command city, town Washington 8tate DC 20362 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title None has this property been determined eligible? __ yes no date federal state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one __ excellent -_ deteriorated -X unaltered N/Aoriginal site X good __ ruins __ altered ._ moved date __ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance USS Cod (SS-224) was built by the Electric Boat Company of Groton, Connecticut. -

Rov Investigations of the Dkm U-166 Shipwreck Site to Document the Archaeological and Biological Aspects of the Wreck Site

ROV INVESTIGATIONS OF THE DKM U-166 SHIPWRECK SITE TO DOCUMENT THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND BIOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF THE WRECK SITE FINAL PERFORMANCE REPORT NOAA AWARD NO. NA03OAR4600103 Prepared for the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration By 730 East Kaliste Saloom Road Lafayette, LA 70508 October 2004 Daniel J. Warren Marine Archaeologist/Principle Investigator 730 E. KALISTE SALOOM RD LAFAYETTE, LA 70508 AUTHOR PAGE Daniel Warren Principle Investigator/Marine Archaeologist C & C Technologies, Inc. Robert Church Co-Principle Investigator/Marine Archaeologist C & C Technologies, Inc. Dr. Roy Cullimore Co-Principle Investigator/Senior Microbiologist Droycon Bioconcepts, Inc. Lori Johnston Field Microbiologist Droycon Bioconcepts, Inc. 730 E. KALISTE SALOOM RD LAFAYETTE, LA 70508 Author's Note The DKM U-166 and the S.S. Robert E. Lee are recognized war graves and irreplaceable pieces of the world's maritime heritage. Therefore, all coordinates and block numbers have been excluded from this report in an effort to protect the integrity of the wreck sites. 730 E. KALISTE SALOOM RD LAFAYETTE, LA 70508 ABSTRACT In October 2003, investigations were undertaken by C & C Technologies Inc., in conjunction with the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration, Droycon Bioconcepts, Inc. and the PAST Foundation, to document the wreck site of the DKM U-166 in 5,000 feet of water in the Mississippi Canyon Area of the Gulf of Mexico. At the time, the project was the deepest archaeological investigation ever conducted in the Gulf of Mexico. This project marked one of the first instances that positioning technology that is routinely used in the offshore oil and gas industry was utilized on a deepwater archaeological investigation of a shipwreck. -

World War II Shipwrecks and Submarine Attacks in NSW Waters

detonated against the boat’s side. The steel screw steamer weighed 287 tons and was 39.6 metres long. These incidents confirmed that Axis vessels were laying minefields around the Australian coast. German commerce raiders including WORLD WAR TWO Pinguin, Orion and Passat (ex-Storstad) laid a succession of minefields off New South Wales, SHIPWRECKS AND Tasmania, Victioria, South and Western SUBMARINE ATTACKS Australia. These are credited with also claiming the IN NSW WATERS steamers’ Cambridge and City of Rayville off 1940-1944 the Victorian coast from November 1940, and damage to the Hertford off South Australia in December. The raider Kormoran famously sank Information Sheet - Heritage Branch the cruiser HMAS Sydney off Western Australia on 19 November 1941. German raiders had been active in NSW waters during the First World War with the raider Wolf laying a minefield off Gabo Island that claimed the British freighter Cumberland in 1917. That wreck site has been located. IJN submarine I-15, namesake of the B-1 class of long range scouting submarines. I-21, I-27 and I-29 were of this 1942: Start of the Australian east type. Image courtesy: Stille, 2007. coast submarine offensive Introduction Wartime secrecy meant that the public knew During 1942, Japanese submarines I-11, I-21, I little of the impact on merchant vessels by 22, I-24, I-27, I-29, and I-175 conducted enemy submarines during WWII. But Japanese operations in NSW’s waters. The submarines submarines, even a German U-boat and to a accountered for nine (9) vessels sunk and four lesser extent minelayers, had significant (4) damaged. -

HR.10240 Nvg118covuk

OSPREY New Vanguard PUBLISHING US Submarines 1941–45 Jim Christley • Illustrated by Tony Bryan © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com New Vanguard • 118 US Submarines 1941–45 Jim Christley • Illustrated by Tony Bryan © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US SUBMARINES 1941–45 INTRODUCTION he shooting portion of World War II burst on the American Navy early on a Sunday morning in December 1941, with the Japanese Tattack on Pearl Harbor. On that morning the face of naval warfare in the Pacific changed utterly. No longer would the war at sea be decided by squadrons of the world’s largest and most powerful battleships. Instead, the strategic emphasis shifted to a combination of two more lethal and far-ranging naval weapon systems. The aircraft carrier would replace the battleship by being able to increase the deadly range of a fleet from a few tens of miles – the range of battleship guns – to the hundreds of miles range of bomb- and torpedo-carrying aircraft. In addition, the American submarine would be able to place a strangler’s grip on the throat of the Japanese empire that, unlike the German U-boats’ attempts to control the Atlantic waters, could not be broken. Some have said that the result of the attack at Pearl Harbor was fortuitous in that it forced the US Navy to look toward the carrier and submarine to defend the southern Pacific and the United States’ western coast. This argument overlooks, however, the prewar build-up in those two weapons platforms, which seems to indicate that some individuals were looking seriously toward the future and the inevitable conflict. -

