Phd Thesis Emil Bjørn Hilton Saggau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference List

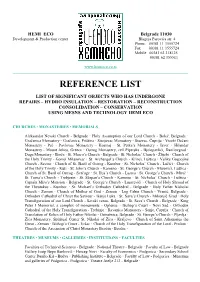

HEMI ECO Belgrade 11030 Development & Production center Blagoja Parovića str. 4 Phone 00381 11 3555724 Fax 00381 11 3555724 Mobile 00381 63 318125 00381 62 355511 www.hemieco.co.rs _______________________________________________________________________________________ REFERENCE LIST LIST OF SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS WHO HAS UNDERGONE REPAIRS – HYDRO INSULATION – RESTORATION – RECONSTRUCTION CONSOLIDATION – CONSERVATION USING MESNS AND TECHNOLOGY HEMI ECO CHURCHES • MONASTERIES • MEMORIALS Aleksandar Nevski Church - Belgrade · Holy Assumption of our Lord Church - Boleč, Belgrade · Gračanica Monastery - Gračanica, Priština · Sisojevac Monastery - Sisevac, Ćuprija · Visoki Dečani Monastery - Peć · Pavlovac Monastery - Kosmaj · St. Petka’s Monastery - Izvor · Hilandar Monastery - Mount Athos, Greece · Ostrog Monastery, cell Piperska - Bjelopavlići, Danilovgrad · Duga Monastery - Bioča · St. Marco’s Church - Belgrade · St. Nicholas’ Church - Žlijebi · Church of the Holy Trinity - Gornji Milanovac · St. Archangel’s Church - Klinci, Luštica · Velike Gospojine Church - Savine · Church of St. Basil of Ostrog - Kumbor · St. Nicholas’ Church - Lučići · Church of the Holy Trinity - Kuti · St. John’s Church - Kameno · St. George’s Church - Marovići, Luštica · Church of St. Basil of Ostrog - Svrčuge · St. Ilija’s Church - Lastva · St. George’s Church - Mirač · St. Toma’s Church - Trebjesin · St. Šćepan’s Church - Kameno · St. Nicholas’ Church - Luštica · Captain Miša’s Mansion - Belgrade · St. George’s Church - Lazarevići · Church of Holy Shroud of the Theotokos -

Type: Charming Village Culture Historic Monuments Scenic Drive

Type: Charming Village Culture Historic Monuments Scenic Drive See the best parts of Montenegro on this mini tour! We take you to visit three places with a great history - three places with a soul. This is tour where you will learn about the old customs in Montenegro, and also those who maintain till today. See the incredible landscapes and old buildings that will not leave you indifferent. Type: Charming Village, Culture, Historic Monuments, Scenic Drive Length: 6 Hours Walking: Medium Mobility: No wheelchairs Guide: Licensed Guide Language: English, Italian, French, German, Russian (other languages upon request) Every Montenegrin will say: "Who didn't saw Cetinje, haven't been in Montenegro!" So don't miss to visit the most significant city in the history and culture of Montenegro and it's numerous monuments: The Cetinje monastery, from which Montenegrin bishops ruled through the centuries; Palace of King Nikola, Montenegrin king who together with his daughters made connection with 4 European courts; Vladin Dom, art museum with huge collection of art paintings and historical symbols, numerous embassies and museums... After meeting your guide at the pier, you walk to your awaiting vehicle which will take you to Njegusi, a quiet mountain village. Njegusi Njegusi is a village located on the slopes of mount Lovcen. This village is best known as birthplace of Montenegro's royal dynasty of Petrovic, which ruled Montenegro from 1696 to 1918. Njegusi is a birthplace of famous Montenegrin bishop and writer – Petar II Petrovic Njegos. The village is also significant for its well- preserved traditional folk architecture. Cheese and smoked ham (prosciutto) from Njegusi are made solely in area around Njegusi, are genuine contributions to Montenegrin cuisine. -

