Asian Regional Powers: Junta's Lifelines but Not Change Agents?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Additional Agenda Item, Report of the Officers of the Governing Bodypdf

International Labour Conference Provisional Record 2-2 101st Session, Geneva, May–June 2012 Additional agenda item Report of the Officers of the Governing Body 1. At its 313th Session (March 2012), the Governing Body requested its Officers to undertake a mission (the “Mission”) to Myanmar and to report to the International Labour Conference at its 101st Session (2012) on all relevant issues, with a view to assisting the Conference’s consideration of a review of the measures previously adopted by the Conference 1 to secure compliance by Myanmar with the recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry that had been established to examine the observance by Myanmar of its obligation in respect of the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29). 2. The Mission, composed of Mr Greg Vines, Chairperson of the Governing Body, Mr Luc Cortebeeck, Worker Vice-Chairperson of the Governing Body, and Mr Brent Wilton, Secretary of the Employers’ group of the Governing Body, as the personal representative of Mr Daniel Funes de Rioja, the Employer Vice-Chairperson of the Governing Body, visited Myanmar from 1 to 5 May 2012. The Mission met with authorities at the highest level, including: the President of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; the Speaker of the Parliament’s lower house; the Minister of Labour; the Minister of Foreign Affairs; the Attorney-General; other representatives of the Government; and the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services. It was also able to meet and discuss with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, President of the National League for Democracy (NLD); representatives of other opposition political parties; the National Human Rights Commission; labour activists; the leaders of newly registered workers’ organizations; and employers’ representatives from the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI) and recently registered employers’ organizations. -

Sample Chapter

lex rieffel 1 The Moment Change is in the air, although it may reflect hope more than reality. The political landscape of Myanmar has been all but frozen since 1990, when the nationwide election was won by the National League for Democ- racy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The country’s military regime, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), lost no time in repudi- ating the election results and brutally repressing all forms of political dissent. Internally, the next twenty years were marked by a carefully managed par- tial liberalization of the economy, a windfall of foreign exchange from natu- ral gas exports to Thailand, ceasefire agreements with more than a dozen armed ethnic minorities scattered along the country’s borders with Thailand, China, and India, and one of the world’s longest constitutional conventions. Externally, these twenty years saw Myanmar’s membership in the Associa- tion of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), several forms of engagement by its ASEAN partners and other Asian neighbors designed to bring about an end to the internal conflict and put the economy on a high-growth path, escalating sanctions by the United States and Europe to protest the military regime’s well-documented human rights abuses and repressive governance, and the rise of China as a global power. At the beginning of 2008, the landscape began to thaw when Myanmar’s ruling generals, now calling themselves the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), announced a referendum to be held in May on a new con- stitution, with elections to follow in 2010. -

Burma Road to Poverty: a Socio-Political Analysis

THE BURMA ROAD TO POVERTY: A SOCIO-POLITICAL ANALYSIS' MYA MAUNG The recent political upheavals and emergence of what I term the "killing field" in the Socialist Republic of Burma under the military dictatorship of Ne Win and his successors received feverish international attention for the brief period of July through September 1988. Most accounts of these events tended to be journalistic and failed to explain their fundamental roots. This article analyzes and explains these phenomena in terms of two basic perspec- tives: a historical analysis of how the states of political and economic devel- opment are closely interrelated, and a socio-political analysis of the impact of the Burmese Way to Socialism 2, adopted and enforced by the military regime, on the structure and functions of Burmese society. Two main hypotheses of this study are: (1) a simple transfer of ownership of resources from the private to the public sector in the name of equity and justice for all by the military autarchy does not and cannot create efficiency or elevate technology to achieve the utopian dream of economic autarky and (2) the Burmese Way to Socialism, as a policy of social change, has not produced significant and fundamental changes in the social structure, culture, and personality of traditional Burmese society to bring about modernization. In fact, the first hypothesis can be confirmed in light of the vicious circle of direct controls-evasions-controls whereby military mismanagement transformed Burma from "the Rice Bowl of Asia," into the present "Rice Hole of Asia." 3 The second hypothesis is more complex and difficult to verify, yet enough evidence suggests that the tradi- tional authoritarian personalities of the military elite and their actions have reinforced traditional barriers to economic growth. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Burmese Students Seek Arms

