Teaching Shakespeare to ESL Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan by Ya-hui Huang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire Jan 2012 Abstract Since the 1980s, Taiwan has been subjected to heavy foreign and global influences, leading to a marked erosion of its traditional cultural forms. Indigenous traditions have had to struggle to hold their own and to strike out into new territory, adopt or adapt to Western models. For most theatres in Taiwan, Shakespeare has inevitably served as a model to be imitated and a touchstone of quality. Such Taiwanese Shakespeare performances prove to be much more than merely a combination of Shakespeare and Taiwan, constituting a new fusion which shows Taiwan as hospitable to foreign influences and unafraid to modify them for its own purposes. Nonetheless, Shakespeare performances in contemporary Taiwan are not only a demonstration of hybridity of Westernisation but also Sinification influences. Since the 1945 Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT) takeover of Taiwan, the KMT’s one-party state has established Chinese identity over a Taiwan identity by imposing cultural assimilation through such practices as the Mandarin-only policy during the Chinese Cultural Renaissance in Taiwan. Both Taiwan and Mainland China are on the margin of a “metropolitan bank of Shakespeare knowledge” (Orkin, 2005, p. 1), but it is this negotiation of identity that makes the Taiwanese interpretation of Shakespeare much different from that of a Mainlanders’ approach, while they share certain commonalities that inextricably link them. This study thus examines the interrelation between Taiwan and Mainland China operatic cultural forms and how negotiation of their different identities constitutes a singular different Taiwanese Shakespeare from Chinese Shakespeare. -

Henry V to China: to Beijing, Announce That Paapa Essiedu Will Play the Title Role

MEMBERSSEPTEMBER 2015 ’NEWSFULL MEMBER NEW RSC FULL MEMBERS’ TICKET HOTLINE 01789 403458 BOOK ONLINE OR VISIT EXCLUSIVE MEMBERS’ PAGES AT www.rsc.org.uk/membership TO HE WAS NOT OF AN AGE, BUT FOR ALL TIME! MEMBERS' PRIORITY BOOKING DATES FOR STRATFORD-UPON-AVON AND LONDON BARBICAN FULL MEMBERS' WEB AND TELEPHONE BOOKING OPENS MONDAY 21 SEPTEMBER 2015 ASSOCIATE MEMBERS' WEB AND TELEPHONE BOOKING OPENS MONDAY 5 OCTOBER 2015 PUBLIC BOOKING OPENS MONDAY 19 OCTOBER 2015 GREGORY DORAN – RSC ARTISTIC DIRECTOR 2016 is a remarkable SUMMER 2016 BEYOND STRATFORD year. It is 400 years Simon Godwin (The Two Gentlemen of Verona 2014) From an international perspective, we will tour since the death of will direct Hamlet and we are very excited to Henry IV and Henry V to China: to Beijing, announce that Paapa Essiedu will play the title role. Shanghai and Hong Kong, and then the full cycle William Shakespeare, Paapa played Fenton in our most recent The Merry to the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York for Wives of Windsor and a stunning Romeo at the Shakespeare’s Birthday. We have a very special our house playwright. Tobacco Factory in Bristol earlier this year. relationship with America and it is fitting to be So we want to There has not been a production of Cymbeline on celebrating with our American supporters next year. the main stage for many years. Working through encourage everybody the canon over the next few years allows us to give to visit us in his home weight and scale to lesser known Shakespeare plays. -

The Pocket Oxford Theatre Company

THE POCKET OXFORD THEATRE COMPANY Presents Taming Shakespeare (Taming Of The Shrew) SECUNDARIA WORKPACK Teachers' note: This didactic material consists of pre-show activities designed to help teachers prepare the students for the experience of watching a piece of theatre in a foreign language. Due to The Pocket Oxford Theatre Company's interactive style and use of audience participation, certain details contained in this show will change over the course of the performance. The characters and plot will remain unaffected. SHAKESPEARE (1564-1616) William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, England in 1564. His parents were quite rich and he attended a grammar school where he studied Greek and Latin. He married Anne Hathaway in 1582. Shakespeare then moved to London to become a playwright and actor with the successful theatre company The Lord Chamberlain's Men. The company would later change its name to The King's Men in 1603. Shakespeare remained with the company until he retired in 1610. Shakespeare's earliest plays date from 1590 and by 1597 he was sufficiently rich to buy the second largest house in Stratford. The following year he became a partner in the new Globe Theatre, London. He wrote 37 plays in total and 154 sonnets (lyrical poems of 14 lines). His plays are catagorised into three genres; comedy, tragedy and history plays. The comedy, 'The Taming Of The Shrew', was one of Shakespeare's earliest plays (written in 1590) with his last play ('The Tempest') being written in 1611, after which he retired to Stratford, where he died in 1616, aged 52. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Some Thoughts Surrounding 2016Production of the Tempest

