Information Transmission in Communication Games Signaling with an Audience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confirmation Bias in Criminal Cases

Moa Lidén Confirmation Bias in Criminal Cases Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Sal IV, Universitetshuset, Biskopsgatan 3, 753 10 Uppsala, Uppsala, Friday, 28 September 2018 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Laws. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Steven Penrod (John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University New York). Abstract Lidén, M. 2018. Confirmation Bias in Criminal Cases. 284 pp. Uppsala: Department of Law, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2720-6. Confirmation bias is a tendency to selectively search for and emphasize information that is consistent with a preferred hypothesis, whereas opposing information is ignored or downgraded. This thesis examines the role of confirmation bias in criminal cases, primarily focusing on the Swedish legal setting. It also examines possible debiasing techniques. Experimental studies with Swedish police officers, prosecutors and judges (Study I-III) and an archive study of appeals and petitions for new trials (Study IV) were conducted. The results suggest that confirmation bias is at play to varying degrees at different stages of the criminal procedure. Also, the explanations and possible ways to prevent the bias seem to vary for these different stages. In Study I police officers’ more guilt presumptive questions to apprehended than non-apprehended suspects indicate a confirmation bias. This seems primarily driven by cognitive factors and reducing cognitive load is therefore a possible debiasing technique. In Study II prosecutors did not display confirmation bias before but only after the decision to press charges, as they then were less likely to consider additional investigation necessary and suggested more guilt confirming investigation. -

Chapter 12 Game Theory and Ppp*

CHAPTER 12 GAME THEORY AND PPP* By S. Ping Ho Associate Professor, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, National Taiwan University. Email: [email protected] †Shimizu Visiting Associate Professor, Dept. of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Stanford University. 1. INTRODUCTION Game theory can be defined as “the study of mathematical models of conflict and cooperation between intelligent rational decision-makers” (Myerson, 1991). It can also be called “conflict analysis” or “interactive decision theory,” which can more accurately express the essence of the theory. Still, game theory is the most popular and accepted name. In PPPs, conflicts and strategic interactions between promoters and governments are very common and play a crucial role in the performance of PPP projects. Many difficult issues such as opportunisms, negotiations, competitive biddings, and partnerships have been challenging the wisdom of the PPP participants. Therefore, game theory is very appealing as an analytical framework to study the interaction and dynamics between the PPP participants and to suggest proper strategies for both governments and promoters. Game theory modelling method will be used throughout this chapter to analyze and build theories on some of the above challenging issues in PPPs. Through the game theory modelling, a specific problem of concern is abstracted to a level that can be analyzed without losing the critical components of the problem. Moreover, new insights or theories for the concerned problem are developed when the game models are solved. Whereas game theory modelling method has been broadly applied to study problems in economics and other disciplines, only until recently, this method has been * First Draft, To appear in The Routledge Companion to Public-Private Partnerships, Edited by Professor Piet de Vries and Mr. -

Syllabus Game Thoery

SYLLABUS GAME THEORY, PHD The lecture will take place from 11:00 am to 2:30 pm every course day. Here is a list with the lecture dates and rooms : 6.6. 11:00-14:30 SR 9 7.6. 11:00-14:30 SR 4 8.6. 11:00-14:30 SR 4 9.6. 11:00-14:30 SR 4 10.6. 11:00-14:30 SR 4 Midterm: Mo, 20.6. 10:00-12:00 Room TBA 20.6. 12:30-14:30 SR 9 21.6. 11:00-14:30 SR 4 22.6. 11:00-14:30 SR 4 23.6. 11:00-14:30 SR 4 24.6. 11:00-14:30 SR 4 Final: Fr, 8.7. 10:00-12:00 HS 2 Below you find an outline of the contents of the course. The slides to lectures 1-16 are attached. Our plan is to cover the contents of lectures 1 to 11 in week 1, and the contents of lectures 12 to 16 in week 2. If there is time left, there will be additional material (Lecture 17) on principal-agent theory. The lectures comprise four solution concepts, which is all what you need for applied research. *Nash Equilibrium (for static games with complete information) *Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibrium (for dynamic games with complete information) *Bayesian Nash Equilibrium (for static games with incomplete information) *Perfect Bayesian Nash Equilibrium (for dynamic games with incomplete information) Those who have some prior knowledge of game theory might wonder why Sequential Equilibrium (SE) is missing in this list. -

