Volume 47, Nos. 3–4 (2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July-August 2012

The Maronite Voice A Publication of the Maronite Eparchies in the USA Volume VIII Issue No. VII July - August 2012 Where In The World Would You Find the Freedom That We Have In This United States of America? Dear Friends: s you know, both myself and Bishop Gregory were in Lebanon Afor approximately three weeks in June to attend the Annual Maronite Bishops’ Synod and various meetings. It was a great experience for both, receiving and sharing ideas with other Maronite Bishops from around the world. On my return, as the plane flew over American soil, I began to reflect on the various countries which we passed over. My heart went out to the people of Syria, Iraq and Jordan in the Middle East where there is persecution and heartache. I realized more and more, in that part of the world where Jesus began His teachings, the people endure much danger and are even losing the faith that has been instilled in them from Apostolic times. This is due to the environment in which they live. Except for Lebanon, there is no freedom, no liberty, no justice for all, as we enjoy in this great country. I begin to ask, do our people appreciate what we have in this great land? Yes, we are not perfect, but we must remind our immigrants and natural citizens alike, that despite our defects, where in the world would you find the freedom that we have in this United States of America? Let us thank God for his goodness to all of us for we are able to live in the land of the " FREE and the HOME of the BRAVE." During this time of the year as we celebrate the Fourth of July, let us thank God for all those who continue to work and sacrifice to make this the greatest country in the world. -

Holy and Glorious Pascha

Sunday, April 21, 2019 Christ is Risen! Indeed He is Risen! ا م ! م! ا، 1 2 ن 2019 Holy and Glorious Pascha Christos Anesti! ἀ ! Alithós Ἀ! " ῶ Anesti! ἀ ! Al-Mas #ḥ ا م ! !q$m Ḥaqqan م ! !q$m Christ is ¡Cristo Risen! resucitó! Indeed He ¡En verdad is Risen! resucitó! Feast of the Resurrection of our Lord, God and Saviour Jesus Christ We call the present Feast ‘Pascha’, which in Hebrew means ‘Passing Over’; for this is the day on which God from the beginning brought the world out of non-existence. On this same day he also made the people of Israel pass over the Red Sea and snatched them from the hands of Pharaoh. Again it was on this day that he came down from heaven and dwelt in the womb of the Virgin. And now he has snatched the whole of humanity from the vaults of Hades and made it pass upwards to heaven and brought it to its ancient dignity of incorruption. But when he descended into Hades he did not raise all, but as many as believed in him were chosen. He freed the souls of the Saints since time began who were forcibly held fast by Hades and made them all ascend to heaven. And so we, rejoicing exceed- ingly, celebrate the Resurrection with splendor as we image joy with which our nature has been en- riched by God’s compassionate mercy. 1 Remember in your prayers: Those who have fallen asleep before us in the hope of resurrection. All who are sick, suffering or recovering from illness, especially Noha Bagdasar and Fr. -

The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2017 Lux Occidentale: The aE stern Mission of the Pontifical Commission for Russia, Origins to 1933 Michael Anthony Guzik University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Guzik, Michael Anthony, "Lux Occidentale: The Eastern Mission of the Pontifical ommiC ssion for Russia, Origins to 1933" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1632. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1632 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2017 ABSTRACT LUX OCCIDENTALE: THE EASTERN MISSION OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR RUSSIA, ORIGINS TO 1933 by Michael A. Guzik The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2017 Under the Supervision of Professor Neal Pease Although it was first a sub-commission within the Congregation for the Eastern Churches (CEO), the Pontifical Commission for Russia (PCpR) emerged as an independent commission under the presidency of the noted Vatican Russian expert, Michel d’Herbigny, S.J. in 1925, and remained so until 1933 when it was re-integrated into CEO. -

Complete Teachers Manual

Teacher Resource Manual GRADE We Respond GOD WITH US 6PUBLICATIONS to God Catechesis is a work of the Church, a sharing in the teaching mission of the Body of Christ. Catechetical material, like iconography or liturgical chant, strives to speak of the Tradition of the Church. The individual's insights, perceptions, and experiences become significant in that they personalize this Tradition and give witness to it in our contemporary world. Accordingly, each text is the work of the Byzantine Catholic Churches in the United States which participate in ECDD, the catechetical arm of the bishops of Eastern Catholic Associates. We Respond to God is the work of Rev Fred Saato, a priest of the Melkite Greek Catholic Eparchy of Newton and Barbara Frazicr, M.S in Ed. with the help of Marie Yaroshak Nester, M.Ed, in English, B.S. in Secondary Education. The work was reviewed and approved by all the hierarchs of the participating eparchies, their directors of religious education, catechetical stalls, and a review board drawn from the clergy and laity of these eparchies. Therefore, it represents the common faith and vision of their communities. This project is being funded in part by the USCCB Committee on Home Missions, the Greek Catholic Union, the Koch Foundation, the John Victor Machuga Foundation, and the Providence Association for the Ukrainian Catholics in the United States. No part of this book, except the handouts, may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from GOD WITH US PUBLICATIONS [email protected] Printed in the U.S.A. -

