A Week on Katahdin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation of a Rare Alpine Plant (Prenanthes Boottii) in the Face of Rapid Environmental Change

Conservation of a rare alpine plant (Prenanthes boottii) in the face of rapid environmental change Kristen Haynes SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry End of Season Report, 2014 Background The northeast alpine zone is one of our region’s rarest biological communities, comprised of a series of habitat islands totaling less than 35 km (figure 1; Capers et al. 2013). These mountaintop communities are hotbeds of local biodiversity, home to a suite of rare and endangered plant and animal species, including regional endemics as well as arctic species at the southern limit of their range. This biodiversity is now threatened by human-imposed environmental changes. Climate change is considered by Sala et al. (2010) to be the most important driver of biodiversity change in alpine ecosystems. Alpine communities are predicted to be highly susceptible to climate change for several reasons. First, high-elevation areas are warming faster than low-elevation areas (Wang et al. 2013). Second, the effects of climate change are predicted to be most severe for communities at climatic extremes, such as alpine communities (Pauli et al. 1996, Sala et al. 2010). Finally, the alpine biome is expected to contract as treelines and lower- elevation species move upward in elevation (Parmesan et al. 2006). There is already some evidence of advancing treelines and invasion of lowland species in the northeast alpine (Harsch et al. 2009; Nancy Slack, pers. comm.). In addition to climate change, northeast alpine species are threatened by high rates of nitrogen deposition and damage due to hiker trampling (Kimball and Weirach 2000). Figure 1. -

High Peaks Region Recreation Plan

High Peaks Region Recreation Plan An overview and analysis of the recreation, possibilities, and issues facing the High Peaks Region of Maine Chris Colin, Jacob Deslauriers, Dr. Chris Beach Fall 2008 Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust – High Peaks Initiative: The Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust (MATLT) was formed in June 2002 by a group of Mainers dedicated to the preservation of the natural qualities of the lands surrounding the Appalachian Trail in Maine. Following its campaign to acquire Mount Abraham and a portion of Saddleback Mountain, MATLT is embarking on a new initiative to research and document the ecological qualities of the entire Western Maine High Peaks Region. The MATLT website describes the region as follows: “The Western Maine High Peaks Region is the 203,400 acres roughly bounded by the communities of Rangeley, Phillips, Kingfield and Stratton. In this region, there are about 21,000 acres above 2700 feet. It is one of only three areas in Maine where the mountains rise above 4000 feet. The other two are the Mahoosuc Range and Baxter Park. Eight (8) of the fourteen (14) highest mountains in Maine are in this region (Sugarloaf, Crocker, South Crocker, Saddleback, Abraham, The Horn, Spaulding and Redington Peak.) These are all above 4000 feet. If one adds the Bigelow Range, across Route 27/16 from Sugarloaf, the region hosts ten (10) of the highest mountains (Avery Peak and West Peak added)). This area is comparable in size to Baxter Park but has 40% more area above 2700 feet.” Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 1 A. Purpose and Need for High Peaks Area Recreation Plan .................................................................... -