ERG- 20 NOT FOR PUBLICATION WITHOUT WRITER'S CONSENT INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS Bangkok October, 1988 "An Idea Plus a Bayonet'" Burmese Students Seek Arms My second attempt to enter Burma, this time through the back door on the southern Thai border, was halted by a sudden high fever.. Thus, this report on the Burmese student movement comes to you after a quinine-induced haze. In the aftermath of the bloody September 18 coup by Gen. Saw Maung, well over 3,000 students have fled Rangoon and other cities for the Thai border, seeking arms and refuge. Student leaders on the Thai-Burmese border say that peaceful protests alone, especially the type advocated by the elderly opposition leaders in Rangoon, are doomed to fail.. One soft-spoken student said of the opposition leaders in Rangoon, "They have ideas but no guns. Revolution equals an idea plus a bayonet." Maung Maung Thein, a stocky Rangoon University student, led 74 other students out of Rangoon on September 7, eleven days before the coup. Convinced that armed struggle was the only way to overthrow the regime, they traveled over 700 miles down the Burmese coast by passenger bus, boat, and on foot. Sometimes they moved at night to avoid Army checkpoints. But this was during the heady days before the coup when one opposi- tion leader, Aung Gyi, predicted that the government would fall in a matter of weeks. Crowds of people welcomed the students, presenting them with rice and curry. As one student described it, "They were clapping. Some of the women called us their sons. -

Military Competition Between Allied Forces and Japan: a Case Study on Mandalay Campaign in Myanmar (1942-1945)

1,886 International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 9, Issue 2, February-2018 ISSN 2229-5518 Military Competition between Allied Forces and Japan: A Case Study on Mandalay Campaign in Myanmar (1942-1945) Thin Thin Aye* Abstract: This paper discusses the military competition between Allied Forces and Japan in Mandalay, and the situation of Mandalay during the Second World War. Mandalay is located in upper Myanmar and the center of the communications between lower and upper Myanmar. The British occupied Mandalay in the end of 1885. Since that time the princes and his followers attacked the British. In 1930s, Myanmar nationalists joined with the Japanese fought for British. In 1942, due to Myanmar fell under Japan, Allied forces left for Myanmar. In 1945, Allied Forces tried to reoccupy Myanmar. On 17 May 1945, after the fall of Mandalay, the Japanese retreated from Myanmar. The campaign between the Allied Forces and Japan in Myanmar was ended. In this paper examines military competition of Allied Forces and Japan in Mandalay, and the situation of Mandalay during the Second World War. Keywords: Japanese Forces, Allied Forces, Myanmar Nationalist Movement, Mandalay —————————— —————————— Introduction To study the Myanmar history, the British occupied his paper discusses the military competition between Myanmar in 1885, the Japanese occupied in 1942, the British Allied Forces and Japan in Mandalay, and the situation reoccupied in 1945. In these wars were brought about military Tof Mandalay during the Second World War. Mandalay, competitions between Allied forces and Japanese forces. It can ancient royal city was founded in upper Myanmar by King be found that these military competitions were usually ended Mindon in 1853. -

From Kunming to Mandalay: the New “Burma Road”

AsieAsie VVisionsisions 2525 From Kunming to Mandalay: The New “Burma Road” Developments along the Sino-Myanmar border since 1988 Hélène Le Bail Abel Tournier March 2010 Centre Asie Ifri The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the authors alone. ISBN : 978-2-86592-675-6 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2010 IFRI IFRI-BRUXELLES 27 RUE DE LA PROCESSION RUE MARIE-THÉRÈSE, 21 75740 PARIS CEDEX 15 - FRANCE 1000 - BRUXELLES, BELGIQUE PH. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 PH. : +32 (2) 238 51 10 FAX: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 FAX: +32 (2) 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] WEBSITE: Ifri.org China Program, Centre Asie/Ifri The Ifri China Program’s objectives are: . To organize regular exchanges with Chinese elites and enhance mutual trust through the organization of 4 annual seminars in Paris or Brussels around Chinese participants. -

U.S. Restrictions on Relations with Burma

U.S. Restrictions on Relations with Burma Updated March 18, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44570 U.S. Restrictions on Relations with Burma Summary Major changes in Burma’s political situation since 2016 have raised questions among some Members of Congress concerning the appropriateness of U.S. policy toward Burma (Myanmar) in general, and the current restrictions on relations with Burma in particular. During the time Burma was under military rule (1962–2011), restrictions were placed on bilateral relations in an attempt to encourage the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, to permit the restoration of democracy. In November 2015, Burma held nationwide parliamentary elections from which Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) emerged as the party with an absolute majority in both chambers of Burma’s parliament. The new government subsequently appointed Aung San Suu Kyi to the newly created position of State Counselor, as well as Foreign Minister. While the NLD controls the parliament and the executive branch, the Tatmadaw continues to exercise significant power under provisions of Burma’s 2008 constitution, impeding potential progress towards the re-establishment of a democratically-elected civilian government in Burma. On October 7, 2016, after consultation with Aung San Suu Kyi, former President Obama revoked several executive orders pertaining to sanctions on Burma, and waived restrictions required by Section 5(b) of the Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE (Junta Anti-Democratic Efforts) Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-286), removing most of the economic restrictions on relations with Burma. On December 2, 2016, he issued Presidential Determination 2017-04, ending some restrictions on U.S. -

