Constitutional Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teks-Ucapan-Pengumuman-Kabinet

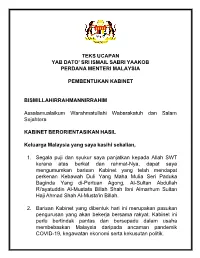

TEKS UCAPAN YAB DATO’ SRI ISMAIL SABRI YAAKOB PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA PEMBENTUKAN KABINET BISMILLAHIRRAHMANNIRRAHIM Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh dan Salam Sejahtera KABINET BERORIENTASIKAN HASIL Keluarga Malaysia yang saya kasihi sekalian, 1. Segala puji dan syukur saya panjatkan kepada Allah SWT kerana atas berkat dan rahmat-Nya, dapat saya mengumumkan barisan Kabinet yang telah mendapat perkenan Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah Ibni Almarhum Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Al-Musta'in Billah. 2. Barisan Kabinet yang dibentuk hari ini merupakan pasukan pengurusan yang akan bekerja bersama rakyat. Kabinet ini perlu bertindak pantas dan bersepadu dalam usaha membebaskan Malaysia daripada ancaman pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi serta kekusutan politik. 3. Umum mengetahui saya menerima kerajaan ini dalam keadaan seadanya. Justeru, pembentukan Kabinet ini merupakan satu formulasi semula berdasarkan situasi semasa, demi mengekalkan kestabilan dan meletakkan kepentingan serta keselamatan Keluarga Malaysia lebih daripada segala-galanya. 4. Saya akui bahawa kita sedang berada dalam keadaan yang getir akibat pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi dan diburukkan lagi dengan ketidakstabilan politik negara. 5. Berdasarkan ramalan Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO), kita akan hidup bersama COVID-19 sebagai endemik, yang bersifat kekal dan menjadi sebahagian daripada kehidupan manusia. 6. Dunia mencatatkan kemunculan Variant of Concern (VOC) yang lebih agresif dan rekod di seluruh dunia menunjukkan mereka yang telah divaksinasi masih boleh dijangkiti COVID- 19. 7. Oleh itu, kerajaan akan memperkasa Agenda Nasional Malaysia Sihat (ANMS) dalam mendidik Keluarga Malaysia untuk hidup bersama virus ini. Kita perlu terus mengawal segala risiko COVID-19 dan mengamalkan norma baharu dalam kehidupan seharian. -

Trends in Southeast Asia

ISSN 0219-3213 2016 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia THE EXTENSIVE SALAFIZATION OF MALAYSIAN ISLAM AHMAD FAUZI ABDUL HAMID TRS9/16s ISBN 978-981-4762-51-9 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 789814 762519 Trends in Southeast Asia 16-1461 01 Trends_2016-09.indd 1 29/6/16 4:52 PM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) was established in 1968. It is an autonomous regional research centre for scholars and specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia. The Institute’s research is structured under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS) and Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and through country- based programmes. It also houses the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), Singapore’s APEC Study Centre, as well as the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and its Archaeology Unit. 16-1461 01 Trends_2016-09.indd 2 29/6/16 4:52 PM 2016 no. 9 Trends in Southeast Asia THE EXTENSIVE SALAFIZATION OF MALAYSIAN ISLAM AHMAD FAUZI ABDUL HAMID 16-1461 01 Trends_2016-09.indd 3 29/6/16 4:52 PM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2016 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. The author is wholly responsible for the views expressed in this book which do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher. -

