Environmental Impact Assessment Addendum No 2 Appendices 21-25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

THE J OURNAL OF CARIBBEAN ORNITHOLOGY SOCIETY FOR THE C ONSERVATION AND S TUDY OF C ARIBBEAN B IRDS S OCIEDAD PARA LA C ONSERVACIÓN Y E STUDIO DE LAS A VES C ARIBEÑAS ASSOCIATION POUR LA C ONSERVATION ET L’ E TUDE DES O ISEAUX DE LA C ARAÏBE 2005 Vol. 18, No. 1 (ISSN 1527-7151) Formerly EL P ITIRRE CONTENTS RECUPERACIÓN DE A VES M IGRATORIAS N EÁRTICAS DEL O RDEN A NSERIFORMES EN C UBA . Pedro Blanco y Bárbara Sánchez ………………....................................................................................................................................................... 1 INVENTARIO DE LA A VIFAUNA DE T OPES DE C OLLANTES , S ANCTI S PÍRITUS , C UBA . Bárbara Sánchez ……..................... 7 NUEVO R EGISTRO Y C OMENTARIOS A DICIONALES S OBRE LA A VOCETA ( RECURVIROSTRA AMERICANA ) EN C UBA . Omar Labrada, Pedro Blanco, Elizabet S. Delgado, y Jarreton P. Rivero............................................................................... 13 AVES DE C AYO C ARENAS , C IÉNAGA DE B IRAMA , C UBA . Omar Labrada y Gabriel Cisneros ……………........................ 16 FORAGING B EHAVIOR OF T WO T YRANT F LYCATCHERS IN T RINIDAD : THE G REAT K ISKADEE ( PITANGUS SULPHURATUS ) AND T ROPICAL K INGBIRD ( TYRANNUS MELANCHOLICUS ). Nadira Mathura, Shawn O´Garro, Diane Thompson, Floyd E. Hayes, and Urmila S. Nandy........................................................................................................................................ 18 APPARENT N ESTING OF S OUTHERN L APWING ON A RUBA . Steven G. Mlodinow................................................................ -

Acoustic Communication in the Nocturnal Lepidoptera

Chapter 6 Acoustic Communication in the Nocturnal Lepidoptera Michael D. Greenfield Abstract Pair formation in moths typically involves pheromones, but some pyra- loid and noctuoid species use sound in mating communication. The signals are generally ultrasound, broadcast by males, and function in courtship. Long-range advertisement songs also occur which exhibit high convergence with commu- nication in other acoustic species such as orthopterans and anurans. Tympanal hearing with sensitivity to ultrasound in the context of bat avoidance behavior is widespread in the Lepidoptera, and phylogenetic inference indicates that such perception preceded the evolution of song. This sequence suggests that male song originated via the sensory bias mechanism, but the trajectory by which ances- tral defensive behavior in females—negative responses to bat echolocation sig- nals—may have evolved toward positive responses to male song remains unclear. Analyses of various species offer some insight to this improbable transition, and to the general process by which signals may evolve via the sensory bias mechanism. 6.1 Introduction The acoustic world of Lepidoptera remained for humans largely unknown, and this for good reason: It takes place mostly in the middle- to high-ultrasound fre- quency range, well beyond our sensitivity range. Thus, the discovery and detailed study of acoustically communicating moths came about only with the use of electronic instruments sensitive to these sound frequencies. Such equipment was invented following the 1930s, and instruments that could be readily applied in the field were only available since the 1980s. But the application of such equipment M. D. Greenfield (*) Institut de recherche sur la biologie de l’insecte (IRBI), CNRS UMR 7261, Parc de Grandmont, Université François Rabelais de Tours, 37200 Tours, France e-mail: [email protected] B. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Moth Hearing and Sound Communication

