A Conversation with David Leach by Gary Hatcher Prizewinning Traditional Carved and Smoke-Fired Jar by Tammy Garcia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Contemporary Japanese Ceramics

Free admission harn.ufl.edu 3259 Hull Road Gainesville, FL 32611 Front: Hoshino Kayoko, Yakishime ginsai bachi (Unglazed bowl with silver glaze) (detail), 2009, on loan from the collection of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz Back: Yagi Kazuo, Kakiotoshi hoko (Square vessel with etched patterning) (detail), 1966, on loan from the collection of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz The Harn Museum would like to thank Joan Mirviss for her editorial assistance with this guide. Into the Fold: Contemporary Japanese Ceramics from the Horvitz Collection and this guide are generously supported by the Jeffrey Horvitz Foundation. Photos by Randy Batista. About the Author Tomoko Nagakura is a curator and professor of Japanese art. She is currently a Research Fellow for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and has worked on the Jeffrey and Carol Horvitz Collection of contemporary Japanese ceramics since 2012. Previously, she has been a curator at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, as well as other art institutions in Japan. Understanding Contemporary Koike Shōko, Shiro no Shell Japanese Ceramics (White Shell) (detail), 2013, on loan from the collection of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz Tomoko Nagakura Into the Fold: Contemporary Japanese Living National Treasures Female Artists At historically important kiln sites such The increased influence of women artists is another Ceramics from the Horvitz Collection as Shigaraki, Seto (in Aichi Prefecture), important dimension in the development of ceramic art Mino (in Gifu Prefecture), and Bizen in postwar Japan. After the war, secondary education October 7, 2014 – July 15, 2016 (in Okayama Prefecture), artists from was open to a wider population. -

Ishikawa Access Map Kanazawa City Center

Golf Courses KANAZAWA CITY CENTER MAP A great number of scenic golf courses exist in Ishikawa, taking advantage of the many magnificent natural landscapes. Imagine golfing on top of a hill in Noto with shots seemingly descending down to the Sea of Japan, or at the foot of Mt. Hakusan where golfers dauntlessly shoot towars the massive mountainous background. Ishikawa of- 15 16 fers you a unique opportunity to not just play golf, but be one with nature as well! HEGURAJIMA Island The Country Club Noto Kanazawa Links Golf Club ❶● ⓭● 17 14 0768-52-3131 076-237-2222 http://www.cc-noto.co.jp/ Hotel Kanazawa ⓮● Kanazawa 6 ❷● Notojima Golf and Central Country Club 18 Asanogawa Country Club 076-251-0011 River Wajima 0767-85-2311 Kanazawa Kobo-Nagaya Senmaida Rice http://www.notojima-golf.jp/ ● Hakusan Country Club Hyakuban-gai 0761-51-4181 Shopping Mall Terrece http://www.incl.ne.jp/golf/haku/haku1.html ❸● Tokinodai Country Club 13 Suzuyaki Museum 0767-27-1121 4 of Art http://www.tokinodai.co.jp/ ● Kaga Huyo Country Club Wajima 0761-65-2020 2 12 Onsen ❹● Wakura Golf Club 3 0767-52-2580 ● Twin Fields Golf Club 2 Suzu 0761-47-4500 7 Mitsuke-jima http://www.wakuragolfclub.co.jp/ 1 5 Onsen http://www.twin-fields.com/ Hotel Nikko 19 Island ❺● Noto Golf Club Ishikawa Wajima Urushi 0767-32-1212 ● Komatsu Country Club ANA Crowne Plaza Hotel Museum of Art http://www.daiwaresort.co.jp/noto-gc/ 0761-43-3030 5 NANATSUJIMA ❻● Chirihama Country Club ● Komatsu Public Golf Course Island 0767-28-4411 0761-65-2277 10 ❼● Noto Country Club ● Kaga Country Club 0767-28-3155 -

Hamada Shōji (1894-1978)

