China-North Korea Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competitiveness Analysis of China's Main Coastal Ports

2019 International Conference on Economic Development and Management Science (EDMS 2019) Competitiveness analysis of China's main coastal ports Yu Zhua, * School of Economics and Management, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing 210000, China; [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: China coastal ports above a certain size, competitive power analysis, factor analysis, cluster analysis Abstract: As a big trading power, China's main mode of transportation of international trade goods is sea transportation. Ports play an important role in China's economic development. Therefore, improving the competitiveness of coastal ports is an urgent problem facing the society at present. This paper selects 12 relevant indexes to establish a relatively comprehensive evaluation index system, and uses factor analysis and cluster analysis to evaluate and rank the competitiveness of China's 30 major coastal ports. 1. Introduction Port is the gathering point and hub of water and land transportation, the distribution center of import and export of industrial and agricultural products and foreign trade products, and the important node of logistics. With the continuous innovation of transportation mode and the rapid development of science and technology, ports play an increasingly important role in driving the economy, with increasingly rich functions and more important status and role. Meanwhile, the competition among ports is also increasingly fierce. In recent years, with the rapid development of China's economy and the promotion of "the Belt and Road Initiative", China's coastal ports have also been greatly developed. China has more than 18,000 kilometers of coastline, with superior natural conditions. With the introduction of the policy of reformation and opening, the human conditions are also excellent. -

The Tumen Triangle Documentation Project

THE TUMEN TRIANGLE DOCUMENTATION PROJECT SOURCING THE CHINESE-NORTH KOREAN BORDER Edited by CHRISTOPHER GREEN Issue Two February 2014 ABOUT SINO-NK Founded in December 2011 by a group of young academics committed to the study of Northeast Asia, Sino-NK focuses on the borderland world that lies somewhere between Pyongyang and Beijing. Using multiple languages and an array of disciplinary methodologies, Sino-NK provides a steady stream of China-DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea/North Korea) documentation and analysis covering the culture, history, economies and foreign relations of these complex states. Work published on Sino-NK has been cited in such standard journalistic outlets as The Economist, International Herald Tribune, and Wall Street Journal, and our analysts have been featured in a range of other publications. Ultimately, Sino-NK seeks to function as a bridge between the ubiquitous North Korea media discourse and a more specialized world, that of the academic and think tank debates that swirl around the DPRK and its immense neighbor. SINO-NK STAFF Editor-in-Chief ADAM CATHCART Co-Editor CHRISTOPHER GREEN Managing Editor STEVEN DENNEY Assistant Editors DARCIE DRAUDT MORGAN POTTS Coordinator ROGER CAVAZOS Director of Research ROBERT WINSTANLEY-CHESTERS Outreach Coordinator SHERRI TER MOLEN Research Coordinator SABINE VAN AMEIJDEN Media Coordinator MYCAL FORD Additional translations by Robert Lauler Designed by Darcie Draudt Copyright © Sino-NK 2014 SINO-NK PUBLICATIONS TTP Documentation Project ISSUE 1 April 2013 Document Dossiers DOSSIER NO. 1 Adam Cathcart, ed. “China and the North Korean Succession,” January 16, 2012. 78p. DOSSIER NO. 2 Adam Cathcart and Charles Kraus, “China’s ‘Measure of Reserve’ Toward Succession: Sino-North Korean Relations, 1983-1985,” February 2012. -

This Is Northeast China Report Categories: Market Development Reports Approved By: Roseanne Freese Prepared By: Roseanne Freese