Crocker Mountain Unit Management Plan

Crocker Mountain Unit Management Plan Adopted April 2015 Appendices A. Public Consultation Process: Advisory Committee Members; Public Consultation Summary; Public Comments and Responses B. Guiding Statutes and Agreements • MRSA Title 12 • Commemorative Agreement Celebrating the Crocker Mountain Conservation Project • Letter to State of Maine from The Trust for Public Land – Crocker Mountain Ecological Reserve C. Integrated Resource Policy (IRP) Resource Allocations - Criteria and Management Direction D. Crocker Mountain Ecological Reserve Nomination E. Caribou Valley Road Easement F. Sources Appendix A: Public Review Process Advisory Committee Members; Public Consultation Process; Public Comments and Bureau Responses Flagstaff Region Advisory Committee Members: Name Organization Tarsha Adams Natanis Point Campground Rep. Jarrod S. Crockett House District 91 Debi Davidson Izaak Walton League Ernie DeLuca Brookfield White Pine Hydro LLC Thomas Dodd American Forest Management Eliza Donoghue Natural Resources Council of Maine Greg Drummond Claybrook Lodge Rep. Larry C. Dunphy House District 88 Dick Fecteau Maine Appalachian Trail Club Jennifer Burns Gray Maine Audubon Society Bob Luce Town of Carrabassett Valley Douglas Marble High Peaks Alliance Rick Mason E. Flagstaff Lake Property Owners Assoc. John McCatherin Carrabassett Valley Outdoor Association/C.V. ATV Club Bill Munzer JV Wing Snowmobile Club Claire Polfus Appalachian Trail Conservancy Josh Royte The Nature Conservancy Allan Ryder Timber Resource Group Senator Tom Saviello Senate District 18 Dick Smith Flagstaff Area ATV Club Ken Spalding Friends of Bigelow Josh Tauses Carrabassett Region Chapter, NEMBA Senator Rodney Whittemore Senate District 26 Kenny Wing none Charlie Woodworth Maine Huts & Trails A-1 Public Consultation Process: Plan Phase/Date Action/Meeting Focus Attendance/Responses Public Scoping July 15-16, 2014 Notice of Public Scoping Meeting Press release sent out; meeting notice published in papers. -

The Ecological Values of the Western Maine Mountains

DIVERSITY, CONTINUITY AND RESILIENCE – THE ECOLOGICAL VALUES OF THE WESTERN MAINE MOUNTAINS By Janet McMahon, M.S. Occasional Paper No. 1 Maine Mountain Collaborative P.O. Box A Phillips, ME 04966 © 2016 Janet McMahon Permission to publish and distribute has been granted by the author to the Maine Mountain Collaborative. This paper is published by the Maine Mountain Collaborative as part of an ongoing series of informational papers. The information and views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Maine Mountain Collaborative or its members. Cover photo: Caribou Mountain by Paul VanDerWerf https://www.flickr.com/photos/12357841@N02/9785036371/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ DIVERSITY, CONTINUITY AND RESILIENCE – THE ECOLOGICAL VALUES OF THE WESTERN MAINE MOUNTAINS Dawn over Crocker and Redington Mountains Photo courtesy of The Trust for Public Land, Jerry Monkman, EcoPhotography.com Abstract The five million acre Western Maine Mountains region is a landscape of superlatives. It includes all of Maine’s high peaks and contains a rich diversity of ecosystems, from alpine tundra and boreal forests to ribbed fens and floodplain hardwood forests. It is home to more than 139 rare plants and animals, including 21 globally rare species and many others that are found only in the northern Appalachians. It includes more than half of the United States’ largest globally important bird area, which provides crucial habitat for 34 northern woodland songbird species. It provides core habitat for marten, lynx, loon, moose and a host of other iconic Maine animals. Its cold headwater streams and lakes comprise the last stronghold for wild brook trout in the eastern United States. -

State of Maine Department of Conservation Land Use Regulation Commission

STATE OF MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION LAND USE REGULATION COMMISSION IN THE MATTER OF MAINE MOUNTAIN POWER, LLC ) BLACK NUBBLE WIND FARM ) ) PRE-FILED TESTIMONY REDINGTON TOWNSHIP, FRANKLIN ) APPALACHIAN MOUNTAIN CLUB COUNTY, MAINE ) DR. KENNETH D. KIMBALL ) ZONING PETITION ZP 702 ) I. INTRODUCTION My name is Kenneth Kimball. I hold a doctorate in botany from the University of New Hampshire, a Masters in zoology from the University of New Hampshire and a Bachelors of Science in ecology from Cornell University. I have been employed as the Research Director for the Appalachian Mountain Club since 1983. I have overall responsibility for the club’s research in the areas of air quality, climate change, northeastern alpine research, hydropower relicensing, windpower siting policy and land conservation and management. I was the organizer of the Northeastern Mountain Stewardship Conference, held in Jackson, NH in 1988, co-organizer of the National Mountain Conference held in Golden, CO in 2000 and one of the original founders of what is now the biannual Northeastern Alpine Stewardship Symposiums. I have conducted research on New Hampshire and Maine’s mountains, including on Mount Katahdin, Saddleback, Sunday River Whitecap and the Mahoosucs. I am currently the principal investigator of a NOAA-funded research project titled “Climate and air pollutant trends and their influence on the biota of New England’s higher elevation and alpine ecosystems”, which includes partner organizations the University of New Hampshire and Mount Washington Observatory. I have been involved in research and policy development related to windpower siting in the northeast for over a decade. I have organized and chaired several forums on the need for states to develop windpower siting policy in Massachusetts and New Hampshire and spoken at a number of forums on this need. -

