EDVARD MUNCH's 'ALPHA and OMEGA' Seriess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDVARD MUNCH Cast

EDVARD MUNCH EDVARD MUNCH Cast EDVARD MUNCH Geir Westby MRS. HEIBERG Gros Fraas The Munch Family in 1868 The Munch Family in 1875 SOPHIE Kjersti Allum SOPHIE Inger Berit Oland EDVARD Erik Allum EDVARD Åmund Berge LAURA Susan Troldmyr LAURA Camilla Falk PETER ANDREAS Ragnvald Caspari PETER ANDREAS Erik Kristiansen INGER Katja Pedersen INGER Anne Marie Dæhli HOUSEMAID Hjørdis Ulriksen The Munch Family in 1884 Also appearing DR. CHRISTIAN MUNCH Johan Halsbog ODA LASSON Eli Ryg LAURA CATHRINE MUNCH Gro Jarto CHRISTIAN KROHG Knut Kristiansen TANTE KAREN BJØLSTAD Lotte Teig FRITZ THAULOW Nils Eger Pettersen INGER MUNCH Rachel Pedersen SIGBJØRN OBSTFELDER Morten Eid LAURA MUNCH Berit Rytter Hasle VILHELM KRAG Håkon Gundersen PETER ANDREAS MUNCH Gunnar Skjetne DR. THAULOW Peter Esdaile HOUSEMAID Vigdis Nilssen SIGURD BØDTKER Dag Myklebust JAPPE NILSSEN Torstein Hilt MISS DREFSEN Kristin Helle-Valle AASE CARLSEN Ida Elisabeth Dypvik CHARLOTTE DØRNBERGER Ellen Waaler The Bohemians of Kristiania Patrons of the Café "Zum Schwarzen Ferkel" HANS JÆGER Kåre Stormark AUGUST STRINDBERG Alf Kåre Strindberg DAGNY JUELL Iselin von Hanno Bast STANISLAV PRZYBYSZEWSKI Ladislaw Rezni_ek Others BENGT LIDFORS Anders Ekman John Willy Kopperud Asle Raaen ADOLF PAUL Christer Fredberg Ove Bøe Axel Brun DR. SCHLEICH Kai Olshausen Arnulv Torbjørnsen Geo von Krogh DR. SCHLITTGEN Hans Erich Lampl Arne Brønstad Eivind Einar Berg RICHARD DEHMEL Dieter Kriszat Tom Olsen Hjørdis Fodstad OLA HANSSON Peter Saul Hassa Horn jr. Ingeborg Sandberg LAURA MARHOLM Merete Jørgensen Håvard Skoglund Marianne Schjetne Trygve Fett Margareth Toften Erik Disch Nina Aabel Pianist: Einar Henning Smedby Peter Plenne Pianist: Harry Andersen We also wish to thank the men, women and children of Oslo and Åsgårdstrand who appear in this film. -

Edvard Munch.Pdf

EDVARD MUNCH L.O. TO USE PAINT APPLICATION TECHNIQUES TO CREATE MOOD AND ATMOSPHERE IN A PAINTING WHO IS EDVARD MUNCH WHAT CAN WE REMEMBER FROM THE VIDEO WHAT CAN WE REMEMBER FROM THE VIDEO Born 12.12.1863 His genre of Art is Expressionist Died 23.1 1944 A lot of his art was based on emotions His based some of his art on ghost stories Born in Norway that he loved hearing from his father. Melacholy Jealousy The Scream Anxiety Sickness Death Lonliness Today we are going to have a go at creating our own Scream painting. You will be following the steps of creating the background. Then you can either have you photograph taken in the scream pose or draw your own scream person. He painted one of the most famous and recognized paintings of all time, “The Scream”. This is what he wrote in his diary about the incident that inspired him to paint it: “I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun went down. I felt a gust of melancholy. Suddenly the sky turned a bloody red. I stopped, leaned against the railing, tired to death as the flaming skies hung like blood and sword over the blue-black fjord and the city. My friends went on. I stood trembling with anxiety and I felt a vast infinite scream through nature.” -Edvard Munch. Step 1 create the straight lines for the fence. Sketch them in gentley so you can see them but they will be covered when you paint Step 2. Once you have sketched the fence, paint in the fence, the pathway in shades of brown. -

