RE-DRAW.03 Fallingwater INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E N G L I S H

Matura Examination 2017 E N G L I S H Advance Information The written Matura examination in English consists of four main sections (total 90 credits in sections I-III): Section I: Listening (credits: 14) Multiple choice and questions Section II: Reading Comprehension (credits: 20) 1. Short answer questions Section III: Use of English (credits: 56) 1. Synonyms 2. Antonyms 3. Word Formation 4. Sentence Transformation 5. Open Cloze Section IV: Writing, approx. 400 words (the mark achieved in this part will make up 50% of the overall mark) Time management: the total time is 240 minutes. We recommend you spend 120 minutes on sections I-III, and 120 minutes on section IV. Write legibly and unambiguously. Spelling is important in all parts of the examination. Use of dictionary: You will be allowed to use a monolingual dictionary after handing in sections I-III. The examination is based on Morgan Meis’s article “Frank Lloyd Wright Tried to Solve the City”, published in the “Critics” section of the May 22, 2014 issue of The New Yorker magazine. Frank Lloyd Wright Tried to Solve the City by MORGAN MEIS In: The New Yorker, May 22, 2014 Frank Lloyd Wright1 hated cities. He thought that they were cramped and crowded, stupidly designed, or, more often, built without any sense of design at all. He once wrote, “To look at the 5 plan of a great City is 5 to look at something like the cross-section of a fibrous tumor.” Wright was always looking for a way to cure the cancer of the city. -

Artistic Evolution at the Confluence of Cultures

Dochaku: Artistic Evolution at the Confluence of Cultures Toshiko Oiyama A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art, College of Fine Arts University of New South Wales 2011 Acknowledgements Had I known the extent of work required for a PhD research, I would have had a second, and probably a third, thought before starting. My appreciation goes to everyone who made it possible for me to complete the project, which amounts to almost all with whom I came in contact while undertaking the project. Specifically, I would like to thank my supervisors Dr David McNeill, Nicole Ellis, Dr Paula Dawson, Mike Esson and Dr Diane Losche, for their inspiration, challenge, and encouragement. Andrew Christofides was kind to provide me with astute critiques of my practical work, while Dr Vaughan Rees and my fellow PhD students were ever ready with moral support. Special thanks goes to Dr Janet Chan for giving me the first glimpse of the world of academic research, and for her insightful comments on my draft. Ms Hitomi Uchikura and Ms Kazuko Hj were the kind and knowledgeable guides to the contemporary art world in Japan, where I was a stranger. Margaret Blackmore and Mitsuhiro Obora came to my rescue with their friendship and technical expertise in producing this thesis. My sister Setsuko Sprague and my mother Nobuko Oiyama had faith in my ability to complete the task, which kept me afloat. Lastly, a huge thanks goes to my husband Derry Habir. I hold him partly responsible for the very existence of this project – he knew before I ever did that I wanted to do a PhD, and knew when and how to give me a supporting hand in navigating its long process. -

Rise of Modernism

AP History of Art Unit Ten: RISE OF MODERNISM Prepared by: D. Darracott Plano West Senior High School 1 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES IMPRESSIONISM Edouard Manet. Luncheon on the Grass, 1863, oil on canvas Edouard Manet shocking display of Realism rejection of academic principles development of the avant garde at the Salon des Refuses inclusion of a still life a “vulgar” nude for the bourgeois public Edouard Manet. Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas Victorine Meurent Manet’s ties to tradition attributes of a prostitute Emile Zola a servant with flowers strong, emphatic outlines Manet’s use of black Edouard Manet. Bar at the Folies Bergere, 1882, oil on canvas a barmaid named Suzon Gaston Latouche Folies Bergere love of illusion and reflections champagne and beer Gustave Caillebotte. A Rainy Day, 1877, oil on canvas Gustave Caillebotte great avenues of a modern Paris 2 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES informal and asymmetrical composition with cropped figures Edgar Degas. The Bellelli Family, 1858-60, oil on canvas Edgar Degas admiration for Ingres cold, austere atmosphere beheaded dog vertical line as a physical and psychological division Edgar Degas. Rehearsal in the Foyer of the Opera, 1872, oil on canvas Degas’ fascination with the ballet use of empty (negative) space informal poses along diagonal lines influence of Japanese woodblock prints strong verticals of the architecture and the dancing master chair in the foreground Edgar Degas. The Morning Bath, c. 1883, pastel on paper advantages of pastels voyeurism Mary Cassatt. The Bath, c. 1892, oil on canvas Mary Cassatt mother and child in flattened space genre scene lacking sentimentality 3 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES Claude Monet. -

Fallingwater/Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

Fallingwater and the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy Designed in 1935, Fallingwater is perhaps Frank Lloyd Wright’s most widely acclaimed work. Fallingwater was created for the Edgar J. Kaufmann family, the owners of the former Pittsburgh department store chain, Kaufmann’s. The site of the house was the Kaufmann family’s mountain property at Bear Run, where they enjoyed weekend and summer vacations. Completed with the guest house and servants’ quarters in 1939, Fallingwater was constructed of native sandstone quarried on the property and laid by local craftsmen. Fallingwater is located on a 5,000- acre natural heritage area, Bear Run Nature Reserve, named for Bear Run, the stream that runs through the reserve. In 1963, Edgar Kaufmann jr., son of the house’s patron, entrusted the house and approximately 1,500 acres surrounding it to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (WPC). Over time, WPC assembled enough parcels of land to create a 20-mile trail system on the reserve that traverses nearly the entire Bear Run watershed. Nearly 10 acres of the reserve directly surround the house. PA State Route 381, a major two-lane transportation route through the mountainous Laurel Highlands, divides most of the remaining acreage from the Fallingwater side. Bear Run Nature Reserve is an area of great natural diversity with stunning outcroppings of Pottsville sandstone. It has significant aquatic and animal life, such as native trout, numerous birds, black bears and bobcats. The flora includes extensive stands Western Pennsylvania Conservancy • 800 Waterfront Drive • Pittsburgh, PA 15222 412-288-2777 • 1-866-564-6972 Toll Free WaterLandLife.org of wildflowers, rhododendron and trees including mature oaks, maples, poplars, dogwoods and hemlocks. -

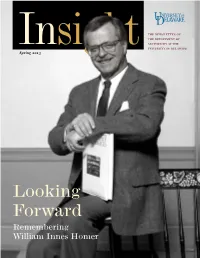

2013 Newsletter

the newsletter of the department of art history at the university of delaware Spring 2013 Looking Forward Remembering William Innes Homer 1 Spring 2013 From the Chair Editor: Camara Dia Holloway Dear friends of the Department of Art History at Editorial Assistant: Amy Torbert the University of Delaware, As you will see from this issue of Insight, it has been Art Director and Project Manager: a busy and eventful year for the faculty and students Christina Jones and former students in the Department. I am writing to you from my temporary position as interim Chair Lawrence Nees. for the next three terms, which I began to occupy in January Photo by George Freeman. Department of Art History Staff: 2013. In the fall of last year our distinguished Professor Nina Linda J. Magner, Starline Griffin Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, who had been serving as Chair for several years, announced that she wished to step down from Photographer: George Freeman that position and, after the sabbatical now beginning, will retire from full-time teaching. Professor Kallmyer has taught at Delaware since 1982 and has brought much distinction to the faculty and immense learning and energy to our students at all levels. She is the Insight is produced by the Department author of four important books, French Images from the Greek War of Independence of Art History as a service to alumni and (1989), Eugène Delacroix: Prints, Politics and Satire (1991), Cézanne and Provence (2003) friends of the Department. We are always and Théodore Géricault (2010), and countless articles, the recipient of many awards, pleased to receive your opinions and including the College Art Association’s (CAA) Arthur Kingsley Porter Prize, and her many The officers of the Art History ideas. -

European Home Look Book

European Home EuropeanFire & ModernHome Interior Design Interior Design Look Book Look Book Gyrofocus by Focus PREFACE Sky T by Element4 Fire & Modern Interior Design This catalog is a celebration of the interior design styles of today. European Home manufactures and imports premium modern fireplaces. Many of the images you will see within these pages are from projects that utilize our fireplaces in creative ways. From Mid-Century Modern to Industrial, we explored the quintessential elements of 10 popular interior design styles and highlighted the role of the fireplace within the context of contemporary interior Kabaz Architecture design. Holly Markham President and Founder European Home STYLES Art Deco ...................................................................................................................... 4 - 5 Contemporary ....................................................................................................... 6 - 7 Industrial ....................................................................................................................... 8 - 9 Mid-Century Modern ................................................................................... 10 - 11 Minimalist ................................................................................................................ 12 - 13 Modern Farmhouse....................................................................................... 14 - 15 Modern Scandinavian ............................................................................... 16 - 17 -

VRA Bulletin 1998

Feature Articles Volume 25 Number 4 VRA Bulletin 1998 The VRA Core Categories for Visual Resources, Version 2.0 October 15, 1997 Visual Resources Association Data Standards Committee © 1997 Visual Resources Association General Guidelines The VRA Core Categories for Visual Resources are intended as a guideline for developing local databases and cataloging records. While they are not specific instructions for system-building or record structures, they may be used as a template for the foundation of such applications. For example, in a flat file database both work and visual document information might reside in a single record, while in a relational database environment, work information may be entered in a separate table and linked to visual document records. The VRA Core Categories for Visual Resources element set contains two groupings of elements, the Work Description Categories (nineteen elements), and the Visual Document Description Categories (nine elements). Because they are guidelines, it is not required that all of the categories be used to create a record for anyone work or visual document. Users may also find the need to supplement the VRA Core with additional elements for a fuller description of the work or visual document. In addition, the same data values may appear in more than one category within a record . In order to facilitate interoperability with other cultural heritage information resources, the VRA Core, Version 2.0, is mapped to the CDWA, MARC, and the REACH Project data element set. How the VRA Core serves as a guide for cataloging practice: • Defining a "work": The Core includes both work and visual document information. -

Frank Lloyd Wright: Kaufmann House / Fallingwater (1936-9)

Video transcript: Frank Lloyd Wright: Kaufmann House / Fallingwater (1936-9) Fallingwater is perhaps Wright’s most iconic domestic commission. As such it seems to epitomise many of the broader architectural themes which ran through his work, and thought, up to this point in his career. The house takes the form of a complex array of interlocking horizontal planes and projecting terraces, each of which extends outwards from a common vertical ‘spine’. This architectonic tension between horizontal and vertical is given material and visual emphasis by means of Wright’s use of starkly contrasting construction materials as regards the central spine as against the horizontal terraces. The central spine, or ‘chimney’, which serves both as the common armature supporting the horizontal terraces, and as and as the structural ‘anchor’ which connects the house as a whole to its surrounding terrain, is composed of roughly textured stone blocks, somewhat reminiscent visually of a dry-stone wall. This both emphasises the physical connection between the house as a unit and the rocky terrain upon which it sits, and also provides a visual metaphor which is appropriate given that this spine is the principal structural armature upon which the house as a whole depends. The roughly hewn stone blocks convey a powerful impression of strength and stability. They also evoke associations with the traditions of American rural domestic architecture. The central chimney-stack around which traditional rural houses were built would, of course, have been composed of just such a material. The horizontal terraces, by contrast, seem to issue from a much more contemporary architectural vernacular. -

Art and Design

Art + De sig n S S World Art History Certificate elective: Earn 1 credit E R G N O C F O Surrealism Y R A R B I The Canvas of Dreams L Surrealism: The chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella! —Les Chants de Maldoror, Comte de Lautreamont, 1869 One of the major art movements of the 20th century, surre - alism opened the door to the exploration of the unconscious and the creation of art based on inner reality. Freud’s dream research liberated surrealist artists to see the truth of who we really are, and in their work, dreams became equivalent to imagination itself. Artist and art historian Joseph Cassar explores the origins of surrealism, its widespread influence, and many of its most prominent artists including Max Ernst, Jean Arp, Joan Miro, Andre Masson, Rene Magritte, Alberto Giacometti, and Salvador Dali. Salvador Dali with Babou, the ocelot, and cane, 1965 9:30 a.m. Metaphysical Art and the Anxieties of the 20th Century 11 a.m. Andre Breton and the Surrealist Manifesto 12:30 p.m. Lunch (participants provide their own) 1:30 p.m. The Surrealist Revolution: Magritte, Ernst, Masson, and Others Woman and Bird, 1982, by Joan 2:45 p.m. Salvador Dali and the Paranoiac-Critical Method Miró, in Barcelona, Spain Sat., June 2, 9:30 a.m.–4 p.m.; Ripley Center; CODE 1H0-341; Members $90; Nonmembers $140 World Art History Certificate core course: Earn 1 credit Italian Renaissance Art The arts blossomed in Renaissance Italy, an era that encompassed the innovations of perspective and oil paint, a new emphasis on the study of anatomy and antiquity, and the growing independ - ence of the artist. -

C:\Working Papers\10515.Wpd

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES A PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A VERY YOUNG OR VERY OLD INNOVATOR: CREATIVITY AT THE EXTREMES OF THE LIFE CYCLE David W. Galenson Working Paper 10515 http://www.nber.org/papers/w10515 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2004 The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. ©2004 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. A Portrait of the Artist as a Very Young or Very Old Innovator: Creativity at the Extremes of the Life Cycle David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 10515 May 2004 JEL No. J4 ABSTRACT Orson Wells made Citizen Kane, his greatest movie, when he was 25 years old; Frank Lloyd Wright designed Fallingwater, his most famous house, when he was 70. Contrasts as great as this raise the question of whether there is a general explanation of when in their lives great innovators are most creative. For each of seven artistic disciplines, this paper examines a major innovation made by a very young artist, and another made by an old one, with the goal of understanding the role of the artist's age and experience in the accomplishment. The analysis shows why youth was necessary for the innovations of such conceptual artists as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Arthur Rimbaud, Maya Lin, and Orson Welles, all of whom produced their masterpieces before the age of 30, and why extensive experience was necessary for the innovations of such experimental artists as Piet Mondrian, Elizabeth Bishop, Henrik Ibsen, and Frank Lloyd Wright, all of whom made major contributions after the age of 60. -

Saturday, October 16

GEARS Saturday, October 16 We will be inspired by the great design works of Frank Lloyd Cost Wright and the “Cresent of Embrace”. As our day unfolds, we will stop at the temporary sight of the new memorial “The Cresent of $145 per person ($152 non-member) Embrace”, which is designed to be a lasting remembrance of courage and heroism from the passengers and crew of flight 93. A luncheon buffet will be served at the famous Trip Includes: Oakhurst Tea Room. Enjoy the fall foliage as we travel to Transportation, Guide Service, Fallingwater, a Frank Lloyd Wright masterpiece. The home is dramatically cantilevered over a waterfall designed and built in Luncheon Buffet, Flight 93 1935. After seeing this remarkable structure, we will travel to Memorial, Fallingwater & Kentuck Knob another fabulous Wright home. Kentuck Knob Kentuck Knob, an excellent example of a high-end Usonian home, was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in the last decade of his career. Kentuck Knob's constructon of native sandstone, To register contact: tidewater cypress, and copper blends naturally with its GEARS surroundings in true Wrightian harmony. A sculpture garden with over 35 major works enhances the visitor's experience. Truly an www.GetintoGEARS.org unforgettable tour. 367-0355 ITINERARY 5:45 AM Depart MoviE-town Cinema Parking Lot Tour the Flight 93 Memorial future site of the “Cresent of Embrace” Enjoy a luncheon Buffet at Oakhurst Tearoom Depart for Fallingwater Tour the magnificent Fallingwater Tour Kentuck Knob & sculpture gardens Depart for Bedford, Drop your guide 6:30 PM Dinner at Hoss’s, Bedford (on own) 7:30 PM Depart for home 9:00 PM Approximate time of arrival home . -

Quotes About Fallingwater

Quotes about Fallingwater “….there are many places where conversation, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s work, can be studied; there is nowhere else where [Fallingwater] his architecture can felt so warmly, appreciated so intuitively. That is the beginning of wisdom. .” Edgar Kaufmann, jr. Fallingwater is a great blessing - one of the great blessings to be experienced here on earth, I think nothing yet ever equalled the coordination, sympathetic expression of the great principle of repose where forest and stream and rock and all the elements of structure are combined so quietly that really you listen not to any noise whatsoever although the music of the stream is there. But you listen to Fallingwater the way you listen to the quiet of the country... Frank Lloyd Wright Talk to the Taliesin Fellowship, May 1, 1955 Fallingwater is famous because the house in its setting embodies a powerful ideal-that people today can learn to live in harmony with nature. .As technology uses more and more natural resources, as the world’s population grows even larger, harmony with nature is necessary for the very existence of mankind. Edgar Kaufmann, jr. It has served well as a house, yet has always been more than that, a work of art beyond any ordinary measure of excellence. Itself an ever-flowing source of exhilaration, it is set on the waterfall of Bear Run, spouting nature’s endless energy and grace. House and site together form the very image of man’s desire to be at one with nature, equal and wedded to nature. Edgar Kaufmann, jr.