Hardesty Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wood River Area

Trail Report for the Sawtooth NRA **Early season expect snow above 8,000 feet high, high creek crossings and possible downed trees** Due to Covid 19 please be aware of closures, limits to number of people, and as always use leave no trace practices Wood River Area Maintained in Date Name Trail # Trail Segment Difficulty Distance Wilderness Area Hike, Bike, Motorized Description/Regulations Conditions, Hazards and General Notes on Trails 2020 Multi-use trail for hikers and bikers going from Sawtooth NRA to Galena 6/11/2020 Volunteers Harriman Easy 18 miles Hike and Bike Lodge; Interpretive signs along the trail; can be accessed along Hwy 75. Mountain Biked 9 miles up the trail. Easy- Hemingway-Boulders Hike, Bike only the 1st Wheelchair accessible for the first mile. Bicycles only allowed for the first 6/25/2020 210 Murdock Creek Moderate 7 miles RT Wilderness mile mile and then it becomes non-motorized in the wilderness area. Trail clear except for a few easily passible downed trees Hemingway-Boulders 127 East Fork North Fork Moderate 7 miles RT Wilderness Hike Moderate-rough road to trailhead. Hemingway-Boulders Drive to the end of the North Fork Road, hikes along the creak and 128 North Fork to Glassford Peak Moderate 4.5 Wilderness Hike through the trees, can go to West Pass or North Fork. North Fork Big Wood River/ West Moderate- Hemingway-Boulders Hike up to West Pass and connects with West Pass Creek on the East Fork Fallen tree suspended across trail is serious obstacle for horses one third mile 6/7/2020 Volunteers 115 Pass Difficult 6.3 Wilderness Hike of the Salmon River Road. -

1967, Al and Frances Randall and Ramona Hammerly

The Mountaineer I L � I The Mountaineer 1968 Cover photo: Mt. Baker from Table Mt. Bob and Ira Spring Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and April by The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington, 98111. Clubroom is at 719Y2 Pike Street, Seattle. Subscription price monthly Bulletin and Annual, $5.00 per year. The Mountaineers To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of North west America; To make expeditions into these regions m fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor life. EDITORIAL STAFF Betty Manning, Editor, Geraldine Chybinski, Margaret Fickeisen, Kay Oelhizer, Alice Thorn Material and photographs should be submitted to The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington 98111, before November 1, 1968, for consideration. Photographs must be 5x7 glossy prints, bearing caption and photographer's name on back. The Mountaineer Climbing Code A climbing party of three is the minimum, unless adequate support is available who have knowledge that the climb is in progress. On crevassed glaciers, two rope teams are recommended. Carry at all times the clothing, food and equipment necessary. Rope up on all exposed places and for all glacier travel. Keep the party together, and obey the leader or majority rule. Never climb beyond your ability and knowledge. -

Newsletter 2020

P R E S E R V I N G T H E P A S T . P R O T E C T I N G T H E F U T U R E . Sawtooth Interpretive & Historical Association A N N U A L N E W S L E T T E R 2 0 2 0 “I learn something every time I go into the mountains.” Michael Kennedy P R E S I D E N T ' S L E T T E R N O V E M B E R 2 0 2 0 Education, Preservation, and Interpretation are core values of the Sawtooth Interpretive & Historical Association. Our mission is ‘to protect and advance the natural and cultural history of Idaho’s Sawtooth-Salmon River Country through preservation and education.' 2020 has certainly been a year to move past. As we began planning for a robust season of operations, COVID-19 changed our course of action. Like for many, it was a challenging year. Thanks to the leadership of our Executive Director, Lin Gray, and our Kokanee spawning in Fishhook Creek by Jill Parker Lead Naturalist, Hannah Fake, along with our dedicated board members, we were able to strategically plan for operations this summer. Our leadership team took health and safety seriously and we emerged successfully with a modified approach to our typical programming. While income was down significantly in SIHA bookstores, we were able to welcome visitors to the Stanley Museum, Redfish Visitor Center & Gallery, spend more time engaging with the increased traffic at trailheads, and keep a sense of some normalcy with our Forum and Lecture Series. -