The German Torpedo Crisis in World War Two

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2010 Wolves Without Teeth: The German Torpedo Crisis in World War Two David Habersham Wright Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Wright, David Habersham, "Wolves Without Teeth: The German Torpedo Crisis in World War Two" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 599. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/599 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOLVES WITHOUT TEETH: THE GERMAN TORPEDO CRISIS IN WORLD WAR TWO by David Habersham Wright (Under the Direction of Charles Thomas) Abstract The “Torpedo Crisis,” or “Torpedokrise” as referred to by the Germans, is the name given to the period of the first few years during the Second World War during which time the German U-boat arm experienced catastrophic technical malfunctions with their torpedoes. These malfunctions robbed the Germans of tremendous success during the most critical period of the Second World War – the opening years during which Allied anti-submarine measures were at their poorest and German prospects for success concomitantly at their greatest. By the time the Germans finally succeeded in removing all of these problems and realized the true potential of the torpedo envisioned during the prewar years, Allied anti- submarine warfare tactics and especially technology had advanced to such a degree that it could not be overcome despite the best efforts of the U-bootwaffe. -

FORT MILES in WORLD WAR II: the GERMAN U-BOAT THREAT by James D

This is the first in a series of articles about Fort Miles to be posted on the FMHA website. Future articles, posted quarterly, will include subjects such as the sinking of USS Jacob Jones (DD- 130), Fort Miles antisubmarine defenses, the guns of Fort Miles, the establishment of Fort Miles, the sinking of SS John R. Williams, and the U.S. Navy at Fort Miles, among others. Winter 2021 FORT MILES IN WORLD WAR II: THE GERMAN U-BOAT THREAT By James D. Shomper Although Fort Miles never had to fire a shot in combat during World War II, the Battle of the Atlantic was fought not far from its shores. The war was much closer to the U.S. east coast than many realize today. PRELUDE TO WAR At the outset of the war, the U.S. military believed the greatest threat to the Delaware Bay and coast was an attack by an enemy surface fleet. The German Navy (“Kriegsmarine”) had some of the most modern, powerful battleships in the world at the time. America’s industrial might was essential to stopping Nazi Germany in Europe and the Japanese Empire in the Pacific. American industries critical to the war effort such as oil refineries, chemical production and shipbuilding lined the Delaware Bay and River up to Wilmington and Philadelphia. A German attack on the Delaware Bay led by their battleships would strike a severe blow to U.S. industrial production and the delivery of vital war supplies to the U.S. military and our allies in Europe, most notably England and Russia, who were the last impediment to Nazi domination. -

A Visual Guide to the U.S

A VISUAL GUIDE TO THE U.S. FLEET SUBMARINES PART TWO: SALMON & SARGO CLASSES 1936-1945 BY DAVID L. JOHNSTON 2010 As the decade of the 1930’s moved into its second half, submarine development in the United States Navy was rolling along at a brisk pace. The fits and starts of concept development and the limitations of an as yet under-developed technological base had been largely overcome by 1936. The Salmon and Sargo classes ultimately proved to be a solid step in the developmental ladder that led to the war winning Gato, Balao, and Tench class submarines. Although technological experimentation was still underway in many areas, the design process was maturing rapidly and the Navy and its contractors were learning with each succeeding boat. The sixteen submarines of the Salmon group all have the same performance specifications and the same armament, and all of their names started with the letter S. As far as the Navy is concerned, all sixteen boats belong to the same class. However, they are actually made up of no less than five distinct groups, each with unique characteristics that separate them from the others. It must be remembered that at this point in USN submarine development (1936-38), designers were still tinkering with the fleet boat concept, trying to find the right combination of factors to optimize its performance. The civilian Electric Boat Company (EB) was particularly keen on maintaining its own in-house design capability separate from the government’s (based at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard) and thus numerous detail differences crept into their plans. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: U-85 (shipwreck and remains) Other names/site number: ____________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ____ World War II Shipwrecks along the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico__________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: _Offshore____________________________________________ City or town: Offshore-Nags Head State: Offshore-NC County: Offshore-Dare___ Not For Publication: Vicinity: x ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the