Vol 2 June 2016 Prime Minister of Malaysia, Dato Sri Mohd

PP 8307/12/2012(032066) Vol 2 June 2016 Prime Minister of Malaysia, Dato Sri Mohd Najib being greeted by ASLI Chairman, Tan Sri Dr. Jeffrey Cheah and ASLI Director, Tan Sri Razman Hashim. Prime Minister of Malaysia, Dato Sri Mohd Najib being presented with a portrait of his father, the 2nd Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tan Sri Dr. Michael Yeoh, ASLI CEO with Managing Director Tun Abdul Razak by Tan Sri Abdul Halim Ali. Looking on are Dato Nizam Razak, Tun Ahmad Sarji and Tan Sri Dr. Michael Yeoh. of International Monetary Fund (IMF), Ms. Christine Lagarde Prime Minister of Malaysia, Dato Sri Mohd Najib with ASLI CEO, Tan Sri Dr. Michael Yeoh Deputy Prime Minister Dato Seri Zahid Hamidi with Tan Sri Dr. Michael Yeoh Tan Sri Dr. Jeffrey Cheah, ASLI Chairman welcoming former Prime Tan Sri Dr. Michael Yeoh, ASLI CEO and Mr. Max Say, ASLI Senior Vice President greeting the Chairman of Minister of Malaysia Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. Russia’s Upper House of Parliament whilst Dr. Sautov, Chairman of the Russia Business Council looks on. NEWSLETTER OF THE ASIAN STRATEGY & LEADERSHIP INSTITUTE THE LEGACY OF LEADERSHIP Commemorative Seminar on 2nd Tun Abdul Razak > 14 January 2016 The Prime Minister of Malaysia, Dato Sri Mohd Najid launching the book on the 2nd Prime Minister Tun ASLI Chairman, Tan Sri Dr. Jeffrey Cheah greeting the Prime Minister Abdul Razak with PNB Chairman, Tun Ahmad Sarji at the Seminar. Looking on are Tan Sri Dr. Michael of Malaysia Dato Sri Mohd Najib on his arrival. Yeoh, Tan Sri Abdul Halim Ali and Dato Nizam Razak. -

Sexuality, Islam and Politics in Malaysia: a Study of the Shifting Strategies of Regulation

SEXUALITY, ISLAM AND POLITICS IN MALAYSIA: A STUDY OF THE SHIFTING STRATEGIES OF REGULATION TAN BENG HUI B. Ec. (Soc. Sciences) (Hons.), University of Sydney, Australia M.A. in Women and Development, Institute of Social Studies, The Netherlands A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2012 ii Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation was made possible with the guidance, encouragement and assistance of many people. I would first like to thank all those whom I am unable to name here, most especially those who consented to being interviewed for this research, and those who helped point me to relevant resources and information. I have also benefited from being part of a network of civil society groups that have enriched my understanding of the issues dealt with in this study. Three in particular need mentioning: Sisters in Islam, the Coalition for Sexual and Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies (CSBR), and the Kartini Network for Women’s and Gender Studies in Asia (Kartini Asia Network). I am grateful as well to my colleagues and teachers at the Department of Southeast Asian Studies – most of all my committee comprising Goh Beng Lan, Maznah Mohamad and Irving Chan Johnson – for generously sharing their intellectual insights and helping me sharpen mine. As well, I benefited tremendously from a pool of friends and family who entertained my many questions as I tried to make sense of my research findings. My deepest appreciation goes to Cecilia Ng, Chee Heng Leng, Chin Oy Sim, Diana Wong, Jason Tan, Jeff Tan, Julian C.H. -

P. 6 Maritime Forces………………

Editorial Team Inside this Brief Captain (Dr.) Gurpreet S Khurana Maritime Security…………………………….p. 6 Commander Dinesh Yadav Ms Neelima Joshi, Ms Preeti Yadav Maritime Forces………………………………p. 29 Address Shipping,Ports and Ocean Economy….p. 37 National Maritime Foundation Varuna Complex, NH- 8 Geopolitics,Marine Enviroment Airport Road New Delhi-110 010, India and Miscellaneous……………………...….p. 51 Email: [email protected] Acknowledgement: ‘Making Waves’ is a compilation of maritime news and news analyses drawn from national and international online sources. Drawn directly from original sources, minor editorial amendments are made by specialists on maritime affairs. It is intended for academic research, and not for commercial use. NMF expresses its gratitude to all sources of information, which are cited in this publicationPage. 1 of 73 Malaysian Officials Fish for a Response to Chinese Trawler Incursion U.S. Coast Guard, Japan Partner to Improve Port Security U.S. Navy Seizes Weapons Likely Headed to Yemen For first time, Japan will send Ise destroyer into the South China Sea Chinese Vessel Ducks for Cover in Vietnamese Territorial Waters Three day coastal security exercise draws to a close Why the South China Sea could be the next global flashpoint US Kicks Off New Maritime Security Initiative for Southeast Asia Page 2 of 73 Indian Navy' First Training Squadron deployed in Thailand USS Blue Ridge Makes Port Call in Goa Pakistan Navy successfully test-fires shore-based anti-ship missile US Navy leads 30-nation maritime exercise in Middle -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