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by DSpace at Waseda University Some thoughts surrounding 2016 production of The Tempest UMEMIYA Yu The following note shows the result of an on going research on the play by William Shakespeare: The Tempest. The 2016 production at the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), one of the leading theatre companies in England, demonstrated another innovative version of the play on their main stage in Stratford-upon-Avon, followed by its tour down to Barbican theatre in London in 2017. It did not include an extraordinary interpretation or unique casting pattern but demonstrated the extended development of technology available on stage. This note introduces the feature and the reception of the production in the latter half, with a brief summary of the play and a survey of the performance history of The Tempest in the first half. The story of The Tempest Compared to other plays by Shakespeare, The Tempest is a rare example that follows the classical idea of three unities of time, place and action, deriving from 1 Aristotle, then prescribed by Philip Sydney in Renaissance England . The similar 2 structure has already practiced in The Comedy of Errors in 1594 , but while this early comedy is often described as a simple farce, The Tempest contains various complications in terms of plots and theatrical possibilities. The story of The Tempest opens with a storm at sea, conjured by the magic of Prospero, the main character of the play. He is manipulating the tempest from the 一二七nearby island where he lives with his daughter, Miranda, and shares the land with two other fantastic creatures, Ariel and Caliban. -

VII Shakespeare

VII Shakespeare GABRIEL EGAN, PETER J. SMITH, ELINOR PARSONS, CHLOE WEI-JOU LIN, DANIEL CADMAN, ARUN CHETA, GAVIN SCHWARTZ-LEEPER, JOHANN GREGORY, SHEILAGH ILONA O'BRIEN AND LOUISE GEDDES This chapter has four sections: 1. Editions and Textual Studies; 2. Shakespeare in the Theatre; 3. Shakespeare on Screen; 4. Criticism. Section 1 is by Gabriel Egan; section 2 is by Peter J. Smith; section 3 is by Elinor Parsons; section 4(a) is by Chloe Wei-Jou Lin; section 4(b) is by Daniel Cadman; section 4(c) is by Arun Cheta; section 4(d) is by Gavin Schwartz-Leeper; section 4(e) is by Johann Gregory; section 4(f) is by Sheilagh Ilona O'Brien; section 4(g) is by Louise Geddes. 1. Editions and Textual Studies One major critical edition of Shakespeare appeared this year: Peter Holland's Corio/anus for the Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Holland starts with 'A Note on the Text' (pp. xxiii-xxvii) that explains the process of modernization and how the collation notes work, and does so very well. Next Holland prints another note apologizing for but not explaining-beyond 'pressures of space'-his 44,000-word introduction to the play having 'no single substantial section devoted to the play itself and its major concerns, no chronologically ordered narrative of Corio/anus' performance history, no extensive surveying of the history and current state of critical analysis ... [and not] a single footnote' (p. xxxviii). After a preamble, the introduction itself (pp. 1-141) begins in medias res with Corio/anus in the 1930s, giving an account of William Poel's production in 1931 and one by Comedie-Frarn;:aise in 1933-4 and other reinterpretations by T.S. -

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 the OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019

The Oxfordian Volume 21 October 2019 ISSN 1521-3641 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The Oxfordian is the peer-reviewed journal of the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, a non-profit educational organization that conducts research and publication on the Early Modern period, William Shakespeare and the authorship of Shakespeare’s works. Founded in 1998, the journal offers research articles, essays and book reviews by academicians and independent scholars, and is published annually during the autumn. Writers interested in being published in The Oxfordian should review our publication guidelines at the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship website: https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/the-oxfordian/ Our postal mailing address is: The Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship PO Box 66083 Auburndale, MA 02466 USA Queries may be directed to the editor, Gary Goldstein, at [email protected] Back issues of The Oxfordian may be obtained by writing to: [email protected] 2 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 The OXFORDIAN Volume 21 2019 Acknowledgements Editorial Board Justin Borrow Ramon Jiménez Don Rubin James Boyd Vanessa Lops Richard Waugaman Charles Boynton Robert Meyers Bryan Wildenthal Lucinda S. Foulke Christopher Pannell Wally Hurst Tom Regnier Editor: Gary Goldstein Proofreading: James Boyd, Charles Boynton, Vanessa Lops, Alex McNeil and Tom Regnier. Graphics Design & Image Production: Lucinda S. Foulke Permission Acknowledgements Illustrations used in this issue are in the public domain, unless otherwise noted. The article by Gary Goldstein was first published by the online journal Critical Stages (critical-stages.org) as part of a special issue on the Shakespeare authorship question in Winter 2018 (CS 18), edited by Don Rubin. It is reprinted in The Oxfordian with the permission of Critical Stages Journal. -