10-20-2019 Bulletin

Sunday, October 20, 2019 Christ is among us! He is and always will be! ا ! آ ون! ا، 0 2 اول 9 20 Sixth Sunday after Holy Cross Saint of the Day Commemoration of the holy Megalomartyr Artemius A venerable Duke of Alexandria and a Patrician, Saint Artemius was held in great esteem by Constantinople. Under Julius the Apostate, this Blessed One spontaneously presented himself at the conflict in Antioch where the Emperor was persecuting Christians. After sev- eral tortures, he died by the sword. The Maronites venerate him under the name of Saint Shallita. 1 Remember in your prayers: Those who have fallen asleep before us in the hope of resur- rection. All who are sick, suffering or recovering from illness, especially Fr. Saba Shofany and Lucio Moles. Know someone in need of a prayer? Please notify Fr. Rezkallah by Wednesday to ensure they are included in the following Sunday’s special intentions. Reach Fr. Rezkallah online by visiting www.stjacobmelkite.org/prayer-request or by telephone at 858-987-2864. Tickets on sale now! Buy your tickets now for St. Jacob’s 29th Anniversary Party on Satur- day, November 9, 2019 featuring star singers Anwar El Amir and Sami Shamsi along with DJ Senar. Visit www.stjacobmelkite.org/29a for more information and a link to the reservations page. Also, see attached flyer. Do you have your prayer rope? Prayer ropes will be for sale in the social hall for a limited time. Various lengths and colors are available but they are in short supply. Don’t forget to get yours while you can! Liturgy of St. -

The Ordination of a Married Man Into the Priesthood of the Melkite

United States The ordination of a married man into the priesthood of the Melkite Church in the United States has triggered some far-ranging discussions of Eastern traditions and ecumenical prospects. By WILLIAM BOLE t was Christmas eve. Bishop John Elya, spiritual leader of the Melkite Catholics in the United States, and a night owl, had just returned to Ihis residence in Newton, Massachusetts, after celebrating midnight Mass. Instead of turning in, the prelate turned on his computer and logged onto the Internet. "To all my friends in Cyber- space, those who wrote to me recently (as recently as tonight) and those who wrote to me in the past. Grace and peace be unto you from God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ whose Birthday we celebrate," announced Bishop Elya, a Syrian-born cleric with silver hair and a goatee. Typing out his greetings, and his wish that the Internet might offer a new tool of Melkite evangelization, the bish- op mentioned one other thing in the form of a postscript: The good news of the week is the ordination of Protodeacon Andre St. Germain to holy priesthood by the laying of my humble hand, on Father Andre St. Germain (with beard) acting in his role as a deacon several Saturday, December 21, at St. Basil years ago. Seminary, Methuen, Massachusetts. arrived in print media-that the bish- their own ways of worship, their own Father Andre St. Germain has com- op's humble hand had ordained a mar- forms of ecclesiastical governance. They pleted all the philosophical and theo- ried man to the Catholic priesthood. -

IN This ISSUE in This ISSUE

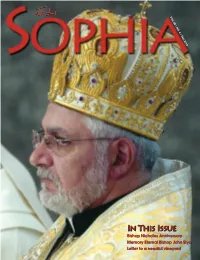

VOL. 49 | NO. 4 | FALL 2019 In This Issue Bishop Nicholas Anniversary Memory Eternal Bishop John Elya Letter to a needful vineyard CONTENTS ophia SThe Journal of the Eparchy of Newton 3 50 Years in the Service of Our Lord for Melkite Catholics in the United States www.melkite.org 7 Memory Eternal Elya, Youssef and Hull Published quarterly by the Eparchy of Newton. ISSN 0194-7958. 10 Letters to the Editor Made possible in part by the Catholic Home Mission Committee, a bequest by the Rev. Allen Maloof and generous supporters of the annual Bishop’s Appeal. 11 SOPHIA - an award winning magazine MEMBER CATHOLIC PRESS ASSOCIATION 12 Holy Land Churches are more than a pilgrimage PUBLISHER Most Rev. Nicholas J. Samra, Eparchial Bishop 14 Campaign to bring food, medicine to Syria EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Archimandrite James Babcock 15 Annual Synod of Melkite Catholic Bishops COPY EDITOR 16 Eden to Eden: A 70-year retreat Jim Trageser 18 Letter to a Needful Vineyard DESIGN AND LAYOUT Doreen Tahmoosh-Pierson 20 Why I take my kids to church SOPHIA ADVISORY BOARD Archimandrite Fouad Sayegh 21 Orientale Lumen Conference Archimandrite Michael Skrocki Fr Thomas Steinmetz | Fr Hezekias Carnazzo 22 Why I Decided to become Eastern Catholic Cary Rosenzweig 23 Pope Francis gives Orthodox patriarch relics SUBSCRIPTIONS/DISTRIBUTION Please send subscription changes to your parish office. If you are not registered 24 Pope Francis Beatifies7 Romanian martyrs in a parish please send changes to: Eparchy of Newton 26 The Power of the Cross 3 VFW Pky, West Roxbury, MA 02132 27 Melkite Catholic young adults find hope The Publisher waives all copyright to this issue. -