The Study of the Relationship Between Arnold Schoenberg and Wassily

THE STUDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ARNOLD SCHOENBERG AND WASSILY KANDINSKY DURING SCHOENBERG’S EXPRESSIONIST PERIOD D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sohee Kim, B.M., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2010 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Donald Harris, Advisor Professor Jan Radzynski Professor Arved Mark Ashby Copyright by Sohee Kim 2010 ABSTRACT Expressionism was a radical form of art at the start of twentieth century, totally different from previous norms of artistic expression. It is related to extremely emotional states of mind such as distress, agony, and anxiety. One of the most characteristic aspects of expressionism is the destruction of artistic boundaries in the arts. The expressionists approach the unified artistic entity with a point of view to influence the human subconscious. At that time, the expressionists were active in many arts. In this context, Wassily Kandinsky had a strong influence on Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg‟s attention to expressionism in music is related to personal tragedies such as his marital crisis. Schoenberg solved the issues of extremely emotional content with atonality, and devoted himself to painting works such as „Visions‟ that show his anger and uneasiness. He focused on the expression of psychological depth related to Unconscious. Both Schoenberg and Kandinsky gained their most significant artistic development almost at the same time while struggling to find their own voices, that is, their inner necessity, within an indifferent social environment. Both men were also profound theorists who liked to explore all kinds of possibilities and approached human consciousness to find their visions from the inner world. -

Edvard Munch

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1972 Edvard Munch: Motifs and Motivations Gordon Moffett Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Art at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Moffett, Gordon, "Edvard Munch: Motifs and Motivations" (1972). Masters Theses. 3848. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3848 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements. Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ----- Date Author EDVARD MUNCH: MOTIFS AND MOTIVATIONS (TITLE) BY Gordon Moffett _,.- THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS .---:_.··-- . -

Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety, and Myth

Janet Whitmore exhibition review of Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety, and Myth Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009) Citation: Janet Whitmore, exhibition review of “Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety, and Myth,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009), http://www.19thc- artworldwide.org/autumn09/becoming-edvard-munch-influence-anxiety-and-myth. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Whitmore: Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety, and Myth Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009) Becoming Edvard Munch, Influence, Anxiety and Myth The Art Institute of Chicago 14 February-26 April 2009 Catalogue: Becoming Edvard Munch, Influence, Anxiety and Myth Jay A. Clarke New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009. 232 pages; 245 color and 48 b/w illus; chronology, checklist of exhibition; bibliography; index of works. $50.00 ISBN: 978-0-300-11950-3 We all know the script: unstable artistic personality suffers through self-destructive life while producing tormented, but brilliant, artwork. It is the stuff of La Bohème, Lust for Life, and endless biographies of [pick one] Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Frida Kahlo, Jackson Pollack, Andy Warhol, etc., etc., etc. The cliché of the romantic suffering artist has become a signature trope of western art history as well as popular culture. -

Symbol, Munch & Creativity. Metabolism of Visual Symbols

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 139 Sari Kuuva Symbol, Munch and Creativity Metabolism of Visual Symbols JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 139 Sari Kuuva Symbol, Munch and Creativity Metabolism of Visual Symbols Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Juomatehtaalla, salissa JT120 toukokuun 3. päivänä 2010 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in building Juomatehdas, hall JT120, on May 3, 2010 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2010 Symbol, Munch and Creativity Metabolism of Visual Symbols JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 139 Sari Kuuva Symbol, Munch and Creativity Metabolism of Visual Symbols UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2010 Editor Annika Waenerberg Department of Arts and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Pekka Olsbo Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Tarja Nikula, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä Cover pictures by Edvard Munch URN:ISBN:978-951-39-3865-9 ISBN 978-951-39-3865-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-3847-5 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright © 2010 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2010 !"#$"" %&"(&!)"#%&"(&*+/+*6:;< =%&"(&">" ?@/GQ6FG31X/6Z ?[@978-951-39-3865-9 (PDF), 6\QF6Q/F6FQG\FQ(nid. -

