Shaoxing Wine Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beverages Swiggity Swag

Beverages Non-Alcoholic can/bottle/carton 1. Guava Drink ........................................................ $3 2. Grass Jelly .......................................................... $3 3. Lychee Nectar ..................................................... $3 4. Chrysanthemum Tea ........................................... $3 5. Aloe .................................................................... $3 6. Ito-en green tea .................................................. $3 7. Mr. Brown Coffee................................................ $3 8. Yakult Yogurt Probiotic Drink (6) ....................... $3 Booze 1. Golden Flower ..................................................... $10 Blended non-peated scotch, chrysanthemum tea, honey, lemon oil 2. Duck Sauce ......................................................... $10 Tequila, Sichuan peppercorn, peach, lemon EAT! MORE! MORE! EAT! 3. Taking a Bath in New York ................................. $10 Vodka, cassis, orange bitters, orange oil 4. 20th Century ....................................................... $10 Gin, cacao, Cocchi Americano, lemon shifu takeout certified professional professional certified takeout shifu 5. I’m gonna Baijiu .................................................. $10 m.d. esq. ph.d danger lucky sir sir lucky danger ph.d esq. m.d. Baijiu, bourbon, cardamom, urepan 6. Sloop Juice Bomb (IPA) ....................................... $6 open hours hours open 7. Victory Prima Pils (Pilsner) ................................. $6 served first come first -

Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.181699 Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China Appendix Appendix Table. Surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitals, Zhejiang Province, China, 2015– 2017* Years Hospitals by city Level† Strain identification method‡ excluded§ Hangzhou First 17 People's Liberation Army Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou First People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Hangzhou Children's Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Hospital of Chinese Traditional Hospital 3A Phoenix 100, VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Cancer Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou 3A VITEK 2 Compact Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A VITEK 2 Compact The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of 3A MALDI-TOF MS Medicine Hangzhou Second People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, Hangzhou 3A Phoenix 100 Xinhua Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Cancer -

Domestic and International Challenges for the Textile Industry in Shaoxing (Zhejiang)

Special feature China perspectives Domestic and International Challenges for the Textile Industry in Shaoxing (Zhejiang) SHI LU ABSTRACT: This article recounts the transformations that have taken place in the textile industry in Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, over the course of the past 30 years. It reveals the importance of the local setup and the links that have built up between companies, mar - kets, and the state and its departments. It also exposes the difficulties experienced by companies as they try to adapt to their changing environment, whether in terms of opportunities offered by the domestic or international markets, or new regulations. KEYWORDS: textile industry, clusters, developmental state, governance, market. Introduction markets increased, the cost of labour rose, and new environmental require - ments were imposed. This contribution looks back over the transformations he developmental state concept was developed by Chalmers Johnson and the ways in which companies have adapted to these changes in the in the early 1980s to describe the role of the state in the economic case of the textile industry in Zhejiang Province and, more particularly, in successes enjoyed by Japan, which he considered to have been un - the city of Shaoxing. T (1) derestimated. It was subsequently used to refer to the ability of economic In 2013, 15% of companies in Zhejiang Province were operating in the bureaucracies to guide development in South Korea and Taiwan, channelling textile and clothing industries, making it one of China’s main centres for private investment towards growth sectors and allowing these economies manufacturing textile products at that time. (4) The city of Shaoxing, a for - to benefit from a comparative advantage in international competition. -

Investigating the Relationship Between Kadazandusun Beliefs About Paddy Spirits, Riddling in Harvest-Time and Paddy-Related Sundait

VOL. 13 ISSN 1511-8393 JULAI/JULY 2012 http://www.ukm.my/jmalim/ Investigating the Relationship between Kadazandusun Beliefs about Paddy Spirits, Riddling in Harvest-time and Paddy-Related Sundait (Perkaitan antara Kepercayaan terhadap Semangat Padi, Berteka-teki pada Musim Menuai dan Sundait Kadazandusun yang Berunsurkan Padi: Satu Penelitian) LOW KOK ON Sekolah Pengajian Seni, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Jalan UMS, 88400 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah [email protected] LEE YOK FEE Jabatan Pengajian Kenegaraan dan Ketamadunan Fakulti Ekologi Manusia, Universiti Putra Malaysia 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor [email protected] ABSTRACT During recent field trips to collect sundait (riddles) from Kadazandusun communities in Sabah, it was noted that many of the riddle answers relate to paddy farming: for example, rice planting activities and related paraphernalia are often mentioned. This paper analyzes collected Kadazandusun “paddy- related” sundait based on their social context and background. In addition, it also examines traditional beliefs in paddy spirits and the origin of riddling at harvest-time. Some unique aspects of paddy-related sundait are highlighted and the relationship between the belief in paddy spirits and the ritual of harvest riddling is further explored. Keywords: Kadazandusun sundait, paddy-related riddles, paddy spirits, harvest- time riddling 72 | MALIM – SEA Journal of General Studies 13 • 2012 ABSTRAK Dalam beberapa kerja lapangan mengumpul sundait (teka-teki) Kadazandusun di Sabah yang telah pengkaji lakukan baru-baru ini, banyak sundait Kadazandusun yang jawapannya berkait dengan unsur padi, aktiviti penanaman padi dan alatan padi telah dikenal pasti. Fokus tulisan ini adalah menganalisis koleksi sundait Kadazandusun yang berunsurkan padi berasaskan konteks dan latar sosial orang Kadazandusun. -