Hiking Trails

0a3 trail 0d4 trail 0d5 trail 0rdtr1 trail 14 mile connector trail 1906 trail 1a1 trail 1a2 trail 1a3 trail 1b1 trail 1c1 trail 1c2 trail 1c4 trail 1c5 trail 1f1 trail 1f2 trail 1g2 trail 1g3 trail 1g4 trail 1g5 trail 1r1 trail 1r2 trail 1r3 trail 1y1 trail 1y2 trail 1y4 trail 1y5 trail 1y7 trail 1y8 trail 1y9 trail 20 odd peak trail 201 alternate trail 25 mile creek trail 2b1 trail 2c1 trail 2c3 trail 2h1 trail 2h2 trail 2h4 trail 2h5 trail 2h6 trail 2h7 trail 2h8 trail 2h9 trail 2s1 trail 2s2 trail 2s3 trail 2s4 trail 2s6 trail 3c2 trail 3c3 trail 3c4 trail 3f1 trail 3f2 trail 3l1 trail 3l2 trail 3l3 trail 3l4 trail 3l6 trail 3l7 trail 3l9 trail 3m1 trail 3m2 trail 3m4 trail 3m5 trail 3m6 trail 3m7 trail 3p1 trail 3p2 trail 3p3 trail 3p4 trail 3p5 trail 3t1 trail 3t2 trail 3t3 trail 3u1 trail 3u2 trail 3u3 trail 3u4 trail 46 creek trail 4b4 trail 4c1 trail 4d1 trail 4d2 trail 4d3 trail 4e1 trail 4e2 trail 4e3 trail 4e4 trail 4f1 trail 4g2 trail 4g3 trail 4g4 trail 4g5 trail 4g6 trail 4m2 trail 4p1 trail 4r1 trail 4w1 trail 4w2 trail 4w3 trail 5b1 trail 5b2 trail 5e1 trail 5e3 trail 5e4 trail 5e6 trail 5e7 trail 5e8 trail 5e9 trail 5l2 trail 6a2 trail 6a3 trail 6a4 trail 6b1 trail 6b2 trail 6b4 trail 6c1 trail 6c2 trail 6c3 trail 6d1 trail 6d3 trail 6d5 trail 6d6 trail 6d7 trail 6d8 trail 6m3 trail 6m4 trail 6m7 trail 6y2 trail 6y4 trail 6y5 trail 6y6 trail 7g1 trail 7g2 trail 8b1 trail 8b2 trail 8b3 trail 8b4 trail 8b5 trail 8c1 trail 8c2 trail 8c4 trail 8c5 trail 8c6 trail 8c9 trail 8d2 trail 8g1 trail 8h1 trail 8h2 trail 8h3 trail -