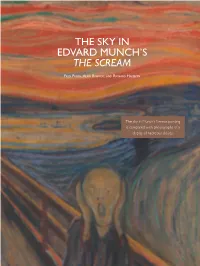

The Sky in Edvard Munch's the Scream

THE SKY IN EDVARD MUNCH’S THE SCREAM FRED PRATA, ALAN ROBOCK, AND RICHARD HAMBLYN The sky in Munch’s famous painting is compared with photographs of a display of nacreous clouds. ABSTRACTS IMPORTANCE OF LATE FALL However, since 1900 neither ob- THE SKY IN EDVARD ENSO TELECONNECTION served CONUS landfalling hur- MUNCH’S THE SCREAM IN THE EURO-ATLANTIC ricane frequency nor intensity The Scream is a well-known paint- SECTOR shows significant trends, including ing by Edvard Munch (1863–1944). Recent studies have indicated the the devastating 2017 season. The Norwegian word used by importance of fall climate forcings Two large-scale climate modes Munch is “skrik,” which can be and teleconnections in influenc- that have been noted in prior translated as “shriek” or “scream.” ing the climate of the northern research to significantly impact The Scream may be of interest mid- to high latitudes. Here, we CONUS landfalling hurricane ac- to meteorologists because of the present some exploratory analy- tivity are El Niño–Southern Oscil- quite striking representation of ses using observational data and lation on interannual time scales the sky. It has been suggested seasonal hindcasts, with the aim and the Atlantic multidecadal that the dramatic red-colored sky of highlighting the potential of oscillation on multidecadal time was inspired by a volcanic sunset the El Niño–Southern Oscilla- scales. La Niña seasons tend to be seen by Munch after the Krakatau tion (ENSO) as a driver of climate characterized by more CONUS eruption in 1883 and by a sighting variability during boreal late fall hurricane landfalls than El Niño of stratospheric nacreous clouds, and early winter (November and seasons, and positive Atlantic mul- and also that it is part of the artist’s December) in the North Atlantic– tidecadal oscillation phases tend expression of a scream from na- European sector, and motivating to have more CONUS hurricane ture. -

XRF Hits: Zn Non-‐Reported W No

Unintended contamination? A selection of Munch’s paintings with non-original zinc white Tine Frøysaker Conservation Studies, Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History (IAKH), University of Oslo Background Among the paintings by Munch owned by public institutions in Oslo, there are two well-documented cases of the presence of non-original zinc white (ZnO): the university’s Aula painting entitled Chemistry (1914-16,1 Fig. 1) and the Munch Museum’s version of Puberty (1894,2 Fig. 2).3 Zinc-containing applications were introduced by a small group of Norwegian restorers and conservators, who applied zinc white (in spite of its ‘seeding’4 effect) to the versos of sever- al paintings during a period of more than 50 years. Zinc white was probably used as an antiseptic additive, although never referred to as such. The first known example is Munch’s Chemistry and ZnO was also applied to the reverse side of the other 10 Aula paintings during the mid 1920s while the paintings (c. 220 m2 in total) were lying on the Aula floor.5 The last reported application was in 1977 to Munch’s History,6 a painted Aula sketch in the Stenersen Collec- tion.7 Conservation records for the Munch paintings at the Munch Museum, the Stenersen Collection and the Bergen Art Museum hold information on two paste-lined paintings each and where zinc white is mentioned as part of the lining-adhesive recipes.8 This poster will consider the phenomenon of non-original ZnO in Munch’s paintings, which undoubtedly points to less-thoroughly reported examples of zinc-contaminated paintings in Norwegian museums.9 Metal soaps and oxalates The presence of zinc across the surface of some of Munch’s paintings was first detected in 2008 and 2009 when the EU- Ac- cess, Research and Technology for the conservation of the European Culture Heritage (EU-ARTECH MOLAB) research team examined Chemistry and Puberty. -

Exposing Motherhood in Nineteenth Century Europe

Woman, demonstrating a shift in the nature of moth- Munch’s Madonna: erhood: that from a moral duty towards an option in a Exposing Motherhood in woman’s life. The methodologies of iconography and Nineteenth Century Europe feminism unravel the symbolically-charged painting, and serve as a means to understand the social impli- cations of motherhood in nineteenth-century Europe. Helena Gomez Where does Munch’s Madonna fit in the con- text of nineteenth-century cultural ambivalence to- wards the emerging New Woman? Although much of Munch’s work has been viewed in a misogynis- tic light, criticized as the objectification of women in the extreme, and seen as a threat to the sanctity of motherhood, there may be room for more subtle in- terpretation. Munch’s Madonna reflects the changing role of motherhood as a social arrangement, and the exploration of the feminine through the New Woman. Late nineteenth-century Europe was charac- terized by the slow decline of Church power since The Virgin Mary, icon of purity and paradig- the French Revolution, modern developments in sci- matic image of the unconditional loving and caring ence, and acceptance of physical and biological hu- mother, represents the idealization of motherhood par man needs; but more importantly, there emerged an excellence. Characterized since Renaissance Mario- ambivalent atmosphere governing the male popula- logical imagery as the embodiment of chastity, she tion around the phenomenon of the New Woman.1 is most often depicted as soft, delicate, fully clothed, The New Woman introduced new tenets of social, and accompanied by the Christ Child. -

