The Contributions of Paul Goodman to the Clinical, Social, and Political Implications of Boundary Disturbances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man. -

PAUL GOODMAN (1911-1972) Edgar Z

The following text was originally published in Prospects : the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO : International Bureau of Education), vol . XXIII, no . 3/4, June 1994, p. 575-95. ©UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 1999 This document may be reproduced free of charge as long as acknowledgement is made of the source. PAUL GOODMAN (1911-1972) Edgar Z. Friedenberg1 Paul Goodman died of a heart attack on 2 August 1972, a month short of his 61st birthday. This was not wholly unwise. He would have loathed what his country made of the 1970s and 1980s, even more than he would have enjoyed denouncing its crassness and hypocrisy. The attrition of his influence and reputation during the ensuing years would have been difficult for a figure who had longed for the recognition that had eluded him for many years, despite an extensive and varied list of publications, until Growing up absurd was published in 1960, which finally yielded him a decade of deserved renown. It is unlikely that anything he might have published during the Reagan-Bush era could have saved him from obscurity, and from the distressing conviction that this obscurity would be permanent. Those years would not have been kind to Goodman, although he was not too kind himself. He might have been and often was forgiven for this; as well as for arrogance, rudeness and a persistent, assertive homosexuality—a matter which he discusses with some pride in his 1966 memoir, Five years, which occasionally got him fired from teaching jobs. However, there was one aspect of his writing that the past two decades could not have tolerated. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

Paul Goodman and the Biography of Sexual Modernity David S

Document generated on 10/02/2021 9:40 p.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada Paul Goodman and the Biography of Sexual Modernity David S. Churchill The Biographical (Re)Turn Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2010 This article is a preliminary exploration of the relationship between the auto-biographical writings of radical US intellectual Paul Goodman and his URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1003087ar theorizing of sexuality’s links to the project of political liberation. Goodman’s DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1003087ar life writing was integrated into his social and political critique of mid-twentieth century society, as well as his more scholarly pursuits of See table of contents psychology and sociology. In this way, Goodman’s work needs to be seen as generative of the dialectic of sexually modernity, which integrated intimate queer sexual experiences with conceptual, intellectual, and elite discourses on sexuality. Publisher(s) The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada ISSN 0847-4478 (print) 1712-6274 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Churchill, D. S. (2010). Paul Goodman and the Biography of Sexual Modernity. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, 21(2), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.7202/1003087ar All Rights Reserved © The Canadian Historical Association / La Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit historique du Canada, 2010 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

THE WORLD of PAUL GOODMAN Anarchy 11

THE WORLD OF PAUL GOODMAN Reviews of COMMUNITAS, UTOPIAN ESSAYS and GROWING UP ABSURD Paul Goodman THE CHILDREN AND PSYCHOLOGY Harold Drasdo THE CHARACTER BUILDERS A% S. Neill SUMMERHILL vs. STANDARD EDUCATION Ana$&'( 1) A JOURNAL OF ANARCHIST IDEAS 1s 6d or 25 cents inside front cover Con.ents of No%)) *an!a$( )/+, The World of Paul Goodman John Ellerby 1 Communitas Revisited 3 Youth and Absurdity 14 Practical Proposals 17 The Children and Psychology Paul Goodman 20 The Character Builders Harold Drasdo 25 Summerhill Education vs. Standard Education A. S. Neill 29 Cover: Bibliography for the New Commune (from Communitas) O.'e$ iss!es of ANARCHY: No.1. Alex Comfort on Sex-and-Violence, Nicolas Walter on the New Wave, and articles on education, opportunity, and Galbraith. No.2. A symposium on Workers' Control. No.3. What does anarchism mean today?, and articles on Africa, the 'Long Revolution' and exceptional children. No.4. George Molnar on conflicting strains in anarchism, Colin Ward on the breakdown of institutions. No.5. A symposium on the Spanish Revolution of 1936. No.6. Anarchy and Cinema: articles on Vigo, Buñuel and Flaherty. Two experimental film-makers discuss their work. No.7. A symposium on Adventure Playgrounds. No.8. Anarchists and Fabians, Kenneth Maddock on action anthropology, Reg Wright on erosion inside capitalism, Nicolas Walter on Orwell. No.9. A symposium on Prison. No.10. Alan Sillitoe's Key to the Door, Colin MacInnes on crime, Augustus John on utopia, Committee of 100 seminar on industry and workers' control. Subscribe to ANARCHY single copies 1s. -