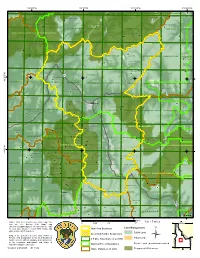

1:100,000 1 Inch = 1.6 Miles Central Idaho-01

R 10 E R 11 E 115°7'30"W R 12 E 115°W R 13 E 114°52'30"W R 14 E 114°45'W R 15 E 114°37'30"W R 16 E 114°30'W R 17 E 114°22'30"W R 18 E S k i k e l v e Joe Jump Basin e Lookout Mountain k La e e r st e r r k C k e R C e h ee r C e e Little a Cr u Iron Cre k nce C l h r w Airport Rd e Car c C Central Idaho-01 e bo n an k B liv o t C nat e l e d e r u k i a r C e a g l C e F S r r e e e e S e C a M M C k e t s r a k o in a C a G o Creek s th rc in k i o m o e C Fire Suppression Constraints e S re C r k y e r k e e C m re e ek n m C e k i r r Alpine Peak o Ziegler Basin t Fish Critical Habitats T 10 N a C Observation Peak J e an s B g je T 10 N n d i Jimmy Smith Lake n v i ulch Bull Trout Critical Habitat a G r Hoodoo Lake L k rry k Creek ake Cree he G Big L Big Lake Creek 222 e Lake C Grandjean e Big Balsam Rd r k Trailer Lakes Regan, Mount C e Spawning Areas of Concern Little Redfish Lake e ry r S a C ek 222 F re Trail Creek Lakes d o o C n c rk l u r Resource Avoidance Area 36 P i 36 o a ra Big Lake Creek a Williams Peak B M ye T NF-214 Rd tte 31 31 36 31 31 36 31 Ri Cleveland Creek Safety Concerns ve 36 Wapiti Creek Rd r EAST FORK 36 S a l Suppression tactics Avoidance Area 01 Thompson Peak m o Railroad Ridge n Crater Lake 06 01 R Bluett Creek D Misc Resource Areas i ry 06 01 k v 01 01 06 06 Gu 01 06 k e e lc e re h e C r k r k k e Meadows, The C e oo re Watson Peak im Creek x Wilderness Area e hh C Iron Basin J o r Fis old Chinese Wall ek F C G re ti C Bluett Creek i Slate Creek r Retardant Avoidance Area p Gunsight Lake e a ld W ou B -

1976 Bicentennial Mckinley South Buttress Expedition

THE MOUNTAINEER • Cover:Mowich Glacier Art Wolfe The Mountaineer EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Verna Ness, Editor; Herb Belanger, Don Brooks, Garth Ferber. Trudi Ferber, Bill French, Jr., Christa Lewis, Mariann Schmitt, Paul Seeman, Loretta Slater, Roseanne Stukel, Mary Jane Ware. Writing, graphics and photographs should be submitted to the Annual Editor, The Mountaineer, at the address below, before January 15, 1978 for consideration. Photographs should be black and white prints, at least 5 x 7 inches, with caption and photo grapher's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double· spaced, with at least 1 Y:z inch margins, and include writer's name, address and phone number. Graphics should have caption and artist's name on back. Manuscripts cannot be returned. Properly identified photographs and graphics will be returnedabout June. Copyright © 1977, The Mountaineers. Entered as second·class matter April8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Washington, under the act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly, except July, when semi-monthly, by The Mountaineers, 719 Pike Street,Seattle, Washington 98101. Subscription price, monthly bulletin and annual, $6.00 per year. ISBN 0-916890-52-X 2 THE MOUNTAINEERS PURPOSES To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanentform the history and tra ditions of thisregion; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of NorthwestAmerica; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all loversof outdoor life. 0 � . �·' ' :···_I·:_ Red Heather ' J BJ. Packard 3 The Mountaineer At FerryBasin B. -

§¨¦90 §¨¦90 Qr6

(! 117°20'0"W 117°0'0"W 116°40'0"W 116°20'0"W E Lancaster Rd "Spades Mountain 5 Hauser Lake 9 41 RQ y HAYDEN LAKE RATHDRUM NEWMAN LAKE HAYDEN w 3 t Avondale Lake SPADES MOUNTAIN 5 H CATARACT PEAK S E LALeMibBer gP PEeAakK y Hay d den " d Ave w N o d R H R McDonald Peak h Hayden Lake Echo Peak W R e a e Huckleberry Mountain r E Pra i irie y s d Ave lo " d e p " I v R d o u e a a t e d d R " 6 s 1 h 2 R N D G S West Canfield Butte R R k East Canfield Butte d t t c C m d s Tepee Peak r c h fie p Tresasure Mountain a l o R S t n d a " Lo e R e M e a l d N N r t " 6 t C a R t " B h o t n l 1 Monument Mountain Post Falls t F N " t A e F o r N 4 l e N u (! E t s M N S N elt a " t D " ic H Wolf Lodge Mountain e N k Wa N e y Kelly Mountain ve "c 90 N lo o Hemlock Mountain ¨¦§ p l E Riverv " Ro iew FERNAN LAKE ad m Dr 90 43 e N vw " 4 John Peak H " LIBERTY LAKE Skitwish Peak T 0 POST FALLS r ' COEUR D ALENE l " 0 Coeur d'Alene WOLF LODGE R SKITWISH PEAK BUMBLEBEE PEAK 4 d ° e Blossom Mountain !. -

