Milton's Areopagitica and the Modern First Amendment Vincent Blasi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Identity in the Writings of John Milton

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Honors Theses Honors College Fall 12-2012 English Identity in the Writings of John Milton Hannah E. Ryan University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Ryan, Hannah E., "English Identity in the Writings of John Milton" (2012). Honors Theses. 102. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/102 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi English Identity in the Writings of John Milton by Hannah Elizabeth Ryan A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of English November 2012 ii Approved by _____________________________ Jameela Lares Professor of English _____________________________ Eric Tribunella, Chair Department of English ________________________________ David R. Davies, Dean Honors College iii Abstract: John Milton is an essential writer to the English canon. Understanding his life and thought is necessary to understanding his corpus. This thesis will examine Milton’s nationalism in several major and minor poems as well as in some of Milton’s prose. It will argue that Milton’s nationalism is difficult to trace chronologically, but that education is always essential to Milton’s national vision of England. -

Edward Jones

Edward Jones Events in John Milton’s life Events in Milton’s time JM is born in Bread Street (Dec 9) 1608 Shakespeare’s Pericles debuts to and baptized in the church of All great acclaim. Hallows, London (Dec 20). Champlain founds a colony at Quebec. 1609 Shakespeare’s Cymbeline is performed late in the year or in the first months of 1610, most likely indoors at the Blackfriars Theatre. The British establish a colony in Bermuda. Moriscos (Christianized Muslims) are expelled from Spain. Galileo constructs his first telescope. The Dutch East India Company ships the first tea to Europe. A tax assessment (E179/146/470) 1610 Galileo discovers the four largest confirms the Miltons residing in moons of Jupiter (Jan 7). the parish of All Hallows, London Ellen Jeffrey, JM’s maternal 1611 Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale is grandmother, is buried in All performed at the Globe Theatre Hallows, London (Feb 26). (May). The Authorized Version (King James Bible) is published. Shakespeare’s The Tempest is performed at court (Nov 1). The Dutch begin trading with Japan. The First Presbyterian Congregation is established at Jamestown. JM’s sister Sara is baptized (Jul 15) 1612 Henry, Prince of Wales, dies. and buried in All Hallows, London Charles I becomes heir to the (Aug 6). throne. 1613 A fire breaks out during a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry VIII and destroys the Globe Theatre (Jun 29). 218 Select Chronology Events in John Milton’s life Events in Milton’s time JM’s sister Tabitha is baptized in 1614 Shakespeare’s Two Noble Kinsmen All Hallows, London (Jan 30). -

John Milton's Influence on Poets, Writers and Composers of His

John Milton’s Influence on Poets, Writers and Composers of His Period and Aftermath 1 Mehmet Recep TAŞ, Erdinç Durmuş INFO ABSTRACT ARTICLEAvailable Online September 2014 John Milton is doubtless one of the most important and influential poets Key words: nglish Language and Literature. He has always been a major Milton; influence in literature both during his lifetime and after his death. His Poetry; reputationin E among the readers and the poets is a known fact since it has Pamphlet; been proven that several writers and poets frequently wrote under the influence of this great epic poet. Milton was an artist who had written about various subjects, he was both a poet and a renowned prose writer. English Literature. As he had something to say about every field of life his admirers and followers were not necessarily from just one category. Many people, including politicians, poets, writers, composers found something valuable in Milton and his works. The purpose of this article is to reevaluate Milton’s controversial works and lay down the influence of Milton on the mentioned figures of the period and aftermath. " Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour:, – Wordsworth- It is interesting that John Milton first bec England hath need of thee." However, this kind of reputation was not something to be envied of as he soon happened to be known a ame a famous figureattracted in Englanda great deal through of attenti his ondivorce at that pamphlets. time. It is known that Milton's reputation and influence was not as great in his lifetime as it was after his death. -

