Comets with Poisonous Tails, Risk Narratives and Comments Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS V6 with Figures

Grism Spectroscopy of Comet Lulin Swift UVOT Grism Spectroscopy of Comets: A First Application to C/2007 N3 (Lulin) D. Bodewits1,2, G. L. Villanueva2,3, M. J. Mumma2, W. B. Landsman4, J. A. Carter5, and A. M. Read5 Submitted to the Astronomical Journal on 16th February, 2010 Revised version October 21st, 2010 1 NASA Postdoctoral Fellow, [email protected] 2 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Solar System Exploration Division, Mailstop 690.3, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 3 Dept. of Physics, Catholic University of America, Washington DC 20064, USA 4 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Astrophysics Science Division, Mailstop 667, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 5 Dept. of Physics and Astronomy, Leicester University, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK 8 figures, 4 tables Key words: Comets: Individual (C/2007 N3 (Lulin)) – Methods: Data Analysis – Techniques: Image Spectroscopy – Ultraviolet: planetary systems Abstract We observed comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin) twice on UT 28 January 2009, using the UV grism of the Ultraviolet and Optical Telescope (UVOT) on board the Swift Gamma Ray Burst space observatory. Grism spectroscopy provides spatially resolved spectroscopy over large apertures for faint objects. We developed a novel methodology to analyze grism observations of comets, and applied a Haser comet model to extract production rates of OH, CS, NH, CN, C3, C2, and dust. The water production rates retrieved from two visits on this date were 6.7 ± 0.7 and 7.9 ± 0.7 x 1028 molecules s-1, respectively. Jets were sought (but not found) in the white-light and ‘OH’ images reported here, suggesting that the jets reported by Knight and Schleicher (2009) are unique to CN. -

My Views on the Bible***

ABOUT THIS CURRENT VERSION I have made a few minor corrections in spelling and a handful of remarks for clarity's sake in the past few days. All the facts from the 3rd modification in 2012, however, remain unchanged despite the several great changes around the world. Thang Za Dal Hamburg August 19, 2020. MY VIEWS ON THE BIBLE AND CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS (3rd Modification) It is the 3rd modification of my “Interview” which was first publicized back on March 23, 1987. The original version was put on this website between March 2007 and May 2009. Then it was replaced in June 2009 with the 1st modification until March 23, 2012. Then once again it was replaced with the 2nd Modification on March 24, 2012, which remained on the website until September 6, 2012. Although I could have had expanded or changed radically many parts of the original version in light of the major changes in world affairs that have been taking place since 1987 I haven‘t done that. Only the styles of expression - and not the basic essences - of theological issues have been changed for the sake of clearity. Nearly all non-theological issues remain unchanged from the original version. In this present version only a very few changes and additions are made from the previous one. I have just added a new Item called On Western Philosophy (# 100), just because a number of people who have read my paper wanted to know about my opinion on this topic and I suppose there could probably be some more who have the same wish. -

THE GREAT CHRIST COMET CHRIST GREAT the an Absolutely Astonishing Triumph.” COLIN R

“I am simply in awe of this book. THE GREAT CHRIST COMET An absolutely astonishing triumph.” COLIN R. NICHOLL ERIC METAXAS, New York Times best-selling author, Bonhoeffer The Star of Bethlehem is one of the greatest mysteries in astronomy and in the Bible. What was it? How did it prompt the Magi to set out on a long journey to Judea? How did it lead them to Jesus? THE In this groundbreaking book, Colin R. Nicholl makes the compelling case that the Star of Bethlehem could only have been a great comet. Taking a fresh look at the biblical text and drawing on the latest astronomical research, this beautifully illustrated volume will introduce readers to the Bethlehem Star in all of its glory. GREAT “A stunning book. It is now the definitive “In every respect this volume is a remarkable treatment of the subject.” achievement. I regard it as the most important J. P. MORELAND, Distinguished Professor book ever published on the Star of Bethlehem.” of Philosophy, Biola University GARY W. KRONK, author, Cometography; consultant, American Meteor Society “Erudite, engrossing, and compelling.” DUNCAN STEEL, comet expert, Armagh “Nicholl brilliantly tackles a subject that has CHRIST Observatory; author, Marking Time been debated for centuries. You will not be able to put this book down!” “An amazing study. The depth and breadth LOUIE GIGLIO, Pastor, Passion City Church, of learning that Nicholl displays is prodigious Atlanta, Georgia and persuasive.” GORDON WENHAM, Adjunct Professor “The most comprehensive interdisciplinary of Old Testament, Trinity College, Bristol synthesis of biblical and astronomical data COMET yet produced. -