Wood River Area

Trail Report for the Sawtooth NRA **Early season expect snow above 8,000 feet high, high creek crossings and possible downed trees** Due to Covid 19 please be aware of closures, limits to number of people, and as always use leave no trace practices Wood River Area Maintained in Date Name Trail # Trail Segment Difficulty Distance Wilderness Area Hike, Bike, Motorized Description/Regulations Conditions, Hazards and General Notes on Trails 2020 Multi-use trail for hikers and bikers going from Sawtooth NRA to Galena 6/11/2020 Volunteers Harriman Easy 18 miles Hike and Bike Lodge; Interpretive signs along the trail; can be accessed along Hwy 75. Mountain Biked 9 miles up the trail. Easy- Hemingway-Boulders Hike, Bike only the 1st Wheelchair accessible for the first mile. Bicycles only allowed for the first 6/25/2020 210 Murdock Creek Moderate 7 miles RT Wilderness mile mile and then it becomes non-motorized in the wilderness area. Trail clear except for a few easily passible downed trees Hemingway-Boulders 127 East Fork North Fork Moderate 7 miles RT Wilderness Hike Moderate-rough road to trailhead. Hemingway-Boulders Drive to the end of the North Fork Road, hikes along the creak and 128 North Fork to Glassford Peak Moderate 4.5 Wilderness Hike through the trees, can go to West Pass or North Fork. North Fork Big Wood River/ West Moderate- Hemingway-Boulders Hike up to West Pass and connects with West Pass Creek on the East Fork Fallen tree suspended across trail is serious obstacle for horses one third mile 6/7/2020 Volunteers 115 Pass Difficult 6.3 Wilderness Hike of the Salmon River Road. -

High Resolution Adobe PDF

115°20'0"W 115°0'0"W 114°40'0"W 114°20'0"W PISTOL LAKE CHINOOK MOUNTAIN R"ed Butte ARTILLERY DOME SLIDEROCK RIDGE FALCOGNroBusEeR CRreYek P PEeaAkK ROCK CREEK SHELDON PEAK WHITE GOAT MOUNTAIN LITTLE SOLDIER MOUNTAIN " Whi"te Valley Mountain Greyhound Mountain Parker Mountain " " Big Soldier Mountain Morehead Mountain Pinyon Peak White Mountain " " HONEYMOON LAKE " " BIG SOLDIER MOUNTAIN SOLDIER CREEK GREYHOUND MOUNTAIN PINYON PEAK CASTO SHERMAN PEAK CHALLIS CREEK LAKES TWIN PEAKS PATS CREEK FRANK CHURCH - RIVER OF NO RETURN WILDERNESS Sherman Peak Mayfield Peak Corkscrew Mountain " " " Langer Peak Blue Bunch Mountain Ruffneck Peak " " " Bear Valley Mountain " Estes Mountain " BLUE BUNCH MOUNTAIN CAPE HORN LAKES LANGER PEAK KNAPP LAKES MOUNT JORDAN CUSTER ELEVENMILE CREEK BAYHORSE LAKE BAYHORSE Keysto"ne Mountain Ram"shorn Mountain Cape Horn Mountain Cabin Creek Peak Red Mountain Bald Mountain " " " " S A L M O N - C H A L L I S N F Bachelor Mountain " Bonanza Peak B"ald Mountain N " " Basin Butte 0 ' 0 21 Copper MountainQ " 2 R ° " 4 4 CACHE CREEK BULL TROUT POINT BANNER SUMMIT ELK MEADOW BASINP BotU"atTo TMEountain EAST BASIN CREEK SUNBEAM THOMPSON CREEK CLAYTON BALD MOUNTAIN Saturday Mountain Elk Mountain " " Red Mountain " McGown Peak Potaman Peak Stanley " " !( Robinson Bar Peak " Lookout Mountain EIGHTMILE MOUNTAIN " GRANDJEAN STANLEY LAKE STANLEY Eightmile Mountain Observation PeakAlpine Peak CASINO LAKES ROBINSON BAR LIVINGSTON CREEK POTAMAN PEAK ZIEGLER BASIN " " " Williams Peak Thompson Pea"k " Watson Peak " Horstmann Peak Baron -

