WRAP THESIS Scott 2005.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hello, Together with the Team at Warwick University and The

Hello, Together with the team at Warwick University and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon, I'm hugely looking forward to welcoming you next month to Shakespeare and his World, our unique online course based on the collections of the Trust. You can find out more about the Trust and the Shakespeare houses here: http://www.shakespeare.org.uk The course is aimed at everybody from the Shakespeare beginner to teachers of Shakespeare and the seasoned playgoer. In the first week, we'll have a general introduction to Shakespeare's life, world and work, and in each subsequent week we'll be linking a particular theme to a particular play. To get the best out of each week, it would be best to read the play while following the course. Though you'll still learn a lot even if you don't manage to do that - especially if it's a play you've studied before or seen on stage or film. Each week we’ll provide the link to an online edition of each of the plays but, to be honest, any edition will do. If you would like to get started now you can access the plays here: http://www.opensourceshakespeare.org/ For those of you who want to prepare for the course, perhaps even read the plays, the order of the plays we will study are as follows: Week 2: The Merry Wives of Windsor http://bit.ly/FLshakespeareMWW Week 3: A Midsummer Night's Dream http://bit.ly/FLshakespeareMND Week 4: Henry V http://bit.ly/FLshakespeareHenryV Week 5: The Merchant of Venice http://bit.ly/FLshakespeareMoV Week 6: Macbeth http://bit.ly/FLshakespeareMacbeth Week 7: Othello http://bit.ly/FLshakespeareOthello Week 8: Antony & Cleopatra http://bit.ly/FLshakespeareAC Week 9: The Tempest http://bit.ly/FLshakespeareTempest The final week is a general round up and a look at Shakespeare's 'afterlife' - the amazing story of his posthumous fame all around the world. -

Othello and the Green-Eyed Monster of Jealousy

Othello and the Green-Eyed Monster of Jealousy by Richard M. Waugaman his article studies jealousy in Shakespeare’s Othello, showing that knowledge of the true author’s life experiences with the extremes of pathological jeal- Tousy will deepen our understanding and appreciation of this unsettling play. This essay builds on the previous Oxfordian study of Othello by A. Bronson Feld- man, the first psychoanalyst to take up Freud’s call that we re-examine Shakespeare’s works with a revised understanding of who wrote them. Freud cited Othello in his 1922 explanation that “projected jealousy” defends against guilt about one’s actual or fantasized infidelity by attributing unfaithfulness to one’s partner. In Hamlet, Shake- speare anticipates Freud’s formulation when Gertrude says, “So full of artless jealou- sy is guilt” (4.5.21). Freud wrote to Arnold Zweig in 1937 that he was “almost irritated” that Zweig still believed Shakspere of Stratford simply relied on his imagination to write the great plays. Freud explained, “I do not know what still attracts you to the man from Stratford. He seems to have nothing at all to justify his claim [to authorship of the canon], whereas Oxford has almost everything. It is quite inconceivable to me that Shakespeare should have got everything secondhand – Hamlet’s neurosis, Lear’s madness…Othello’s jealousy, etc.” (Freud, Zweig Letters, 140; see also Waugaman, 2017). When Shakespeare scholars acknowledge Freud’s Oxfordian opinions at all, they attack his motives, overlooking Freud’s expectation that Shakespeare’s life experiences would bear a significant relationship to his plays and poetry. -

Jonathan Bate, University of Oxford

[Expositions 10.2 (2016) 1–21] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747–5376 Interview: Jonathan Bate, University of Oxford JOHN-PAUL SPIRO Villanova University Sir Jonathan Bate is Professor of English Literature and Provost of Worcester College, Oxford. As the interview below indicates, he has wide-ranging research interests in Shakespeare and Renaissance Literature, Romanticism, biography and life-writing, eco-criticism, contemporary poetry, and theater history. He is a Governor of the Royal Shakespeare Company and engages frequently with literary questions in the public square. I had the chance to sit down with him in early July 2016 – a week after the Brexit vote – at the Provost’s Lodgings at Worcester College. We discussed his life and work, Shakespeare studies at Oxford, the place of the humanities in higher education, his struggles with writing a biography of Ted Hughes, and current events. Below is a transcript of that conversation. Spiro: What brought you to the study of Shakespeare? Bate: Well, I think, like many literary scholars and, perhaps, humanities academics of all disciplines, great teaching. I was lucky enough in secondary school, high school, to have some brilliant English teachers and a very good drama teacher as well. And so I sort of got hooked on poetry, English literature, at age fifteen, sixteen, seventeen. I was keen on theater as well. I played Macbeth as a sixteen-year-old and there’s nothing like acting in a Shakespeare play for internalizing the language. I think I still know the whole of that play by heart. And so it was fairly obvious that an English degree was going to be the thing for me. -

