Considering Aaron Sorkin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

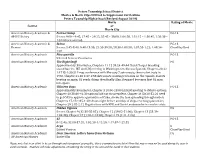

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

![List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8550/list-of-animated-films-and-matched-comparisons-posted-as-supplied-by-author-8550.webp)

List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]

Appendix : List of animated films and matched comparisons [posted as supplied by author] Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date Snow White and the G 1937 Saratoga ‘Passed’ Stella Dallas G Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio G 1940 The Great Dictator G The Grapes of Wrath unrated Bambi G 1942 Mrs. Miniver G Yankee Doodle Dandy G Cinderella G 1950 Sunset Blvd. unrated All About Eve PG Peter Pan G 1953 The Robe unrated From Here to Eternity PG Lady and the Tramp G 1955 Mister Roberts unrated Rebel Without a Cause PG-13 Sleeping Beauty G 1959 Imitation of Life unrated Suddenly Last Summer unrated 101 Dalmatians G 1961 West Side Story unrated King of Kings PG-13 The Jungle Book G 1967 The Graduate G Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner unrated The Little Mermaid G 1989 Driving Miss Daisy PG Parenthood PG-13 Beauty and the Beast G 1991 Fried Green Tomatoes PG-13 Sleeping with the Enemy R Aladdin G 1992 The Bodyguard R A Few Good Men R The Lion King G 1994 Forrest Gump PG-13 Pulp Fiction R Pocahontas G 1995 While You Were PG Bridges of Madison County PG-13 Sleeping The Hunchback of Notre G 1996 Jerry Maguire R A Time to Kill R Dame Hercules G 1997 Titanic PG-13 As Good as it Gets PG-13 Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date A Bug’s Life G 1998 Patch Adams PG-13 The Truman Show PG Mulan G 1998 You’ve Got Mail PG Shakespeare in Love R The Prince of Egypt PG 1998 Stepmom PG-13 City of Angels PG-13 Tarzan G 1999 The Sixth Sense PG-13 The Green Mile R Dinosaur PG 2000 What Lies Beneath PG-13 Erin Brockovich R Monsters, -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Aaron Sorkin's THE FARNSWORTH INVENTION

FLAT EARTH THEATRE THE FARNSWORTH INVENTION Page 1 of 3 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 14, 2015 CONTACT: Lindsay Eagle, Marketing and Publicity Chair [email protected] (954) 2603316 Brilliant Minds Go Head to Head to Invent Groundbreaking Technology in: Aaron Sorkin’s THE FARNSWORTH INVENTION WHAT: Flat Earth Theatre presents Aaron Sorkin’s THE FARNSWORTH INVENTION WHEN: THREE WEEKS ONLY: Friday, June 12th @ 8pm; Saturday, June 13th @ 8pm; Sunday, June 14th @ 2pm; Friday, June 19th @ 8pm; Saturday, June 20th @ 8pm; Sunday, June 21st @ 2pm; Monday, June 22nd @ 7:30pm; Thursday, June 25th @ 8pm; Friday, June 26th @ 8pm; and Saturday, June 27th @ 8pm WHERE: The Arsenal Center for the Arts, 321 Arsenal Street, Watertown, MA, 02472 TICKETS: $20 in advance; $25 at the door; $10 student rush PRESS NIGHT: Sunday, June 14th @ 2pm FOR PRESS TICKETS: Contact Lindsay Eagle, [email protected] or (954) 2603316 WATERTOWN, MA (May 14, 2015) Brilliant minds go head to head in THE FARNSWORTH INVENTION by Emmy Award–winning playwright and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin, creator of The West Wing and The Social Network. Upstart inventor Philo Farnsworth faces off against media mogul David Sarnoff in a nailbiting race to be the first to develop one of the twentieth century's most influential inventions: television. Directed by 2015 IRNE Award winner and fringe powerhouse Sarah Gazdowicz, THE FARNSWORTH INVENTION continues Flat Earth’s 2015 season “Progress and Peril,” stories of scientific progress and the lives it has ruined. Philo Farnsworth, a child prodigy raised on a farm in rural Idaho, has overcome adversity to create the world’s first electronic television. -

Computer Expert Predicts Future of Networking Farber Says That the Proposed Tufts Upgrade Not Extensive Enough He Said