PAUL GOODMAN CHANGED MY LIFE a Film by Jonathan Lee

PAUL GOODMAN CHANGED MY LIFE a film by Jonathan Lee Booking Contact: Clemence Taillandier, Zeitgeist Films 201-736-0261 • [email protected] Marketing Contacts: Nancy Gerstman & Emily Russo, Zeitgeist Films 212-274-1989 • [email protected] • [email protected] A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE PAUL GOODMAN CHANGED MY LIFE A Film by Jonathan Lee Paul Goodman was once so ubiquitous in the American zeitgeist that he merited a “cameo” in Woody Allenʼs Annie Hall. Author of legendary bestseller Growing Up Absurd (1960), Goodman was also a poet, 1940s out queer (and family man), pacifist, visionary, co-founder of Gestalt therapy—and a moral compass for many in the burgeoning counterculture of the ʼ60s. Paul Goodman Changed My Life immerses you in an era of high intellect (that heady, cocktail-glass juncture that Mad Men has so effectively exploited) when New York was peaking culturally and artistically; when ideas, and the people who propounded them, seemed to punch in at a higher weight class than they do now. Using a treasure trove of archival multimedia—selections from Goodmanʼs poetry (read by Garrison Keillor and Edmund White); quotes from Susan Sontag, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Noam Chomsky; plentiful footage of Goodman himself; plus interviews with his family, peers and activists—director/producer Jonathan Lee and producer/editor Kimberly Reed (Prodigal Sons) have woven together a rich portrait of an intellectual heavyweight whose ideas are long overdue for rediscovery. PAUL GOODMAN BIO Born in New York City in 1911, Paul Goodman labored in obscurity as a writer and freelance intellectual until 1960 when the publication of Growing Up Absurd made him famous and a significant moral force of the decade. -

Paul Goodman: Advocate of Community-Based Education

Paul Goodman: Advocate of Community-Based Education by Steve Welzer Green Horizon Magazine, Spring 2007 [Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes below are taken from Paul Goodman's contribution to the discussion volume Summerhill: For and Against (Hart Publishing Company, New York, 1970), pages 205-222] Few American writers were more prolific than Paul Goodman during the middle decades of the twentieth century, and few matched Goodman's scope of inquiry. His short stories, novels, poems, plays, and essays covered a wide range of subjects—politics, social theory, education, urban design, literary criticism, even psychotherapy. Theodore Roszak, in The Making of a Counter Culture (1969), named Goodman as one of the primary influences on the young activists of that period. Goodman consistently paid close attention to the preoccupations, passions, and aspirations of the youthful dissidents, even if he didn't always approve of their agenda or modes of expression. Goodman lectured at college campuses all around the country during the sixties and wrote articles that appeared widely in the youth-centric underground press. After 1968, as the student left was careening toward a reckless and hotheaded Marxism- Leninism-Maoism, Goodman was urging consideration of an alternative: a pacific, ecologically-aware, decentralized—some might now say "proto-Green"—form of anarchism. He disapproved of the imprudence and fanaticism of many of the young radicals, but he was not surprised by it. He had earlier termed their conditions of adolescence "absurd" (Growing Up Absurd, 1960). Where is the basis for maturity, morality, and integrity, he asked, when so much of adult life typically revolves around the production of widgets for faceless masses in order to maximize profits? Alternative modes of education and socialization Goodman is well-remembered as a critic of the industrial state and its dispiriting system of "compulsory mis-education," but he is not often cited for his positive vision of alternative modes of education and socialization of the young. -

