Dfat Country Information Report Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malaysia 2019 Human Rights Report

MALAYSIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Malaysia is a federal constitutional monarchy. It has a parliamentary system of government selected through regular, multiparty elections and is headed by a prime minister. The king is the head of state, serves a largely ceremonial role, and has a five-year term. Sultan Muhammad V resigned as king on January 6 after serving two years; Sultan Abdullah succeeded him that month. The kingship rotates among the sultans of the nine states with hereditary rulers. In 2018 parliamentary elections, the opposition Pakatan Harapan coalition defeated the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition, resulting in the first transfer of power between coalitions since independence in 1957. Before and during the campaign, then opposition politicians and civil society organizations alleged electoral irregularities and systemic disadvantages for opposition groups due to lack of media access and malapportioned districts favoring the then ruling coalition. The Royal Malaysian Police maintain internal security and report to the Ministry of Home Affairs. State-level Islamic religious enforcement officers have authority to enforce some criminal aspects of sharia. Civilian authorities at times did not maintain effective control over security forces. Significant human rights issues included: reports of unlawful or arbitrary killings by the government or its agents; reports of torture; arbitrary detention; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy; reports of problems with -

Checklist for Passport Renewal

CHECKLIST FOR PASSPORT RENEWAL Important Notes: Applicant below 18 years old must be accompanied by either parent at our office. Children up to 4 years old are required to bring their own Passport photo. Children with dual nationalities (up to 16 years old) must provide Australian Declaratory Visa or Australian Passport (Original & 1 photocopy). DOCUMENTS REQUIRED QUANTITY 1 CURRENT PASSPORT Original ABOVE 18 YEARS OLD Original Applicant's Mykad 12 YEARS OLD - 18 YEARS OLD Applicant's MyKad Original 2 Both Parents' Mykad Original BELOW 12 YEARS OLD Original Applicant's Malaysian Birth Certificate / Borang W or H Original Parent’s MyKad VALID AUSTRALIAN VISA: Permanent Resident Visa Grant Notice Temporary Resident (min. 6 months validity required) Visa Grant Notice, AND 1 copy 3 Please provide additional documents as below; Letter of Employment / Employment Contract; OR Confirmation of Enrolment (CoE) & Student Card; OR Partner/Spouse/Sponsor Details; i.e Passport, Australian Visa, Marriage/Relationship Certificate We DO NOT ACCEPT VISITOR VISA for Passport renewal FEE: Accept Exact 4 AUD 80.00 AUD 40.00 (Below 12 years old & 60 years old and above) Cash ONLY PASSPORT APPLICATION FORM & PHOTO IS NOT REQUIRED; WE WILL DO LIVE FACIAL CAPTURE AT THE COUNTER. *Dark-coloured clothing covering shoulders and chest. CHECKLIST ON APPLICATION TO REPLACE LOST PASSPORT Important Notes: Application can be submitted in-person only and takes 5 working days to process. Passport that has been reported lost WILL BE CANCELLED IMMEDIATELY -

The Covid-19 Pandemic and Its Repercussions on the Malaysian Tourism Industry

Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, May-June 2021, Vol. 9, No. 3, 135-145 doi: 10.17265/2328-2169/2021.03.001 D D AV I D PUBLISHING The Covid-19 Pandemic and Its Repercussions on the Malaysian Tourism Industry Noriah Ramli, Majdah Zawawi International Islamic University Malaysia, Jalan Gombak, Malaysia The outbreak of the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) has hit the nation’s tourism sector hard. With the closure of borders, industry players should now realize that they cannot rely and focus too much on international receipts but should also give equal balance attention to local tourist and tourism products. Hence, urgent steps must be taken by the government to reduce the impact of this outbreak on the country’s economy, by introducing measures to boost domestic tourism and to satisfy the cravings of the tourism needs of the population. It is not an understatement that Malaysians often look for tourists’ destinations outside Malaysia for fun and adventure, ignoring the fact that Malaysia has a lot to offer to tourist in terms of sun, sea, culture, heritage, gastronomy, and adventure. National geography programs like “Tribal Chef” demonstrate how “experiential tourism” resonates with the young and adventurous, international and Malaysian alike. The main purpose of this paper is to give an insight about the effect of Covid-19 pandemic to the tourism and hospitality services industry in Malaysia. What is the immediate impact of Covid-19 pandemic on Malaysia’s tourism industry? What are the initiatives (stimulus package) taken by the Malaysian government in order to ensure tourism sustainability during Covid-19 pandemic? How to boost tourist confidence? How to revive Malaysia’s tourism industry? How local government agencies can help in promoting and coordinating domestic tourism? These are some of the questions which a response is provided in the paper. -