~ ~ THETUFTS DAILY Volume XXXVIII, Number 55 [Where You Read It First Thursdav, April 22,1999 I Computer expert predicts future of networking Farber says that the proposed Tufts upgrade not extensive enough he said. Though he supported the proposed upgrade, he expressed by JEREMY WANGIVERSON trust lawsuit and is nationally bedroom or study. point, but other factors might im- doubts as to whether it was exten- Daily Editorial Board known for his “Interesting People Farber also spoke about the pede their development. sive enough. After 40 years of watching the mailing list,”adaily e-mail which potential dangers of powerful “Technology is easy; society “It’s being advertised as amajor field develop and grow, Univer- updates 25,000 readers on news telecommunications devices. isrough,”he explained,citingtaxes, leap,”he said. “It’sanice incremen- sity of Pennsylvania professor and on the technology front. Currently, anyone can be easily culture, and law as the major tal step in capability,” he added. computer science pioneer David Wiredmagazine wrotethat“his pinpointed every time they use a hurdles inhibiting technological TCCS Telecommunications Di- Farber has a unique perspective technical chops and the public credit card, ATM, or even a Tufts advancement. rector Lesley Tolman and associ- when it comes to predicting the spirit’’ make Farber the “Paul Re- ID. This ability to track people, Farber also discussed Internet ate Wilson Dillaway explained the future of the Internet. vere of the Digital Revolution.” he said, will be enhanced with 2, which Tufts is proposing as a advantages of the faster network. Farber spoke to nearly 50 Farber spoke for an hour before every improvement in technol- long-awaited upgrade to campus “Students will be able to use people, primarily faculty and staff, answering questions, centering ogy * network technology. -

Political Fiction Or Fiction About Politics. How to Operationalize a Fluid Genre in the Interwar Romanian Literature

ȘTEFAN FIRICĂ POLITICAL FICTION OR FICTION ABOUT POLITICS. HOW TO OPERATIONALIZE A FLUID GENRE IN THE INTERWAR ROMANIAN LITERATURE What’s in a Genre? A reader of contemporary genre theories is compelled to conclude that, one way or another, the idea of literary class has managed a narrow escape from obsolescence. Conceptual maximalism fell behind the pragmatic call to respond to a global cultural environment for which the task of grouping, structuring, organizing, labelling remains vital for a long list of reasons, of which marketing policies are not to be forgotten. The modern story of the field has seen many twists and turns. After some theories of genre evolutionism – derived more or less from Darwinism – consumed their heyday in the 1890s–1920s1, Bakhtin (1937) took a decisive step toward a “historical poetics”, before Wellek, Warren (1948), Northrop Frye (1957), and Käte Hamburger (1957), and, later on, Gérard Genette (1979), Alastair Fowler (1982), or Jean-Marie Schaeffer (1989) returned to self- styled mixtures of formalism and historicism2. The study which pushed forward the scholarship in the field was, surprisingly or not, a fierce deconstruction of the “madness of the genre”, perceived as a self- defeating theory and practice of classification, highly necessary and utterly impossible at the same time. In his usual paradoxical manner, Derrida (1980) construes the relationship between the individual work and its set as one of 1 See, for instance: Ferdinand Brunetière, L’évolution des genres dans l’histoire de la littérature, Paris, Hachette, 1890–1892; Albert Thibaudet, Le liseur de romans, Paris, G. Crès et Cie, 1925; Viktor Shklovsky, O теории прозы [On the Theory of Prose], Москва, Издательств o “Федерация”, 1925. -