Wordsworth, Coleridge and the Poetic Revolution

16 OCTOBER 2018 Wordsworth, Coleridge and the Poetic Revolution PROFESSOR SIR JONATHAN BATE FBA CBE In my previous lecture, I suggested that one of the key figures in the ferment that led up to the astonishing decade that began with the fall of the Bastille in 1789 was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose Social Contract laid many of the intellectual foundations of the revolution. I also suggested that, along with the political revolution, there was a revolution in sensibility, in attitudes to the emotions, to women, to sexual relations and to children. I will say more about childhood next time. In the second half of this lecture, I want to return to that remark of A. W. Schlegel concerning Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, which I quoted last time: the novel, he said, was ‘a declaration of the rights of feeling’. Rousseau, too, offered such a declaration in the form of a novel: [2] his Nouvelle Héloïse was the most widely read and widely imitated novels of the eighteenth century. The historian of the book Robert Darnton reckons that it was the bestselling secular book of the entire century, with over seventy editions in print by 1800. The story goes that it was so popular that publishers could not print enough copies to keep up with the demand, so they rented it out by the day or even the hour. Rousseau was overwhelmed with fan mail, telling him of the tears, swoons and ecstasies provoked in his readers. A modern reworking of the medieval story of Héloïse and Abelard, it tells the story of a passionate love affair that crosses the boundaries of class, religious piety and decorum. -

Download a Shakespeare Play to Your Iphone Or Justice to His Life

Professor Jonathan Bate CBE FBA is Provost, Worcester College, University of Oxford. A video of Jonathan Bate extracts from this interview can be found via www.britishacademy.ac.uk/prosperingwisely/bate Q What was the initial spark that made you want to study literature, and Shakespeare in particular? Jonathan Bate It all began at school. I remember the first Shakespeare I did at school was Othello; it was at the time of O-Level. The teacher made us listen to a very old gramophone record, and it was absolutely terrible and I didn’t understand a word of it. But then I started going to the theatre, and suddenly it clicked. We had a very good drama teacher, and I played the part of Macbeth when I was 16, and that was it. There was something about the language of Shakespeare that just grabbed me. There is nothing like performing it, nothing like doing it. I think I still know the whole of Macbeth word-for-word, because I learned the part and you listen to the other parts, and it just enters your skin. Shakespeare was writing for the theatre, he was writing to be performed. And once you see it – or even better, do it – it just comes alive and it stays with you. I am very interested in the classical inheritance of English literature, the way that the renaissance was a great Q discovery of the cultural glories of ancient Greece and So Shakespeare needs to be seen and heard? Rome. Shakespeare, of course, was part of that, because he Jonathan Bate studied the Latin classics at school; they were formative of The key to getting people interested in Shakespeare is him. -

The Public Value of the Humanities

Bate, Jonathan. "Introduction." The Public Value of the Humanities. Ed. Jonathan Bate. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011. 1–14. The WISH List. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849662451.0006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 18:11 UTC. Copyright © Jonathan Bate and contributors 2011. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 Introduction Jonathan Bate (University of Warwick) Seven lean cows In chapter 41 of the Book of Genesis, Pharaoh has two troubling dreams. In the fi rst, seven lean cows rise out of the river and devour seven fat cows. And in the second, seven withered ears of grain swallow up seven healthy ears. Pharaoh sends for experts and wise men, but they are unable to interpret these dreams. Then, however, his chief cupbearer tells him of a young captive Jew named Joseph who has proved himself adept in the art of interpretation. Joseph is called for. He suggests that the dreams are predicting that seven years of abundance will be followed by seven years of famine. Pharaoh should accordingly store up surplus food supplies during the good years. He must fi nd a wise and discerning man to take charge of the process. Pharaoh responds by giving the job to Joseph, who builds massive grain stores in the good years, with the result that Egypt thrives during the years of famine – not least by exporting grain to other countries that have not shown such foresight. -

THE CASE for the FOLIO Jonathan Bate

THE CASE FOR THE FOLIO Jonathan Bate ‘The First Folio remains, as a matter of fact, the text nearest to Shakespeare’s stage, to Shakespeare’s ownership, to Shakespeare’s authority’ (Charlotte Porter and Helen Clarke, preface to their Pembroke Edition, 1903) © Jonathan Bate 2007 THIS ESSAY OFFERS A MORE DETAILED ACCOUNT OF THE EDITORIAL PROBLEM IN SHAKESPEARE THAN THAT PROVIDED ON pp. l-lvii/50-57 OF THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE RSC SHAKESPEARE: COMPLETE WORKS THE QUARTOS The original manuscripts of Shakespeare’s works do not survive: the sole extant composition in his hand is a single scene from Sir Thomas More, a multi-authored play that cannot really be described as ‘his’. Shakespeare only survives because his works were printed. In his lifetime there appeared the following works (all spellings of titles modernized here, numbering inserted for convenience only, sequence of publication within same year not readily established). They were nearly all printed in the compact and relatively low- priced format, which may be thought of as the equivalent of the modern paperback, known as quarto (the term is derived from the fact that each sheet of paper that came off the press was folded to make four leaves): 1] Venus and Adonis (1593) – poem. 2] Lucrece (1594) – poem. 3] The most lamentable Roman tragedy of Titus Andronicus, as it was played by the right honourable the Earl of Derby, Earl of Pembroke and Earl of Sussex their servants (1594) – without the fly-killing scene that appears in the 1623 First Folio. 4] The first part of the contention betwixt the two famous Houses of York and Lancaster, with the death of the good Duke Humphrey, and the banishment and death of the Duke of Suffolk, and the tragical end of the proud Cardinal of Winchester, with the notable rebellion of Jack Cade, and the Duke of York’s first claim unto the crown (1594) – a variant version of the play that in the 1623 First Folio was called The Second Part of Henry the Sixth. -

Romantic Ecocriticism: History and Prospects

This is a repository copy of Romantic ecocriticism: History and prospects. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/134169/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Davies, J (2018) Romantic ecocriticism: History and prospects. Literature Compass, 15 (9). e12489. ISSN 1741-4113 https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12489 © 2018 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Davies J. Romantic ecocriticism: History and prospects. Literature Compass. 2018;15:e12489, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12489. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Romantic Ecocriticism: History and Prospects Abstract This essay examines the origins, development and future of Romantic ecocriticism. -

Btb TED HUGHES

THE STORY BEHIND THE BOOK Ted Hughes The Unauthorised Life by Jonathan Bate An explosive and absorbing biography of one of the greatest poets of the twentieth century, Ted Hughes—drawn from newly opened archives and exclusive interviews and filled with revelatory information about his relationship with Sylvia Plath—which illuminates his life as it was lived, remembered, and reshaped in his art. A love of poetry does not come naturally to teenage boys. But I was the kind of boy who loved hanging out in the woods, looking for foxes and badgers, notching up different species of birds on my twitch list. And I was lucky in my teachers. So when our O Level poetry anthology included some of the classic early poems of Ted Hughes— I worry that I meet many ‘The Thought-Fox’, ‘Hawk Roosting’, ‘Pike’, ‘Skylarks’—I instantly knew that young people nowadays who this was my kind of poetry. Then when I have never heard of Ted was an undergraduate I heard the great Hughes, let alone read him. man read in his granite voice from Crow The purpose of a literary in a little upstairs gallery on a foggy biography is to send readers February night. He signed my copy, back to the original writings of winked at me as he looked at the girl I had the subject, to give the work a taken along in the hope of impressing her, new lease of life. I fervently and wished me luck. A little of his hope that my book will spark a magnetism must have rubbed off because I got a kiss that night. -

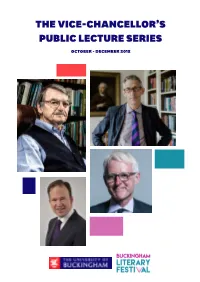

The Vice-Chancellor's Public Lecture Series

THE VICE-CHANCELLOR’S PUBLIC LECTURE SERIES OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2018 PROFESSOR SIR JONATHAN BATE JESSE NORMAN ‘SHAKESPEARE AND THE CLASSICS’ ‘Adam Smith: What he Thought, and Why it Matters’ Tuesday 9 October 2018, 6.30pm Thursday 22 November 2018, 6.30pm The Radcliffe Centre Ian Fairbairn Lecture Theatre, Chandos Road Tickets £5 Tickets £5 Sir Jonathan Bate is Provost of Worcester College and Professor of Adam Smith is now widely regarded as ‘the father of modern economics’ and English Literature in the University of Oxford. He is a Fellow of the the most influential economist who ever lived. But what he really thought, and British Academy, a Governor of the Royal Shakespeare Company, what the implications of his ideas are, remain fiercely contested. Was he an broadcasts regularly for the BBC, and has held visiting posts at Yale eloquent advocate of capitalism and the freedom of the individual? Or a prime and UCLA. He has been awarded a CBE for his services to higher mover of ‘market fundamentalism’ and an apologist for inequality and human education and a knighthood for services to literary scholarship. selfishness? Or something else entirely? His many publications include Shakespeare and Ovid, The Genius of Shakespeare, Soul of the Age: A Biography of At a time when economics and politics are ever more polarized between left and right, this book, by offering a the Mind of William Shakespeare and award-winning biographies of the poets John Clare and Ted Hughes. With Eric Smithian analysis of contemporary markets, predatory capitalism and the 2008 financial crash, returns us to first Rasmussen, he edited The RSC Shakespeare: Complete Works. -

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE and OTHERS – COLLABORATIVE PLAYS (Ed

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE AND OTHERS – COLLABORATIVE PLAYS (ed. Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen) Palgrave Macmillan 2013 Reviewed by Richard Malim Although consideration of the authorship question is specifically ruled out (page 642, and 732 n.1 but with a plug for the inept travesties by Messrs. Shapiro, and Wells and Edmondson), there is much to exercise the mind that is open to the questions that arise, particularly in Will Sharpe’s essay titled Authorship and Attribution. “The authorship question”, he writes (p.641), “though fuelled by class prejudice is nonetheless fuelled by love, ….. .” The “class prejudice” tag exists only in the minds of ‘orthodox’ Stratfordians, but the opinion contradicts Wells’ and Edmondson’s attempt to dub us “anti-Shakespeareans”. Sharpe continues, “……its accusations of fraud intended to elevate, not condemn the revered works.” I know of no accusations of fraud, save the forgeries of Ireland and Collier which are equally denounced by the ‘orthodox’, although there are occasions when the ‘orthodox’ perhaps innocently truncate quotations, or less innocently transcribe e.g. “moniment” as “monument” in the First Folio introductory poems. Sharpe makes some perceptive and courageous points: “…. as a pseudo-science [attribution studies] is [sic] bedevilled by an uncomfortable fact that many practitioners seem reluctant to acknowledge. Poetry is not a naturally occurring phenomenon: it is an artificial product of deliberate and considered work, and words, as units of measurement, never occur in predictable patterned ways in poetry as nucleotides can be expected to do in a DNA strand. Poetry is at once able to be broken down into units and stubbornly resistant to non-cognitive measurement. -

Donna Lee Brien TEXT Vol 18 No 1

Donna Lee Brien TEXT Vol 18 No 1 Central Queensland University Donna Lee Brien ‘Welcome creative subversions’: Experiment and innovation in recent biographical writing Abstract While biography is popularly understood as a literature that tells straightforward, factual life stories, it is – as a literary form – the site of considerable experimentation. This article maps current biographical experimental practice and enquiry against the background of innovation during the twentieth century. This includes a discussion of the form and craft of biographical innovation, including the practical, theoretical and methodological issues involved, much of which has been contributed by working biographers who also reflect on biographical form through the lens of innovation in their own practice. Keywords: Creative writing, Biography, Life writing, Literary innovation and experimentation Imagination is as much the biographer’s right and duty as the novelist’s – Michael Olmert (2000: C8) Introduction More than thirty years ago, biographer and literary critic Leon Edel eloquently expressed the central puzzle of writing biography: “every life takes its own form and a biographer must find the ideal and unique literary form that will express it” (qtd in Novarr 1986: 165). This declaration came at a particularly fertile time of biographical enquiry, after decades of discussion of the form and craft of biographical writing, including the theoretical, methodological and ethical issues involved, much of which was contributed by working biographers who also reflected on biographical form through the lens of innovation in their own practice. Paradoxically, although biography continues to be the site of considerable experimentation, it is currently widely understood as a literature that tells straightforward, factual stories of lives as written by someone else (Pearsall 1998: 175).