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum Collection, 1945-1992. Series E: General Alphabetical Files. 1960-1992 Box 79, Folder 2, Banki, Judith, 1988. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 (513) 221-1875 phone, (513) 221-7812 fax americanjewisharchives.org ANTI-ISRAEL INFLUENCE 1N AMERICAN CHURCHES A BACKGROUND REPORT - BY JUDITH HERSHCOPF BANK! Interreligious Affairs Department THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE Institute of Human Relations 165 East 56 Street, New York, N. Y. 10022 .. .. :" . · TABLE ·of . CONTENTS ... PREFACE: . Sources of Anti-Israel Sentimert · } The Arab Hi . ssio~ary ·a·nd · Relief Establ ish.ments 2 .·.. · · Lib.eratfon~st Ideol~gy · · .. .: 4 . · : . Ar~b ' Chur:c~es 5 ... Orthodox Churches 5 ·- · Eastern Rite ·Cathol.iC Churches·. 8 . ·~ " Organiiational Ties .. 11 ·At the Natio~al Council of Churches J 2· .. Other .Organizations l 3 ' Canel u.s ion 15 . •; -----· - ·------ · ·-·- ·-·-- 1.. PREFACE TMs background report is, we believe, the first to,·survey systematically the sources of anti-Israel influence within American Christian churches. What constitutes anti-Israel sentiment has been carefully delineated: the use of double standards - .harsher judgments and stricter demands made on lsr~el than· on her Arab antagonists - biased or loaded renderings of history; and sometimes, resort to theological arguments ·hostile to Judaism. · Among the recent factors which have affected negative attitudes toward . Israel is the rapid increase in immigration into the United States of Arab Christians and Moslems, resulting in a growth of population from some 250,000 to an estimated two million in the last fifteen years; coupled with recent ef forts to bolster a ~rowing pan-Arabism. ·Surely, Americ~ns of Arab heritage have the same ri9hts extende~ to all religious and ethnic groups PY American pluralistic democracy: to develop their distinctive values, culture and in fluence. -

Seventh Sunday After Pentecost Saints of The

Sunday, July 28, 2019 Christ is among us! He is and always will be! ا ! آ ون! ا، 28 ز 2019 Seventh Sunday after Pentecost Saints of the Day Commemoration of the holy Apostles and Deacons Prochoros, Nicanor, Timon, and Parmenas Saints Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon and Parmenas, Apostles of the Seventy were among the first deacons in the Church of Christ. In the Acts of the Holy Apostles (6:1-6) it is said that the twelve Apostles chose seven men: Stephen, Philip, Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas and Nicholas, full of the Holy Spirit and wisdom, and appointed them to serve as deacons. They are commemorated together today, although they died at various times and in various places. At first, St. Prochorus accompanied the holy Apostle Peter, who made him bishop in the city of Nicomedia. After the Dor- mition of the Most Holy Theotokos, Pro- chorus was a companion and coworker of the holy Apostle John the Theologian and was banished with him to the island of Patmos. There he wrote down the Book of Revelation concerning the final fate of the world. Upon returning to Nicomedia, St. Prochorus converted pagans to Christ in the city of Antioch, where he suffered martyrdom. 1 SUNDAY PICNIC IN CORONADO! August 11 at Coronado Tidelands Park starting with the Divine Liturgy at 10AM. Bring the whole family plus some friends. Food and beverages, includ- ing salad and dessert will be served for only $10. Additional details available on Facebook. No Liturgy At The Church On 8/11! Since the Divine Liturgy will be celebrated at our picnic event on Sunday, August 11, no liturgy will be celebrated at Holy Angels Church. -

State of the EPARCHY the STATE of the EPARCHY ADDRESS at the 50Th National Melkite Convention Boston Quincy Marriott Hotel JULY 2, 2016 Most Rev