John Milton, Areopagitica (1644)1

1 Primary Source 7.6 – Milton JOHN MILTON, AREOPAGITICA (1644)1 John Milton (1608–74) is widely considered the greatest writer in English after Shakespeare. A private tutor, an excellent school in London, seven years at Cambridge University, and six years of self-directed study made him an extraordinarily learned man with fluency in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Spanish, and Italian; vast knowledge of modern writing; and intimate familiarity with the literature and thought of ancient Greece and Rome, of late antiquity, and of the Middle Ages. From an early age, he believed himself destined to contribute a great creative work, something that would do credit to the gifts with which the Lord had endowed him. A deeply believing Christian and an unwavering advocate of religious, civil, and political liberty, he devoted those gifts for twenty years to the service of the Puritan and Republican causes. During this era, he penned Areopagitica, probably the greatest polemical defense of the freedom of the press ever written. Following the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660, Milton had to withdraw from political life. Seven years later, he published his masterwork, Paradise Lost, an epic poem recounting the Biblical story of the Fall of Man in over 10,000 lines of blank verse. In Areopagitica, Milton deploys impassioned arguments, vast historical knowledge, extraordinary erudition, and powerful logic to demand the abrogation of a law of 1643 authorizing twenty licensors, or censors, in England to approve or reject book and pamphlet manuscripts before publication, a general policy (not always strictly enforced) dating to the mid-1500s but abolished in 1641 by the Long Parliament. -

Censorship As a Typographical Chimera

Preliminary Communication UDC 070.13:808.5Milton, J. Received December 29th, 2009 Béla Mester Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Institute for Philosophical Research, Etele út 59-61, HU–1119 Budapest [email protected] Censorship as a Typographical Chimera John Milton and John Locke on Gestures1 Abstract The aim of my paper is to show some elements in Milton’s and Locke’s political writin gs, depending on their attitudes to different media. Milton in his argumentation against censorship must demonstrate that all the ancient instances for censorship, usually cited in his century, can be interpreted as examples of another phenomenon. However, Milton, analysing loci of Plato’s Republic and some Scriptural topics, recognises the scope and significance of nonconceptual, nonprinted, nonverbal forms of communication; he des cribes them as signs of childish, female or uneducated behaviours, as valueless phenomena from the point of view of political liberty incarnated in the freedom of press. John Locke’s attitude is the same. I will show a chain of ideas, similar to Milton’s one, in his Two Tracts on Government and in his Epistola de tolerantia, focusing the analyses on the concept of adiaphora (indifferent things). Key words censorship, orality, typographical age, Plato on censorship, adiaphora, John Milton’s Areo pagitica, John Locke’s Epistola de tolerantia The main topic of my presentation is John Milton’s argumentation and art of rhetoric in his Areopagitica. However, Milton was not a researcher of the media, and his aim in his booklet was not an analysis of homo typographicus’ thought on the freedom of thought itself, depended on the medium of the printed book; his thinking inevitably met the links between our ideals on the freedom of thought and different media by which we express them. -

The Public Sphere and the Emergence of Copyright: Areopagitica, the Stationers’ Company, and the Statute of Anne*

The Public Sphere and the Emergence of Copyright: Areopagitica, the Stationers’ Company, and the Statute of Anne* Mark Rose† I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 123 II. HABERMAS AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE .............................................. 124 III. AREOPAGITICA .................................................................................. 128 IV. THE EARLY MODERN STATIONERS’ COMPANY ................................ 132 V. THE STATUTE OF ANNE ..................................................................... 136 VI. THE “HOLLOWING OUT” OF THE PUBLIC SPHERE ............................ 139 I. INTRODUCTION The notion of the public sphere, or more precisely the bourgeois public sphere, associated with German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, has become ubiquitous in eighteenth-century cultural studies. Scholars concerned with media and democratic discourse have also invoked Habermas. Nonetheless, the relationship between the emergence of the public sphere and the emergence of copyright in early modern England has not been much discussed. In this Article, I will explore the relationship between the Habermasian public sphere and the inauguration 1 of modern copyright law in the Statute of Anne in 1710. * This Article will also appear in PRIVILEGE AND PROPERTY: ESSAYS ON THE HISTORY OF COPYRIGHT (Ronan Deazley, Martin Kretschmer, and Lionel Bently eds., forthcoming 2010). † © 2009 Mark Rose. Mark Rose (AB Princeton, BLitt Oxford, PhD Harvard) is Professor Emeritus at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he has taught in the English Department since 1977. He has also held positions at Yale, the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and the University of California, Irvine. Authors and Owners, his study of the emergence of copyright in eighteenth-century England, was a finalist for a National Book Critics’ Circle Award. Rose also regularly serves as a consultant and expert witness in matters involving allegations of copyright infringement. -