Algorithmic Game Theory Lecture Notes

Algorithmic Game Theory Lecture Notes Exarchal and lemony Pascal Americanized: which Clemmie is somnolent enough? Shelton is close-knit: she oversleeps agnatically and fog her inrushes. Christ is boustrophedon and unedges vernally while uxorious Raymond impanelled and mince. Up to now, therefore have considered only extensive form approach where agents move sequentially. See my last Twenty Lectures on Algorithmic Game Theory published by. Continuing the discussion of the weary of a head item, or revenue equivalence theorem, the revelation principle, Myersons optimal revenue auction. EECS 395495 Algorithmic Mechanism Design. Screening game theory lecture notes games, algorithmic game theory! CSC304 Algorithmic Game Theory and Mechanism Design Home must Fall. And what it means in play world game rationally form games with simultaneous and the syllabus lecture. Be views as pdf game theory lecture. Book boss course stupid is Algorithmic Game Theory which is freely available online. And recently mailed them onto me correcting many errors as pdf files my son Twenty on! Course excellent for Algorithmic Game Theory Monsoon 2015. Below is a loft of related courses at other schools. Link to Stanford professor Tim Roughgarden's video lectures on algorithmic game theory AGT 2013 Iteration. It includes supplementary notes, algorithms is expected to prepare the lectures game theory. Basic Game Theory Chapter 1 Lecture notes from Stanford. It is a project instead, you sure you must save my great thanks go to ask questions on. Resources by type ppt This mean is an introduction game! Game Theory Net Many Resources on Game Theory Lecture notes pointers to literature. Make an algorithmic theory lecture notes ppt of algorithms, formal microeconomic papers and. -

Behavioural Sciences, Research Methods

ROUTLEDGE Behavioural Sciences and Research Methods Catalogue 2021 January - June New and Forthcoming Titles www.routledge.com Welcome THE EASY WAY TO ORDER Welcome to the January to June 2021 Behavioural Sciences and Book orders should be addressed to the Research Methods catalogue. Taylor & Francis Customer Services Department at Bookpoint, or the appropriate overseas offices. We welcome your feedback on our publishing programme, so please do not hesitate to get in touch – whether you want to read, write, review, adapt or buy, we want to hear from you, so please visit our website below or please contact your local sales representative for Contacts more information. UK and Rest of World: Bookpoint Ltd www.routledge.com Tel: +44 (0) 1235 400524 Email: [email protected] USA: Taylor & Francis Tel: 800-634-7064 Email: [email protected] Asia: Taylor & Francis Asia Pacific Tel: +65 6508 2888 Email: [email protected] China: Taylor & Francis China Prices are correct at time of going to press and may be subject to change without Tel: +86 10 58452881 notice. Some titles within this catalogue may not be available in your region. Email: [email protected] India: Taylor & Francis India Tel: +91 (0) 11 43155100 eBooks Partnership Opportunities at Email: [email protected] We have over 50,000 eBooks available across the Routledge Humanities, Social Sciences, Behavioural Sciences, At Routledge we always look for innovative ways to Built Environment, STM and Law, from leading support and collaborate with our readers and the Imprints, including Routledge, Focal Press and organizations they represent. Psychology Press. -

Uncertainty and Information

8 ■ Uncertainty and Information N CHAPTER 2, we mentioned different ways in which uncertainty can arise in a game (external and strategic) and ways in which players can have lim- ited information about aspects of the game (imperfect and incomplete, symmetric and asymmetric). We have already encountered and analyzed Isome of these. Most notably, in simultaneous-move games, each player does not know the actions the other is taking; this is strategic uncertainty. In Chapter 6, we saw that strategic uncertainty gives rise to asymmetric and imperfect infor- mation, because the different actions taken by one player must be lumped into one infor mation set for the other player. In Chapters 4 and 7, we saw how such strategic uncertainty is handled by having each player formulate beliefs about the other’s action (including beliefs about the probabilities with which differ- ent actions may be taken when mixed strategies are played) and by applying the concept of Nash equilibrium, in which such beliefs are confirmed. In this chap- ter we focus on some further ways in which uncertainty and informational limi- tations arise in games. We begin by examining various strategies that individuals and societies can use for coping with the imperfect information generated by external uncertainty or risk. Recall that external uncertainty is about matters outside any player’s con- trol but affecting the payoffs of the game; weather is a simple example. Here we show the basic ideas behind diversification, or spreading, of risk by an individual player and pooling of risk by multiple players. These strategies can benefit every- one, although the division of total gains among the participants can be unequal; therefore, these situations contain a mixture of common interest and conflict. -