HAMADA SHŌJI (1894-1978) Hamada Shōji attained unsurpassed recognition at home and abroad for his folk art style ceramics. Inspired by Okinawan and Korean ceramics in particular, Hamada became an important figure in the Japanese folk arts movement in the 1960s. He was a founding member of the Japan Folk Art Association with Bernard Leach, Kawai Kanjirō, and Yanagi Soetsu. After 1923, he moved to Mashiko where he rebuilt farmhouses and established his large workshop. Throughout his life, Hamada demonstrated an excellent glazing technique, using such trademark glazes as temmoku iron glaze, nuka rice-husk ash glaze, and kaki persimmon glaze. Through his frequent visits and demonstrations abroad, Hamada influenced many European and American potters in later generations as well as those of his own. 1894 Born in Tokyo 1912 Saw etchings and pottery by Bernard Leach in Ginza, Tokyo 1913 Studied at the Tokyo Technical College with Itaya Hazan (1872-1963) Became friends with Kawai Kanjiro (1890-1966) and visits in Kyoto (1915) 1914 Became interested in Mashiko pottery after seeing a teapot at Hazan's home 1916 Graduated from Tokyo Technical College and enrolled at Kyoto Ceramics Laboratory, visits with Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886-1963) Began 10,000 glaze experiments with Kawai 1917 Visited Okinawa to study kiln construction 1919 Met Bernard Leach (1887-1979) at his Tokyo exhibition, invited to him his studio in Abiko where meets Yanagi Sōetsu (1889-1961) Traveled to Korea and Manchuria, China with Kawai 1920 Visited Mashiko for the first time Traveled to England with Leach, built a climbing kiln at St. Ives 1923 Traveled to France, Italy, Crete, and Egypt after his solo exhibition in London 1924 Moved to Mashiko. -

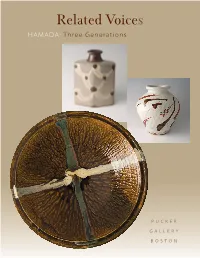

Related Voices Hamada: Three Generations

Related Voices HAMADA: Three Generations PUCKER GALLERY BOSTON Tomoo Hamada Shoji Hamada Bottle Obachi (Large Bowl), 1960-69 Black and kaki glaze with akae decoration Ame glaze with poured decoration 12 x 8 ¼ x 5” 4 ½ x 20 x 20” HT132 H38** Shinsaku Hamada Vase Ji glaze with tetsue and akae decoration Shoji Hamada 9 ¾ x 5 ¼ x 5 ¼” Obachi (Large Bowl), ca. 1950s HS36 Black glaze with trailing decoration 5 ½ x 23 x 23” H40** *Box signed by Shoji Hamada **Box signed by Shinsaku Hamada All works are stoneware. Three Voices “To work with clay is to be in touch with the taproot of life.’’ —Shoji Hamada hen one considers ceramic history in its broadest sense a three-generation family of potters isn’t particularly remarkable. Throughout the world potters have traditionally handed down their skills and knowledge to their offspring thus Wmaintaining a living history that not only provided a family’s continuity and income but also kept the traditions of vernacular pottery-making alive. The long traditions of the peasant or artisan potter are well documented and can be found in almost all civilizations where the generations are to be numbered in the tens or twenties or even higher. In Africa, South America and in Asia, styles and techniques remained almost unaltered for many centuries. In Europe, for example, the earthenware tradition existed from the early Middle Ages to the very beginning of the 20th century. Often carried on by families primarily involved in farming, it blossomed into what we would now call the ‘slipware’ tradition. The Toft family was probably the best known makers of slipware in Staffordshire. -

The Leach Pottery: 100 Years on from St Ives

The Leach Pottery: 100 years on from St Ives Exhibition handlist Above: Bernard Leach, pilgrim bottle, stoneware, 1950–60s Crafts Study Centre, 2004.77, gift of Stella and Nick Redgrave Introduction The Leach Pottery was established in St Ives, Cornwall in the year 1920. Its founders were Bernard Leach and his fellow potter Shoji Hamada. They had travelled together from Japan (where Leach had been living and working with his wife Muriel and their young family). Leach was sponsored by Frances Horne who had set up the St Ives Handicraft Guild, and she loaned Leach £2,500 as capital to buy land and build a small pottery, as well as a sum of £250 for three years to help with running costs. Leach identified a small strip of land (a cow pasture) at the edge of St Ives by the side of the Stennack stream, and the pottery was constructed using local granite. A tiny room was reserved for Hamada to sleep in, and Hamada himself built a climbing kiln in the oriental style (the first in the west, it was claimed). It was a humble start to one of the great sites of studio pottery. The Leach Pottery celebrates its centenary year in 2020, although the extensive programme of events and exhibitions planned in Britain and Japan has been curtailed by the impact of Covid-19. This exhibition is the tribute of the Crafts Study Centre to the history, legacy and continuing significance of The Leach Pottery, based on the outstanding collections and archives relating firstly to Bernard Leach. -