Wood River Area

Trail Report for the Sawtooth NRA Please use leave no trace practices Conditions are always changing on the Forest Wood River Area Hike, Bike, Horseback Date Name Trail # Trail Segment Difficulty Distance Wilderness Area Riding, and/or Description/Regulations Maintained in Conditions, Hazards and General Notes on Trails Motorized 2021 Harriman Easy 18 miles Hike and Bike Multi-use trail for hikers and bikers going from Sawtooth NRA to Galena Lodge; Interpretive signs along the trail; can be accessed along Hwy 75. 210 Murdock Creek Easy- 7 miles RT Hemingway-Boulders Hike Wheelchair accessible for the first mile. This is a great area for bird Moderate Wilderness watching and a nice stroll through the trees along the creek. And if you want to just turn around when it starts to go uphill it makes a nice easy hike, but then it starts to go uphill and opens up to nice views and becomes moderate. 127 East Fork North Fork Moderate 7 miles RT Hemingway-Boulders Hike Moderate-rough road to trailhead. Wilderness 128 North Fork to Glassford Peak Moderate 4.5 Hemingway-Boulders Hike Drive to the end of the North Fork Road, hikes along the creak and Wilderness through the trees, can go to West Pass or North Fork. 115 North Fork Big Wood River/ West Moderate- 6.3 Hemingway-Boulders Hike Hike up to West Pass and connects with West Pass Creek on the East Fork Pass Difficult Wilderness of the Salmon River Road. Hazardous for horses. 129 West Fork Moderate- 3 Hemingway-Boulders Hike Trail finding can be a challenge at the trailhead. -

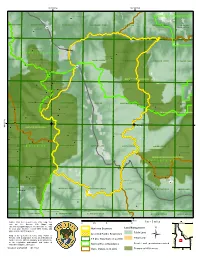

High Resolution Adobe PDF

115°0'0"W 114°40'0"W Potato Mountain " BANNER SUMMIT ELK MEADOW BASIN BUTTE EAST BASIN CREEK SUNBEAM THOMPSON CREEK CLAYTON Saturday Mountain Elk Mountain Q21 R " " McGown Peak " Stanley !( Robinson Bar Peak S A L M O N - C H A L L I S N F " Lookout Mountain " GRANDJEAN STANLEY LAKE STANLEY CASINO LAKES ROBINSON BAR LIVINGSTON CREEK POTAMAN PEAK Observation Peak Alpine Peak " " RQ75 Williams Peak " Thompson Peak " WHITE" WCaLtsOonU PDeSa kWILDERNESS Baron Peak Grandjean Peak H"orstmann Peak " " Heyburn Mountain Lee Peak " " Tohobit Peak Braxon Peak " " Warbonnet Peak " Cony Peak EDAHO MOUNTAIN " WARBONNET PEAK " MOUNT CRAMER Packrat Peak OBSIDIAN WASHINGTON PEAK BOULDER CHAIN LAKES BOWERY CREEK Black"man Peak Merriam Peak Patterson Peak Decker Peak " Bugle Mountain " " Reward Peak " Castle Peak " " Elk Peak Sexy PeakSevy Peak JIM MCCLURE-JERRY PEAK WILDERNESS Pinchot Mountain " " " Washington Peak N Edaho Mountain " " 0 " ' 0 Bible Back Mountain ° Payette Peak 4 Smoky Peak Cro"esus "Peak 4 " " SAWTOOTH WILDERNESS Blacknose Mountain " Parks Peak Horton Peak " " Tackobe Mountain Glens Peak " Plummer Peak " McDonald Peak " " MOUNT EVERLY Snowyside Peak NAHNEKE MOUNTAIN " Browns P"eak SNOWYSIDE PEAK ALTURAS LAKE B O I S E N F HORTON PEAK GALENA PEAK RYAN PEAK Flat Top Mountain " Glassford Peak " Nahneke Mountain HEMINGWAY-BOULDERS WILDERNESS Mattingly Peak " " S A GWalenaT PeaOk O T H N F " Blizzard Mountain " Easley Peak Greylock Mountain " Silver Peak " Grey Lock Peak " " Bromaghin Peak Boulder Peak " " ATLANTA WEST ATLANTA EAST MARSHALL PEAK FRENCHMAN CREEK GALENA EASLEY HOT SPRINGS AMBER LAKES Atlanta !( Marshall Peak " Norton Peak " Two Point Mountain Paradise Peak CAYUSE POINT " " ROSS PEAK NEWMAN PEAK PARADISE PEAK BAKER PEAK BOYLE MOUNTAIN GRIFFIN BUTTE " Miles 1 in = 5 miles NOTE: This is a georeference PDF map. -