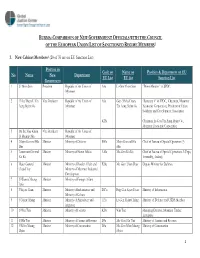

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

The Journal of Burma Studies

The Journal of Burma Studies Volume 8 2003 Featuring Articles by: Susanne Prager Megan Clymer Emma Larkin The Journal of Burma Studies President, Burma Studies Group F.K. Lehman General Editor Catherine Raymond Center for Burma Studies, Northern Illinois University Production Editor Peter Ross Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University Publications Assistants Beth Bjorneby Mishel Filisha The Journal of Burma Studies is an annual scholarly journal jointly sponsored by the Burma Studies Group (Association for Asian Studies), The Center for Burma Studies (Northern Illinois University), and Northern Illinois University’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Articles are refereed by professional peers. Send one copy of your original scholarly manuscript with an electronic file. Mail: The Editor, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115. Email: [email protected]. Subscriptions are $16 per volume delivered book rate (Airmail add $10 per volume). Members of the Burma Studies Group receive the journal as part of their $25 annual membership. Send check or money order in U.S. dollars drawn on a U.S. bank made out to "Northern Illinois University" to Center of Burma Studies, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115. Visa and Mastercard orders also accepted. Subscriptions Tel: (815) 753-0512 Fax: (815) 753-1651 E-Mail: [email protected] Back Issues: seap@niu Tel: (815) 756-1981 Fax: (815) 753-1776 E-Mail: [email protected] For abstracts of forthcoming articles, visit The Journal of Burma -

1 LEGAL EDUCATION in BURMA SINCE the 1960S: Myint Zan* I INTRODUCTION in the January 1962 Issue of International and Comp

1 LEGAL EDUCATION IN BURMA SINCE THE 1960s: Myint Zan* This longer version of the articles that appeared in The Journal of Burma Studies was submitted by the author and is presented unedited in this electronic form. I INTRODUCTION In the January 1962 issue of International and Comparative Law Quarterly the late Dr Maung Maung (31 January 1925- 2 July1994)1 wrote a short note and comment in the Comments Section of the Journal entitled ‘Lawyers and Legal Education in Burma’.2 Since then much water has passed under the bridge in the field of legal education in Burma and to the best of this author’s knowledge there has never been an update in academic legal journals or in books about the subject. This article is intended to fill this lacuna in considerable detail and also to comment on variegated aspects of legal education in Burma since the 1960s. Dr Maung Maung’s Note of 1962 is a brief survey of Burma’s legal education from the time of independence in 1948 to about March 19623: the month and the year the * BA, LLB (Rangoon), LLM (Michigan), M.Int.Law (Australian National University), Ph.D. (Girffith) SeniorLecturer, School of Law, Multimedia Univesity, Malacca, Malaysia. 1 BA (1946) (Rangoon University), BL (Rangoon) (1949), LLD (Utrecht) (1956), JSD (Yale) (1962), of Lincoln’s Inn Barrister-at-law. 2 Maung Maung, ‘Lawyers and Legal Education in Burma’ (1962) 11 International and Comparative Law Quarterly 285-290, This ‘Note’ published while Maung Maung was a visiting scholar at Yale University in the United States is reproduced with slight modifications in Maung Maung, Law and Custom in Burma and the Burmese Family (Martinus Nijhoff, 1963) 137-141. -

Annex to News Release Financial Sanctions: Burma

ANNEX TO NEWS RELEASE FINANCIAL SANCTIONS: BURMA THE BURMA (SANCTIONS) (EU EXIT) REGULATIONS 2019 (S.I. 2019/136) ADDITIONS Individuals 1. SAN, Tin Aung DOB: 16/10/1960. POB: Myanmar Nationality: Myanmar Address: Myanmar. Position: (1) Commander-in-Chief of the Burmese Navy (2) SAC Member Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref): BUR0019 (UK Statement of Reasons): On 1 February 2021 the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw), led by Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing, staged a coup in Myanmar. As part of the coup, Vice-President Swe declared a state of emergency on 1 February transferring the legislative, executive and judicial powers of the state to Min Aung Hlaing. On 2 February, the Tatmadaw established the State Administration Council (SAC), which is chaired by Hlaing, in order to run the functions of the state. General Tin Aung San was appointed to the SAC on 2 February. The Myanmar security forces have committed serious human rights violations since 1 February 2021: killing a protestor, restricting freedom of assembly and expression including through restricting internet access, arbitrary arrest and detention of opposition leaders and opponents of the coup. The SAC has adopted legislation violating the right to privacy and the right not to be subject to arbitrary detention in Myanmar. As a member of the SAC, Tin Aung San shares responsibility with its other members for the exercise of state functions since 2 February 2021, including legislation violating human rights, and for the serious human rights violations committed by the Myanmar security forces. As a member of the SAC, Gen Tin Aung San is associated with Commander in Chief General Min Aung Hlaing who is a designated person under the Burma (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 in respect of actions related to the February 2021 coup.