Relationship Between Literature & Politics in Selected Malay Novels

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 12, December, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2019 HRMARS Relationship between Literature & Politics in Selected Malay Novels Fatin Najla Binti Omar, Sim Chee Cheang To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i12/6826 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i12/6826 Received: 14 November 2019, Revised: 22 November 2019, Accepted: 15 December 2019 Published Online: 28 December 2019 In-Text Citation: (Omar & Cheang, 2019) To Cite this Article: Omar, F. N. B., & Cheang, S. C. (2019). Relationship between Literature & Politics in Selected Malay Novels. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(12), 905–914. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 9, No. 12, 2019, Pg. 905 - 914 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 905 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 12, December, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2019 HRMARS Relationship between Literature & Politics in Selected Malay Novels Fatin Najla Binti Omar, Sim Chee Cheang University Malaysia Sabah Abstract It cannot be denied that politics has a connection with the field of literature as politics is often a source of ideas and literature a "tool" to politicians especially in Malaysia. -

Lessons on Affirmative Action: a Comparative Study in South Africa, Malaysia and Canada

Lessons on affirmative action: a comparative study in South Africa, Malaysia and Canada Renata Pop ANR: 529152 Master Labour Law and Employment Relations Department of Labour Law and Social Policy Tilburg Law School Tilburg University Master’s Thesis supervisors: S.J. Rombouts Co-reader: S. Bekker Executive summary Creating equal opportunities and equity in the area of employment is a challenging policy decisions for all nations. In trying to address inequality in the labour market, some countries have chosen to adopt “positive discrimination” measures, otherwise referred to as affirmative action. Yet, years after their implementation, the measures are the target of enduring objections. Critics argue that the model provides unfair opportunities for a selected group, stressing market inequalities while supporters relentlessly point out the need for such measures in remedying past discrimination. In a first time, the study provides a set of definitions surrounding the measures as well as and overview of international and regional interpretations of affirmative action. Further arguments for and against the implementation are discussed. The second part of the research provides and in-depth analysis of how affirmative action is understood at national level in three different countries: Canada, South Africa and Malaysia. Having compared the three methods of implementation, the study analyses labour market changes incurred by the adoption of such policies in the three countries. The study finds more encouraging labour market results in Canada and Malaysia but denotes adverse spill over effects of these policies in all countries. The research notes that affirmative action measures have been necessary in addressing numerical representation issues. -

Forecasting Malaysian Ringgit: Before and After the Global Crisis

ASIAN ACADEMY of MANAGEMENT JOURNAL of ACCOUNTING and FINANCE AAMJAF, Vol. 9, No. 2, 157–175, 2013 FORECASTING MALAYSIAN RINGGIT: BEFORE AND AFTER THE GLOBAL CRISIS Chan Tze-Haw1, Lye Chun Teck2 and Hooy Chee-Wooi3 1 Graduate School of Business, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Pulau Pinang, Malaysia 2 Faculty of Business, Multimedia University, Jalan Ayer Keroh Lama, 75450 Ayer Keroh, Melaka, Malaysia 3 School of Management, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Pulau Pinang, Malaysia *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The forecasting of exchange rates remains a difficult task due to global crises and authority interventions. This study employs the monetary-portfolio balance exchange rate model and its unrestricted version in the analysis of Malaysian Ringgit during the post- Bretton Wood era (1991M1–2012M12), before and after the subprime crisis. We compare two Artificial Neural Network (ANN) estimation procedures (MLFN and GRNN) with the random walks (RW) and the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) methods. The out-of- sample forecasting assessment reveals the following. First, the unrestricted model has superior forecasting performance compared to the original model during the 24-month forecasting horizon. Second, the ANNs have outperformed both the RW and VAR forecasts in all cases. Third, the MLFNs consistently outperform the GRNNs in both exchange rate models in all evaluation criteria. Fourth, forecasting performance is weakened when the post-subprime crisis period was included. In brief, economic fundamentals are still vital in forecasting the Malaysian Ringgit, but the monetary mechanism may not sufficiently work through foreign exchange adjustments in the short run due to global uncertainties. These findings are beneficial for policy making, investment modelling, and corporate planning. -