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 12/30/2016 GAIN Report Number: SH0002 China - Peoples Republic of Post: Shenyang This is Northeast China Report Categories: Market Development Reports Approved By: Roseanne Freese Prepared By: Roseanne Freese Report Highlights: Home to winter sports, ski resorts, and ancient Manchurian towns, Dongbei or Northeastern China is home to 110 million people. With a down-home friendliness resonant of the U.S. Midwest, Dongbei’s denizens are the largest buyer of U.S. soybeans and are China’s largest consumers of beef and lamb. Dongbei companies, processors and distributors are looking for U.S. products. Dongbei importers are seeking consumer-ready products such as red wine, sports beverages, and chocolate. Processors and distributors are looking for U.S. hardwoods, potato starch, and aquatic products. Liaoning Province is also set to open China’s seventh free trade zone in 2018. If selling to Dongbei interests you, read on! General Information: This report provides trends, statistics, and recommendations for selling to Northeast China, a market of 110 million people. 1 This is Northeast China: Come See and Come Sell! Home to winter sports, ski resorts, and ancient Manchurian towns, Dongbei or Northeastern China is home to 110 million people. With a down-home friendliness resonant of the U.S. Midwest, Dongbei’s denizens are the largest buyer of U.S. soybeans and are China’s largest consumers of beef and lamb. Dongbei companies, processors and distributors are looking for U.S. -

Best-Performing Cities China 2017 the Nation’S Most Successful Economies

BEST-PERFORMING CITIES CHINA 2017 THE NATION’S MOST SUCCESSFUL ECONOMIES PERRY WONG, MICHAEL C.Y. LIN, AND JOE LEE TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors are grateful to Laura Deal Lacey, executive director of the Milken Institute Asia Center; Belinda Chng, the center’s director for policy and programs; Ann-Marie Eu, the Institute’s associate for communications, and Jeff Mou, the Institute’s associate, for their support in developing an edition of our Best-Performing Cities series focused on China. We thank communication teams for their support in publications, as well as Ross DeVol, the Institute’s chief research officer, and Minoli Ratnatunga, economist at the Institute, for their constructive comments on our research. ABOUT THE MILKEN INSTITUTE A nonprofit, nonpartisan economic think tank, the Milken Institute works to improve lives around the world by advancing innovative economic and policy solutions that create jobs, widen access to capital, and enhance health. We do this through independent, data-driven research, action-oriented meetings, and meaningful policy initiatives. ABOUT THE ASIA CENTER The Milken Institute Asia Center promotes the growth of inclusive and sustainable financial markets in Asia by addressing the region’s defining forces, developing collaborative solutions, and identifying strategic opportunities for the deployment of public, private, and philanthropic capital. Our research analyzes the demographic trends, trade relationships, and capital flows that will define the region’s future. ABOUT THE CENTER FOR JOBS AND HUMAN CAPITAL The Center for Jobs and Human Capital promotes prosperity and sustainable economic growth around the world by increasing the understanding of the dynamics that drive job creation and promote industry expansion. -

(Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) of Korea, with Comments and New Records

Number 404: 1-36 ISSN 1026-051X April 2020 https://doi.org/10.25221/fee.404.1 http://zoobank.org/References/C2AC80FF-60B1-48C0-A6D1-9AA4BAE9A927 AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF LEAF BEETLES (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELIDAE) OF KOREA, WITH COMMENTS AND NEW RECORDS H.-W. Cho1, *), S. L. An 2) 1) Animal & Plant Research Team, Nakdonggang National Institute of Biological Resources, 137 Donam 2-gil, Sangju 37242, Republic of Korea. *Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] 2) Division of Research, National Science Museum, 481 Daedeok-daero, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 34143, Republic of Korea. Summary. An updated list of Chrysomelidae of Korea is provided with comments on all taxonomic, nomenclatural, and distributional changes. This paper is the first attempt to divide the distributional records of all Korean Chrysomelidae into records for North and South Korea. In total, 128 genera and 424 species are reported: 293 species in North Korea, 340 in South Korea, and 10 without precise localities in Korea; 22 species are excluded from the Korean fauna; 15 new national records from South Korea are reported, 10 of which are new to Korea. Key words: Chrysomelidae, fauna, new record, taxonomy, North Korea, South Korea. Х. В. Чо, С. Л. Ан. Аннотированный список жуков-листоедов (Coleop- tera: Chrysomelidae) Кореи с замечаниями и новыми указаниями // Дальне- восточный энтомолог. 2020. N 404. С. 1-36. Резюме. Приводится обновленный список жуков-листоедов (Chrysomelidae) Кореи с таксономическим и номенклатурным изменениями и замечаниями по 1 распространению. Предпринята первая попытка разделения фаунистических данных по всем корейским листоедам на указания для северной и южной частей полуострова. Всего приводятся 424 вида из 128 родов, из которых 293 вида отмечены для Северной, 340 видов – для Южной Кореи, а 10 видов – из Кореи без более точного указания; 22 вид искючен из фауны Корейского полу- острова; 15 видов впервые указаны для Республики Корея, из них 10 видов являются новыми для полуострова. -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal

Issue No. 1044, 08 February 2013 Articles & Other Documents: Featured Article: Roll Forward the Doomsday Train 1. U.S. Ready for ‘Serious’ Direct Nuclear Iran Negotiations 2. Iran to Send Astronaut to Space by 2015 3. Iran's Nuclear Sites Impervious to any Attack: Cmdr. 4. Iran Nuclear Talks Set for Feb. 26; Signals from Tehran Mixed 5. Ayatollah Khamenei Rejects Talks with US under Pressure 6. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei Rejects chance of Direct Talks with US 7. DPRK Denounces U.S. for Double Standards on Rocket Launches 8. N. Korea Military Meeting Hints at Nuclear Test 9. Is N.Korea Planning Simultaneous Nuke Tests? 10. Concern Grows over Arms Buildup in NE Asia 11. N. Korea Internally Promoting Latest Long-Range Rocket as Ballistic Missile 12. The Anatomy of North Korea’s Nuclear Test Tunnels Released for the First Time 13. N.Korean Nuke Test 'Likely in Mid-February' 14. S. Korea Pushes for Deployment of Military Spy Satellites 15. North Korea Could Be Developing a Hydrogen Bomb 16. N. Korea Distances Itself from China, Russia Ahead of Nuke Test 17. 'No Pre-Emptive Strike Planned on N.Korea's Nuke Test Site' 18. Agni-VI all Set to Take Shape 19. Ballistic Missile Defence System to Be Tested in May 20. Despite Missile Integration, Nuke Role Unlikely for Pakistan’s JF-17 21. Russia, US May Sign a New Arms Disposal Agreement 22. Missile Sub Rejoins Russia’s Northern Fleet After Refit 23. Roll Forward the Doomsday Train 24. Heavier Bunker-Buster Bomb Ready for Combat, General Says 25. -

RCI Needs Assessment, Development Strategy, and Implementation Action Plan for Liaoning Province

ADB Project Document TA–1234: Strategy for Liaoning North Yellow Sea Regional Cooperation and Development RCI Needs Assessment, Development Strategy, and Implementation Action Plan for Liaoning Province February L2MN This report was prepared by David Roland-Holst, under the direction of Ying Qian and Philip Chang. Primary contributors to the report were Jean Francois Gautrin, LI Shantong, WANG Weiguang, and YANG Song. We are grateful to Wang Jin and Zhang Bingnan for implementation support. Special thanks to Edith Joan Nacpil and Zhuang Jian, for comments and insights. Dahlia Peterson, Wang Shan, Wang Zhifeng provided indispensable research assistance. Asian Development Bank 4 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City MPP2 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org © L2MP by Asian Development Bank April L2MP ISSN L3M3-4P3U (Print), L3M3-4PXP (e-ISSN) Publication Stock No. WPSXXXXXX-X The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Note: In this publication, the symbol “$” refers to US dollars. Printed on recycled paper 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... 10 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Baseline Assessment .................................................................................................. 3 A. -

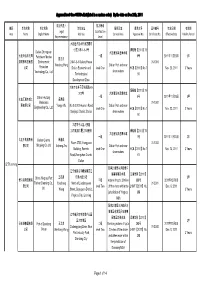

Approval Level One Osros List (Listed in a Random Order) by the Date on Dec 23Th, 2011