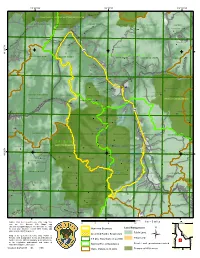

High Resolution Adobe PDF

115°20'0"W 115°0'0"W 114°40'0"W Bear Valley Mounta"in d R k Beaver Cree Estes Mountain FRANK CHURCH - RIVER OF NO RETURN WILDERNESS " BLUE BUNCH MOUNTAIN LANGER PEAK CAPE HORN LAKES KNAPP LAKES MOUNT JORDAN CUSTER Cabin Creek Peak Cape Horn Mountain Cape Horn Lake #1 d L R Red Mountain o ek " o Bald Mountain d d " e Rd " n R R r tain k C C oun C r 2 a p " o 8 p p M r F e a e e 5 n d ke e n d H K e a a o k Y o r R n R R Luc R d ky B p d oy lo Rd e 1 v B 2 e ear Va Bachelor Mo"untain D lley R y t d w 5 s H 19 Bonanza Peak re d o e F t R " a fs tl t s N a S U " N Basin Butte 0 ' 0 " 2 ° Copper Mountain 21 4 RQ " 4 CACHE CREEK S A L M O N - C H A L L I S N F BULL TROUT POINT BANNER SUMMIT ELK MEADOW BASIN BUTPToEtato Mountain EAST BASIN CREEK d " SUNBEAM R k Bull Trout Lake e B e Rd a r k s N ee C fr Cr in 6 elly C h 29 K ree c k R a Elk Mountain d e J P " oe s G Red Mountain u lc " h J e e Stanley Lake 75 p d y R R ek w d Cre H ed te ok a Cro t McGown Peak S " Stanley d !( Robinson Bar Peak ek R Cre Iron " Lookout Mountain EIGHTMILE MOUNTAIN " GRANDJEAN STANLEY LAKE STANLEY CASINO LAKES ROBINSON BAR Eightmile Mountain orest Develo atl F p WHITE CLOUDS WILDERNESS " te N Ro Obse"rvationS aPweatokoAtlhp iLnea kP"ee #a1k ou ad Goat Lake #1 R 524 ic Rd n Williams Peak Little Redfish Lake ce S " e in Thompson Peak P a " os y r 75 a e RQ Watson Peak n d W o P " a Baron Peak d l i Grandjean Peak H"orstmann Peak H " " Redfish Lake Heyburn Mountain N Lee Peak a t Braxon" Peak l " Picket Mountain Tohobit Peak F " o " " r Jackson Peak e s " t Baron