Politik Dimalaysia Cidaip Banyak, Dan Disini Sangkat Empat Partai Politik

122 mUah Vol. 1, No.I Agustus 2001 POLITICO-ISLAMIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA IN 1999 By;Ibrahim Abu Bakar Abstrak Tulisan ini merupakan kajian singkat seJdtar isu politik Islam di Malaysia tahun 1999. Pada Nopember 1999, Malaysia menyelenggarakan pemilihan Federal dan Negara Bagian yang ke-10. Titik berat tulisan ini ada pada beberapa isupolitik Islamyang dipublikasikandi koran-koran Malaysia yang dilihat dari perspektifpartai-partaipolitik serta para pendukmgnya. Partai politik diMalaysia cidaip banyak, dan disini Sangkat empat partai politik yaitu: Organisasi Nasional Malaysia Bersatu (UMNO), Asosiasi Cina Ma laysia (MCA), Partai Islam Se-Malaysia (PMIP atau PAS) dan Partai Aksi Demokratis (DAP). UMNO dan MCA adalah partai yang berperan dalam Barisan Nasional (BA) atau FromNasional (NF). PASdan DAP adalah partai oposisipadaBarisanAltematif(BA) atau FromAltemattf(AF). PAS, UMNO, DAP dan MCA memilikipandangan tersendiri temang isu-isu politik Islam. Adanya isu-isu politik Islam itu pada dasamya tidak bisa dilepaskan dari latar belakang sosio-religius dan historis politik masyarakat Malaysia. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^^ ^ <•'«oJla 1^*- 4 ^ AjtLtiLl jS"y Smi]?jJI 1.^1 j yLl J J ,5j^I 'jiil tJ Vjillli J 01^. -71 i- -L-Jl cyUiLLl ^ JS3 i^LwSr1/i VjJ V^j' 0' V oljjlj-l PoUtico-Islnndc Issues bi Malays bi 1999 123 A. Preface This paper is a short discussion on politico-Islamic issues in Malaysia in 1999. In November 1999 Malaysia held her tenth federal and state elections. The paper focuses on some of the politico-Islamic issues which were pub lished in the Malaysian newsp^>ers from the perspectives of the political parties and their leaders or supporters. -

Islamic Revivalism and Democracy in Malaysia

University of Denver Undergraduate Research Journal Islamic Revivalism and Democracy in Malaysia Ashton Word1 and Ahmed Abd Rabou2 1Student Contributor, University of Denver, Denver, CO 2Advisor, Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, Denver, CO Abstract The paper examines democracy and secularism in Malaysia, a state rooted in Islam, and how it has been implemented in a country with a majority Muslim population. It briefly outlines how Islam was brought to the region and how British colonialism was able to implement secularism and democratic practices in such a way that religion was not wholeheartedly erased. Indeed, peaceful decolonization combined with a history of accommodating elites served to promote a newly independent Malaysia, to create a constitutional democracy which declares Islam as the religion of the Federation, and simultaneously religious freedom. Despite the constitution, the United Malays National Organization, UMNO, Malaysia’s ruling party for 61 years, managed to cap democracy through a variety of methods, including enraging ethnic tensions and checking electoral competitiveness. Growing public discontent from such actions resulted in Islamic Revivalist movements and increased Islamization at the expense of secular values. UMNO’s 2018 electoral loss to the Alliance of Hope party (PH) suggests a new commitment to democracy and reform, which if carried out, will likely result in a return to secular norms with Islamic elements that still maintain religious freedom rights and democratic practices that have, over the last two decades, been called into question. Keywords: Malaysia – democracy – Political Islam – secularism – modernity 1 INTRODUCTION dependent state that kept intact many of the demo- cratic processes and ideologies implemented under There exists a widespread belief that Islam and democ- colonial rule, specifically secularism. -