Comets in UV

Comets in UV B. Shustov1 • M.Sachkov1 • Ana I. G´omez de Castro 2 • Juan C. Vallejo2 • E.Kanev1 • V.Dorofeeva3,1 Abstract Comets are important “eyewitnesses” of So- etary systems too. Comets are very interesting objects lar System formation and evolution. Important tests to in themselves. A wide variety of physical and chemical determine the chemical composition and to study the processes taking place in cometary coma make of them physical processes in cometary nuclei and coma need excellent space laboratories that help us understand- data in the UV range of the electromagnetic spectrum. ing many phenomena not only in space but also on the Comprehensive and complete studies require for ad- Earth. ditional ground-based observations and in-situ exper- We can learn about the origin and early stages of the iments. We briefly review observations of comets in evolution of the Solar System analogues, by watching the ultraviolet (UV) and discuss the prospects of UV circumstellar protoplanetary disks and planets around observations of comets and exocomets with space-born other stars. As to the Solar System itself comets are instruments. A special refer is made to the World Space considered to be the major “witnesses” of its forma- Observatory-Ultraviolet (WSO-UV) project. tion and early evolution. The chemical composition of cometary cores is believed to basically represent the Keywords comets: general, ultraviolet: general, ul- composition of the protoplanetary cloud from which traviolet: planetary systems the Solar System was formed approximately 4.5 billion years ago, i.e. over all this time the chemical composi- 1 Introduction tion of cores of comets (at least of the long period ones) has not undergone any significant changes. -

The Photometric Study of the Comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin)

The Photometric Study of the Comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin) Machchema Jankla, Kamal Baha, Nakared Inthana and Krit Boonsiriseth Mahidol Wittayanusorn School,Nakhonpathom; Chakkham Khanathon School,Lamphun;Azizstan School, Patani; Chulalongkorn University Demonstration Elementary School, Bangkok,Thailand [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This work studies the brightness of comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin) when it came closer to the Earth in 2009. We found that the comet’s brightness brightened from 12 mag in January 2009 and increased until the 25th of February when the brightness peaked. The brightness reached the highest magnitude which was 6.44 that day and then it started to decrease. We compare our observations with the theoretical prediction from the JPL Horizons Ephemeris and found that the light curve has similar shape but the normalization differs slightly. Introduction The comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin) comet is a special comet in this decade because it had two tails in a different directions (the “anti-tail”). Lulin’s orbit is nearly parallel with the orbit of the earth so when it got closer to the earth, the dust tail that is left along the comet’s otbit appeared in one direction while the ion tail which is caused by the solar wind and always points directly away from the Sun appears to be in the opposite direction. The relative position between the Earth, the comet and the Sun at the time of Lulin’s closest approach which resulted in Lulin’s tails pointing to different directions is shown in Fig. 1. We studied this unique comet photometrically by observing it with the Robotic Optical Transient Search Experiment (ROTSE)’s 0.45-meter robotic telescope (www.rotse.net) in Texas, USA, remotely from January – February 2009. -

Comet Kohoutek (NASA 990 Convair )

