1 Long-Distance Walking Tracks: Offering Regional Tourism in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CW Adventure Word Template

Our Self-Guided Walking Adventures are ideal for travelers with an independent spirit who enjoy exploring at their own pace. We provide authentic accommodations, luggage transfers, and some meals, along with comprehensive Route Notes, detailed maps, and 24-hour emergency assistance. This gives you the freedom to focus on the things that matter to you—no group, no guide, and no set schedule to stand in the way of enjoying your adventure, your way. The wild coast of Australia’s state of Victoria has long been hidden from view, an unspoiled green ribbon of rolling hills sandwiched between the scenic Great Ocean Road and the tempestuous surf of the Southern Ocean. Today, walkers can finally experience the primitive and pristine beauty of this staggeringly beautiful corner of Great Otway National Park, thanks to the recently completed Great Ocean Walk. Lace up your boots to explore almost 60 miles of untouched wilderness, choosing high trails over towering sea cliffs or beach hikes alongside crashing surf. From the charming village of Apollo Bay to the famed Twelve Apostles sea stacks, this is some of the most remote and remarkable terrain you are ever likely to traverse. Using rustic, homestead-style lodgings in sparsely populated seaside towns as your base, you hike through primeval manna gum forests where koalas linger high in the canopy and past wide grassland grazed by kangaroos. Trace heathland ablaze with vibrant wildflowers and lush wetlands where rivers and waterfalls meet the sea. Marvel at colossal shipwrecked anchors cemented in beach sand and stroll through working farmlands. But perhaps the real beauty of hiking the undulating Great Ocean Walk is this: few people have walked it before you, and it is pure privilege to count yourself among the first to witness its magnificence. -

Great Ocean Road and Scenic Environs National Heritage List

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Historic Item: 1 Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: Great Ocean Road and Rural Environs Other Names: Place ID: 105875 File No: 2/01/140/0020 Primary Nominator: 2211 Geelong Environment Council Inc. Nomination Date: 11/09/2005 Principal Group: Monuments and Memorials Status Legal Status: 14/09/2005 - Nominated place Admin Status: 22/08/2007 - Included in FPAL - under assessment by AHC Assessment Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: : Location Nearest Town: Apollo Bay Distance from town (km): Direction from town: Area (ha): 42000 Address: Great Ocean Rd, Apollo Bay, VIC, 3221 LGA: Surf Coast Shire VIC Colac - Otway Shire VIC Corangamite Shire VIC Location/Boundaries: About 10,040ha, between Torquay and Allansford, comprising the following: 1. The Great Ocean Road extending from its intersection with the Princes Highway in the west to its intersection with Spring Creek at Torquay. The area comprises all that part of Great Ocean Road classified as Road Zone Category 1. 2. Bells Boulevarde from its intersection with Great Ocean Road in the north to its intersection with Bones Road in the south, then easterly via Bones Road to its intersection with Bells Beach Road. The area comprises the whole of the road reserves. 3. Bells Beach Surfing Recreation Reserve, comprising the whole of the area entered in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) No H2032. 4. Jarosite Road from its intersection with Great Ocean Road in the west to its intersection with Bells Beach Road in the east. -