American Reportage and Propaganda in the Wars of Yugoslav Secession

WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of International Affairs in University College The Rhetorical Assault: American Reportage and Propaganda in the Wars of Yugoslav Secession by Sarah Wion A thesis presented to University College of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts St. Louis, Missouri TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction: Media Spin at the Sochi Olympics 1 II. Propaganda: A Theoretical Approach 6 Propaganda in a Contemporary Conceptual Construct 8 Case Studies of Propaganda in the Media 13 III. Propaganda: A Diachronic Analysis 16 IV. Yugoslavia a State in the Crosshairs of Public Opinion 23 Yugoslavia: A Cold War Companion 24 Serbia: A Metaphor for Russian Dismantlement 27 V. Recycled Frames and Mental Shorthand 31 Milosevic: A Modern-Day Hitler 33 TIME Magazine and Bosnian Death Camps 41 VI. Sanctions and Safe Areas: Antagonistic Aid 47 VII. Case Studies of Victimization in Krajina and Kosovo VIII. Conclusion: Balkan Coverage – A New Paradigm ii DEDICATION To the peoples of the former Yugoslavia – may every inquiry bring a greater sense of justice and peace to the region. v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Rhetorical Assault: American Reportage and Propaganda in the Wars of Yugoslav Secession by Sarah Wion Master of Arts in International Affairs Washington University in St. Louis Professor Marvin Marcus, Chair The contemporary political paradigm for democratic states is precariously balanced on the metaphoric scale of public opinion. As such, policy consensus is, in theory, influenced and guided by the public; however, publications like The Crisis of Democracy poignantly illustrate the reluctance of political elites to relinquish control over the state agenda, especially with respect to foreign affairs. -

RELIGION and YOUTH in CROATIA Dinka Marinović Jerolimov And

RELIGION AND YOUTH IN CROATIA Dinka Marinović Jerolimov and Boris Jokić Social and Religious Context of Youth Religiosity in Croatia During transitional periods, the post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe shared several common characteristics regarding religious change. These can be roughly summarized as the influence of religion during the collapse of the communist societal system; the revitalization of religion and religiosity; a national/religious revival; an increase in the number of new religious movements; the politiciza- tion of religion and “religionization” of politics; and the as pirations of churches to regain positions they held in the pre-Communist period (Borowik, 1997, 1999; Hornsby-Smith, 1997; Robertson, 1989; Michel, 1999; Vrcan, 1999). In new social and political circumstances, the posi- tion of religion, churches, and religious people significantly changed as these institutions became increasingly present in public life and the media, as well as in the educational system. After a long period of being suppressed to the private sphere, they finally became publicly “visible”. The attitude of political structures, and society as a whole, towards religion and Churches was clearly reflected in institutional and legal arrangements and was thus reflected in the changed social position of religious communities. These phenomena, processes and tendencies can be recognized as elements of religious change in Croatia as well. This particularly refers to the dominant Catholic Church, whose public role and impor- tance -

The Role of Churches and Religious Communities in Sustainable Peace Building in Southeastern Europe”

ROUND TABLE: “THE ROLE OF CHUrcHES AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES IN SUSTAINABLE PEACE BUILDING IN SOUTHEASTERN EUROPE” Under THE auSPICES OF: Mr. Terry Davis Secretary General of the Council of Europe Prof. Jean François Collange President of the Protestant Church of the Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine (ECAAL) President of the Council of the Union of Protestant Churches of Alsace and Lorraine President of the Conference of the Rhine Churches President of the Conference of the Protestant Federation in France Strasbourg, June 19th - 20th 2008 1 THE ROLE OF CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES IN SUSTAINABLE PEACE BUILDING PUBLISHER Association of Nongovernmental Organizations in SEE - CIVIS Kralja Milana 31/II, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia Tel: +381 11 3640 174 Fax: +381 11 3640 202 www.civis-see.org FOR PUBLISHER Maja BOBIć CHIEF EDITOR Mirjana PRLJević EDITOR Bojana Popović PROOFREADER Kate DEBUSSCHERE TRANSLATORS Marko NikoLIć Jelena Savić TECHNICAL EDITOR Marko Zakovski PREPRESS AND DESIGN Agency ZAKOVSKI DESIGN PRINTED BY FUTURA Mažuranićeva 46 21 131 Petrovaradin, Serbia PRINT RUN 1000 pcs YEAR August 2008. THE PUBLISHING OF THIS BOOK WAS supported BY Peace AND CRISES Management FOUndation LIST OF CONTEST INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 APPELLE DE STraSBOURG ..................................................................................................... 7 WELCOMING addrESSES ..................................................................................................... -