Madrid, UCM, Oct 27, 2017 Comets in UV Shustov B., Sachkov M., Savanov I. Comets – major part of minor body population of the Solar System There are a lot of comets in the Solar System. (Oort cloud contains cometary 4 bodies which total mass is ~ 5 ME , ~10 higher than mass of the Main Asteroid Belt). Comets keep dynamical, mineralogical, chemical, and structural information that is critically important for understanding origin and early evolution of the Solar System. Comets are considered as important objects in the aspect of space threats and resources. Comets are intrinsically different from one another (A’Hearn+1995). 2 General comments on UV observations of comets Observations in the UV range are very informative, because this range contains the majority of аstrophysically significant resonance lines of atoms (OI, CI, HI, etc.), molecules (CO, CO2, OH etc.), and their ions. UV background is relatively low. UV imaging and spectroscopy are both widely used. In order to solve most of the problems, the UV data needs to be complemented observations in other ranges including ground-based observations. 3 First UV observations of comets from space Instruments Feeding Resolu Spectral range Comets Found optics tion Orbiting Astronomical 4x200mm ~10 Å 1100-2000 Å Bennett OH (1657 Å) Observatory (OAO-2) ~20 Å 2000-4000 Å С/1969 Y1 OI (1304 Å) 2 scanning spectrophotometers Launched in 1968 Orbiting Geophysical ~100cm2 Bennett Lyman-α Observatory (OGO-5) С/1969 Y1 halo Launched in 1968 Aerobee sounding D=50mm ~1 Å 1100-1800 Å Tago- Lyman-α halo rocket Sato- wide-angle all-reflective Kosaka spectrograph С/1969 Y1 Launched in 1970 Skylab 3 space station D=75mm Kohoutek Huge Lyman- Launched in 1973 С/1969 Y1 α halo NASA 990 Convair D=300mm Kohoutek OH (3090Å) aircraft. -

Activity and Composition of Comet Lulin

EPSC Abstracts, Vol. 4, EPSC2009-55, 2009 European Planetary Science Congress, © Author(s) 2009 Activity and composition of comet Lulin D. Bodewits (1,2), G.L. Villanueva (2,3), M.J. Mumma (2), W. Landsman(4), J. A. Carter (5) and A. M. Read (5) (1) NASA Postdoctoral Fellow, [email protected], (2) NASA GSFC, Solar System Exploration Divison, Greenbelt MD 20771, USA, (3) Dept. of Physics, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C., USA, (4) NASA GSFC, Astrophysics Science Divison, Greenbelt MD 20771 (5) Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 1RH, UK Abstract The abundance of native ices in comet nuclei is a fundamental observational constraint in cosmogony. An important unresolved question is the extent to which the composition of pre- cometary ices varied with distance from the young sun. Our fundamental objective is to build a taxonomy based on cometary volatile composition instead of orbital dynamics [1]. The Swift space telescope [2] is unique in combining gamma ray, UV and X-ray instruments. Swift’s UV-optical grisms (175-520 nm), which have not been extensively used before this campaign, encompass known cometary + fluorescence bands (e.g., CO2 , OH, CO, NH, CS, CN, etc.) that can quantify and track the water and organic ice chemistry in the coma (see Figure 1). Until the scheduled repairs of HST’s STIS, Swift is the sole space-borne observatory that can characterize the molecular composition of a comet at UV-optical wavelengths. Through its rapid cadence, Swift is perfectly suited to characterize changes in the temporal development and composition of released gas. -