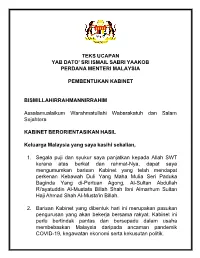

Teks-Ucapan-Pengumuman-Kabinet

TEKS UCAPAN YAB DATO’ SRI ISMAIL SABRI YAAKOB PERDANA MENTERI MALAYSIA PEMBENTUKAN KABINET BISMILLAHIRRAHMANNIRRAHIM Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh dan Salam Sejahtera KABINET BERORIENTASIKAN HASIL Keluarga Malaysia yang saya kasihi sekalian, 1. Segala puji dan syukur saya panjatkan kepada Allah SWT kerana atas berkat dan rahmat-Nya, dapat saya mengumumkan barisan Kabinet yang telah mendapat perkenan Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah Ibni Almarhum Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah Al-Musta'in Billah. 2. Barisan Kabinet yang dibentuk hari ini merupakan pasukan pengurusan yang akan bekerja bersama rakyat. Kabinet ini perlu bertindak pantas dan bersepadu dalam usaha membebaskan Malaysia daripada ancaman pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi serta kekusutan politik. 3. Umum mengetahui saya menerima kerajaan ini dalam keadaan seadanya. Justeru, pembentukan Kabinet ini merupakan satu formulasi semula berdasarkan situasi semasa, demi mengekalkan kestabilan dan meletakkan kepentingan serta keselamatan Keluarga Malaysia lebih daripada segala-galanya. 4. Saya akui bahawa kita sedang berada dalam keadaan yang getir akibat pandemik COVID-19, kegawatan ekonomi dan diburukkan lagi dengan ketidakstabilan politik negara. 5. Berdasarkan ramalan Pertubuhan Kesihatan Sedunia (WHO), kita akan hidup bersama COVID-19 sebagai endemik, yang bersifat kekal dan menjadi sebahagian daripada kehidupan manusia. 6. Dunia mencatatkan kemunculan Variant of Concern (VOC) yang lebih agresif dan rekod di seluruh dunia menunjukkan mereka yang telah divaksinasi masih boleh dijangkiti COVID- 19. 7. Oleh itu, kerajaan akan memperkasa Agenda Nasional Malaysia Sihat (ANMS) dalam mendidik Keluarga Malaysia untuk hidup bersama virus ini. Kita perlu terus mengawal segala risiko COVID-19 dan mengamalkan norma baharu dalam kehidupan seharian. -