Mozaicul Voivodinean – Fragmente Din Cultura Comunităților Naționale Din Voivodina – Ediția Întâi © Autori: Aleksandr

Mozaicul voivodinean – fragmente din cultura comunităților naționale din Voivodina – Ediția întâi © Autori: Aleksandra Popović Zoltan Arđelan © Editor: Secretariatul Provincial pentru Educație, Reglementări, Adminstrație și Minorități Naționale -Comunități Naționale © Сoeditor: Institutul de Editură „Forum”, Novi Sad Referent: prof. univ. dr. Žolt Lazar Redactorul ediției: Bojan Gregurić Redactarea grafică și pregătirea pentru tipar: Administrația pentru Afaceri Comune a Organelor Provinciale Coperta și designul: Administrația pentru Afaceri Comune a Organelor Provinciale Traducere în limba română: Mircea Măran Lectorul ediției în limba română: Florina Vinca Ilustrații: Pal Lephaft Fotografiile au fost oferite de arhivele: - Institutului Provincial pentru Protejarea Monumentelor Culturale - Muzeului Voivodinei - Muzeului Municipiului Novi Sad - Muzeului municipiului Subotica - Ivan Kukutov - Nedeljko Marković REPUBLICA SERBIA – PROVINCIA AUTONOMĂ VOIVODINA Secretariatul Provincial pentru Educație, Reglementări, Adminstrație și Minorități Naționale -Comunități Naționale Proiectul AFIRMAREA MULTICULTURALISMULUI ȘI A TOLERANȚEI ÎN VOIVODINA SUBPROIECT „CÂT DE BINE NE CUNOAŞTEM” Tiraj: 150 exemplare Novi Sad 2019 1 PREFAȚĂ AUTORILOR A povesti povestea despre Voivodina nu este ușor. A menționa și a cuprinde tot ceea ce face ca acest spațiu să fie unic, recognoscibil și specific, aproape că este imposibil. În timp ce faceți cunoștință cu specificurile acesteia care i-au inspirat secole în șir pe locuitorii ei și cu operele oamenilor de seamă care provin de aci, vi se deschid și ramifică noi drumuri de investigație, gândire și înțelegere a câmpiei voivodinene. Tocmai din această cauză, nici autorii prezentei cărți n-au fost pretențioși în intenția de a prezenta tot ceea ce Voivodina a fost și este. Mai întâi, aceasta nu este o carte despre istoria Voivodinei, și deci, nu oferă o prezentare detaliată a istoriei furtunoase a acestei părți a Câmpiei Panonice. -

Emancipation in St. Croix; Its Antecedents and Immediate Aftermath

N. Hall The victor vanquished: emancipation in St. Croix; its antecedents and immediate aftermath In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 58 (1984), no: 1/2, Leiden, 3-36 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl N. A. T. HALL THE VICTOR VANQUISHED EMANCIPATION IN ST. CROIXJ ITS ANTECEDENTS AND IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH INTRODUCTION The slave uprising of 2-3 July 1848 in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, belongs to that splendidly isolated category of Caribbean slave revolts which succeeded if, that is, one defines success in the narrow sense of the legal termination of servitude. The sequence of events can be briefly rehearsed. On the night of Sunday 2 July, signal fires were lit on the estates of western St. Croix, estate bells began to ring and conch shells blown, and by Monday morning, 3 July, some 8000 slaves had converged in front of Frederiksted fort demanding their freedom. In the early hours of Monday morning, the governor general Peter von Scholten, who had only hours before returned from a visit to neighbouring St. Thomas, sum- moned a meeting of his senior advisers in Christiansted (Bass End), the island's capital. Among them was Lt. Capt. Irminger, commander of the Danish West Indian naval station, who urged the use of force, including bombardment from the sea to disperse the insurgents, and the deployment of a detachment of soldiers and marines from his frigate (f)rnen. Von Scholten kept his own counsels. No troops were despatched along the arterial Centreline road and, although he gave Irminger permission to sail around the coast to beleaguered Frederiksted (West End), he went overland himself and arrived in town sometime around 4 p.m. -

