World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma

To: Hon. Mr. Ban Ki-moon Secretary-General United Nations From: Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma CC: Mr. B. Lynn Pascoe, Under-Secretary-General, United Nations Mr. Ibrahim Gambari, Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser to the Secretary- General on Myanmar/Burma Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the five Permanent Members (China, Russia, France, United Kingdom and the United states) of the UN Security Council U Aung Shwe, Chairman, National League for Democracy Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, General Secretary, National League for Democracy U Aye Thar Aung, Secretary, Committee Representing the Peoples' Parliament (CRPP) Veteran Politicians The 88 Generation Students Date: 1 August 2007 Re: National Reconciliation and Democratization in Myanmar/Burma Dear Excellency, We note that you have issued a statement on 18 July 2007, in which you urged the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) (the ruling military government of Myanmar/Burma) to "seize this opportunity to ensure that this and subsequent steps in Myanmar's political roadmap are as inclusive, participatory and transparent as possible, with a view to allowing all the relevant parties to Myanmar's national reconciliation process to fully contribute to defining their country's future."1 We thank you for your strong and personal involvement in Myanmar/Burma and we expect that your good offices mandate to facilitating national reconciliation in Myanmar/Burma would be successful. We, Members of Parliament elected by the people of Myanmar/Burma in the 1990 general elections, also would like to assure you that we will fully cooperate with your good offices and the United Nations in our effort to solve problems in Myanmar/Burma peacefully through a meaningful, inclusive and transparent dialogue. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

Grievance Mechanism Procedure (GMP)

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) REPORT PROPOSED 135 MW KYAUK PHYU COMBINED CYCLE POWER PLANT PROJECT AT KYAUK PHYU TOWNSHIP RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) PROPOSED 135 MW KYAUK PHYU COMBINED CYCLE POWER PLANT PROJECT AT KYAUKPHYU TOWNSHIP, RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR REPORT May 2020 Preparedfor Kyauk Phyu Electric Power Company Limited Prepared by ENVIRON Myanmar Company Limited ProjectNumber: ST190002 Environmental Impact Assessment Proposed 135 MW Kyauk Phyu CCPP Project, Kyauk Phyu Township, Rakhine State, Myanmar Contents 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Statement Of Need ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 Project Description .......................................................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 Existing Environment ...................................................................................................................... 1-8 1.5 Assessment of Impacts ................................................................................................................. 1-10 1.6 Environmental Management Plan (EMP) .................................................................................... -

Kyaukpyu Township and Ramree Township Rakhine State

NEPAL BHUTAN INDIA CHINA Myanmar Information Management Unit BANGLADESH VIETNAM Kyaukpyu Township and Ramree Township LAOS THAILAND Rakhine State CAMBODIA 93°30'E 93°40'E 93°50'E Chaung Gyi Hpyar (198722) Thea Tan (198470) (Shwe Nyo Ma) Laung Khoke Taung (Ngwe Twin Tu) (198682) (Thea Tan) (Ya Ta Na) Ywar Thit (198687) (Ya Ta Na) Min Gan (198708) (Min Gan) Chon Swei (198697) (Chon Swei) Lawt Te (198709) La Har Gyi (198715) (Min Gan) (La Har Gyi) Ywar Thit Kay (198716) (La Har Gyi) Ah Nauk Hmyar Tein (198685) (Ya Ta Na) Taung Shey (198725) Nga Hpyin Thet (198718) (War Taung) (La Har Gyi) Ah Shey Hmyar Tein (198683) (Ya Ta Na) Doe Tan (198712) (Min Gan) Ma Ra Zaing (198713) Kon Pa Ni Zay (198466) Ka Nyin Taw (198711) (Min Gan) Mauk Tin Gyi (198714) La Man Chaung (198694) Myone Pyin (198681) (Taung Yin) (Min Gan) (Min Gan) (Pan Taw Pyin) (Ya Ta Na) Kyaukpyu War Taung (198724) (War Taung) Taung Yin (198465) Ka Nyin Taw (198469) Say Poke Kay (198486) (Taung Yin) (Taung Yin) (Gone Chein) Ku Lar Bar Taung (198468) Pyin Hpyu Maw (198464) Kywe Te (198695) Ah Htet Pyin (198483) (Taung Yin) (Pyin Hpyu Maw) (Pan Taw Pyin) (Gone Chein) Ah Shey Bat (198487) Nga/La Pwayt (198467) (Gone Chein) (Taung Yin) Pan Taw Pyin (West) (198692) Ya Ta Na (198680) Aung Zay Di (198488) (Ya Ta Na) (Gone Chein) Lay Dar Pyin (198484) (Pan Taw Pyin) (Gone Chein) Kyauk Tin Seik (198492) Saing Chon Dwain (198542) Ku Toet Seik (198696) Pan Taw Pyin (East) (198693) (Ohn Taw) (Saing Chon) (Pan Taw Pyin) (Pan Taw Pyin) Kone Baung (198493) Saing Chon (North) (198540) (Ohn Taw) -

Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States. in Five

GAZETTEER OF UPPER BURMA AND THE SHAN STATES. IN FIVE VOLUMES. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL PAPERS BY J. GEORGE SCOTT. BARRISTER-AT-LAW, C.I.E., M.R.A.S., F.R.G.S., ASSISTED BY J. P. HARDIMAN, I.C.S. PART II.--VOL. III. RANGOON: PRINTED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BURMA. 1901. [PART II, VOLS. I, II & III,--PRICE: Rs. 12-0-0=18s.] CONTENTS. VOLUME III. Page. Page. Page. Ralang 1 Sagaing 36 Sa-le-ywe 83 Ralôn or Ralawn ib -- 64 Sa-li ib. Rapum ib -- ib. Sa-lim ib. Ratanapura ib -- 65 Sa-lin ib. Rawa ib. Saga Tingsa 76 -- 84 Rawkwa ib. Sagônwa or Sagong ib. Salin ib. Rawtu or Maika ib. Sa-gu ib. Sa-lin chaung 86 Rawva 2 -- ib. Sa-lin-daung 89 Rawvan ib. Sagun ib -- ib. Raw-ywa ib. Sa-gwe ib. Sa-lin-gan ib. Reshen ib. Sa-gyan ib. Sa-lin-ga-thu ib. Rimpi ib. Sa-gyet ib. Sa-lin-gôn ib. Rimpe ib. Sagyilain or Limkai 77 Sa-lin-gyi ib. Rosshi or Warrshi 3 Sa-gyin ib -- 90 Ruby Mines ib. Sa-gyin North ib. Sallavati ib. Ruibu 32 Sa-gyin South ib. Sa-lun ib. Rumklao ib. a-gyin San-baing ib. Salween ib. Rumshe ib. Sa-gyin-wa ib. Sama 103 Rutong ib. Sa-gyu ib. Sama or Suma ib. Sai Lein ib. Sa-me-gan-gôn ib. Sa-ba-dwin ib. Saileng 78 Sa-meik ib. Sa-ba-hmyaw 33 Saing-byin North ib. Sa-meik-kôn ib. Sa-ban ib. -

Village Tracts of Myaing Township Magway Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tracts of Myaing Township Magway Region 94°39’E 94°48’E 94°57’E 95°6’E Salingyi Pale 21°54’N 21°54’N Kyauk Taung Bant Boe Htay Aung Kyauk Kan Ywar Thit Hpya Chaung Son Pan Swar Ywar Shey Hpya Thee Hle Khoke Thee Tone Bone Gyi Kan Taung Kaing Tha Min Chauk Tha Dut Let Yet Ma Te Gyi Than Bo Gyi Paung Tei Sin Swei Lin Ka Taw 21°45’N 21°45’N Ma Gyi Kan Taung Boet Hta Naung Win Ba Hin Wei Taung Su Win Kyi Kan Kyet Mauk Gyoke Shwe Lin Swe Min Thar Kya Kan Ni Thin Ma Seik Chay Oe Bo Kun Taw Htan Taung Son Bone Let Se Kan Inn Yaung MYAING Ta w Gway Pin Lel Ah Lel Kan Myo Soe Myaing (South) Pauk Pyin Thet Kei Kan Sin Sein Kon Lat Tha Nat Pin Kone (North) Urban Htan Bu Seik Sin 21°36’N Ta w 21°36’N Chaing Zauk Sa Bay Daung Oh Wet Poke Tha Yet Kwa Paik Thin Ma Gyi Su Kyan Seint Thin Paung Kan Pay Pin Taik Myo Thar Aing Ma Kyauk Sauk Thit Gyi Taw Wet Kya Kaing Taw Ma Ywar Tan Kan Yar Kaung Shey Hpaung Kwe Myo Tin Mon Hnyin Myauk Nyaung Myay Yint Hnan Si Kan Nyaung Twin Hnaw Pin Oh Yin 21°27’N 21°27’N Twin Ma Da Hat Chauk Kan Tein Sagaing Chin Shan Mandalay Magway Pakokku Bay of Bengal Rakhine Bago Kilometers 21°18’N 06123 21°18’N Ayeyarwady 94°39’E 94°48’E 94°57’E 95°6’E Map ID: MIMU575v01 Legend Data Sources : GLIDE Number: TC-2010-000211-MMR Cyclone BASE MAP - MIMU State Capital Road Village Tract Boundaries Creation Date: 6 December 2010. -