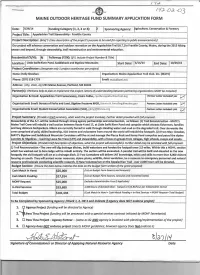

Sample MOHF Proposal

Project Title: Appalachian Trail (A.T.) Stewardship: Franklin County Organization: Maine Appalachian Trail Club. Inc., (MATC) Contact: Holly Sheehan, Club Coordinator Sponsoring Agency: Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry Fund Distribution Category: (2) “Acquisition and management of public lands, parks, wildlife conservation areas and public access and outdoor recreation sites and facilities.” Detailed Project Description and Background: Project conserves the best of Maine’s Outdoor heritage and demonstrates multiple and significant benefits relating to category designation: Organization’s mission and actions: Maine Appalachian Trail Club is a non-profit organization established in 1935. Our purpose is to construct, maintain and protect 267-miles of the Appalachian Trail along with 40- miles of side trails, shelters and campsites from Katahdin to Grafton Notch. MATC is more than a hiking club. Club volunteers build bog bridges and rock steps, construct shelters and toilets, clear downed trees, post signage, monitor corridor lands, and provide education to trail users. Our Maine Trail Crew builds bog bridges, stone steps and other tread way improvements that are beyond the scope of volunteer trail maintainers. Two MATC Caretakers based at Saddleback and Bigelow Mountains, as well as a Ridgerunner, at Gulf Hagas, provide Leave No Trace education to hikers. Volunteers are our foundation - each year a small army of committed Maine people log more than 20,000 hours taking responsibility for the Appalachian Trail in Maine. Project Description: Stewardship of the A.T., in 2015, will be in Franklin County through multiple courses of action and will be managed and powered by volunteers along with strong agency partnerships, as follows: Trail Reconstruction: MATC's Maine Trail Crew will rebuild a 2.5-mile trail section, between Route 4 and Route 17, at and approaching Little Swift River Pond and campsite. -

Using GIS to Assess Recreational Access in the High Peaks of Maine

Using GIS to Assess Recreational Access in the High Peaks of Maine Soren Denlinger ’20, Environmental Studies Program, Colby College, Waterville, Maine Introduction Maine’s High Peaks region, in the mountains of west-central part of the state, provides extensive recreational opportunities. Snowmobile, ski, mountain bike, and especially hiking trails serve as conduits for those seeking outdoor experiences (Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust, 2017). However, trailheads in the High Peaks region of Maine are scattered across both public and private land on a road network with varying levels of maintenance. These factors, in combination with long drive times and unplowed roads often keep potential visitors away from hiking centers (Clawson and Knetsch, 2011). The objective of this study was to analyze the region’s accessibility via road. Specifically, I wanted to know which trailheads were publicly owned and accessible in winter as well as roughly how much driving time is required to reach the trailheads. Methods I obtained road polylines and census block groups from the Maine Office of GIS. I downloaded U.S. Census Bureau statistics for 2006-2010 population and area at the census block group level from Social Explorer. I acquired aerial imagery from the USGS. I used Google Maps and Maine Trail Finder to identify 21 hiking trailheads and digitize corresponding, unmapped access roads using aerial imagery. Using personal knowledge, I added binary attributes to each trailhead to describe whether the trailhead was reachable by a normal car in the winter (if the road is regularly plowed). I also added an attribute to identify its ownership as public or private. -