Inscriptional Records of the Western Zhou

INSCRIPTIONAL RECORDS OF THE WESTERN ZHOU Robert Eno Fall 2012 Note to Readers The translations in these pages cannot be considered scholarly. They were originally prepared in early 1988, under stringent time pressures, specifically for teaching use that term. Although I modified them sporadically between that time and 2012, my final year of teaching, their purpose as course materials, used in a week-long classroom exercise for undergraduate students in an early China history survey, did not warrant the type of robust academic apparatus that a scholarly edition would have required. Since no broad anthology of translations of bronze inscriptions was generally available, I have, since the late 1990s, made updated versions of this resource available online for use by teachers and students generally. As freely available materials, they may still be of use. However, as specialists have been aware all along, there are many imperfections in these translations, and I want to make sure that readers are aware that there is now a scholarly alternative, published last month: A Source Book of Ancient Chinese Bronze Inscriptions, edited by Constance Cook and Paul Goldin (Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China, 2016). The “Source Book” includes translations of over one hundred inscriptions, prepared by ten contributors. I have chosen not to revise the materials here in light of this new resource, even in the case of a few items in the “Source Book” that were contributed by me, because a piecemeal revision seemed unhelpful, and I am now too distant from research on Western Zhou bronzes to undertake a more extensive one. -

Maria Khayutina • [email protected] the Tombs

Maria Khayutina [email protected] The Tombs of Peng State and Related Questions Paper for the Chicago Bronze Workshop, November 3-7, 2010 (, 1.1.) () The discovery of the Western Zhou period’s Peng State in Heng River Valley in the south of Shanxi Province represents one of the most fascinating archaeological events of the last decade. Ruled by a lineage of Kui (Gui ) surname, Peng, supposedly, was founded by descendants of a group that, to a certain degree, retained autonomy from the Huaxia cultural and political community, dominated by lineages of Zi , Ji and Jiang surnames. Considering Peng’s location right to the south of one of the major Ji states, Jin , and quite close to the eastern residence of Zhou kings, Chengzhou , its case can be very instructive with regard to the construction of the geo-political and cultural space in Early China during the Western Zhou period. Although the publication of the full excavations’ report may take years, some preliminary observations can be made already now based on simplified archaeological reports about the tombs of Peng ruler Cheng and his spouse née Ji of Bi . In the present paper, I briefly introduce the tombs inventory and the inscriptions on the bronzes, and then proceed to discuss the following questions: - How the tombs M1 and M2 at Hengbei can be dated? - What does the equipment of the Hengbei tombs suggest about the cultural roots of Peng? - What can be observed about Peng’s relations to the Gui people and to other Kui/Gui- surnamed lineages? 1. General Information The cemetery of Peng state has been discovered near Hengbei village (Hengshui town, Jiang County, Shanxi ). -

Trends and Correlates of High-Risk Alcohol

Advance Publication by J-STAGE Journal of Epidemiology Original Article J Epidemiol 2019 Trends and Correlates of High-Risk Alcohol Consumption and Types of Alcoholic Beverages in Middle-Aged Korean Adults: Results From the HEXA-G Study Jaesung Choi1, Ji-Yeob Choi1,2,3, Aesun Shin2,3, Sang-Ah Lee4, Kyoung-Mu Lee5, Juhwan Oh6, Joo Yong Park1, Jong-koo Lee6,7, and Daehee Kang1,2,3,8 1Department of Biomedical Sciences, Seoul National University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea 2Department of Preventive Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea 3Cancer Research Institute, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea 4Department of Preventive Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Kangwon, Korea 5Department of Environmental Health, College of Natural Science, Korea National Open University, Seoul, Korea 6JW Lee Center for Global Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea 7Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea 8Institute of Environmental Medicine, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul, Korea Received November 30, 2017; accepted February 28, 2018; released online August 25, 2018 ABSTRACT Background: We aimed to report the prevalence and correlates of high-risk alcohol consumption and types of alcoholic beverages. Methods: The baseline data of the Health Examinees-Gem (HEXA-G) study participants, including 43,927 men and 85,897 women enrolled from 2005 through 2013, were used for analysis. Joinpoint regression was performed to estimate trends in the age-standardized prevalence of alcohol consumption. Associations of demographic and behavioral factors, perceived health- related effects, social relationships, and the diagnostic history of diseases with alcohol consumption were assessed using multinomial logistic regression. -