Great Ocean Walk Guided Tour

GREAT OCEAN WALK GUIDED TOUR AllTrails Tours - The Great Ocean Road Slow Travel Tour Specialists This is a 7-day walk along the entire length of the Great Ocean Walk, with no missing sections, at an enjoyable pace. Each day you will enjoy this world class walking track and rejuvenate nightly with hot showers and the conveniences of modern accommodation - perhaps even a massage and a few drinks before a quality dinner. AllTrails has been taking groups for multi-day tours around Australia for over 20 years and have extensive experience in the Great Ocean Road region. We now apply our winning AllTrails formula to the famous Great Ocean Walk journey: top accommodation (no lodge accommodation or shared facilities), quality restaurant meals (even some of the lunches), luggage transfers (no carrying a pack), massage therapist (staff), full guide support and that famous AllTrails camaraderie. AllTrails creates bespoke tours for the discerning traveller - unique, individual experiences where we are as excited to be on tour as you are. The Tour at a Glance Duration: 7 days / 6 nights Distance: 104 km Average Daily: 14km (shorter options available) Group Size: 10-15 approx Accommodation: Quality ensuite accom all the way Trail snacks: Included Meals: All meals included Deposit: $400pp Surface: Well compacted walking tracks, some steps/stairs Terrain: Undulating coastal tracks with some hilly sections Staff: Walking guide, vehicle support, massage therapist Difficulty Rating: Generally easy to moderate (occasional harder sections) Current dates available 10-16 Sep 2020* and 6-12 Apr 2021 * New date of departure, amended from 10 Sep due to COVID-19 Always wanted to walk the full length of the Great Ocean Walk? This is the Great Ocean Walk without the logistical headaches – we organise everything that you will need including quality accommodation, food, vehicle support, safety briefings, first-aid qualified guides, massage therapist, luggage transfer, great camaraderie and much more. -

The Great Ocean Walk

The Great Ocean Walk This tour hikes the stunning Great Ocean Walk trail, from the quaint town of Apollo Bay finishing at the iconic Twelve Apostles. It is the ultimate guided tour with a relaxed pace, luxury accommodation and fabulous food and wine. The hiking is wonderfully varied and includes an amazing variety of coastal environments with a diverse array of flora and fauna - towering gum trees, deserted beaches and fertile farmland. The fabulous hiking is enhanced by the compelling history of Victoria’s Shipwreck Coast. Cost: $3150 per person based on a twin-share Single supplement $300* * Depending on the make-up of the group single travellers may be required to share a bathroom, but not a bedroom. What's Included? • Mick and Jackie Parsons as your experienced and knowledgeable guides who will look after your every need and bring this stunning area to life • 2 nights in luxury bed and breakfast accommodation in Apollo Bay (Captains on the Bay) • 3 nights in luxury cottage-style accommodation mid-trail (Southern Anchorage Retreat). Cottages have one or two bedrooms. All bedrooms have ensuite facilities. Each cottage has a Jacuzzi. Ample breakfast provisions provided in the cottages. • 1 night in boutique accommodation in Port Campbell • All meals including quality local wines • Gourmet picnic lunches each day, snacks en route, drinks at end of hike • Delicious dinners: In Apollo Bay we eat in two excellent local restaurants including the award-winning Chris’s restaurant. At Southern Anchorage the in-house dinners are prepared by Mick, a qualified chef, and matched to wonderful local wines. -

The Great Ocean Road Where Nature’S Drama Unfolds at Every Turn

The Great Ocean Road Where nature’s drama unfolds at every turn. The raw energy of the Great Southern Ocean meets a spectacular landscape to create awe inspiring scenery and a vast array of ever changing landscapes, communities, habitats and wildlife that will captivate and invigorate. GeoloGy in real time from special viewing platforms just after the sun goes down. Offshore islands provide a home for the critically Limestone layers have eroded at different rates to create endangered orange-bellied parrot. tunnels and caves as well as spectacular natural structures like the Twelve Apostles and the Loch Ard Gorge. Erosion occurs at a rapid rate as the awesome power of the sea a livinG oCean pounds the earth — collapsing one of the Twelve Apostles in 2005 and tumbling the London Bridge rock formation Beneath the ocean surface lies an explosion of life — 85 per into the sea in 1990. cent of species found in the waters here are found nowhere else on earth. Deep sea and reef fish, sharks, dolphins, octopus, sea Coastal landsCapes dragons and the Australian fur seal all inhabit the area. The breathtaking cliff faces of the Great Ocean Road fall Offshore reefs 30 to 60 metres underwater are home to away to a spectacular marine environment. The intertidal brilliant sponge gardens and kelp forests where fish and zone supports a vast array of crabs, molluscs, fish, seaweed other aquatic species such as sea dragons, sea slugs and and algae as well as fantastic bird life. sea stars make their homes. The diversity and abundance of marine wildlife has significantly increased since the Over 170 bird species can be seen throughout the introduction of a marine reserve system in 2002. -