Fall 2020 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Letter from the Editors

Autumn 2020 A close-up view of our chapter’s vibrancy and dedication. Fall 2020 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Letter from the Editors There is no doubt that this has been a strange summer. But, it’s been a Chair Kim Beauchemin good one. It has made us ever more grateful for the outdoors and the Vice Chair Michael Morin AMC community – for the sanctuary the woods and waters provide and Secretary Peter Eggleston the friendships, old and new, that have formed and grown even at a Treasurer Jose Schroen time when we are physically distant. As autumn takes hold, bringing its patchwork of gold, campfire orange, and sprite berry red to the hills Biking Neil Schutzman and forests of central MA, we are happy for the change. With it comes Communications Zenya Molnar a refresh of the mind and spirit and the reminder that life is truly Communications Alexandra Molnar fleeting and we must relish every moment, despite the challenges. Conservation Jonathan DiRodi Finance Christine Crepeault In this issue you will hear about the importance of using bear canisters Families Ingrid Molnar when backpacking as well as the story of a black man’s experiences Hiking Dana Perry with racism while hiking; and you can enjoy some photographs of Historian Michele Simoneau beautiful Worcester-area hikes from the summer. Leadership Paul Glazebrook Thank you to all our writers, photographers, and contributors. We are Membership Michael Hauck always looking for content and photos! If you’d like to contribute to the Mike Peckar Midstate Trail next edition, please send your submission to: Paddling David Elliott [email protected]. -

The Appalachian Trail Pt 1

The Appalachian Trail Part 1 Phyllida Willis One summer day in the early 1930s, I 'climbed my first mountain'. It was 400m Bear Mountain, about 60 miles up the Hudson River from Times Square, New York City, a 370m 'ascent' from the river. At the top, I was thrilled to read the sign, 'Appalachian Trail', 1200 miles to Mount Oglethorpe, Georgia, and 800 to Katahdin I, Maine! I wished that I might walk the whole Trail, at that time an impossibility. For 40 years I 'collected' bits and pieces of the Trail. In August, 1980, at·the end of a 34-mile backpack in the Green Mountains of Vermont, I was celebrating the completion of the last bit. The idea for a wilderness footpath along the crest of the Appalachian Mountains originated with Benton MacKaye, a forester, author and philosopher. In October, 1921, he published an article, 'An Appalachian Trail, a Project in Regional Planning,' in The]oumal ofthe American Institute ofArchitects. He proposed the Trail as a backbone, linking wilderness areas suitable for recreation that would be accessible to dwellers in the metropolitan areas along the Atlantic seaboard. He wrote, 'The old pioneer opened through the forest a path for the spread of civilization. His work was nobly done and life of the town and city is in consequence well upon the map throughout our country. Now comes the great task of holding this life in check-for it is just as bad to have too much of urbanisation as too little. America needs her forests and her wild spaces quite as much as her cities and her settled places.' The Trail extends NE for 2000 miles from 1160m Springer Mountain in Georgia (latitude 34°N, longitude 86°W) to 1610m Katahdin in Maine (latitude 46°N, longitude 68°W). -

Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Bigelow Mountain

Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance: Bigelow Mountain - Flagstaff Lake - North Branch Dead River Beginning with Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Habitat Bigelow Mountain- Flagstaff Lake- North Branch Dead River Biophysical Regions • Mahoosuc Rangely Lakes • Connecticut Lakes WHY IS THIS AREA SIGNIFICANT? Rare Animals This focus area is an acclaimed recreational destination that Bald Eagle Creeper encompasses a range of natural features and landscapes of Peregrine Falcon Rock Vole Tomah Mayfly Canada Lynx exceptional ecological value. The Bigelow Range supports a Bicknell’s Thrush variety of rare and sensitive ecosystems and species, along with hiking trails and spectacular views. Flagstaff Lake, Rare Plants the North Branch of the Dead River, and the surrounding Alpine Blueberry wetlands provide boating opportunities, important wildlife Alpine Sweet-grass habitat, and a high quality cold water fishery that supports Appalachian Fir-clubmoss wild brook trout. This area includes significant portions of Bigelow’s Sedge Boreal Bentgrass the Appalachian Trail and the Northern Forest Canoe Trail Dwarf Rattlesnake Root and provides habitat for seven Threatened or Endangered Fragrant Cliff Wood-fern species. Lapland Diapensia Lesser Wintergreen OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONSERVATION Mountain Sandwort Vasey’s Pondweed » Minimize recreational impacts on sensitive alpine areas through careful siting of trails and monitoring for overuse. Rare and Exemplary » Educate hikers on proper trail use to minimize off-trail Natural Communities impacts, especially in alpine areas. Acidic Cliff » Protect sensitive natural features through careful manage- Grassy Shrub Marsh ment planning on state-owned lands. Heath Alpine Ridge Lower-elevation Spruce - Fir Forest » Work with landowners to encourage sustainable forest Montane Spruce - Fir Forest management practices on private lands. -

High Peaks Wilderness Complex Unit Management Plan

Department of Environmental Conservation Office of Natural Resources - Region 5 High Peaks Wilderness Complex Unit Management Plan Wilderness Management for the High Peaks of the Adirondack Park March 1999 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation George E. Pataki, Governor John P. Cahill, Commissioner HIGH PEAKS UNIT MANAGEMENT PLAN FINAL DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................. 1 NEED FOR A PLAN .......................................... 3 MANAGEMENT GOALS ....................................... 4 SECTION I INTRODUCTION TO THE HIGH PEAKS WILDERNESS COMPLEX AREA OVERVIEW ...................................... 7 UNIT DESCRIPTIONS ................................... 7 Ampersand Primitive Area .............................. 7 Johns Brook Primitive Corridor .......................... 8 High Peaks Wilderness ................................ 8 Adirondack Canoe Route ............................... 8 BOUNDARY .......................................... 8 PRIMARY ACCESS ...................................... 9 SECTION II BIOPHYSICAL RESOURCES GEOLOGY ............................................10 SOILS ...............................................11 TERRAIN .............................................13 WATER ..............................................13 WETLANDS ...........................................16 CLIMATE ............................................16 AIR QUALITY .........................................17 OPEN SPACE ..........................................17 VEGETATION -

Winter 2017 Newsletter

Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust Winter 2017 Newsletter Appalachian Trail Maine: Next Century Update Since the Appalachian Trail Landscape Partnership was One of the efforts the Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust is launched in 2015, significant progress has been made involved in is the Regional Conservation Partnership Network in towards a comprehensive land protection strategy for the New England. These clusters of conservation organizations – Appalachian Trail landscape from Maine to Georgia. the High Peaks Initiative, Maine West, the Maine Mountain After the 2016 conference at the National Conservation Collaborative, Staying Connected Initiative, Hudson to Training Center in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, the Housatonic, and so on – will be vital in conserving the A.T. attendees were tasked with exploring new partnerships landscape in the coming years. and connections in order to broaden the reach on this The Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust is doing its part by landscape, which stretches for over two thousand miles working on a database of the A.T. landscape in Maine. This will from north to south and is dozens of miles wide in places. include information on five categories important for the These partners designated priority areas, which include protection of the A.T.: Scenery Along the Treadway, Views the Hundred Mile Wilderness and the Maine High Peaks Beyond the Corridor, American Heritage, Natural Resource region. They also came up with a vision to: Quality and Ecological Connectivity, and Visitor Experience. • bring together the expertise and funding We’re doing some really exciting work in these areas and this capacities of organizations, communities, and information will be pubic and sharable.