Piece Mold, Lost Wax & Composite Casting Techniques of The

Piece Mold, Lost Wax & Composite Casting Techniques of the Chinese Bronze Age Behzad Bavarian and Lisa Reiner Dept. of MSEM College of Engineering and Computer Science September 2006 Table of Contents Abstract Approximate timeline 1 Introduction 2 Bronze Transition from Clay 4 Elemental Analysis of Bronze Alloys 4 Melting Temperature 7 Casting Methods 8 Casting Molds 14 Casting Flaws 21 Lost Wax Method 25 Sanxingdui 28 Environmental Effects on Surface Appearance 32 Conclusion 35 References 36 China can claim a history rich in over 5,000 years of artistic, philosophical and political advancement. As well, it is birthplace to one of the world's oldest and most complex civilizations. By 1100 BC, a high level of artistic and technical skill in bronze casting had been achieved by the Chinese. Bronze artifacts initially were copies of clay objects, but soon evolved into shapes invoking bronze material characteristics. Essentially, the bronze alloys represented in the copper-tin-lead ternary diagram are not easily hot or cold worked and are difficult to shape by hammering, the most common techniques used by the ancient Europeans and Middle Easterners. This did not deter the Chinese, however, for they had demonstrated technical proficiency with hard, thin walled ceramics by the end of the Neolithic period and were able to use these skills to develop a most unusual casting method called the piece mold process. Advances in ceramic technology played an influential role in the progress of Chinese bronze casting where the piece mold process was more of a technological extension than a distinct innovation. Certainly, the long and specialized experience in handling clay was required to form the delicate inscriptions, to properly fit the molds together and to prevent them from cracking during the pour. -

![Directors and Parties Involved in the [Redacted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7098/directors-and-parties-involved-in-the-redacted-577098.webp)

Directors and Parties Involved in the [Redacted]

THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THAT THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT DIRECTORS AND PARTIES INVOLVED IN THE [REDACTED] DIRECTORS Name Address Nationality Executive Directors Mr. Hua Bingru (華丙如) 7-6, Building 7 Chinese Jinchongfu Lanting Community Yuhang Economic Development Zone Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province the PRC Mr. Wang Shijian (王詩劍) Room 2101, Unit 2, Building 4 Chinese Zanchengtanfu, Xinyan Road Meiyan Community Donghu Street, Yuhang District Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province the PRC Mr. Wang Weiping (汪衛平) Room 802, Unit 3, Building 6 Chinese Junlin Tianxia City Community Shidai Community Nanyuan Street, Yuhang District Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province the PRC Mr. Dong Zhenguo (董振國) Paiwu 39-2 Chinese Jindu Xiagong Community Maoshan Community Donghu Street, Yuhang District Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province the PRC Mr. Xu Shijian (徐石尖) Room 702, Unit 2, Building 7 Chinese Mingshiyuan Community Renmin Dadao Baozhangqiao Community Nanyuan Street, Yuhang District Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province the PRC –80– THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THAT THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT DIRECTORS AND PARTIES INVOLVED IN THE [REDACTED] Name Address Nationality Non-executive Directors Ms. Hua Hui (華慧) Room 101, Unit 1, Building 25 Chinese Beizhuyuan, Xiagong Huayuan 156 Beisha West Road Maoshan Community Linping Street, Yuhang District Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province the PRC Independent non-executive Directors Mr. Yu Kefei (俞可飛) Room 1201, Unit 1, Building 5 Chinese Binjiang Huadu No. -