Law and Resistance in American Military Films

KHODAY ARTICLE (Do Not Delete) 4/15/2018 3:08 PM VALORIZING DISOBEDIENCE WITHIN THE RANKS: LAW AND RESISTANCE IN AMERICAN MILITARY FILMS BY AMAR KHODAY* “Guys if you think I’m lying, drop the bomb. If you think I’m crazy, drop the bomb. But don’t drop the bomb just because you’re following orders.”1 – Colonel Sam Daniels in Outbreak “The obedience of a soldier is not the obedience of an automaton. A soldier is a reasoning agent. He does not respond, and is not expected to respond, like a piece of machinery.”2 – The Einsatzgruppen Case INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 370 I.FILMS, POPULAR CULTURE AND THE NORMATIVE UNIVERSE.......... 379 II.OBEDIENCE AND DISOBEDIENCE IN MILITARY FILMS .................... 382 III.FILM PARALLELING LAW ............................................................. 388 IV.DISOBEDIENCE, INDIVIDUAL AGENCY AND LEGAL SUBJECTIVITY 391 V.RESISTANCE AND THE SAVING OF LIVES ....................................... 396 VI.EXPOSING CRIMINALITY AND COVER-UPS ................................... 408 VII.RESISTERS AS EMBODIMENTS OF INTELLIGENCE, LEADERSHIP & Permission is hereby granted for noncommercial reproduction of this Article in whole or in part for education or research purposes, including the making of multiple copies for classroom use, subject only to the condition that the name of the author, a complete citation, and this copyright notice and grant of permission be included in all copies. *Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Manitoba; J.D. (New England School of Law); LL.M. & D.C.L. (McGill University). The author would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance in reviewing, providing feedback and/or making suggestions: Drs. Karen Crawley, Richard Jochelson, Jennifer Schulz; Assistant Professor David Ireland; and Jonathan Avey, James Gacek, Paul R.J. -

April 2020 Delray Beach, Florida

PALM GREENS PULSE APRIL 2020 DELRAY BEACH, FLORIDA YOU ARE HERE! 2 Palm Greens Pulse Palm Greens Pulse IN THIS ISSUE 561-499-5444 PAGE NO. ARTICLES 3 Condo 1 & Condo 2 4 From the Editor & Recreation Board 5 Men’s Club & Women’s club 6 Entertainment Committee & President/Treasurer V.P./Managing Editor Andrea Goldstein Mel Clapman Tennis Committee 7 Alliance of Delray & Tennis Social Club 8 Four Seasons & AUM Article Gift Card Scams 9 The Health Room & Time Saving Tips Production Manager Advertising Manager/Secretary 10 Tennis Pro & POI Beth Villanova Rhoda Misikoff Officers AFTER PAGE 10 Andrea Goldstein, President Mel Clapman, Vice-President Coronavirus Friday Night Movie Directors Gloria Kostrzecha Cele Fagan Beth Villanova Nobody asked me Sharon Mossovitz Rachel Rodgers Rhoda Bermon We Care Channel 63 Mel Clapman DISCLAIMER The Unit Owners Association of Palm Greens (UOAPG) and its publication, The Palm Greens Pulse, are not responsible for the services, products and/or claims made by our adver- tisers. We welcome articles of interest pertaining to Palm Greens as well as black and white photos. All submissions are subject to approval by the editor. Please address all correspondence to: The Palm Greens Pulse – 5801 Via Delray – Delray Beach FL 33484. We Office Hours request all articles be sent to The Pulse via email – Monday-Friday [email protected]. 9:00 AM - 5:30 PM Saturday 10:00 AM - 1:00 PM Appointments Suggested NW Corner of Hagen Ranch Rd. & Flavor Pict Rd. Whitworth Farms Office | 561.736.3880 12393 Hagen Ranch, Suite 301 Toll Free | 1.877.736.3880 Boynton Beach, FL 33437 Fax | 561.737.3035 visit us at www.sandctravel.com Email | [email protected] April 2020 3 CONDO 2 CONDO 1 by Allen Tirone We are approaching the time when most seasonal unit owners prepare to leave their units unoccupied Hard to believe but it’s already that time of year for extended periods of time as they return to their when our snowbirds return to their summer homes. -

Utopia, Myth, and Narrative

Utopia, Myth, and Narrative Christopher YORKE (University of Glasgow) I: Introduction [I]n the 1920s and 1930s…Fascist theorists…adapting the language of Georges Sorel, grandiloquently proclaimed the superiority of their own creative myths as ‘dynamic realities,’ spontaneous utterances of authentic desires, over the utopias, which they dismissed as hollow rationalist constructs.1 - Frank and Fritzie Manuel We have created a myth, this myth is a belief, a noble enthusiasm; it does not need to be reality, it is a striving and a hope, belief and courage. Our myth is the nation, the great nation which we want to make into a concrete reality for ourselves.2 - Benito Mussolini, October 1922; from speech given before the ‘March on Rome’ One of the most historically recent and damaging blows to the reputation of utopianism came from its association with the totalitarian regimes of Hitler’s Third Reich and Mussolini’s Fascist party in World War II and the prewar era. Being an apologist for utopianism, it seemed to some, was tantamount to being an apologist for Nazism and all of its concomitant horrors. The fantasy principle of utopia was viewed as irretrievably bound up with the irrationalism of modern dictatorship. While these conclusions are somewhat understandable given the broad strokes that definitions of utopia are typically painted with, I will show in this paper that the link between the mythos of fascism and the constructs of utopianism results from an unfortunate conflation at the theoretical level. The irrationalism of any mass ethos and the rationalism of the thoughtful utopian planner are, indeed, completely at odds with each other. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