Representations of Lancet Or Phlebotome in Serbian Medieval

Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2015 Sep-Oct;143(9-10):639-643 DOI: 10.2298/SARH1510639P ИСТОРИЈА МЕДИЦИНЕ / HISTORY OF MEDICINE UDC: 75.052.046.3(497.11)"04/14" 639 Representations of Lancet or Phlebotome in Serbian Medieval Art Sanja Pajić1, Vladimir Jurišić2 1University of Kragujevac, Faculty of Philology and Arts, Department of Applied and Fine Arts, Kragujevac, Serbia; 2University of Kragujevac, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Kragujevac, Serbia SUMMARY The topic of this study are representations of lancet or phlebotome in frescoes and icons of Serbian medieval art. The very presence of this medical instrument in Serbian medieval art indicates its usage in Serbian medical practices of the time. Phlebotomy is one of the oldest forms of therapy, widely spread in medieval times. It is also mentioned in Serbian medical texts, such as Chilandar Medical Codex No. 517 and Hodoch code, i.e. translations from Latin texts originating from Salerno–Montpellier school. Lancet or phlebotome is identified based on archaeological finds from the Roman period, while finds from the Middle Ages and especially from Byzantium have been scarce. Analyses of preserved frescoes and icons has shown that, in comparison to other medical instruments, lancet is indeed predominant in Serbian medieval art, and that it makes for over 80% of all the representations, while other instruments have been depicted to a far lesser degree. Examination of written records and art points to the conclusion that Serbian medieval medicine, both in theory and in practice, belonged entirely to European -

The Religious Freedom in Croatia: the Current State and Perspectives

Centrum Analiz Strategicznych Instytutu Wymiaru Sprawiedliwości For the freedom to profess religion in the contemporary world. Counteracting the causes of discrimination and helping the persecuted based on the example of Christians Saša Horvat The religious freedom in Croatia: the current state and perspectives [Work for the Institute of Justice] Warsaw 2019 The Project is co-financed by the Justice Fund whose administrator is the Minister of Justice Content Introduction / 3 1. Definitions of religious persecution and freedom to profess religion / 4 1.1. The rologueP for freedom to profess religion / 4 1.1.1. Philosophical and theological perspectives of the concept of freedom / 4 1.1.2. The concept of religion / 5 1.1.3. The freedom to profess religion / 7 1.2. The freedom to profess religion – legislative framework / 7 1.2.1. European laws protecting the freedom to profess religion / 7 1.2.2. Croatian laws protecting the freedom to profess religion / 8 1.3. Definitions of religious persecution and intolerance toward the freedom to profess religion / 9 1.3.1. The religious persecution / 9 1.3.1.1. Terminological clarifications / 10 2. The freedom to profess religion and religious persecution / 10 2.1. The situation in Europe / 10 2.2. The eligiousr persecution in Croatia / 13 3. The examples of religious persecutions in Croatia or denial of religious freedom / 16 3.1. Religion persecution by the clearing of the public space / 16 3.2. Religion symbols in public and state institutions / 19 3.3. Freedom to profess religious teachings and attitudes / 22 3.3.1. Freedom to profess religious teachings and attitudes in schools / 22 3.3.2. -

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution

Cultural Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution Introduction In his poem, The Second Coming (1919), William Butler Yeats captured the moment we are now experiencing: Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. As we see the deterioration of the institutions created and fostered after the Second World War to create a climate in which peace and prosperity could flourish in Europe and beyond, it is important to understand the role played by diplomacy in securing the stability and strengthening the shared values of freedom and democracy that have marked this era for the nations of the world. It is most instructive to read the Inaugural Address of President John F. Kennedy, in which he encouraged Americans not only to do good things for their own country, but to do good things in the world. The creation of the Peace Corps is an example of the kind of spirit that put young American volunteers into some of the poorest nations in an effort to improve the standard of living for people around the globe. We knew we were leaders; we knew that we had many political and economic and social advantages. There was an impetus to share this wealth. Generosity, not greed, was the motivation of that generation. Of course, this did not begin with Kennedy. It was preceded by the Marshall Plan, one of the only times in history that the conqueror decided to rebuild the country of the vanquished foe. -

Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich. Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich

Photo courtesy Alaska State Library, Michael Z. Vinokouroff Collection P243-1-082. Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich. Sebastian Archimandrite Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich. Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich SERBIAN ORTHODOX APOSTLE TO AMERICA by Hieromonk Damascene . A A U S during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, Archimandrite B Sebastian Dabovich has the distinction of being the first person born in the United States of America to be ordained as an Orthodox priest, 1 and also the first native-born American to be tonsured as an Orthodox monk. His greatest distinction, however, lies in the tremen- dous apostolic, pastoral, and literary work that he accomplished dur- ing the forty-eight years of his priestly ministry. Known as the “Father of Serbian Orthodoxy in America,” 2 he was responsible for the found- ing of the first Serbian churches in the New World. This, however, was only one part of his life’s work, for he tirelessly and zealously sought to spread the Orthodox Faith to all peoples, wherever he was called. He was an Orthodox apostle of universal significance. Describing the vast scope of Fr. Sebastian’s missionary activity, Bishop Irinej (Dobrijevic) of Australia and New Zealand has written: 1 Alaskan-born priests were ordained before Fr. Sebastian, but this was when Alaska was still part of Russia. 2 Mirko Dobrijevic (later Irinej, Bishop of Australia and New Zealand), “The First American Serbian Apostle—Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich,” Again, vol. 16, no. 4 (December 1993), pp. 13–14. THE ORTHODOX WORD “Without any outside funding or organizational support, he carried the gospel of peace from country to country…. -

Srbska Pravoslavna Cerkev Na Slovenskem Med Svetovnima Vojnama

31 ZBIRKA RAZPOZNAVANJA RECOGNITIONES Bojan Cvelfar SRBSKA PRAVOSLAVNA CERKEV NA SLOVENSKEM MED SVETOVNIMA VOJNAMA INŠTITUT ZA NOVEJŠO ZGODOVINO Ljubljana 2017 31 ZBIRKA RAZPOZNAVANJA RECOGNITIONES Bojan Cvelfar SRBSKA PRAVOSLAVNA CERKEV NA SLOVENSKEM MED SVETOVNIMA VOJNAMA 3 ZALOŽBA INZ Odgovorni urednik dr. Aleš Gabrič Založnik Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino ZBIRKA RAZPOZNAVANJA / RECOGNITIONES 31 ISSN 2350-5664 Bojan Cvelfar SRBSKA PRAVOSLAVNA CERKEV NA SLOVENSKEM MED SVETOVNIMA VOJNAMA Sozaložnik Arhiv Republike Slovenije št. 31 zbirke Razpoznavanja/ Recognitiones Recenzenta dr. Jurij Perovšek dr. Božo Repe Jezikovni pregled Polona Kekec Prevod povzetka Borut Praper Oblikovanje Barbara Bogataj Kokalj Tisk Medium d.o.o. Naklada 400 izvodov Izid knjige sta Javna agencija za raziskovalno dejavnost Republike podprla Slovenije Srbska pravoslavna cerkev – cerkvena občina Ljubljana, Kulturno – prosvetni center »Sveti Ciril in Metod« CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 930.85(497.4)"1918/1941":271.222(497.11) 271.222(497.11)(091) 271.2(497.4)"1918/1941" CVELFAR, Bojan Srbska pravoslavna cerkev na Slovenskem med svetovnima vojnama / Bojan Cvelfar ; [prevod povzetka Borut Praper]. - Ljubljana : Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2017. - (Zbirka Razpoznavanja = Recognitiones ; 31) ISBN 978-961-6386-81-4 292114176 4 PREDGOVOR VSEBINA 9 PREDGOVOR 13 VZHODNA CERKEV DO OBRAVNAVANEGA OBDOBJA 14 Pravoslavna cerkev in njena organizacija 20 Srbska pravoslavna cerkev 25 Razdrobljena srbska cerkev pred zedinjenjem