Approval level One OSROs List (listed in a random order) By the date on Dec 23th, 2011 法定代表人 能力等级 辖区 单位名称 英文名称 单位地址 服务区域 批准文号 证书编号 生效日期 有效期 Legal Qualification Area Name English Name Address Service Area Approval No. Certificate No. Effective Date Validity Period Representative Level 大连经济技术开发区樱花 小区24栋-1-5-1号 海船舶【2011】75 Dalian Zhongyuan 大连港及其近海水域 大连中远石化海 Petroleum Marine 一级 9号 2011年11月23日 3年 彭卫东 洋环保科技有限 Environment 24#-1-5-1 Sakura House 01-1001 Weidong Peng Dalian Port and near 公司 Protection Dalian Economic and level One HCB【2011】No.7 Nov. 23, 2011 3 Years Technology Co., Ltd. shore waters Technological 59 Development Zone 大连市甘井子区华南路9-3- 海船舶【2011】76 202号 大连港及其近海水域 Dalian Huitong 一级 0号 2011年11月23日 3年 大连汇通水域工 吴勇毅 Waterarea 01-1002 程有限公司 Yongyi Wu No.9-3-202 Huanan Road Dalian Port and near Engineering Co., Ltd. level One HCB【2011】No.7 Nov. 23, 2011 3 Years Ganjingzi District, Dalian shore waters 60 大连市中山区人民路 23号虹源大厦 2705房间 海船舶【2011】76 大连港及其近海水域 一级 1号 2011年11月23日 3年 大连千和船务有 Dalian Qianhe 朱喜成 Room 2705, Hongyuan 01-1003 限公司 Shipping Co.,Ltd Xicheng Zhu Dalian Port and near Building, Renmin level One HCB【2011】No.7 Nov. 23, 2011 3 Years shore waters Road,Zhongshan District, 61 Dalian 辽宁Liaoning 距岸20海里以内的营口 辽宁省营口市鲅鱼圈区辽 海事局辖区水域 辽海危防【2011】 China Yingcou Port 王友昌 东湾大街北段 3年 营口港清洗舱有 二级 waters of up to 20miles 398号 2011年12月8日 Tanker Cleaning Co., Youchang North of Liaodongwan 01-2001 限公司 level Two off the shore within the LHWF【2011】No. Dec. 8, 2011 Ltd. Wang Street, Bayuquan District, 3 Years jurisdiction of Yingkou 398 Yingkou City, Liaoning MSA 距岸20海里以内的丹东 港港区水域及丹东海事 辽宁省丹东市临港产业园 局辖区其他水域 辽海危防【2011】 区大东港区 3年 丹东港集团有限 Port of Dandong 王文良 二级 Dandong waters of up to 398号 2011年12月8日 Dadonggang Zone, Near 01-2002 公司 Group Wenliang Wang level Two 20miles off the shore LHWF【2011】No. -

Economic and Social Implications of China-DPRK Border Trade for China’S Northeast Region

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPLICATIONS OF CHINA -DPRK BORDER TRADE FOR CHINA ’S NORTHEAST LI DUNQIU EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This paper assesses the economic and social implications of China-DPRK border trade for China’s Northeast region. Main Argument A large portion of China’s trade with the DPRK is done through ports in China’s northeast region. This border trade has led to broader infrastructural links between the two nations, and is viewed as highly important to both China’s northeast and North Korea for the following reasons: • Border trade helps stimulate market demand and helps to revive the local economies in China’s northeast. • Border trade has played an important role in helping alleviate North Korea’s grain crisis and energy and raw materials shortages. • Border trade contributes to the security of the borderlands, especially owing to its role in easing North Korea’s commodity shortages. • Border trade has brought an unintended consequence of increasing the market awareness of North Korean border residents. This may facilitate the economic reform and opening-up of the DPRK. Policy Implications • Trade with Northeast China may help promote economic and structural reforms in North Korea, especially as North Koreans grow accustomed to practices associated with market economies. • North Korean trade may be of great benefit to China, and as North Korea’s economic recovery progresses Northeast China’s exports to the region will also expand. Introduction Economic cooperation between China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) takes such forms as trade, aid and investment, among which trade is the most important one. -