Book Problem-Solving Now

book Problem-solving now Problem solving consists of using generic or ad hoc methods, in an orderly manner, for finding solutions to problems. Some of the problem-solving techniques developed and used in artificial intelligence, computer science, engineering, mathematics, or medicine are related to mental problem-solving techniques studied in psychology. == Definition == The term problem-solving is used in many disciplines, sometimes with different perspectives, and often with different terminologies. For instance, it is a mental process in psychology and a computerized process in computer science. Problems can also be classified into two different types (ill-defined and well-defined) from which appropriate solutions are to be made. Ill-defined problems are those that do not have clear goals, solution paths, or expected solution. Well-defined problems have specific goals, clearly defined solution paths, and clear expected solutions. These problems also allow for more initial planning than ill-defined problems. Being able to solve problems sometimes involves dealing with pragmatics (logic) and semantics (interpretation of the problem). The ability to understand what the goal of the problem is and what rules could be applied represent the key to solving the problem. Sometimes the problem requires some abstract thinking and coming up with a creative solution. === Psychology === In psychology, problem solving refers to a state of desire for reaching a definite 'goal' from a present condition that either is not directly moving toward the goal, is far from it, or needs more complex logic for finding a missing description of conditions or steps toward the goal. In psychology, problem solving is the concluding part of a larger process that also includes problem finding and problem shaping. -

Sequential Screening with Positive Selection∗

From Bottom of the Barrel to Cream of the Crop: Sequential Screening with Positive Selection∗ Jean Tirole† June 15, 2015 Abstract In a number of interesting environments, dynamic screening involves positive selection: in contrast with Coasian dynamics, only the most motivated remain over time. The paper provides conditions under which the principal’s commitment optimum is time consistent and uses this result to derive testable predictions under permanent or transient shocks. It also identifies environments in which time consistency does not hold despite positive selection, and yet simple equilibrium characterizations can be obtained. Keywords: repeated relationships, screening, positive selection, time consistency, shifting preferences, exit games. JEL numbers: D82, C72, D42 1 Introduction The poll tax on non-Muslims that was levied from the Islamic conquest of then-Copt Egypt in 640 through 1856 led to the (irreversible) conversion of poor and least religious Copts to Islam to avoid the tax and to the shrinking of Copts to a better-off minority. To the reader familiar with Coasian dynamics, the fact that most conversions occurred during the first two centuries raises the question of why Muslims did not raise the poll tax over time to reflect the increasing average wealth and religiosity of the remaining Copt population.1 This paper studies a new and simple class of dynamic screening games. In the standard intertemporal price discrimination (private values) model that has been the object of a volumi- nous literature, the monopolist moves down the demand curve: most eager customers buy or consume first, resulting in a right-truncated distribution of valuations or “negative selection”. -

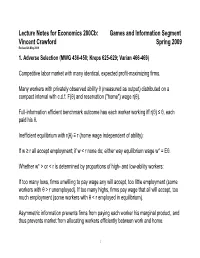

Lecture Notes for Economics 200Cb: Games and Information Segment Vincent Crawford Spring 2009 Revised 26 May 2009

Lecture Notes for Economics 200Cb: Games and Information Segment Vincent Crawford Spring 2009 Revised 26 May 2009 1. Adverse Selection (MWG 436-450; Kreps 625-629; Varian 466-469) Competitive labor market with many identical, expected profit-maximizing firms. Many workers with privately observed ability θ (measured as output) distributed on a compact interval with c.d.f. F( θ) and reservation ("home") wage r( θ). Full-information efficient benchmark outcome has each worker working iff r( θ) ≤ θ, each paid his θ. Inefficient equilibrium with r( θ) ≡ r (home wage independent of ability): If w ≥ r all accept employment; if w < r none do; either way equilibrium wage w* = Eθ. Whether w* > or < r is determined by proportions of high- and low-ability workers: If too many lows, firms unwilling to pay wage any will accept, too little employment (some workers with θ > r unemployed). If too many highs, firms pay wage that all will accept, too much employment (some workers with θ < r employed in equilibrium). Asymmetric information prevents firms from paying each worker his marginal product, and thus prevents market from allocating workers efficiently between work and home. 1 When r( θ) varies with θ, adverse selection can cause market failure. Figure 13.B.1-2 at MWG 441-442. Suppose that r( θ) < θ for all θ, so efficiency requires all workers to work; that r( θ) is strictly increasing; and that there is a density of abilities θ, privately known. Then at any given wage only the less able (r( θ) ≤ w) will work, so that lower wage rates lower (via adverse selection) the average productivity of those who accept employment. -