49Th USA Film Festival Schedule of Events

HIGH FASHION HIGH FINANCE 49th Annual H I G H L I F E USA Film Festival April 24-28, 2019 Angelika Film Center Dallas Sienna Miller in American Woman “A R O L L E R C O A S T E R O F FABULOUSNESS AND FOLLY ” FROM THE DIRECTOR OF DIOR AND I H AL STON A F I L M B Y FRÉDERIC TCHENG prODUCeD THE ORCHARD CNN FILMS DOGWOOF TDOG preSeNT a FILM by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG IN aSSOCIaTION WITH pOSSIbILITy eNTerTaINMeNT SHarp HOUSe GLOSS “HaLSTON” by rOLaND baLLeSTer CO- DIreCTOr OF eDITeD MUSIC OrIGINaL SCrIpTeD prODUCerS STepHaNIe LeVy paUL DaLLaS prODUCer MICHaeL praLL pHOTOGrapHy CHrIS W. JOHNSON by ÈLIa GaSULL baLaDa FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG SUperVISOr TraCy MCKNIGHT MUSIC by STaNLey CLarKe CINeMaTOGrapHy by aarON KOVaLCHIK exeCUTIVe prODUCerS aMy eNTeLIS COUrTNey SexTON aNNa GODaS OLI HarbOTTLe LeSLey FrOWICK IaN SHarp rebeCCa JOerIN-SHarp eMMa DUTTON LaWreNCe beNeNSON eLySe beNeNSON DOUGLaS SCHWaLbe LOUIS a. MarTaraNO CO-exeCUTIVe WrITTeN, prODUCeD prODUCerS ELSA PERETTI HARVEY REESE MAGNUS ANDERSSON RAJA SETHURAMAN FeaTUrING TaVI GeVINSON aND DIreCTeD by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG Fest Tix On@HALSTONFILM WWW.HALSTON.SaleFILM 4 /10 IMAGE © STAN SHAFFER Udo Kier The White Crow Ed Asner: Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss Constance Towers On Stage and Off Timothy Busfield Melissa Gilbert Jeff Daniels in Guest Artist Bryn Vale and Taylor Schilling in Family Denise Crosby Laura Steinel Traci Lords Frédéric Tcheng Ed Zwick Stephen Tobolowsky Bryn Vale Chris Roe Foster Wilson Kurt Jacobsen Josh Zuckerman Cheryl Allison Eli Powers Olicer Muñoz Wendy Davis in Christina Beck -

226 Jacques Ranciére the Politics of Literature. Cambridge

Philosophy in Review XXXIII (2013), no. 3 Jacques Ranciére The Politics of Literature. Cambridge: Polity Press 2011. 224 pages $69.95 (cloth ISBN 978–0–7456–4530–8); $24.95 (paper ISBN 978–0– 7456–4531–5) The Brothers Karamazov is not only a superb novel but contains theological and philosophical material which arouses (holy) envy even in the most charitable theologian and philosopher. As a title, Jacques Ranciére’s The Politics of Literature can espouse a similar type of envy. While one should not judge a book by its cover (or title), it was those four words that drew me to the work and the opportunity to review it. Unlike the Jewish people who were said to accept the Torah before God even articulated its parameters (“we will do and we will obey”), I should have inquired and investigated more first before doing anything. Ranciére’s work is a collection of ten nebulously linked, previously published essays translated from the French by Julie Rose (the French collection was published in 2006). The title of the book is also the title of its first chapter. The essay (and book) opens: “The politics of literature is not the same thing as the politics of writers. It does not concern the personal engagements of writers in the social or political struggles of their times. Neither does it concern the way writers represent social structures, political movements or various identities in their books” (3). Sadly, it was precisely in hope of further examining those elements that attracted me to the work. As I am a theologian espousing postcolonial, liberation, and feminist approaches to texts, drawing upon my literary background and developing work in ethics and politics, I can only be candid in acknowledging that it was a rocky beginning for this reviewer, to say the least.