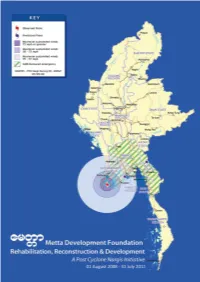

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development a Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 1 2 Metta Development Foundation Table of Contents Forward, Executive Director 2 A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative - Executive Summary 6 01. Introduction – Waves of Change The Ayeyarwady Delta 10 Metta’s Presence in the Delta. The Tsunami 11 02. Cyclone Nargis –The Disaster 12 03. The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 14 04. The Global Proposal 16 The Proposal 16 Connecting Partners - Metta as Hub 17 05. Rehabilitation, Reconstruction and Development August 2008-July 2011 18 Introduction 18 A01 – Relief, Recovery and Capacity Building: Rice and Roofs 18 A02 – Food Security: Sowing and Reaping 26 A03 – Education: For Better Tomorrows 34 A04 – Health: Surviving and Thriving 40 A05 – Disaster Preparedness and Mitigation: Providing and Protecting 44 A06 – Lifeline Systems and Transportation: The Road to Safety 46 Conclusion 06. Local Partners – The Communities in the Delta: Metta Meeting Needs 50 07. International Partners – The Donor Community Meeting Metta: Metta Day 51 08. Reporting and External Evaluation 52 09. Cyclones and Earthquakes – Metta put anew to the Test 55 10. Financial Review 56 11. Beyond Nargis, Beyond the Delta 59 12. Thanks 60 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 61 Staff Directory 62 Volunteers 65 Annex 1 - The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 68 Annex 2 – Maps 76 Annex 3 – Tables 88 Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 3 Forword Dear Friends, Colleagues and Partners On the night of 2 May 2008, Cyclone Nargis struck the delta of the Ayeyarwady River, Myanmar’s most densely populated region. The cyclone was at the height of its destructive potential and battered not only the southernmost townships but also the cities of Yangon and Bago before it finally diminished while approaching the mountainous border with Thailand. -

Covid-19 Response Situation Report 11 | 6 August 2020

IOM MYANMAR COVID-19 RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 11 | 6 AUGUST 2020 10,893 migrants returned from Thailand through border checkpoints from 17 July to 5 August 141,710 migrants returned through border checkpoints to date Migrant Resource Centre (MRC) Counsellor, in coordination with the Department of Labour (DOL), distributing humanitarian assistance to returning migrants in Myawaddy, Kayin State. © IOM 2020 SITUATION OVERVIEW Returns from Thailand continued at a steady pace on the Thailand due to travel restrictions. On 4 August, a Cabinet second half of July and the first week of August, with 10,893 Resolution approved measures for the extension of stay and re- (4,520 female, 6,373 male) returns from 17 July to 5 August. A employment of MOU migrants already in Thailand. But the further 949 Myanmar nationals returned via Myanmar deployment of new MOU migrants still awaits Cabinet Government Assisted Relief flights between 17 to 26 July, approval, and procedures and costs are still being discussed. including from Hong Kong, Singapore, Korea, Australia and The Myanmar Embassy in Thailand is collecting the advance Jordan, among others. Since the middle of March, a total of voting list of Myanmar nationals in Thailand, including of MOU 141,710 migrants have returned to Myanmar via land border migrants, in preparation for the upcoming elections. checkpoints from Thailand (97,342), China (44,051) and Lao PDR (317), with an additional 9,492 Myanmar nationals returning via relief flights. The Myanmar Government extended COVID-19 related restrictions until 15 August. This is the fourth extension and it retains the nationwide 00:00 AM to 4:00 AM curfew, the ban on international commercial flights into Myanmar, the temporary suspension of visas on arrival and e-visas, and the temporary suspensions on overseas employment processes (including MOU recruitment and deployment). -