Bernard Leach and His Circle

Bernard Leach and his Circle Spring 2008 26 January – 11 May 2008 Notes for Teachers Information and practical ideas for groups Written by Angie MacDonald Ceramics by Bernard Leach and key studio potters who worked alongside him can be seen in the Showcase (Upper Gallery 2). These works form part of the Wingfield-Digby Collection, recently gifted to Tate St Ives. For discussion • There has been much discussion in recent years as to whether ceramics is an art or a craft. Leach insisted that he was an ‘artist-potter’ and he always regarded his individual pots as objects of art rather than craft. • Why do you think he considered these pots more important than the standard ware (tableware)? • What do you think the display at Tate St Ives says about the status of these objects? Are they sculptures or domestic objects? • The Japanese critic Soetsu Yanagi complimented Leach by describing his earthenware as ‘born not made’. What do you think he meant by this? • Leach said he wanted his pots to have ‘vitality’ – to capture a sense of energy and life. Can you find examples that you feel have this quality? • The simplified motif of a bird was a favourite for Leach. He considered it a symbol of freedom and peace. Can you find other motifs in his work and what do you think they symbolise? Things to think about This stoneware tile has the design of a bird feeding its young, painted in iron. It has sgraffito detailing where Leach scratched through the wet clay slip before firing. It is an excellent example of Leach’s commitment to quiet, contemplative forms with soft, muted colours derived from the earth. -

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition in Modern Japanese Ceramics of the Postwar Period Comparison of a Vase by Hamada Shōji and a Jar by Kitaōji Rosanjin Grant Akiyama Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory, School of Art and Design Division of Art History New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University Alfred, New York 2017 Grant Akiyama, BS Dr. Hope Marie Childers, Thesis Advisor Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the patience and wisdom of my advisor, Dr. Hope Marie Childers. I thank Dr. Meghen Jones for her insights and expertise; her class on East Asian crafts rekindled my interest in studying Japanese ceramics. Additionally, I am grateful to the entire Division of Art History. I thank Dr. Mary McInnes for the rigorous and unique classroom experience. I thank Dr. Kate Dimitrova for her precision and introduction to art historical methods and theories. I thank Dr. Gerar Edizel for our thought-provoking conversations. I extend gratitude to the libraries at Alfred University and the collections at the Alfred Ceramic Art Museum. They were invaluable resources in this research. I thank the Curator of Collections and Director of Research, Susan Kowalczyk, for access to the museum’s collections and records. I thank family and friends for the support and encouragement they provided these past five years at Alfred University. I could not have made it without them. Following the 1950s, Hamada and Rosanjin were pivotal figures in the discourse of American and Japanese ceramics. -

Bernard Leach and British Columbian Pottery: an Historical Ethnography of a Taste Culture

BERNARD LEACH AND BRITISH COLUMBIAN POTTERY: AN HISTORICAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF A TASTE CULTURE by Nora E. Vaillant B. A. Swarthmore College, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Department of Anthropology and Sociology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia October 2002 © Nora E. Vaillant, 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of J^j'thiA^^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This thesis presents an historical ethnography of the art world and the taste culture that collected the west coast or Leach influenced style of pottery in British Columbia. This handmade functional style of pottery traces its beginnings to Vancouver in the 1950s and 1960s, and its emergence is embedded in the cultural history of the city during that era. The development of this pottery style is examined in relation to the social network of its founding artisans and its major collectors. The Vancouver potters Glenn Lewis, Mick Henry and John Reeve apprenticed with master potter Bernard Leach in England during the late fifties and early sixties. -

Of Gallery Marianne Heller

GALLERY 1978 – 2013 35th ANNIVERSARY OF GALLERY MARIANNE HELLER t is always enthusiastic individuals who make a difference. Walter H. Lokau Marianne Heller is just such an enthusiastic individual who Isets things in motion. As a gallery owner, she has dedicated herself to publicising contemporary international ceramics, and she The tale of someone who has been doing this for 35 years. One thing has remained in all this time: her untiring enthusiasm for contemporary ceramics and her set out to bring the world uncompromising desire to make quality ceramics accessible to the public that are otherwise rare in this part of the world. That is what of ceramics to Germany … has remained, but quite a lot of other things have changed in three and a half decades… chael Casson, David Frith, John Maltby, Svend Bayer and oth- The 1970s – the time of self-fulfilment. A passion for peasant ers debuted here with their pots – the whole business grew in pottery had taken hold of Marianne Heller. Were there no contem- no time. Once a year from 1982, the Festhalle in Sandhausen porary ceramics? She looked around. Inevitably a pottery course became the venue for the English Potters' Seminar: a public followed. But she soon left making ceramics herself well alone. By workshop after the English model, and previously unknown in chance, she got her hands on Bernard Leach's A Potter's Book. It was this kind in Germany, intending to teach techniques and at the a revelation! Leach's doctrine of the wheel-thrown vessel, which was same time to develop taste and judgement. -

The Ceramics of KK Broni, a Ghanaian Protégé of Michael

Review of Arts and Humanities June 2020, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 13-24 ISSN: 2334-2927 (Print), 2334-2935 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/rah.v9n1a3 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/rah.v9n1a3 Bridging Worlds in Clay: The Ceramics of K. K. Broni, A Ghanaian protégé of Michael Cardew And Peter Voulkos Kofi Adjei1 Keaton Wynn2 kąrî'kạchä seid’ou1 Abstract Kingsley Kofi Broni was a renowned ceramist with extensive exposure and experience in studio art practice. He was one of the most experienced and influential figures in ceramic studio art in Africa. Broni was trained by the famous Michael Cardew at Abuja, Nigeria, Peter Voulkos in the United States, and David Leach, the son of Bernard Leach, in England. Broni had the experience of meeting Bernard Leach while in England and attended exhibitions of Modern ceramists such as Hans Coper. His extensive education, talent, and hard work, coupled with his diverse cultural exposure, make him one of Africa‘s most accomplished ceramists of the postcolonial era. He is credited with numerous national and international awards. He taught for 28 years in the premiere College of Art in Ghana, at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi. Broni has had an extensive exhibition record and has a large body of work in his private collection. This study seeks to unearth and document the contribution of the artist Kingsley Kofi Broni and position him within the broader development of ceramic studio art in Ghana, revealing the significance of his work within the history of Modern ceramics internationally. -

Gitter : Reflections of a Collector Reflections of a Collector

168 GITTER : REFLECTIONS OF A COLLECTOR REFLECTIONS OF A COLLECTOR kurt a. gitter www.japaneseartsoc.org n July of 2016, Kurt Gitter submitted to Impressions a lengthy memoir of his decades of collecting, principally Japanese art. Our initial communications that summer evolved into a conversation that went on for the next year and a half. We thank Dr. Gitter and his wife and Icollecting partner, Alice Yelen Gitter, for granting Impressions this exclusive interview in the midst of their many other projects (figs. 1, 2a, b). As he prefaced his responses to our exchange: America, Inc. f My 2015 retirement from my fifty-year practice as an ophthalmologist- retinal eye surgeon has afforded me significant time for careful reflection on one of my greatest passions, the collecting of Japanese art. At first, I started thinking more about the facts of my background and initial exposure to Japan and its cultural traditions. Eventually, I came to see that my collecting has as much to do with the remarkable relationships I have developed with numerous individuals—dealers, collectors, scholars. It is my hope that these reflections convey my deep love of the art and culture of Japan and the privilege I feel to have pursued this passion with the help of so many. Was there a precise start to your interest in Japan? 2018 Japanese Art Society o Just after June 1963, I finished my internship at Maimonides Hospital © in Brooklyn and immediately was drafted into the U.S. Air Force. I was twenty-six and married to the late Millie Hyman. -

Hayashi Yasuo and Yagi Kazuo in Postwar Japanese Ceramics: the Effects of Intramural Politics and Rivalry for Rank on a Ceramic Artist’S Career

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 HAYASHI YASUO AND YAGI KAZUO IN POSTWAR JAPANESE CERAMICS: THE EFFECTS OF INTRAMURAL POLITICS AND RIVALRY FOR RANK ON A CERAMIC ARTIST’S CAREER Marilyn Rose Swan University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.509 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Swan, Marilyn Rose, "HAYASHI YASUO AND YAGI KAZUO IN POSTWAR JAPANESE CERAMICS: THE EFFECTS OF INTRAMURAL POLITICS AND RIVALRY FOR RANK ON A CERAMIC ARTIST’S CAREER" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/15 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known.