The GALEX Comets

15.11: The GALEX Comets J. P. Morgenthaler, W. M. Harris, M. R. Combi, P. D. Feldman, and H. A. Weaver October 2009 DPS Meeting Abstract The Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) has observed 6 comets since 2005 (C/2004 Q2 (Machholz), 9P/Tempel 1, 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 Fragments B and C, 8P/Tuttle and C/2007 N3 (Lulin). GALEX is a NASA Small Explorer (SMEX) mission designed to map the history of star forma- tion in the Universe. It is also well suited to cometary coma studies because ◦ of its high sensitivity and large field of view (1.2 ). OH and CS in the NUV (1750 – 3100 A)˚ are clearly detected in all of the comet data. The FUV (1340 – 1790 A)˚ channel recorded data during three of the comet observations and detects the bright C I 1561 and 1657 A˚ multiplets. We also see evidence + of S I 1475 A˚ in the FUV. NEW: we clearly detect CO emission in the NUV and CO Fourth positive emission in the FUV. The GALEX data were recorded with photon counting detectors, so it has been possible to reconstruct direct-mode and objective grism images in the reference frame of the comet. We have also created software which maps coma models onto the GALEX grism images for comparison to the data. We will present the data cleaned with automated catalog-based methods and a preliminary hand-fit to the data using simple Haser-based models. A more thorough hand-cleaning of the data from the contaminating effects of background sources is the last major reduction task to be done. -

Comet Hyakutake Passes the Earth Credit & Copyright: Doug Zubenel

Comet Hyakutake Passes the Earth Credit & Copyright: Doug Zubenel (TWAN) Two Tails of Comet Lulin Credit & Copyright: Richard Richins (NMSU) A Tale of Comet Holmes Credit & Copyright: Ivan Eder and (inset) Paolo Berardi The Dust and Ion Tails of Comet Hale-Bopp Credit & Copyright: John Gleason (Celestial Images) The Tails of Comet NEAT (Q4) Credit & Copyright: Chris Schur Tails Of Comet LINEAR Credit & Copyright: Jure Skvarc, Bojan Dintinjana, Herman Mikuz (Crni Vrh Observatory, Slovenia) Two Tails of Comet West Credit: Observatoire de Haute, Provence, France TEACHER’S NOTES: APOD: 2009 December 16 - Comet Hyakutake Passes the Earth Explanation: In 1996, an unexpectedly bright comet passed by planet Earth. Discovered less than two months before, Comet C/1996 B2 Hyakutake came within only 1/10th of the Earth-Sun distance from the Earth in late March. At that time, Comet Hyakutake, dubbed the Great Comet of 1996, became the brightest comet to grace the skies of Earth in 20 years. During its previous visit, Comet Hyakutake may well have been seen by the stone age Magdalenian culture, who 17,000 years ago were possibly among the first humans to live in tents as well as caves. Pictured above near closest approach as it appeared on 1996 March 26, the long ion and dust tails of Comet Hyakutake are visible flowing off to the left in front of a distant star field that includes both the Big and Little Dippers. On the far left, the blue ion tail appears to have recently undergone a magnetic disconnection event. On the far right, the comet's green-tinted coma obscures a dense nucleus of melting dirty ice estimated to be about 5 kilometers across. -

Matt Dennis Grew up in and Around the Greater St

Production Rates and Spin Temperatures of Volatiles in Comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin) Matthew A Dennis University of Missouri-St. Louis Adviser: Dr. Erika Gibb Abstract We examine spectra taken of comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin) in an effort to identify production rates of organic molecules present within the comet’s coma. We also indentify the temperature range at which the comet formed by examining the ortho/para ratio of the comet’s water ices. These observations will contribute to a growing catalog of chemical conditions within comets, which will in turn lead to a better understanding of the conditions in the early solar system. Introduction Comets are icy bodies thought to have coalesced during the solar system’s formation. Comets are mostly made of water and dust, but it is now known that they also harbor many of the volatile chemicals necessary for life. The study of volatiles in comets is an important link to understanding the formation of the solar system. By studying the composition of comets, astronomers gain many insights into conditions under which the comet formed, thereby strengthening our models for the behavior of the early protoplanetary disk. Many astronomers assert that comets may be responsible for the current life-friendly conditions on Earth (via the delivery of water and volatiles to the planet), and perhaps even for life itself. Models of the formation of the solar system have to include the appearance of water and organic molecules on Earth, which facilitated the development of life. Ongoing research into the composition, formation, and movements of comets and other small bodies is key to the development of these models. -