Township Environmental Assessment 2017

LABUTTA TOWNSHIP ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT 2017 MYANMAR ENVIRONMENT INSTITUTE This report has been prepared by Myanmar Environment Institute as part of BRACED Myanmar Consortium(2015-2017) Final Report Page I Abbreviation and Acronyms BRACED Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters CRA Community Risk Assessment CSO Civil Society Organization CSR Corporate Social Responsibility ECD Environmental Conservation Department EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EU European Union IEE Initial Environmental Examination Inh/km2 Inhabitant per Kilometer Square KBA Key Biodiversity Area MEI Myanmar Environment Institute MIMU Myanmar Information Management Unit MOECAF Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry MONREC Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation NCEA National Commission for Environmental Affair NGO Non-Governmental Organization RIMES Regional Integrated Multi -Hazard Early Warning System SEA Strategic Environmental Assessment TDMP Township Disaster Management Plan TEA Township Environmental Assessment TSP Township Final Report Page II Table of Content Executive Summary ______________________________________________ 1 Chaper 1 Introduction and Background ____________________________ 12 1. 1 Background __________________________________________________________________ 12 1. 2 Introduction of BRACED ________________________________________________________ 13 1. 3 TEA Goal and Objective ________________________________________________________ 15 1. 4 SEA -

Gazetteer of Upper Burma. and the Shan States. in Five Volumes. Compiled from Official Papers by J. George Scott, Barrister-At-L

GAZETTEER OF UPPER BURMA. AND THE SHAN STATES. IN FIVE VOLUMES. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL PAPERS BY J. GEORGE SCOTT, BARRISTER-AT-LAW, C.I.E,M.R.A.S., F.R.G.S., ASSISTED BY J. P. HARDIMAN, I.C.S. PART II.--VOL. I. RANGOON: PRINTRD BY THE SUPERINTENDENT GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BURMA. 1901. [PART II, VOLS. I, II & III,--PRICE: Rs. 12-0-0=18s.] CONTENTS. VOLUME I Page. Page. Page. A-eng 1 A-lôn-gyi 8 Auk-kyin 29 Ah Hmun 2 A-Ma ib ib. A-hlè-ywa ib. Amarapura ib. Auk-myin ib. Ai-bur ib. 23 Auk-o-a-nauk 30 Ai-fang ib. Amarapura Myoma 24 Auk-o-a-she ib. Ai-ka ib. A-meik ib. Auk-sa-tha ib. Aik-gyi ib. A-mi-hkaw ib. Auk-seik ib. Ai-la ib. A-myauk-bôn-o ib. Auk-taung ib. Aing-daing ib. A-myin ib. Auk-ye-dwin ib. Aing-daung ib. Anauk-dônma 25 Auk-yo ib. Aing-gaing 3 A-nauk-gôn ib. Aung ib. Aing-gyi ib. A-nsuk-ka-byu ib. Aung-ban-chaung ib. -- ib. A-nauk-kaing ib. Aung-bin-le ib. Aing-ma ib. A-nauk-kyat-o ib. Aung-bôn ib. -- ib. A-nauk-let-tha-ma ib. Aung-ga-lein-kan ib. -- ib. A-nauk-pet ib. Aung-kè-zin ib. -- ib. A-nauk-su ib. Aung-tha 31 -- ib ib ib. Aing-she ib. A-nauk-taw ib ib. Aing-tha ib ib ib. Aing-ya ib. A-nauk-yat ib. -

Myanmar Child-Centred Risk Assessment

MYANMAR CHILD-CENTRED RISK ASSESSMENT ©UNICEF Myanmar/2013/Kyaw Kyaw Winn Second Edition 2017 Table of Contents FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................................. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................... 4 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................. 5 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT ................................................................................................................... 6 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Disaster Risk Reduction ....................................................................................................................... 8 The Case for Putting Children at the Centre of the Risk Equation ...................................................... 8 UNICEF and DRR in Myanmar 2017 .................................................................................................... 9 Disaster Risk in Myanmar .................................................................................................................... 9 CHILD-CENTRED RISK ASSESSMENT ...................................................................................................... 10 Advancements in the Second