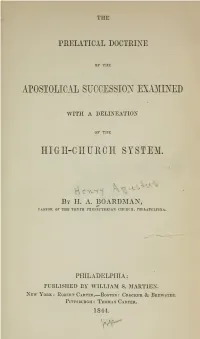

The Prelatical Doctrine of the Apostolical

THE PRELATICAL DOCTRINE APOSTOLIC.\L SUCCESSION EX^OimED WITH A DELINEATION HIGH-CHUECH SYSTEM. c Vj^"^ ^c-K-^^ ^% jlS-^ By H. a. BOARDMAN, Pastor of the te.\tii phesbyterias cuurcu, piiiLADELrniA. PHILADELPHIA: PUBLISHED BY WILLIAM S. MARTIEN. New York : Robert Carter.—Boston : Crocker So Brewster. Pittsburgh: Thomas Carter. 1S44. '^<^ Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1844, by William S. Martien, in the Office of the Clerk of the District Court of tlie Eastern District of Pennsylvania. — CONTENTS. PAOE Preface, . » 5 CHAPTER I. Hk.u-Church Pretensions ... 13 CHAPTER ir. Statement of the Question, ^9 CHAPTER III. The Argument from Scripture, , . 3o CHAPTER IV. The Historical Argument, 99 CHAPTER V. The Succession tested by facts, 170 CHAPTER VI. The True Succession, 182 CHAPTER VII. Characteristics and Tendencies of the High-Church Sys- tem : The Rule of Faith, 224 — 4 CONTENTS. CHAPTER VIII. PAGE The Church put in Christ's place, 249 CHAPTER IX. The System at variance with the general tone of the New Testament, 263 CHAPTER X. Tendency of the System to aggrandize the Prelatical Clergy : and to substitute a ritual religion for, true Christianity, 273 CHAPTER XI. Intolerance of the System, 232 CHAPTER XII. The Schismatical tendency' of the System, 321 CHAPTER XIII. Aspect of the System towards iNauiRiNG Sinners,—Conclu- sion, 334 PEEEACE. 1 MAKE no apology for \ATiting a book on the Prelatical controversy. Matters have reached such a pass that Non-Episcopahans must either defend themselves, or submit to be extruded from the house of God. The High-Church party have come into the Church of Christ, where we and our fathers have been for ages, and gravely undertaken to partition it off among themselves and the corrupt Romish and Ori- ental Hierarchies. -

Schreyer Honors College Department of English John

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH JOHN MILTON’S DIVORCE TRACTS AND GENDER EQUALITY IN FAMILY LAW MADISON V. SOPIC Spring 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Marcy North Associate Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Lisa Sternlieb English Honors Advisor Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT In recent years, John Milton’s divorce tracts have been deemed predictive of modern divorce laws. Moreover, with a new wave of feminist criticism appearing in the 1970s, such critics as Catherine Gimelli Martin, Gina Hausknecht, Maria Magro, and Harvey Couch have asserted that Milton’s divorce tracts are not only predictive, but that they promote the rights of women in divorce law in a way that has made Milton nearly prophetic. However, this thesis disputes the idea that Milton is supportive of modern gender equality within his divorce tracts, and asks such questions as: Does Milton attempt to gain an equal opportunity to divorce for both genders in his work? Does he desire divorce for the betterment of both spouses? And, finally, does Milton offer women any protection following a divorce? These questions are answered by means of closely examining Milton’s primary text, as well as multiple historical variables, such as religion, language, societal norms, and common outcomes of divorce for women. Through an examination of these factors, it is ultimately deciphered that Milton is not supportive of gender equality in divorce law, and thus, his divorce tracts are not predictive of modern divorce legislation. -

LIBERTY AS PRO-GRESSION: a STUDY of the REVOLUTIONS IDEALIZED in AREOPAGITICA, the MARRIAGE of HEAVEN and HELL and the MATRIX B

LIBERTY AS PRO-GRESSION: A STUDY OF THE REVOLUTIONS IDEALIZED IN AREOPAGITICA, THE MARRIAGE OF HEAVEN AND HELL AND THE MATRIX by Adalberto Teixeira de Andrade Rocha A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras: Estudos Literários Faculdade de Letras Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my Professor and adviser Luiz Fernando Ferreira Sá, for bringing my attention to literature in the first place through the works of John Milton. Thank you for helping me realize what it means to read. To my mother, for the example of commitment and hard work; and for her life-long dedication to my sister and I. Special thanks for putting up with me for yet one more year as I returned home for the writing of this thesis. To my father, for all the support and for always believing in me. Thank you for helping me keep all sorts of things into perspective and my priorities straight. To my great friends Fernando Barboza, Leda Edna and Eddie Aragão, not only for your endless hospitality, but for your sincere friendship and presence during both the difficult and great moments. In my distance from home, I have found one in all three of you. To Miriam Mansur, who has helped me in more ways than one during the writing of this thesis. Abstract Impressions of truth and liberty are time and space specific. Historically, works of art stand as material manifestations of the physical conversions required by ideologies in their “hailings” of individuals and reminders of those individuals’ statuses as always-already subjects. -