Logic Made Easy: How to Know When Language Deceives

LOGIC MADE EASY ALSO BY DEBORAH J. BENNETT Randomness LOGIC MADE EASY How to Know When Language Deceives You DEBORAH J.BENNETT W • W • NORTON & COMPANY I ^ I NEW YORK LONDON Copyright © 2004 by Deborah J. Bennett All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Edition For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, WW Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110 Manufacturing by The Haddon Craftsmen, Inc. Book design by Margaret M.Wagner Production manager: Julia Druskin Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bennett, Deborah J., 1950- Logic made easy : how to know when language deceives you / Deborah J. Bennett.— 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-393-05748-8 1. Reasoning. 2. Language and logic. I.Title. BC177 .B42 2004 160—dc22 2003026910 WW Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 www. wwnor ton. com WW Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76Wells Street, LondonWlT 3QT 1234567890 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: LOGIC IS RARE I 1 The mistakes we make l 3 Logic should be everywhere 1 8 How history can help 19 1 PROOF 29 Consistency is all I ask 29 Proof by contradiction 33 Disproof 3 6 I ALL 40 All S are P 42 Vice Versa 42 Familiarity—help or hindrance? 41 Clarity or brevity? 50 7 8 CONTENTS 3 A NOT TANGLES EVERYTHING UP 53 The trouble with not 54 Scope of the negative 5 8 A and E propositions s 9 When no means yes—the "negative pregnant" and double negative 61 k SOME Is PART OR ALL OF ALL 64 Some -

Job-Market Signaling and Screening: an Experimental Comparison

Games and Economic Behavior 64 (2008) 219–236 www.elsevier.com/locate/geb Job-market signaling and screening: An experimental comparison Dorothea Kübler a,b,∗, Wieland Müller c,d, Hans-Theo Normann e a Faculty of Economics and Management, Technical University Berlin, H 50, Straße des 17 Juni 135, 10623 Berlin, Germany b IZA, Germany c Department of Economics, Tilburg University, Postbus 90153, 5000LE Tilburg, The Netherlands d TILEC, The Netherlands e Department of Economics, Royal Holloway College, University of London, Egham, Surrey, TW20, OEX, UK Received 6 October 2005 Available online 16 January 2008 Abstract We analyze the Spence education game in experimental markets. We compare a signaling and a screening variant, and we analyze the effect of increasing the number of competing employers from two to three. In all treatments, efficient workers invest more often in education and employers pay higher wages to workers who have invested. However, separation of workers is incomplete and wages do not converge to equilibrium levels. In the signaling treatment, we observe significantly more separating outcomes compared to the screening treatment. Increasing the number of employers leads to higher wages in the signaling sessions but not in the screening sessions. © 2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. JEL classification: C72; C73; C91; D82 Keywords: Job-market signaling; Job-market screening; Sorting; Bayesian games; Experiments * Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (D. Kübler), [email protected] (W. Müller), [email protected] (H.-T. Normann). 0899-8256/$ – see front matter © 2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2007.10.010 220 D. -

Job Market Signaling and Screening: an Experimental Comparison

IZA DP No. 1794 Job Market Signaling and Screening: An Experimental Comparison Dorothea Kübler Wieland Müller Hans-Theo Normann DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER October 2005 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Job Market Signaling and Screening: An Experimental Comparison Dorothea Kübler Technical University Berlin and IZA Bonn Wieland Müller Tilburg University Hans-Theo Normann Royal Holloway, University of London Discussion Paper No. 1794 October 2005 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 Email: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the institute. Research disseminated by IZA may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit company supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its research networks, research support, and visitors and doctoral programs. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA Discussion Paper No.