Making Shakespeare Their ‘Buddy’

ISSN 2040‐2228 Vol. 4 No. 1 April 2013 Drama Research: international journal of drama in education Article 2 Making Shakespeare their ‘buddy’. Brian Lighthill National Drama Publications www.dramaresearch.co.uk [email protected] www.nationaldrama.org.uk Drama Research Vol. 4 No. 1 April 2013 Making Shakespare their ‘buddy’. (Should Shakespeare studies have a place in the curriculum – or is it just a load of Bardolatry?) ____________________________________________________________________ Brian Lighthill Abstract This article is based on a paper presented by Dr. Brian Lighthill at the RSC Worlds Together symposium, Tate Modern, London. October 7th, 2012 and is a brief summation of four years of observations and action research in one Warwickshire secondary school (2006‐10). The research project explored whether Shakespeare studies should have an ongoing place in the curriculum? In this article I map out the arguments for and against Shakespeare study then describe the modus operandi of the research process. A debate follows on how to make Shakespeare relevant for young learners – if the students are to own Shakespeare’s production can the issues in the fictional stories be made relevant to their real life world? I then summarize the research methodology and case study analysis and, at some length, discuss the discoveries made from many in‐depth interviews and questionnaires with seven randomly selected students, their parents and teachers over four years. Finally I explore the way forward for Shakespeare studies. This paper interrogates two questions: ‘Have Shakespeare’s plays any relevance to the lives of young people today – or is it just a load of Bardolatry?’ And, to miss‐quote Monty Pythons The Life of Brian, What have Shakespeare studies done for us? Article 2 Making Shakespeare their ‘buddy’ 2 Drama Research Vol. -

Study Guide the Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged) by Alison Howard © 2011 Table of Contents

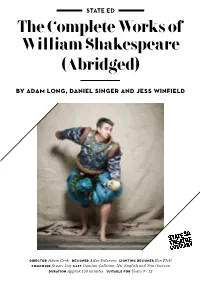

STATE ED The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged) by adam long, daniel singer and jess winfieldby adam long, daniel singer & jess winfield director Adam Cook designer Ailsa Paterson lighting designer Ben Flett composer Stuart Day cast Damian Callinan, Nic English and Tim Overton duration Approx 135 minutes suitable for Years 9 - 12 Performed by arrangement with Hal Leonard Australia Pty Ltd Images by Ailsa Paterson, Shane Reid and Utah Shakespearean Festival p.2 Study Guide The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged) By Alison Howard © 2011 Table of Contents Cast/Creative Team 4 Playwrights 5 Adam Long 5 Daniel Singer 5 Jess Winfield 6 About The Play 7 Excerpt from Shakespeare in Neon Colors 7 Pop Culture Allusion 8 From The Director 9 Actor Profiles 10 Damian Callinan 10 Nic English 11 Tim Overton 11 Synopsis 12 The Characters 13 The Language 13 About William Shakespeare 14 The Works of William Shakespeare 16 The Globe Theatre 16 Forms and Conventions 17 Conventions of Shakespearean Comedy 17 Improvisational Theatre 17 Interesting Reading 18 The Reduced Shakespeare Company 18 Set Design 19 Ailsa Paterson 19 Essay Questions 22 English Questions 22 Drama Questions 23 Design 23 Performance 23 Immediate Reactions 24 Design Roles 25 Further Resources 26 Shakespeare Study 26 Theatrical Comedy and Improvisation 26 Web Links* 26 References 26 p.3 Study Guide The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged) By Alison Howard © 2011 State Theatre Company of South Australia presents The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged) by adam long, daniel singer & jess winfield cast & creative team ensemble Damian Callinan Nic English Tim Overton director Adam Cook designer Alisa Paterson lighting designer Ben Flett composer Stuart Day p.4 Study Guide The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged) By Alison Howard © 2011 Playwrights adam long Founding Member/Writer/Performer Before “falling into” the business of Shakespearean performance, which he deemed only a hobby, Adam Long was an accountant, musician, and stand-up comic. -