State of the EPARCHY THE STATE OF THE EPARCHY ADDRESS at the 50th National Melkite Convention Boston Quincy Marriott Hotel JULY 2, 2016 Most Rev. Nicholas J. Samra Eparchial Bishop BY THE MOST REV. NICHOLAS J. SAMRA of Newton Eparchial Bishop of Newton efore I begin my journey through the Eparchy, per- small church built by the Melkite community. The mills died mit me to welcome my two immediate predecessors and most of the families scattered out of Woonsocket. We were who served this eparchy faithfully: Bishop Emeritus down to eight or ten people at Sunday Liturgy with no other John A. Elya and Archbishop Cyril Bustros, pres- parish life. With the move of St Basil Church from Central Bently Metropolitan of Beirut. I also welcome Bishop George Falls to Lincoln, RI, the Woonsocket remnant have now be- Gallaro, former priest of our eparchy, now Bishop of Piana come members of St Basil Church with a shrine to St Elias to for the Byzantine Italo-Greek/Albanians in Sicily. I’ll say a keep alive the memory of the founders of the mission church. few more words about him later. A word of welcome also to Holy Trinity Church in Zanesville, OH, was always Bishop Robert Rabbat of Australia, who is passing through served by the clergy of Holy Resurrection Church in Colum- Boston for a day or two. Welcome, brothers. bus, and most young people moved from Zanesville to larger This evening we will be blessed with the visit of Archbishop cities for school and work. Again, eight to ten people were Christophe Pierre, the new Apostolic Nuncio to the United present for Liturgy and now they drive to Columbus where States. -

International Community Is Key to a Frica's Problem S, Says Bishop

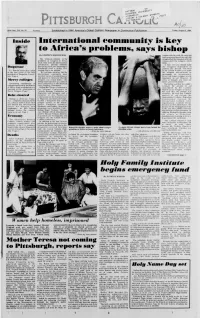

0 3 t , nrUST & COU»^- p* Av ï T O U L 140th Year, CXL No. 20 15 cents' Established in 1844: America's Oldest Catholic Newspaper in Continuous Publication Friday, August 3, 1984 In side International community is key ìJoèè to Africa’s problems, says bishop By STEPHEN KAKL1NCHAK surplus fish for cash. He said that such programs benefit not only the The "ultimate solution" to the refugees but the nationals who will problems of refugees in Africa remain after the refugees return must come from the international home. community, Bishop Anthony " I don't feel you should make D u q u e s n e Bevilacqua said after returning to the refugees dependent on Pittsburgh from a 18-day l'act- »(direct) aid," he said. "The focus Fr. Donald Nesti takes a look linding trip to six nations. of the United Nations is to make at his lour years as the 10th "W e can hope and pray, but the the refugees self-sufficient by president of Duquesne Univer international community must developing an infrastructure. sity. Page 2. use their means to establish peace Direct aid makes refugees overly and justice in Alrica so that the dependent on aid. However, in M ercy colleges relugees can return home," the areas of drought, you must use bishop told reporters at a July 31 direct aid to feed people. " Increasing enrollments at press conference at the diocesan The bishop said that he couldn't colleges operated by the Sisters office building, Downtown. estimate the amount of aid ol Mercy leads to optimism at a Bishop Bevilacqua, chairman of contributed by the Catholic meeting of the Association of the National Conference of Church to aid refugees in Africa, Mercy Colleges. -

Sixth Sunday After Pentecost Saints of The

Sunday, July 21, 2019 Christ is among us! He is and always will be! ا ! آ ون! ا، 21 ز 2019 Sixth Sunday after Pentecost Saints of the Day Commemoration of our venerable Fathers Simeon, a Fool-for-Christ's-Sake, and his companion John Saints Simeon and John were natives of Edessa, Syria. They went to Jeru- salem and withdrew to the monastery of Saint Gerasimos. Clothed in the holy monastic habit, they spent forty years in the desert in austerities and ascetical exercises. Saint John re- mained in the desert until the end of his life. On the contrary, Saint Simeon went to Emesa. There he feigned madness, which merits for him the surname of "a Fool-for-Christ's-Sake." He was only recognized after his death. Each one related a characteris- tic of his life that the others had not known about. All these accounts have served for the faithful's edification and usefulness. Born around the year 522, he died in peace around the end of the Sixth century. 1 SUNDAY PICNIC IN CORONADO! August 11 at Coronado Tidelands Park starting with the Divine Liturgy. Bring the whole family plus some friends. Food and beverages will be served for a small donation. Additional details are forthcoming but please mark your calendars! No Liturgy At The Church On 8/11! Since the Divine Liturgy will be celebrated at our picnic event on Sunday, August 11, no liturgy will be celebrated at Holy Angels Church. Please spread the word. Memory Eternal: His Grace, Bishop Emeritus +John Adel Elya fell asleep in the Lord on July 19, 2019.