DAP's Ngeh Gives Ismail Sabri 24 Hours to Apologise for His Anti

DAP’s Ngeh gives Ismail Sabri 24 hours to apologise for his anti-Chinese post The Malaysian Insider March 11, 2015 By Eileen Ng DAP's Datuk Ngeh Koo Ham has given an Umno minister a final ultimatum: apologise for his incendiary anti-Chinese remarks within 24 hours or face legal action. He said the notice of demand is ready, but has not been served on Agriculture and Agro-Based Industries minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaacob as he is still waiting for an apology. "I will give him another 24 hours to apologise," he said at a press conference at the parliament lobby today. Ismail had come under fire last month for his Facebook posting urging Malays to boycott Chinese traders. He said Malay consumers had a role in helping Putrajaya fight profiteers by using their collective power to lower the price of goods. The minister is also embroiled in an allegation he reportedly made of Ngeh, whom the former said had shares in the popular OldTown White Coffee chain owned by OldTown Bhd. Ngeh subsequently threatened to sue the minister for labelling him and his family anti-Islam, after Ismail failed to meet the 48-hour deadline he set to retract and apologise for the remarks. Ngeh said today he does not want this to go to court if possible as he only wanted to serve the people as the MP for Beruas. "I am giving Ismail a last chance. If he does not apologise, I will initiate legal action," he said. Ismail's comments drew flak from the public, opposition leaders and leaders within the Barisan Nasional component parties, with MCA, Gerakan and DAP members lodging police reports against him. -

Speech by DAP Secretary General Lim Guan Eng at the DAP

Speech by DAP Secretary General Lim Guan Eng at the DAP National Special Congress on 12 November 2017 at the IDCC Shah Alam, Selangor A Democratic, Progressive and Prosperous Malaysia for the many Preamble We, the DAP national delegates, gather here today for our National Special Congress as requested by the Registrar of Societies (ROS) to hold a fresh election for the Central Executive Committee members, once again. We had earlier decided to accept the instructions by the ROS, under protest. Since the last National Conference on 4th December 2016, we lost two of DAP’s most important national leaders, the former Secretary-General and my university mate Sdr. Kerk Kim Hock and the former Perak Chairman and one of the earliest DAP members Sdr. Lau Dak Kee. Both of them were detained under the Internal Security Act during the Ops Lalang in 1 987. Let us pay tribute to Sdr Kerk and Lau for their contributions to the Party and to Malaysia, especially during difficult dark years. 1. Crisis and leadership Before I proceed into the details of this special meeting, let us together express DAP’s solidarity with the people of Penang for the recent unprecedented natural disaster of worst flood and storm in history that befell upon us on 4th and 5th November. No words can fully grasp the unexpected calamity. On behalf of DAP, let me express my sincerest gratitude to Penangites and Malaysians that have helped our people during the tumultuous time, and those who continue to assist us till this very moment. Your precious assistance, contributions and donations will forever be appreciated. -

MALAYSIA Executive Summary The

MALAYSIA Executive Summary The constitution protects freedom of religion; however, portions of the constitution as well as other laws and policies placed some restrictions on religious freedom. The government did not demonstrate a trend toward either improvement or deterioration in respect for and protection of the right to religious freedom. The constitution gives the federal and state governments the power to “control or restrict the propagation of any religious doctrine or belief among persons professing the religion of Islam.” The constitution also defines ethnic Malays as Muslim. Muslims may not legally convert to another religion except in extremely rare circumstances, although members of other religions may convert to Islam. Officials at the federal and state government levels oversee Islamic religious activities, and sometimes influence the content of sermons, use mosques to convey political messages, and prevent certain imams from speaking at mosques. The approved form of Islam is Sunni Islam; other teachings and forms of Islam are illegal. The government maintains a dual legal system, whereby Sharia courts rule on religious, family, and some criminal issues involving Muslims and secular courts rule on other issues pertaining to both Muslims and the broader population. Government policies promoted Islam above other religions. Minority religious groups remained generally free to practice their beliefs; however, over the past several years, many have expressed concern that the secular civil and criminal court system has gradually ceded jurisdictional control to Sharia courts, particularly in areas of family law involving disputes between Muslims and non- Muslims. Religious minorities continued to face limitations on religious expression, including restrictions on the purchase and use of real property. -