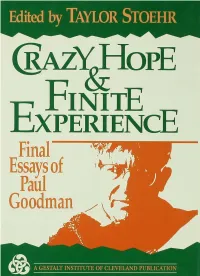

CRAZY HOPE and FINITE EXPERIENCE Crazy Hope and Finite Experience

..• A Gestalt Institute of Cleveland publication CRAZY HOPE AND FINITE EXPERIENCE Crazy Hope and Finite Experience Final Essays of Paul Goodman Taylor Stoehr, editor Jossey,Bass Inc. • San Francisco Copyright© 1994 by jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers, 350 Sansome Street, San Francisco, California 94104. Copyright under International, Pan American, and Universal Copyright Conventions. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form-except for brief quotation (not to exceed 1,000 words) in a review or professional work-without permission in writing from the publishers. e A Gestalt Institute of Cleveland publication Substantial discounts on bulk quantities ofjossey-Bass books are available to corporations, professional associations, and other organizations. For details and discount information, contact the special sales department at jossey·Bass Inc., Publishers. (415) 433-1740; Fax (415) 433-0499. For international orders, please contact your local Paramount Publishing International office. Manufactured in the United States of America. Nearly all jossey-Bass books and jackets are printed on recycled paper that contains at least 50 percent recycled waste, including 10 percent postconsumer waste. Many of our materials are also printed with either soy· or vegetable· based ink; during the printing process these inks emit fewer volatile organic compounds (VOCs) than petroleum-based inks. VOCs contrib· ute to the formation of smog. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Goodman, Paul, 1911-1972. Crazy hope and finite experience : final essays of Paul Goodman / [edited by) Taylor Stoehr.- 1st ed. p. em.- (Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series) ISBN Q. 7879-0016-8 I. Stoehr, Taylor, date. -

Graffiti and the Imagination: Paul Goodman in His Short Stories

Graffiti and the imagination: Paul Goodman in his short stories The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Stoehr, Taylor. 1995. Graffiti and the imagination: Paul Goodman in his short stories. Harvard Library Bulletin 5 (3), Fall 1994: 20-37. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42664025 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 20 Graffiti and the Imagination: Paul Goodman in His Short Stories TaylorStoehr he Houghton Library acquired the papers of the author and social philoso- T pher Paul Goodman from his widow, Sally Goodman, in 1989. These papers have now been cataloged, and are available to scholars. Goodman did not rou- tinely save his correspondence, but the collection does contain letters to him, be- ginning in the thirties, when he was a young man, from friends and family; and it also includes copies of his numerous open letters to newspapers and to public of- ficials during the decade of his fame as a social critic. Much more extensive mate- rials of a literary nature have been preserved, from every period and genre of his long and extremely varied career, though his working notes for only one of his thirty-odd books, Speakingand LAnguage,have survived. Typescripts exist for most TAYLOR STOEHR, professor of of his shorter published works, both fiction and essays, as well as for a good many English at the University of unpublished pieces. -

THE PAUL Goodman READER

THE paul GOODmAn READER Paul Goodman • Edited by Taylor Stoehr A one-man think-tank for the New Left, Paul Goodman wrote over 30 books, most of them before his decade of fame as a social critic in the Sixties. A Reader that does him justice must be a compendious volume, with excerpts not only from bestsellers like Growing Up Absurd, but also from his landmark books on education, community planning, anarchism, psychotherapy, language theory, and poetics. Samples as well from The Empire City, a comic novel reviewers compared to Don Quixote, prizewinning short stories, and scores of poems that led Americaʼs most respected poetry reviewer, Hayden Carruth, to exclaim, “Not one dull page. Itʼs almost unbelievable.” Goodman called himself as an old-fashioned man of letters, which meant that all these various disciplines and occasions added up to a single abiding concern for the human plight in perilous times, and for human promise and achieved grandeur, love and hope. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Paul Goodman, known in his day as “the philosopher of the New Left,” set the agenda for the youth movement of the Sixties with his bestselling Growing Up Absurd. He produced new books every year throughout that turbulent decade, while lecturing to hundreds of audiences on the nationʼs campuses, covering subjects that ranged from movement politics to education and SUBJECT CATEGORY community planning, from psychotherapy and religion to literature, language POLITICS/ theory and media. There was little that did not fall within his purview as an literature old-fashioned “man of letters.” During this same heady period of his fame he also published his public letters and his journals, the Living Theatre performed PRICE his plays, his poems were set to music, and his fiction was chosen for book $28.95 club distribution. -