03 Seong-Hyon

International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Vol. 25, No. 1, 2016, 65–93 Why Did We Get China Wrong? Reconsidering the Popular Narrative: China will abandon North Korea* Seong-Hyon Lee Despite high hopes from Seoul and Washington, China articulated that it was not ready to “abandon” North Korea in the wake of Kim Jong-un’s nuclear test in January 2016, and that there would be slim chance of this occurring in the future. Seoul and Washington’s (so far invalidated) hopes of such were premised on China’s unusually strong anger and reaction toward North Korea’s third nuclear test in 2013. Many observers have since commented that China’s patience with its Cold War ally was finally wearing thin. With that, the narrative “China will abandon North Korea” has been the mainstay of relevant discussions in the public sphere. Given the importance of the 2013 nuclear test, this paper reviews major events in 2013 that shaped the public perception of China’s growing anger and frustration with North Korea and the potential presence of alternative explanations or counter-perspectives while scrutinizing both narratives. Finally, it establishes the interpretation that, while a series of events may have shaped the popular narrative concerning China- North Korea relations in 2013 and given the public reason to believe in changes to China’s fundamental policies, however no such actual * The examination in this paper has been in the making for the last three years. In a sense, it is a product of collective intelligence, based on numerous presentations -

North Korea Today” Describing the Way the North Korean People Live As Real As Possible

RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR NORTH KOREAN SOCIETY | http://www.goodfriends.or.kr | email:[email protected] Weekly Newsletter No.277 May 2009 [“Good Friends” desires to help the North Korean people through humanistic point of view, and publishes “North Korea Today” describing the way the North Korean people live as real as possible. We at Good Friends also hope to be a bridge between the North Korean people and the world.] ___________________________________________________________________________ [Hot Topics] How Ordinary Laborers Manage To Survive In The City Of Danchun [Danchun] A Cement Factory Located Too Far From The Markets [Danchun] Many Laborers Collapse While Operating Machinery Due To Malnutrition At A Paper Factory [Danchun] Families of Laborers Rely On Boiled Tree Bark For Sustenance At The Machinery Repair Factory [Danchun] Food Shortage Causes Many Workers To Go Absent And Delays The Production Schedule At The Probing Machine Factory [Food] Heoryung City Announces 15 Day’s Worth of Food Will Be Distributed During the Month of July Special Distribution to Disabled Veterans for the 4.25 Army Foundation Day [Economy] Potato Farming Recommended for Factories in North Hamgyong Province Hamju County’s Pig Processing Plant Wastes Public Supplies Preparing for Chairman Kim Jong-Il’s Visit Grueling Conditions at Raheung Talcum Factory, Dozens of Workers Collapse on the Job 1 [Politics] Manager of Namyang Farm Management Council in Gilju County Arrested for Graft and Corruption Re-Education Center in Jeongurrie Will Be Converted into -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Regional Overview:………………………………………………………………………1 Regime Change / Preemption Vs. Disarmament / Multilateralism: The U.S. Foreign Policy Debate Continues by Ralph A. Cossa, Pacific Forum CSIS Concerns and complaints about Washington’s Iraq policy and its broader approach toward the war on terrorism, and speculation regarding North Korea’s diplomacy dominated East Asia security dialogue during the last quarter. This time last year, the world had rallied behind the U.S. in the wake of Sept. 11. Much of that support and goodwill has dissipated. The reasons vary and are complex but two words are central to any explanation: Iraq and preemption; the latter being put forth not only in the Iraqi context but as the basis of a new national security strategy. Their long-term impact on America’s East Asian relationships remains unclear; China-U.S. relations in particular could be challenged. Equally unclear is the impact of the DPRK’s recent “smile diplomacy,” which has seen an unprecedented effort by Pyongyang simultaneously to improve relations with Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington. Meanwhile, multilateralism seems to be thriving in East Asia, both with the U.S. and without. U.S.-Japan Relations:…………………………………………………………………..13 An Oasis of Stability by Brad Glosserman, Pacific Forum CSIS It has been another peaceful quarter for U.S.-Japan relations. That the bilateral relationship could be so calm despite the tumult in international diplomacy is testimony to the strength and stability of the alliance. Prime Minister Koizumi’s surprise visit to Pyongyang and the U.S.’s full court press to get the international community to take action against Iraq have provided ample opportunities for friction.