Malaysia Daybreak | 22 July 2021 FBMKLCI Index

Malaysia | July 22, 2021 Key Metrics Malaysia Daybreak | 22 July 2021 FBMKLCI Index 1,700 ▌What’s on the Table… 1,650 ———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— 1,600 1,550 Axis REIT – Occupancy rates creeping up; a good sign 1,500 1H21 results were in line and was driven by contribution from new assets. Overall 1,450 positive operating indicators in 1H21 points to a resilient 2H21F, and should 1,400 mitigate the disruptions from the MCO and EMCO. A buying opportunity ahead of Jul-20 Sep-20 Nov-20 Jan-21 Mar-21 May-21 Jul-21 a recovery in 2H; Add call and TP maintained. ——————————————————————————— FBMKLCI 1,516.52 -3.45pts -0.23% JUL Future AUG Future ▌News of the Day… 1513.5 - (-0.43%) 1510.5 - (-0.46%) ———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— ——————————————————————————— Gainers Losers Unchanged • FMM hopes gov’t allows non-essential sectors to resume at 50% capacity 403 577 450 • MAHB in MoU with Skyports and Volocopter to study vertiport feasibility ——————————————————————————— • UMW Equipment optimistic of its growth prospects Turnover 5466.55m shares / RM3437.43m • 14m Sinovac doses to be sold to interested states, companies from this month 3m avg volume traded 6043.95m shares • Bursa seeking public feedback on listing requirements’ amendment 3m avg value traded RM3601.30m ——————————————————————————— • AirAsia Group seeks more time for private placement Regional Indices • Sapura Energy wins 7 contracts worth RM1.2bn FBMKLCI FSSTI JCI SET -

Primary Sources

It is not good enough to say, in declining jurisdiction, that allowing a Muslim to come out of Islam would "create chaos and confusion" or would "threaten public order". Those are not acceptable reasons. The civil courts have the jurisdiction to interpret New Straits Times (Malaysia) April 27, 2008 the Constitution and protect the fundamental liberties, including the right to freedom of religion under Article 11. Let's have certainty in this law That jurisdiction cannot be taken away by inference or implication, as seems to be the argument, but by an express enactment Raja Aziz Addruse (Former President of Bar Council and National Human Rights Council (Hakam)) which says that it is the intention of parliament to deprive the courts of their jurisdiction. The Kamariah case also highlights other aspects of our justice system. When she was convicted of apostasy, the syariah court judge had deferred her sentencing to KAMARIAH Ali, one of the followers of the Sky Kingdom sect led by Ayah Pin, was convicted of apostasy by the Terengganu March 3 to give her a chance to show that she had repented. In sentencing her to prison for two years, the judge said that he was Syariah Court on Feb 17, 2008. Her long and futile legal struggle highlights the need to seriously address the constitutional not convinced that she had repented because she had failed to respond when he greeted her with Assalamualaikum at the start of issue of the right of Muslims to freedom of religion. the court proceedings. The picture of a lonely woman who has been ostracised from society, being continually harassed to repent, offends our sense of justice and fair play. -

Dialogical Intersections of Tamil and Chinese Ethnic Identity in the Catholic Church of Peninsular Malaysia

ASIATIC, VOLUME 13, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 Dialogical Intersections of Tamil and Chinese Ethnic Identity in the Catholic Church of Peninsular Malaysia Shanthini Pillai,1 National University of Malaysia (UKM) Pauline Pooi Yin Leong,2 Sunway University Malaysia Melissa Shamini Perry,3 National University of Malaysia (UKM) Angeline Wong Wei Wei,4 Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), Malaysia Abstract The contemporary Malaysian Catholic church bears witness to the many bridges that connect ecclesial and ethnic spaces, as liturgical practices and cultural materiality of the Malaysian Catholic community often reflect the dialogic interactions between ethnic diversity and the core of traditional Roman Catholic practices. This essay presents key ethnographic data gathered from fieldwork conducted at selected churches in peninsular Malaysia as part of a research project that aimed to investigate transcultural adaptation in the intersections between Roman Catholic culture and ethnic Chinese and Tamil cultural elements. The discussion presents details of data gathered from churches that were part of the sample and especially reveal how ceremonial practices and material culture in many of these Malaysian Catholic churches revealed a high level of adaptation of ethnic identity and that these in turn are indicative of dialogue and mutual exchange between the repertoire of ethnic cultural customs and Roman Catholic religious practices. Keywords Malaysian Catholic Church, transcultural adaptation, heteroglossic Catholicism, dialogism, ethnic diversity, diaspora 1 Shanthini Pillai (Ph.D.) is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, National University of Malaysia (UKM). She held Research Fellowships at the University of Queensland, Australia and the Asia Research Institute, Singapore, and has published widely in the areas of her expertise.