The Shakespeare Apocrypha and Canonical Expansion in the Marketplace

The Shakespeare Apocrypha and Canonical Expansion in the Marketplace Peter Kirwan 1 n March 2010, Brean Hammond’s new edition of Lewis Theobald’s Double Falsehood was added to the ongoing third series of the Arden Shakespeare, prompting a barrage of criticism in the academic press I 1 and the popular media. Responses to the play, which may or may not con- tain the “ghost”2 of Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Cardenio, have dealt with two issues: the question of whether Double Falsehood is or is not a forgery;3 and if the latter, the question of how much of it is by Shakespeare. This second question as a criterion for canonical inclusion is my starting point for this paper, as scholars and critics have struggled to define clearly the boundar- ies of, and qualifications for, canonicity. James Naughtie, in a BBC radio interview with Hammond to mark the edition’s launch, suggested that a new attribution would only be of interest if he had “a big hand, not just was one of the people helping to throw something together for a Friday night.”4 Naughtie’s comment points us toward an important, unqualified aspect of the canonical problem—how big does a contribution by Shakespeare need to be to qualify as “Shakespeare”? The act of inclusion in an editedComplete Works popularly enacts the “canonization” of a work, fixing an attribution in print and commodifying it within a saleable context. To a very real extent, “Shakespeare” is defined as what can be sold as Shakespearean. Yet while canonization operates at its most fundamental as a selection/exclusion binary, collaboration compli- cates the issue. -

Shakespeare Trivia Anthology Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project (CASP) Shakespeare Learning Commons

1 Shakespeare Trivia Anthology Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project (CASP) Shakespeare Learning Commons FACT 1. Shakespeare is thought to have been born on April 23, 1564 and to have died the same day 52 years later. 2. During his lifetime, John Shakespeare (William’s father) did all of these jobs: glove maker, wool-dealer, moneylender, constable, chamberlain, alderman, bailiff, and justice of the peace. 3. Many of Shakespeare’s early sonnets are likely to have been written to another man: Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton. 4. In his will, Shakespeare left his wife Anne Hathaway his “second best bed with the furniture.” Second-best bed was not as bad as it sounds because the best bed was reserved for guests. 5. The open-air theatres that Shakespeare’s plays were first performed in were designed in the same style as the bear-baiting gardens (circular buildings with an open roof and a pit in the centre for the bear or the theatre audience). 6. A Google search for “Shakespeare” returns over 119 million hits. That’s more than Michael Jackson (42 million), Avril Lavigne (29 million) and Tiger Woods (21 million) combined. 7. Shakespeare invented over 1700 commonly used words in English (like “madcap,” “obscene,” “puking,” “outbreak,” “watchdog,” “addiction,” “cold-blooded,” “secure,” and “torture”). 8. Shakespeare’s plays have a vocabulary of some 17,000 words, four times what a well-educated English speaker would have. Shakespeare used 29,066 different words out of 884,647 words in all. 9. Shakespeare was so skilled with words that he used 7000 words only once––more than occur in the whole of the King James Bible. -

Not-Shakespeare and the Shakespearean Ghost Peter Kirwan a Book with the Title the Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Performanc

Not-Shakespeare and the Shakespearean Ghost Peter Kirwan A book with the title The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Performance sets up implicit exclusions from its cover page, in a word with complex and overlapping associations: ‘Shakespeare’. This is not a volume about the performances undertaken by an individual called Shakespeare, but performances of the writing performances of William Shakespeare, his dramatic (and perhaps poetic) works. Even at this most basic level, the term ‘Shakespeare’ is complex: a quarter to a third of the plays to which Shakespeare contributed contain the writing of other dramatists, and, as anyone who has been involved in creating theatre knows, the words of a playtext make up only one part of the whole play/performance of which the written texts are only one type of record. Shakespeare is shorthand for a body of work associated with Shakespeare, an industry spanning four centuries of reworking, rewriting, and reperforming this body, as the other essays in this book make clear. The instability of ‘Shakespeare and/in performance’ is already implicit in the seemingly infinite number of collaborative forms which the coupling of those terms makes possible, but this essay seeks to address a broader question: the performance of the wider early modern drama as Shakespearean performance. The overwhelming focus on Shakespeare over his contemporaries in criticism, production, and teaching around the world has led to a situation in which the ‘Shakespearean’ often stands for much more than Shakespeare. Even in surveying academic book titles, the selling power of Shakespeare’s name makes it synecdochic of a playing company (The Shakespeare Company), the theatre industry of his time (The Shakespearean Stage), his place of work (Shakespeare’s London), and the art of the early modern stage (The Shakespearean Drama).