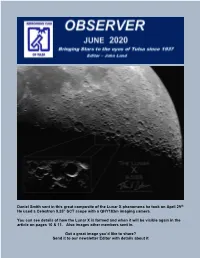

Daniel Smith Sent in This Great Composite of the Lunar X Phenomena He Took on April 29Th He Used a Celestron 9.25” SCT Scope with a Qhy183m Imaging Camera

Daniel Smith sent in this great composite of the Lunar X phenomena he took on April 29th He used a Celestron 9.25” SCT scope with a QHY183m imaging camera. You can see details of how the Lunar X is formed and when it will be visible again in the article on pages 10 & 11. Also images other members sent in. Got a great image you’d like to share? Send it to our newsletter Editor with details about it In this Issue 1 Cover – Lunar X photo by Daniel Smith 2 Upcoming Events 3 President’s Message– by Tamara Green Health Guidelines for Observatory nights 4 June Sky events – Planets and Comets 5-8 Interested in Comets and earning an observing certificate By Stan Davis 9 ACT members Daniel Smith & Adam Koloff featured in Tulsa People magazine 10-11 Lunar X explained and member photos. 12 Treasurer’s Report – John Newton 13 Extreme Astronomer Test – are you one ? 14 Club meeting locations and maps 15 Club officers and contacts. Astronomy Club Events Details at http://astrotulsa.com/Events.aspx All Public Events for June and July 2020 are suspended Phased in Public Events for August and the Fall Are being formulated based on how the current Health situation evolves. Check our website www.AstroTulsa.com events section for updates Members ONLY Events with Social Distancing Guidelines in Effect JUNE: Friday, June 12, 8:30 PM Saturday, June 13, 8:30 PM (backup) Friday, June 19, 8:30 PM Saturday, June 20, 8:30 PM (backup) JULY: Friday, July 10, 8:30 PM Saturday, July 11 8:30 PM (backup) Friday, July 17, 8:30 PM Saturday, July 18, 8:30 PM (backup) . -

Chemical Composition of Comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin): Another "Atypical" Comet

Chemical composition of comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin): another "atypical" comet Proposed running head: Lulin: another “atypical” comet Erika L. Gibb1, Boncho P. Bonev2,3, Geronimo Villanueva2,3, Michael A. DiSanti3, Michael, J. Mumma3, Emily Sudholt1, Yana Radeva2,3 1 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Missouri - St Louis, St Louis, MO, 63121, USA 2 Department of Physics, The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC 20064, USA 3 Goddard Center for Astrobiology, Solar System Exploration Division, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, code 690, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA Submitted to Astrophysical Journal December 29, 2011 Editorial correspondence and proofs should be directed to ELG Erika Gibb 503 Benton Hall One University Blvd University of Missouri – St. Louis St. Louis, MO 63121 Phone: (314) 516-4145 Fax: (314) 516-6152 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We measured the volatile chemical composition of comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin) on three dates from 30 January to 1 February, 2009 using NIRSPEC, the high-resolution (λ/Δλ ≈ 25,000), long-slit echelle spectrograph at Keck 2. We sampled nine primary (parent) volatile species (H2O, C2H6, CH3OH, H2CO, CH4, HCN, C2H2, NH3, CO) and two product species (OH* and NH2). We also report upper limits for HDO and CH3D. C/2007 N3 (Lulin) displayed an unusual composition when compared to other comets. Based on comets measured to date, CH4 and C2H6 exhibited “normal” abundances relative to water, CO and HCN were only moderately depleted, C2H2 and H2CO were more severely depleted, and CH3OH was significantly enriched. Comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin) is another important and unusual addition to the growing population of comets with measured parent volatile compositions, illustrating that these studies have not yet reached the level where new observations simply add another sample to a population with well-established statistics.