Questions and Answers Plus These Additional Planning Tools Will Ensure You Have a Safe, Enjoyable and Inspiring Experience

www.greatoceanwalk.com.au Plan for a safe, unforgettable experience on the Great Ocean Walk QUESTIONS & ANSWERS April, 2018 Things you need to know 1 Great Ocean Walk, Australia – the Great Ocean Road, Australian Wildlife and the iconic Twelve Apostles are all attributes of this spectacular eight-day, one direction, long-distance walk covering approximately 110km. The Great Ocean Walk extends from the Apollo Bay Visitor Information Centre through the Great Otway and Port Campbell National Parks and concludes at the iconic Twelve Apostles near Port Campbell. Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk. The Great Ocean Walk weaves its way through tall forests and coastal heathlands, beside rocky shore platforms, crossing creeks and rivers, passing above wild-rocky shores and deserted beaches with panoramic views from windswept cliff-tops. Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk. Nature unfolds at every step on the Great Ocean Walk - located on the edge of the Southern Ocean and truly in the hands of nature. Great Ocean Walk’s most frequently asked Questions and Answers plus these additional planning tools will ensure you have a safe, enjoyable and inspiring experience. Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk, Great Ocean Walk OFFICIAL MAP: Information Guide and Map Edition 5 to the Great Ocean Walk (new) OFFICIAL WALKERS MAP-BOOKLET: Easy to use ring-bound maps in half-day page view format OFFICIAL WEBSITE: www.greatoceanwalk.com.au 1. MAP & BOOKLET: The official ‘Information Guide and Map Edition 6 to the Great Ocean Walk’ ................ -

Fitzgerald River National Park Coastal Walk Trail

Fitzgerald River National Park Coastal Walk Trail Department of Environment and Conservation COPYRIGHT STATEMENT FOR: Fitzgerald River National Park Coastal Walk Trail 7238-2444-10R Copyright © General Conditions of Contract for Government Contracts Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), the whole or any part of this report may not be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owner, the Department of Environment and Conservation. This includes microcopying, photocopying or recording of any parts of the report. Neither may the information contained in this report be reproduced, transmitted or stored electronically in any form, such as in a retrieval system, without the specific written permission of the Department of Environment and Conservation. Direct all inquiries to: Ecoscape (Australia) Pty Ltd PO Box 50 / 9 Stirling Hwy North Fremantle WA 6159 ph: (08) 9430 8955 fax: (08) 9430 8977 Fitzgerald River National Park Coastal Walk Trail Walk Coastal Park National River Fitzgerald ii Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ..................................................v 2.0 Introduction .............................................................1 2.1 Key Issues................................................................................. 1 3.0 Site Appreciation ......................................................5 3.1 Socio-cultural Analysis ........................................................... 5 3.2 Biophysical Analysis .................................................................6 -

From Walking Trails to Hidden Forest Retreats, the Otways Is a Place For

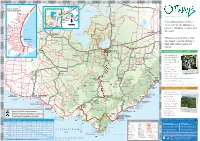

1 AB GFEDC HI UTSRQPONMLKJ LOCATION WITHIN REGION 3 MELBOURNE M1 3 APOLLO BAY FWY TOWNSHIP MAP M1 PRINCES GEELONG A1 4 A1 Queenscliff 4 Ferry Walks & Waterfalls Map Colac Torquay Anglesea From walking trails to hidden Lavers Lorne N 5 100 20 km30 5 Port Hill forest retreats, the Otways is a Campbell Apollo Bay place for adventure, romance and 6 6 discovery. 7 Lake 7 Whether you go inland or hug Corangamite Lookout the rugged coast, the Otways is filled with natural beauty and TO GEELONG VIA MORIAC 8 8 history. WALKS & WATERFALLS LOOP 9 9 This stunning loop drive takes in Apollo Bay, Cape Otway, 10 10 Lavers Hill, and Beech Forest. Possible stops include 11 11 the Cape Otway Lightstation, Great Hopetoun Falls Otway National Park, 12 12 Otway Fly Treetop Adventures, waterfalls, a Californian Redwood Forest and rainforest walks. LEAFLET AMENDED 26/04/16 @ 3.30pm. 13 13 For all our walks please see the other side of this map! UPPER GELLIBRAND RD VOLCANIC PLAINS LOOP 14 14 The area north of Bay of Martyrs Colac is famous for its volcanic past. 15 15 Visit both east and F O R western lookouts at ORS-PLOBYRD BAY FORREST-APOLLO R E S T - A P Red Rock to view the O L LO B vast volcanic plains, A 16 Y 16 R D dormant craters and Volcanic Plains www.kanawinkageopark.org.au • Drive on Left Side of the road in Australia crater lakes of 17 • For Bushfire Information please see www.cfa.com.au 17 Kanawinka world • We do not recommend using a GPS device when you listed Geopark. -

Your Trip Information

MELBOURNE | ESSENTIALS Your Trip Information We’ve partnered with Tasmanian Walking Company to provide your trip of a lifetime! To help you prepare for this trip, we’ve gathered some useful information together. Some things, such as flights and insurance will be relevant sooner; and some things such as gear will be relevant closer to departure Before your trip Visas for New Zealanders You’ve booked! New Zealand citizens don’t need to apply for a visa before coming to Australia What’s next? however NZ permanent residents will need to apply for a visa. For more information please head here: newzealand.embassy.gov.au Within a week of booking: pay deposit, confirm your contract and Travel Insurance log into your booking As an Active Adventures Australia traveller, you’re required to have travel Sooner rather than later: check insurance for your trip – please be aware some insurance companies require passport, arrange travel insurance insurance to be purchased within 14 days of deposit payment (to be eligible for and book your flights, start your pre-exisitng medical cover). training regime and get fit! We highly recommend World Nomads as they offer competitive travel Three months before your trip: insurance policies that suit our type of travel with the minimum requirements for full payment is due, complete extra emergency repatriation, medical insurance as well as trip cancellation cover. items* Travel agencies Four weeks before your trip: check We recommend booking your flights through our preferred travel partner, for any missing details for your trip. Fuzion Travel. They’re our experienced hand-picked experts in travel, passionate Two weeks before your trip: about what they do, and will tailor-make your flight itinerary to match your reconfirm your flights, print your Active Adventures tour. -

Great Ocean Road World Class Tourism Investment Study

[TYPE TEXT] Great Ocean Road World Class Tourism Investment Study A Product Gap Audit Investment and Regulatory Reform Working Group [TYPE TEXT] GREAT OCEAN ROAD WORLD CLASS TOURISM INVESTMENT STUDY A Product Gap Audit Investment and Regulatory Reform Working Group Author Mike Ruzzene Contributors Kate Bailey Jo Jo Chen Shashi Karunanethy Reviewed by Matt Ainsaar © Copyright, Urban Enterprise Pty Ltd, September 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under Copyright Act 1963, no part may be reproduced without written permission of Urban Enterprise Pty Ltd. Document Information Filename: Great Ocean Road Product Audit Draft Report 4th October 2011 Last Saved: 26 November 2011 6:09 PM Last Printed: 26 November 2011 6:09 PM File Size: 8179 kb Disclaimer Neither Urban Enterprise Pty. Ltd. nor any member or employee of Urban Enterprise Pty. Ltd. takes responsibility in any way whatsoever to any person or organisation (other than that for which this report has been prepared) in respect of the information set out in this report, including any errors or omissions therein. In the course of our preparation of this report, projections have been prepared on the basis of assumptions and methodology which have been described in the report. It is possible that some of the assumptions underlying the projections may change. Nevertheless, the professional judgement of the members and employees of Urban Enterprise Pty. Ltd. have been applied in making these assumptions, such that they constitute an understandable basis for estimates and projections. Beyond this, to the extent that the assumptions do not materialise, the estimates and projections of achievable results may vary. -