SUHAKAM Laporan Tahunan 2019

LAPORAN TAHUNAN 2019SURUHANJAYA HAK ASASI MANUSIA Malaysia LAPORAN TAHUNAN 2019SURUHANJAYA HAK ASASI MANUSIA Malaysia CETAKAN PERTAMA, 2020 Hak cipta terpelihara Suruhanjaya Hak Asasi Manusia Malaysia (SUHAKAM) Kesemua atau mana-mana bahagian laporan ini boleh disalin dengan syarat pengakuan sumber dibuat atau kebenaran diperolehi daripada SUHAKAM. SUHAKAM menyangkal sebarang tanggungjawab, waranti dan liabiliti sama ada secara nyata atau tidak terhadap sebarang salinan penerbitan yang dibuat tanpa kebenaran SUHAKAM. Adalah perlu memaklumkan penggunaan. Diterbitkan di Malaysia oleh SURUHANJAYA HAK ASASI MANUSIA MALAYSIA (SUHAKAM) Tingkat 11, Menara TH Perdana 1001 Jalan Sultan Ismail 50250 Kuala Lumpur E-mel: [email protected] URL : http://www.suhakam.org.my Dicetak di Malaysia oleh Mihas Grafik Sdn Bhd No. 9, Jalan SR 4/19 Taman Serdang Raya 43300 Seri Kembangan Selangor Darul Ehsan Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Data Pengkatalogan Dalam Penerbitan ISSN: 2672 - 748X ANGGOTA SURUHANJAYA 2019 Dari kiri: Prof. Dato’ Noor Aziah Mohd. Awal (Pesuruhjaya Kanak-kanak), Dato’ Seri Mohd Hishamudin Md Yunus, Datuk Godfrey Gregory Joitol, Encik Jerald Joseph, Tan Sri Othman Hashim (Pengerusi), Dato’ Mah Weng Kwai, Datuk Lok Yim Pheng, Dr. Madeline Berma dan Prof. Madya Dr. Nik Salida Suhaila bt. Nik Saleh iv LAPORAN TAHUNAN 2019 KANDUNGAN PERUTUSAN PENGERUSI viii RUMUSAN EKSEKUTIF xvi BAB 1 MENERUSKAN MANDAT HAK ASASI MANUSIA 1.1 PENDIDIKAN DAN PROMOSI 2 1.2 KUASA MENASIHAT BERHUBUNG ASPEK 34 PERUNDANGAN DAN DASAR 1.3 ADUAN DAN PEMANTAUAN -

(“Bumiputera”) Malay Entrepreneurs in Malaysia

International Business and Management ISSN 1923-841X [PRINT] Vol. 2, No. 1. 2011, pp. 86-99 ISSN 1923-8428 [ONLINE] www.cscanada.net www.cscanada.org Indigenous (“Bumiputera”) Malay Entrepreneurs in Malaysia: Government Supports, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firms Performances Fakhrul Anwar Zainol1 Wan Norhayate Wan Daud2 Abstract: The research examines entrepreneurial orientation (EO) in Indigenous or Bumiputera entrepreneurs (Malay firms) by taking government supports as the antecedent. This construct is used to explain the influence of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and its consequence towards firm performance. Design/methodology/approach Multiples Linear Regressions (MLR) analysis was conducted to test the hypothesis on surveyed firms selected from the current available list given by MARA (the government agency for Indigenous or Bumiputera SMEs). The specific research question is: Does the relationship between government supports received by entrepreneur and firm performance is mediated by entrepreneurial orientation (EO)? Findings In Malay firms, the relationship between government supports with firm performance was not mediates by entrepreneurial orientation (EO). However, the construct is significant as predictor towards firm performance. Practical implications This research provides a better understanding of the indigenous entrepreneurs for policy makers, NGOs, business support organizations and the indigenous entrepreneurs themselves particularly in planning or utilizing government supports programmes. Originality/value The impact of government supports towards firm performance observed in Malay firms is unique to the paper. Our studies provided the empirical test in understanding indigenous entrepreneurship in Malay firms in Malaysia towards developing a more holistic entrepreneurship theory. Key words: Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO); Government Supports; Indigenous Entrepreneurship 1 Dr., Faculty of Business Management and Accountancy, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), 21300 Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu, Malaysia. -

Liberalism Between Acceptance and Rejection in Muslim World: a Review

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 11, November, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2019 HRMARS Liberalism between Acceptance and Rejection in Muslim World: A Review Mohd Safri Ali, Shahirah Abdu Rahim, Aman Daima Md Zain, Mohd Hasrul Shuhari, Wan Mohd Khairul Firdaus Wan Khairuldin, Mohd Sani Ismail, Mohd Fauzi Hamat To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i11/6600 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i11/6600 Received: 13 October 2019, Revised: 30 October 2019, Accepted: 03 November 2019 Published Online: 21 November 2019 In-Text Citation: (Ali et al, 2019) To Cite this Article: Ali, M. S., Rahim, S. A., Zain, A. D. M., Shuhari, M. H., Khairuldin, W. M. K. F. W., Ismail, M. S., Hamat, M. A. (2019). Liberalism between Acceptance and Rejection in Muslim World: A Review. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(11), 798–810. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 9, No. 11, 2019, Pg. 798 - 810 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 798 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol.