Engaging the Savage Imagina[Ion: an Actors Search for the Heart of Bottom in I I a Midsummer Night's Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressive and Varied

INDIECAN ENTERTAINMENT presents MOON POINT A Film by Sean Cisterna (82 min, Canada, 2011) DISTRIBUTION Avi Federgreen [email protected] 416‐898‐3456 High res stills may be downloaded from: http://www.moonpointmovie.com/media.html ONE LINE An ambitionless 24‐year old travels hundreds of miles in an electric wheelchair to track down his grade‐school crush. SHORT SYNOPSIS MOON POINT is the story of Darryl Strozka (Nick McKinlay), a socially awkward and ambitionless 23‐year old who seems destined to live forever with his mother. As his cocky cousin Lars’ wedding approaches, Darryl decides that the best way to prove to his family that he is not quite as worthless as they think he is, is to track down his elementary school crush, now an obscure B‐movie actress shooting a horror film in Moon Point, and bring her to the wedding. Darryl enlists his best friend, known affectionately as Femur (Kyle Mac), and travels hundreds of miles in a wagon hooked onto the back of Femur’s electric wheelchair. On their journey, the boys meet Kristin (Paula Brancati), a sharp, sarcastic young woman who is running away from a relationship back home. Eager to join the boys on their adventure, she begins to realize that love can find you in unlikely places. But naturally, as tends to happen on such a quest, things don’t turn out quite as planned. Along the way, Darryl and his friends get shot at, track a banana to an AA meeting, and are the victims of theft by a karaoke competitor. -

When a Life Is in Our Hands, Your Support Matters Most Contents

Sunnybrook Fou nd ation Report to Donors 2015 When a life is in our hands, your support matters most Contents Leadership Message 2 Trauma, Emergency & 40 Critical Care Program Hurvitz Brain 12 Sciences Program Sunnybrook Rose Awards 44 Women & Babies Program 18 In tribute 45 Odette Cancer Program 20 Board of Directors 46 Schulich Heart Program 26 Governing Council 48 Research 30 Counsel 50 St. John’s Rehab Program 34 Advancement Committee 50 Veterans & Community 36 Sunnybrook Next Generation 50 Program Thank you to our donors 51 Community 38 Every day at Sunnybrook I see evidence of life-changing work, whether Holland Musculoskeletal 39 Program it’s a world-first procedure, the safe delivery of a premature baby or a groundbreaking discovery in one of our laboratories. Our team of experts is committed to inventing the future of healthWhen care, a today. young woman can This commitment means we are constantlyescape pushing the the frontiers devastation of research, developing innovative therapies and putting leading-edge technology to of stroke. the test. As a result, we are able to provide our patients with new options for diagnosis and treatment that were previously impossible – options that are minimally invasive, more precise, cause fewerWhen side-effects a baby and born save more months lives. All of this is possible because of our strongtoo partnership early with can Sunnybrook defy Foundation and our community of donors.the It is yourodds generosity and thatsurvive. supports our hard work and accomplishments, and it is your belief in us that drives us forward. The Foundation’s annual report celebrates philanthropy and volunteer leadership, vital engines pushingWhen us to achievea cancer our strategic patient imperatives. -

A Murder of Crows: Second Book of the Junction Chronicles Online

ELGiR [Read ebook] A Murder of Crows: Second Book of the Junction Chronicles Online [ELGiR.ebook] A Murder of Crows: Second Book of the Junction Chronicles Pdf Free David Rotenberg DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4912184 in Books 2013-04-16 2013-04-16Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x .90 x 6.00l, .0 #File Name: 1476746885336 pages | File size: 48.Mb David Rotenberg : A Murder of Crows: Second Book of the Junction Chronicles before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised A Murder of Crows: Second Book of the Junction Chronicles: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Reading through The Junction ChroniclesBy PamelaDavid Rotenberg's second volume in The Junction Chronicles maintains the suspense set up in the first. Decker Roberts' ability to know if someone is telling the truth is still an uncomfortable and dangerous gift that makes him vulnerable to the plotting and manipulation of those in power. Allied to the very human sadness over his relationship with his son, Decker's personal and public dilemma once more become intertwined. Still at times Rotenberg allows the narrator to voice significant judgments, rather than have the characters and the reader discern these. It happens rarely, however, and the complex viewpoints in the novel are mostly revealed through the voice of a character. Key characters, Yslan Hicks for example, are becoming more complex and it is less certain that the roles they play are straightforward. Rotenberg maintains, along with the everyday political and social dimension of his fictional world, a more metaphysical level. -

MAKING the SCENE: Yorkville and Hip Toronto, 1960-1970 by Stuart

MAKING THE SCENE: Yorkville and Hip Toronto, 1960-1970 by Stuart Robert Henderson A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada October, 2007 Copyright © Stuart Robert Henderson, 2007 Abstract For a short period during the 1960s Toronto’s Yorkville district was found at the centre of Canada’s youthful bohemian scene. Students, artists, hippies, greasers, bikers, and “weekenders” congregated in and around the district, enjoying the live music and theatre in its many coffee houses, its low-rent housing in overcrowded Victorian walk- ups, and its perceived saturation with anti-establishmentarian energy. For a period of roughly ten years, Yorkville served as a crossroads for Torontonian (and even English Canadian) youth, as a venue for experimentation with alternative lifestyles and beliefs, and an apparent refuge from the dominant culture and the stifling expectations it had placed upon them. Indeed, by 1964 every young Torontonian (and many young Canadians) likely knew that social rebellion and Yorkville went together as fingers interlaced. Making the Scene unpacks the complicated history of this fraught community, examining the various meanings represented by this alternative scene in an anxious 1960s. Throughout, this dissertation emphasizes the relationship between power, authenticity and identity on the figurative stage for identity performance that was Yorkville. ii Acknowledgements Making the Scene is successful by large measure as a result of the collaborative efforts of my supervisors Karen Dubinsky and Ian McKay, whose respective guidance and collective wisdom has saved me from myself on more than one occasion. -

Press Kit Season 1 and 2

www.mohawkgirls.com PREMIERING ON OMNI SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 23 AND ON APTN TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 25. TAGLINE Welcome to our world. (Just watch your back.) LOGLINE Mohawk Girls is a half hour dramatic comedy about four young women figuring out how to be Mohawk in the21st century. SYNOPSIS - SHORT What does it mean to be a modern day Mohawk woman? Mohawk Girls is a half hour dramatic comedy about four young women trying to figure out the answer. But with their parents, friends, community, and even their garbage man having an opinion, it’s an impossible task. SYNOPSIS - LONG Mohawk Girls centers around four twenty-something Mohawk women trying to find their place in the world, and of course, trying to find love. But in a small world where you or your friends have dated everyone on the rez, or the hot new guy turns out to be your cousin, it ain’t that simple. Torn between family pressure, tradition, obligation and the intoxicating freedom of the “outside world,” this fabulous foursome is on a mission to find happiness… and to find themselves. Bailey, 29, wants to be the “perfect” Mohawk. Everyone in her life seems to have a strong idea of what that means and she tries to live by their rules and meet their expectations. Unfortunately her heart starts taking her in very different directions and she finds herself having to constantly choose between her own happiness and everyone else’s. Caitlin, 27, is a full-figured sex-bomb who flaunts what god gave her and flirts with all the boys, even when she shouldn’t. -

GRÀCIA Our Neighbourhood

FRANKFURT 2014 8-12TH OCTOBER GRÀCIA our neighbourhood FRANKFURT BOOKFAIR October 2014 Featuring New Titles from Sandra Bruna’s agency represented lists ● ADULT pg. 2 ● CHILDREN / YA pg. 61 1 ADULT TITLES FICTION pg. 8 NON FICTION pg. 32 SHORT STORIES pg. 46 POETRY pg. 48 2 A - Z Foreign agencies and publishers represented ►ALLIED AUTHORS AGENCY Spain, Portugal, Latin America & Brazil / www.alliedauthorsagency.be A DAY WITH MR. JULES, Diane Broeckhoven 8 ELVIS A. PRESLEY. MUSIC, MAN, MYTH, Marc Hendrickx 35 HARMATTAN, Gavin Weston 13 THE JUGGLER, Sebastian Beaumont 26 THE PECULIAR LIFE OF A LONELY POSTMAN (aka THE POSTMAN ROUND), Denis Thériault 27 THIRTEEN, Sebastian Beaumont 30 ►AMAZON Spain, Portugal, Latin America & Brazil / www.amazon.com See page 49 ►COACH HOUSE BOOKS Spain, Portugal, Latin America & Brazil / www.chbooks.com ALL MY FRIENDS ARE SUPERHEROES, Andrew Kaufman 8 AMPHIBIAN, Carla Gunn 9 IN LOVE WITH ART, Jeet Heer 37 CURATIONISM, David Balzer 34 PASTORAL, André Alexis 20 ►COFFEE HOUSE PRESS Spain, Portugal, Latin America & Brazil / www.coffeehousepress.org BRIGHTFELLOW, Rikki Durcornet 9 GENOA. A TELLING OF WONDERS, Paul Metcalf 36 HOW A MOTHER WEANED HER GIRL FROM FAIRY TALES, Kate Bernheimer 47 IT WILL END WITH US, Sam Savage 15 LEAVING THE ATOCHA STATION, Ben Lerner 16 MR. AND MRS. DOCTOR, Julie Iromuanya 18 THE ARTIST’S LIBRARY, E. Batykefer and L. Damon-Moore 41 THE BALTIMORE ATROCITIES, John Dermot Woods 23 THE BLUE GIRL Laurie Foos 24 ►ÉDITIONS HURTUBISE Spain, Portugal, Latin America & Brazil / www.editionshurtubise.com IL PLEUVAIT DES OISEAUX, Jocelyne Saucier 15 THE LITTLE GIRL AND THE OLD MAN, Marie-Renée Lavoie 26 ►FINCH PUBLISHING Spain, Portugal, Latin America & Brazil / www.finch.com.au 20 TIPS FOR PARENTS, K. -

Director/Writer/Acting Teacher

DAVID ROTENBERG - Director/Writer/Acting Teacher NOVELS: The Shanghai Murders - St. Martin’s Press, NYC, 1998 – Hardcover, McArthur and Company, Toronto - Mass Market Paperback, 2002 “This awesome first novel ... an excellent police procedural ... wonderfully nefarious” –Library Journal “Irresistibly exotic” –Publisher’s Weekly “An extraordinarily accomplished mystery” –Booklist. The Lake Ching Murders - St. Martin’s Press, NYC, 2002 – Hardcover, McArthur and Company, Toronto, 2001 - Trade Paperback “Peeks into the subtle intricacies of Chinese society while producing a clever murder mystery” – National Post “Can’t Go Wrong with Fong” – The Toronto Sun The Hua Shan Hospital Murders - McArthur and Company, Toronto, 2003 “A fascinating journey into a remarkable culture” –Ottawa Citizen “Wit, intelligence and imagination have become standard in the works of David Rotenberg”–The Halifax Chronicle-Herald “This is the third book in this wonderful series.” –Margaret Cannon for the Globe and Mail. SHORT LISTED AS THE BEST CRIME NOVEL OF 2003 The Hamlet Murders - McArthur and Company, 2004 “Rotenberg has a real talent for characterization and place, taking readers right into the urban heart of Shanghai, with its 18 million people and conflicts between tradition and modernization.” –Margaret Cannon for the Globe and Mail. STAGE DIRECTING - highlights: • Two Broadway shows - The News at the Helen Hayes Theatre (Director and Co- book Writer), The 1940's Radio Hour at the St. James Theatre • 36 Regional Theatre Shows at such theatres as The Williamstown Theatre Festival, The Pittsburgh Public Theatre, The Indiana Repertory Theatre, Playmaker Repertory Theatre and The Annenburg Centre 1 • Artistic Director of North Carolina’s Regional Theatre - Playmaker Repertory Theatre for three years. -

People and Pass Ions

PEOPLE AND PASSIONS 6JGYTKVKPIUQH&CXKF4QVGPDGTI by Jurgen Gothe It’s amazing what you can come up with after spending 10 weeks in a foreign culture, unable to speak the language, keeping your eyes wide open and soaking up sights and sounds. If you have a ready imagina- tion, that is. Which David Rotenberg surely has. TALENT Theatre is his domain, primarily as a director, although in recent YI years he has taken to writing, exhibiting a natural talent and skill set F that makes his work read like that of a decades-long veteran of the craft. Rotenberg, Torontonian, good academic credentials: degrees from the University of Toronto, an MFA in directing from Yale School of Drama. Then young enough to heed the timeless call and head out west. In British Columbia, he set up the acting program at Simon Fraser University and taught there. Then he travelled south; 10 years in New York, with lots of freelance directing, plenty of regional theatre, and two Broadway shows. In 1987, he got a call from York University to head up the graduate acting program there. Standard stuff so far, not all that amazing. Yet. He pretty much expected to resume his directing career in his hometown, something he could probably have done in his sleep, but he got a rude awakening. “I was effectively shunned,” he recalls. The powers that be (or at least, were) basically told him to forget directing in Canada. Jump to 2003, when he started Canada’s most successful actor train- ing program, the Professional Actors Lab, which he still runs, with nearly 200 actors per term. -

Selected Canadian Mysteries, by Author

Selected Canadian Mysteries, by Author As recommended by Kathleen Fraser for Learning Unlimited, January 2019 Cathy Ace: Welsh-born Canadian author of the Cate Morgan and WISE Women cozies, fun series set in Wales. Grant Allen: Born in Kingston, Ontario, author of An African Millionaire: Episodes in the Life of the Illustrious Colonel Clay (1897). Colonel Clay was a scoundrel and adventurer – and Allen almost equally scandalous. Thought the first Canadian to seriously attempt crime writing professionally. Arthur Conan Doyle completed his last novel. Lou Allin: The Belle Palmer series in Northern Ontario; Holly Martin (RCMP) series on Vancouver Island. Toni Anderson: “Smart, sexy thrillers with happily ever after.” Haven’t read this, but it was recommended to me. Hubert Aquin: In Prochaine Episode / Next Episode (1965), the narrator, like Aquin himself, turns his adventures into a spy thriller while awaiting trial for an unnamed crime, locked up in the psychiatric ward of a Montreal prison. Kelley Armstrong: The Rockton thrillers, starting with City of the Lost, are probably Armstrong’s most conventional novels, in that they contain no demons or werewolves, but they are by no means ordinary. Rockton is a tiny town hidden in the Yukon, where people like ex-cop Casey Duncan go to escape their pasts. Enthralling. Carolyn Arnold: Author of four very different series, including Brandon Fisher FBI, set in the US. Catherine Astolfo: Series featuring Emily Taylor, small-town Ontario school principal. Margaret Atwood: Yes, most of her novels have a mystery at the core. Not that she always resolves the mystery, however. Take Alias Grace, for example. -

2012 Annual Catalogue MYSTERY SUSPENSE/THRILLER NONFICTION YOUNG ADULT SHORT STORIES & ANTHOLOGIES

COOL CANADIAN CRIME 2012 Annual Catalogue MYSTERY SUSPENSE/THRILLER NONFICTION YOUNG ADULT SHORT STORIES & ANTHOLOGIES 2012 Member Books By Release Date January Anthony Bidulka, Dos Equis, Insomniac Press James T. Barrett, Deferred Prejudice, JT Barrett Gail Bowen, Kaleidoscope, Random House Colleen Cross, Exit Strategy, Slice Publishing Alison Bruce, Deadly Legacy, Imajin Books Stanley Evans, Seaweed in the Mythworld, Ekstasis Liz Bugg, Oranges and Lemons, Insomniac Press Editions Erika Chase, A Killer Read, Berkley Prime Crime Julia Madeleine, The Truth About Scarlet Rose, Vicki Delany, A Winter Kill, Orca/Rapid Reads Malefic Vicki Delany, Burden of Memory, Poisoned Pen Press Rick Mofina, The Burning Edge, MIRA Vicki Delany, Gold Mountain, Dundurn Rene Natan, The Bricklayer, Createspace Vicki Delany, Scare the Light Away, Poisoned Pen Howard Shrier, Boston Cream, Random House/Vintage Press Elizabeth Elwood, The Agatha February Brian Lloyd French, Mojito!, Realciprocity Peggy Blair, The Beggar’s Opera, Penguin Canada Principle and Other Mystery Stories, iUniverse Hilary Davidson, The Next One to Fall, Tom Doherty David. A. Gibb, Camouflaged Killer, Berkley Books Assoc. A.R. Grobbo, Suitable Fate, Double Dragon Publishing R.J. Harlick, A Green Place for Dying , Dundurn Dave Hugelschaffer, Whiskey Creek, Cormorant Books David Rotenberg, The Placebo Effect, Simon & Julia Madeleine, Stick A Needle In My Eye, Malefic Schuster Julia Madeleine, The Refrigerator Girls, Malefic Phyllis Smallman, Champagne For Buzzards, Simone St. James, The Haunting of Maddy Clare, NAL McArthur Co May March Janet Bolin, Threaded For Trouble, Berkley Prime Cathy Ace, The Corpse with the Silver Tongue, Crime TouchWood Robert Landori, Mayhem on the Danube, AuthorHouse Debra Purdy Kong, Deadly Accusations, TouchWood D.J. -

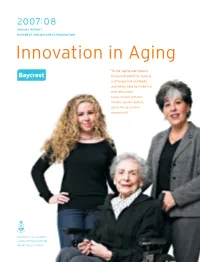

Baycrest AR 2007-08 Final.3.Indd

2007| 08 ANNUAL REPORT BAYCREST AND BAYCREST FOUNDATION Innovation in Aging “To me, aging well means being independent, having a strong mind and body, and being able to make my own decisions.” Lesley Kroach with her mother, Apotex resident Sylvia Emsig, and her daughter, Ali. Baycrest is an academic centre affi liated with the University of Toronto. In the 90 years of its existence, inspired by the values of Judaism, Baycrest has earned and sustained a national and international reputation for excellence in geriatric care, scientifi c discovery—particularly in the area of brain health—and the education of new generations of health-care providers. It has done so with the support of world-renowned clinicians and researchers, skilled and committed staff, many thousands of dedicated volunteers, and remarkably generous donors. For information about Baycrest’s programs and services, please visit us online at www.baycrest.org MISSION The mission of Baycrest is to enrich the quality of life of the elderly guided always by the principles of Judaism. VISION Baycrest will transform the way people age and advance care and quality of life to a new level, through the power of research and education, and with a focus on brain functioning and mental health. “To age well, it is important to have a positive attitude— to see the glass half full. And a sense of humour is important, too—to be able to laugh even in hard situations— and to continue to do things that you enjoy.” Elva Barrowman, pictured here with daughter Elayne Clarke, lives independently and in good health at age 93. -

An Awkward Sexual Adventure

TRIBECA FILM in partnership with AMERICAN EXPRESS presents a julijette inc. & Banana-Moon Sky production AN AWKWARD SEXUAL ADVENTURE Directed by Sean Garrity Written by Jonas Chernick Available on VOD March 19, 2013 Run Time: 103 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Press Materials can be downloaded at: http://www.tribecafilm.com/festival/media/tribeca-film-press/ Distributor: Tribeca Film 375 Greenwich Street New York, NY 10011 TRIBECA FILM: ID PR: Jen Holiner 212-941-2038 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FESTIVALS & AWARDS Toronto International Film Festival – September 2012 – World Premiere Named one of TIFF’s Top Ten Films of 2012. Calgary International Film Festival – September 2012 Winner of the People’s Choice Award for Best Narrative Film. Mar del Plata International Film Festival – November 2012 – Mar del Plata, Argentina – In Competition. Whistler Film Festival – November 2012 In Competition for the Borsos Award for Best Canadian Feature Film Winner of the Audience Award for Best Feature Film. Santa Barbara International Film Festival – January 2013 – US Premiere Atlanta Jewish Film Festival – February 2013 – Atlanta, Georgia ACTRA Awards – February 2013 Nominated for Outstanding Male Performance – Jonas Chernick Kingston Canadian Film Festival – March 2013 – Kingston, Ontario, Canada Golden Horse Fantastic Film Festival – March 2013 – Taipei, Taiwan – Asia Premiere FEATURING Jonas Chernick Emily Hampshire Sarah Manninen Vik Sahay 2 SYNOPSIS Dumped by his girlfriend over his sub-par sex skills, uptight accountant Jordan (Jonas Chernick) goes to visit his lothario friend Dandak (Vik Sahay), hoping to learn some tricks to improve his game. Instead, he ends up finding a “sex Yoda” in Julia (Emily Hampshire, COSMOPOLIS), a worldly stripper with a mountain of debt; in exchange for teaching her money management, she agrees to introduce Jordan to a brave new world of massage parlors, cross-dressing, and S&M.