The Apollo Bay Trail Evi Janse De Jonge

The Apollo Bay Trail Evi Janse de Jonge Student no: 29968895, UPD4002 The Ecological City, Monash University Summary Introduction construction of a trail between Skenes The Great Ocean Road celebrates its Creek and Fairhaven. Skenes Creek 100 year anniversary this year. The 243 The proposed shared walking and cycling kilometre road was constructed along trail aims for the following outcomes: the Victorian coastline by World War I returning soldiers and is therefore the 1. Connectivity largest War Memorial in the world. The road connected the once isolated towns, • Connect Great Ocean Walk with Skenes which are now crowded by tourists. Last Creek to Fairhaven trail year, more than 6 million people drove • Connect Apollo Bay town centre with Apollo Bay the scenic drive.1 This immensive tourism foreshore and existing trails puts its pressure on the region. Besides, • Improve signage and route of the Great climate change impacts the area heavily Ocean Walk Image 1: Proposed connection between and is expected to do so even more in the • Make the harbour easier to find and Marengo near future. At various points, the road is accessible for tourists and community Great Ocean Walk (south) and currently damaged by landslides and sanddunes investigated trail erode quickly. 2. Resilience between Skenes N Creek and Fairhaven This project focuses on Apollo Bay and its • The trail is constructed with (north). surrounding area within the Great Ocean sustainable, locally produced material Road region. Approximately 1600 people • At certain points along the beach, the live permanently in this coastal town. The trail can serve as a seawall to prevent town experiences dramatic beach erosion the beach and dunes from erosion (image 2) and some areas are subject to • At other points, the trail will be elevated flooding. -

Australia Women's Adventure: Melbourne & the Great Ocean Road

Australia Women's Adventure: Melbourne & the Great Ocean Road 8 Days Australia Women's Adventure: Melbourne & the Great Ocean Road Take this walk-of-a-lifetime along the Great Ocean Road — MT Sobek's first women's trip Down Under! After meeting your fellow walkers and touring Melbourne's defining Yarra River, embark on a six-day adventure along the 62-mile Great Ocean Walk, with spectacular scenery and unparalleled coastal views. Traverse cliff tops, native forests, and bucolic heathland on your way to windswept beaches, sunken wrecks, and postcard-perfect lookouts. The jewel in the trip's crown? Beholding the iconic 12 Apostles — from land and air! Details Testimonials Arrive: Melbourne, Australia “I have taken 12 trips with MT Sobek. Each has left a positive imprint on me—widening my view of the Depart: Melbourne, Australia world and its peoples.” Jane B. Duration: 8 Days Group Size: 6-14 Guests “I have traveled extensively around the world. The experience with MT Sobek was by far the best I have Minimum Age: 14 Years Old ever had. Thank you for such excellence.” Marianne W. Activity Level: . REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek has been exploring the This unique women's adventure Traverse areas of historical Pacific for over 20 years, working includes up to 45 miles of and cultural significance, and with the best local guides for an Australia's iconic Great Ocean Walk. blend fun days on the trail with immersive and fun experiences. relaxed evenings at top hotels. ACTIVITIES LODGING CLIMATE Moderate to strenuous daily Estate retreats and comfortable Summers in southeast Australia can hikes between 5 and 11 miles, inns, plus three nights at be hot with mild nights.