Reactions to the Modern World-Post-Impressionism and Expressionism" (2020)

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Art Appreciation Open Educational Resource 2020 Lesson 17 Part 2: Reactions to the Modern World-Post- Impressionism and Expressionism Marie Porterfield Barry East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/art-appreciation-oer Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Editable versions are available for this document and other Art Appreciation lessons at https://dc.etsu.edu/art-appreciation-oer. Recommended Citation Barry, Marie Porterfield, "Lesson 17 arP t 2: Reactions to the Modern World-Post-Impressionism and Expressionism" (2020). Art Appreciation Open Educational Resource. East Tennessee State University: Johnson City. https://dc.etsu.edu/art-appreciation-oer/19 This Book Contribution is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Appreciation Open Educational Resource by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Reactions to the Modern World Post Impressionism and Expressionism” is part of the ART APPRECIATION Open Educational Resource by Marie Porterfield Barry East Tennessee State University, 2020 Introduction This course explores the world’s visual arts, focusing on the development of visual awareness, assessment, and appreciation by examining a variety of styles from various periods and cultures while emphasizing the development of a common visual language. The materials are meant to foster a broader understanding of the role of visual art in human culture and experience from the prehistoric through the contemporary. -

![The Prints of Edvard Munch : [Checklist of the Exhibition], February 13-April 29, 1973](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1081/the-prints-of-edvard-munch-checklist-of-the-exhibition-february-13-april-29-1973-5041081.webp)

The Prints of Edvard Munch : [Checklist of the Exhibition], February 13-April 29, 1973

The prints of Edvard Munch : [checklist of the exhibition], February 13-April 29, 1973 Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1973 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1725 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art SELF-PORTRAIT. 1895 THEPRINTS OF EDUARDMUNCH Hit / 0 PLl f ACKNOWLEDGMENTS On behalf of the Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art, I wish to express my gratitude to the Norwegian Government and to the Munch Museum of the Oslo Municipal Collections, its Director Pal Hougen and his assistant Bente Torjusen, for making available material from their archives. For their invaluable assistance I also wish to thank Dr. and Mrs. David Abrahamsen, New York, Mr. and Mrs. P. Irgens Larsen, New York, Mr. and Mrs. Lionel Epstein, Washington, D. C. , Eleanor Garvey of The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and Bjj2frn Jensen, Director of the Norwegian Information Service in the United States. Among many sources available, the studies of Dr. Reinhold Heller of The University of Pitts burgh have been extremely useful. I am most indebted to Mr. and Mrs. William B. Jaffe for their generous gifts to the Museum and to William S. Lieberman, the Museum's Chief Curator of Drawings, who has been largely respon sible for the formation of its Munch collection. Finally, I would like to thank Howardena Pindell, Assistant Curator in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, for her work on the exhibition. -

Anxiety (Angst)

ART AND IMAGES IN PSYCHIATRY SECTION EDITOR: JAMES C. HARRIS, MD Anxiety (Angst) Sickness, insanity and death were the dark angels standing guard at my cradle and they have followed me throughout my life. Edvard Munch, age 70 years1(p31) ORN IN LØTEN,NORWAY,EDVARD MUNCH Munch began painting at age 17 years in Christiania (1863-1944) was the first Scandinavian (now Oslo). A state grant awarded in 1885 enabled him to painter to establish an international reputa- study in Paris, France. For 20 years thereafter, Munch tion. His artistic creativity spanned more than worked chiefly in Paris and Berlin, Germany. Initially in- 6 decades. During those years, he estab- fluenced by Impressionism and Postimpressionism, he later Blished his reputation as a portraitist and landscape painter developed his highly personal Expressionistic style and con- and painstakingly explored the human passions. Munch tent that emphasized images of illness, anxiety, and death. strongly influenced the development of German Expres- In 1892, an exhibition of his paintings in Berlin so shocked sionism. His life was filled with separation and loss, and the authorities that the show was closed. these experiences are reflected in his art. The second of His painting The Scream carefully reconstructs a 5 children, he was traumatized by the death of his mother moment of anxiety in which he stood alone and trem- when he was 5 years of age and that of his 15-year-old sis- bling.4 The Scream shows the panic experienced when ter, Sophie, at age 14 years. Both died of tuberculosis, a one individual feels totally isolated.