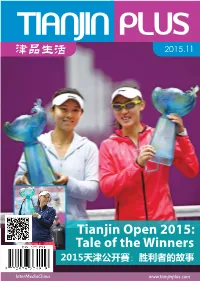

Tianjin Open 2015: Tale of the Winners 2015天津公开赛:胜利者的故事

2015.082015.082015.08 Tianjin Open 2015: Tale of the Winners 2015天津公开赛:胜利者的故事 InterMediaChina www.tianjinplus.com IST offers your children a welcoming, inclusive international school experience, where skilled and committed teachers deliver an outstanding IB education in an environment of quality learning resources and world-class facilities. IST is... fully accredited by the Council of International Schools (CIS) IST is... fully authorized as an International Baccalaureate World School (IB) IST is... fully accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) IST is... a full member of the following China and Asia wide international school associations: ACAMIS, ISAC, ISCOT, EARCOS and ACMIBS 汪正影像艺术 VISUAL ARTS Wang Zheng International Children Photography Agency 汪 正·天 津 旗下天津品牌店 ■婴有爱婴幼儿童摄影 ■韩童街拍工作室 ■顽童儿童摄影会馆 ■汪叔叔专业儿童摄影 ■素摄儿童摄影会馆 转 Website: www.istianjin.org Email: [email protected] Tel: 86 22 2859 2003/5/6 ■ Prince&Princess 摄影会馆 ■韩爱儿童摄影会馆 ■本真儿童摄影会馆 4006-024-521 5 NO.22 Weishan South Road, Shuanggang, Jinnan District, Tianjin 300350, P.R.China 14 2015 2015 CONTENTS 11 CONTENTS 11 Calendar 06 Beauty 38 46 Luscious Skin Sport & Fitness 40 Partner Promotions 09 Tianjin Open 2015: A Tale of Upsets, Close Calls and Heroic Performances Art & Culture 14 How to 44 Eat me. Tianjin style. How to Cope with Missing Home Feature Story 16 Beijing Beat 46 16 The Rise of Craft Beer in China Off the Tourist Trail: Perfect Family Days Out Cover Story 20 Special Days 48 Tianjin Open 2015: Tale of the Winners Special Days in November 2015 Restaurant -

大闸蟹chinese Mitten Crab

Advanced - 大闸蟹 Chinese Mitten Crab(E2980) A: 入秋了你怎么还在喝啤酒啊? rù qiū le nǐ zěnme háizài hē píjiǔ ā? It's already Autumn, why are you still drinking beer? B: 嘿,瞧你说的,啤酒配炸鸡不是妥妥的极致享受吗? hēi, qiáo nǐ shuō de, píjiǔ pèi zhájī bùshì tuǒtuǒde jízhì xiǎngshòu ma? Hey, what are you saying. Isn't beer and fried chicken just the perfect combination? A: 不是我打击你啊,这你就太任性了,吃喝我们也得讲究个品味,“应景” ,“应景”你听说过过吗? bùshì wǒ dǎjī nǐ ā, zhè nǐ jiù tài rènxìng le, chīhē wǒmen yě děi jiǎngjiu gè pǐnwèi,“ yìngjǐng”,“ yìngjǐng” nǐ tīngshuō guo guò ma? I'm not attacking you. You're so headstrong. With food it's necessary to pay special attention to a connection to the local environment and the season. Have you heard of this kind of idea? B: 吃个东西还这么复杂。你倒是给说道说道,这吃喝要怎么讲究“应景”。 chī gè dōngxi hái zhème fùzá。 nǐ dào shì gěi shuōdào shuōdào, zhè chīhē yào zěnme jiǎngjiu“ yìngjǐng”。 Is eating food so complicated? So tell me, how do you pay special attention to the local environment and season in what you eat and drink. A: 先不说炸鸡啤酒营养价值到底有多高,就说什么时候吃这组合“应景”吧 ,那必须得是冬天下初雪的时候啊,《来自星星的你》看了吗?那可是 教科书级别的。 xiān bù shuō zhájī píjiǔ yíngyǎng jiàzhí dàodǐ yǒu duō gāo, jiù shuō shénme shíhou chī zhè zǔhé“ yìngjǐng” ba, nà bìxū děi shì dōngtiān xià chūxuě de shíhou ā,《 láizì xīngxing de nǐ》 kàn le ma? nà kě shì jiàokēshū jíbié de。 First let's not go into how nutritional fried chicken and beer is, but rather when this combo is most appropriate to eat. That is as the first snow of winter falls. -

Rethinking Indigenous People's Drinking Practices in Taiwan

Durham E-Theses Passage to Rights: Rethinking Indigenous People's Drinking Practices in Taiwan WU, YI-CHENG How to cite: WU, YI-CHENG (2021) Passage to Rights: Rethinking Indigenous People's Drinking Practices in Taiwan , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13958/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Passage to Rights: Rethinking Indigenous People’s Drinking Practices in Taiwan Yi-Cheng Wu Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Social Sciences and Health Department of Anthropology Durham University Abstract This thesis aims to explicate the meaning of indigenous people’s drinking practices and their relation to indigenous people’s contemporary living situations in settler-colonial Taiwan. ‘Problematic’ alcohol use has been co-opted into the diagnostic categories of mental disorders; meanwhile, the perception that indigenous people have a high prevalence of drinking nowadays means that government agencies continue to make efforts to reduce such ‘problems’.