Paul Goodman, 1970, New Reformation

NEW REFORMATION NOTES of a NEOLITHIC CONSERVATIVE oc?id=10400622&ppg=1 formation : Notes of a Neolithic Conservative (2nd Edition). "His pleading, sane, frank, troubled and by now tired voice /dominicanuc/D is one of the truest and wisest in American life." -KENNETH KENISTON, NEW YORK TIMES Goodman, Paul (Author). New Re Oakland, CA, USA: PM Press, 2010. p i. 2010. Press, PM USA: CA, Oakland, http://site.ebrary.com/lib New Reformation Notes of a Neolithic Conservative Paul Goodman oc?id=10400622&ppg=2 formation : Notes of a Neolithic Conservative (2nd Edition). /dominicanuc/D Goodman, Paul (Author). New Re Oakland, CA, USA: PM Press, 2010. p 1. 2010. Press, PM USA: CA, Oakland, http://site.ebrary.com/lib The New Reformation: Notes of a Neolithic Conservative The New Reformation� 2010 by Sally Goodman Introduction 102010 by Michael C. Fisher This edition © 2010 by PM Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmittedby any means without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-60486-056-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009901372 Cover: John Yates Interior design by briandesign PM Press oc?id=10400622&ppg=3 PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 formation : Notes of a Neolithic Conservative (2nd Edition). www.pmpress.org Printed in the USA on recycled paper. /dominicanuc/D Goodman, Paul (Author). New Re Oakland, CA, USA: PM Press, 2010. p 2. 2010. Press, PM USA: CA, Oakland, http://site.ebrary.com/lib Contents Introduction by Michael C. Fisher 5 Preface 31 PART ONE Sciences and Professions Chapter 1 37 Chapter 2 53 Chapter 3 61 Chapter 4 70 PART TWO Education of the Young Chapter 5 85 Chapter 6 104 Chapter 7 112 Chapter 8 118 PART THREE Legitimacy Chapter 9 129 Chapter 10 143 Chapter 11 160 Chapter 12 170 oc?id=10400622&ppg=4 PART FOUR Notes of a Neolithic Conservative formation : Notes of a Neolithic Conservative (2nd Edition). -

Paul Goodman – Notes of a Neolithic Conservative

Font Size: A A A Notes of a Neolithic Conservative Paul Goodman MARCH 26, 1970 ISSUE 1. For green grass and clean rivers, children with bright eyes and good color, and people safe from being pushed around—for a few things like these, I find I am pretty ready to think away most other political, economic, and technological advantages. Some Conservatives seem to want to go back to the Administration of McKinley. But when people are subject to universal social engineering and the biosphere itself is in danger, we need a more neolithic conservatism. So I propose maxims like “the right purpose of elementary schooling is to delay socialization” and “innovate in order to simplify, otherwise as sparingly as possible.” Liberals want to progress, that is, to up the rate of growth by political means. But if the background conditions are tolerable, society will probably progress anyway, for people have energy, curiosity, and ingenuity. All the resources of the State cannot anyway educate a child, improve a neighborhood, give dignity to an oppressed man. Sometimes the state can provide capital for people to do for themselves; but mostly it should stop standing in the way and doing damage and wasting wealth. Political power may come out of the barrel of a gun, but, as John L. Lewis said, “You can’t dig coal with bayonets.” 2. Edmund Burke had a good idea of conservatism, that existing community bonds are destroyed at peril; they are not readily replaced, society becomes superficial and government illegitimate. It takes the rising of a prophet or some other irrational cataclysm to create new community bonds.