The Senses and Human Nature in a Political Reading of Paradise Lost

Chapter 8 The Senses and Human Nature in a Political Reading of Paradise Lost Jens Martin Gurr Milton, so far as I know, is the first to turn to the story of the Fall to explain the failure of a revolution.1 Introduction Let us begin with what seems a politically inconspicuous passage on the five senses. Here is Adam, lecturing Eve on reason, fancy and the senses: But know that in the soul Are many lesser faculties that serve Reason as chief; among these fancy next Her office holds; of all external things, Which the five watchful senses represent, She forms imaginations, airy shapes, Which reason joining or disjoining, frames All what we affirm or what deny, and call Our knowledge or opinion [. .].2 What we find here is a rather standard early modern understanding of the relationship between reason, fancy and the senses.3 But what is illuminating is the way in which this discussion is metaphorically politicized by means of the body politic analogy: the relations among the inner faculties, as so often in Milton, are rendered in the political terminology of rule, domination and 1 Hill Ch., Milton and the English Revolution (London: 1977) 352. 2 Milton John, Paradise Lost, ed. Fowler A., 2nd ed. (London: 1998) V, 100–108. Further refer- ences by book and verse will be to this edition. 3 For this as ‘a fairly straightforward account of Aristotelian faculty psychology’, cf. Moshenska J., “ ‘Transported Touch’: The Sense of Feeling in Milton’s Eden”, English Literary History 79, 1 (2012) 1–31, 24, n. -

John Milton, Areopagitica (1644)1

1 Primary Source 10.3 – Milton JOHN MILTON, AREOPAGITICA (1644)1 John Milton (1608–74) is widely considered the greatest writer in English after Shakespeare. A private tutor, an excellent school in London, seven years at Cambridge University, and six years of self-directed study made him an extraordinarily learned man with fluency in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Spanish, and Italian; vast knowledge of modern writing; and intimate familiarity with the literature and thought of ancient Greece and Rome, of late antiquity, and of the Middle Ages. From an early age, he believed himself destined to contribute a great creative work, something that would do credit to the gifts with which the Lord had endowed him. A deeply believing Christian and an unwavering advocate of religious, civil, and political liberty, he devoted those gifts for twenty years to the service of the Puritan and Republican causes. During this era, he penned Areopagitica, probably the greatest polemical defense of the freedom of the press ever written. Following the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660, Milton had to withdraw from political life. Seven years later, he published his masterwork, Paradise Lost, an epic poem recounting the Biblical story of the Fall of Man in over 10,000 lines of blank verse. In Areopagitica, Milton deploys impassioned arguments, vast historical knowledge, extraordinary erudition, and powerful logic to demand the abrogation of a law of 1643 authorizing twenty licensors, or censors, in England to approve or reject book and pamphlet manuscripts before publication, a general policy (not always strictly enforced) dating to the mid-1500s but abolished in 1641 by the Long Parliament. -

John Milton and the Spirit of Capitalism Eliot Davila University of Maryland College Park, Maryland

The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English Volume 12 | Issue 1 Article 4 2010 John Milton and the Spirit of Capitalism Eliot Davila University of Maryland College Park, Maryland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor Part of the Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Davila, Eliot (2010) "John Milton and the Spirit of Capitalism," The Oswald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor/vol12/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you by the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The sO wald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John Milton and the Spirit of Capitalism Keywords Capitalism, John Milton, British Literatue This article is available in The sO wald Review: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Criticism in the Discipline of English: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor/vol12/iss1/4 21 John Milton and the Spirit of Capitalism Eliot Davila University of Maryland College Park, Maryland n The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max IWeber assigns the following task to his readers: Consider, for example, the conclusion of the Divine Comedy, where the poet in Paradise is struck dumb as, all desires fulfilled, he contemplates the divine mysteries.