J Comp Physiol A (2015) 201:111–121 DOI 10.1007/s00359-014-0945-8 REVIEW Moth hearing and sound communication Ryo Nakano · Takuma Takanashi · Annemarie Surlykke Received: 17 July 2014 / Revised: 13 September 2014 / Accepted: 15 September 2014 / Published online: 27 September 2014 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Abstract Active echolocation enables bats to orient notion of moths predominantly being silent. Sexual sound and hunt the night sky for insects. As a counter-measure communication in moths may apply to many eared moths, against the severe predation pressure many nocturnal perhaps even a majority. The low intensities and high fre- insects have evolved ears sensitive to ultrasonic bat calls. quencies explain that this was overlooked, revealing a bias In moths bat-detection was the principal purpose of hear- towards what humans can sense, when studying (acoustic) ing, as evidenced by comparable hearing physiology with communication in animals. best sensitivity in the bat echolocation range, 20–60 kHz, across moths in spite of diverse ear morphology. Some Keywords Co-evolution · Sensory exploitation · eared moths subsequently developed sound-producing Ultrasound · Echolocating bats · Predator-prey organs to warn/startle/jam attacking bats and/or to com- municate intraspecifically with sound. Not only the sounds for interaction with bats, but also mating signals are within Introduction the frequency range where bats echolocate, indicating that sound communication developed after hearing by “sensory Insect hearing and sound communication is a fascinating exploitation”. Recent findings on moth sound communica- subject, where the combination of many classical studies tion reveal that close-range (~ a few cm) communication and recent progress using new technological and molecular with low-intensity ultrasounds “whispered” by males dur- methods provide an unsurpassed system for studying and ing courtship is not uncommon, contrary to the general understanding the evolution of acoustic communication, intraspecific as well as between predator and prey. -

China Birding Report Template

Jamaica 14-16 January 2010 Björn Anderson General I birded on Jamaica for 2.5 days only with the intention of bagging as many endemics as possible. It was highly successful, as I managed to get good views of all but one of the specialties. For some reasons the Jamaican Mango eluded me completely, as it was not recently present at the target site. The arrangements were made by Ann Sutton (resident bird guide), who also accompanied me in the field. The highlights of the trip were the good views of difficult birds such as Yellow-shouldered Grassquit and Jamaican Blackbird, but of course also the stunning Crested Quail-Dove, Streamertails, Amazona parrots and Jamaican Owl. I also completed the Tody family, birds that are amazingly cool guys. Itinerary 14/1 Ann picked me up at 6.00 at my hotel in Kingston and within an hour we were birding at Hardwar Gap on a winding road high above Kingston. The lifers came thick and fast and we had good views of Ring-tailed Pigeon, several Crested Quail-Doves, Arrow-headed Warblers. The trickiest of the endemics eluded us and we only heard it briefly. The forest was surprisingly quiet and shortly after midday we left the area for a long drive via Kingston around the eastern coast to Port Antonio on northeastern Jamaica. A short stop at some beautiful cliffs did not produce any White-tailed Tropicbird during a two minutes stop. In Port Antonio we checked in at a hotel east of town and went for an excellent dinner in the harbor of Port Antonio. -

BUTTERFLY and MOTH (DK Eyewitness Books)

EYEWITNESS Eyewitness BUTTERFLY & MOTH BUTTERFLY & MOTH Eyewitness Butterfly & Moth Pyralid moth, Margaronia Smaller Wood Nymph butterfly, quadrimaculata ldeopsis gaura (China) (Indonesia) White satin moth caterpillar, Leucoma salicis (Europe & Asia) Noctuid moth, Eyed Hawkmoth Diphthera caterpillar, hieroglyphica Smerinthus ocellata (Central (Europe & Asia) America) Madagascan Moon Moth, Argema mittrei (Madagascar) Thyridid moth, Rhondoneura limatula (Madagascar) Red Glider butterfly, Cymothoe coccinata (Africa) Lasiocampid moth, Gloveria gargemella (North America) Tailed jay butterfly, Graphium agamemnon, (Asia & Australia) Jersey Tiger moth, Euplagia quadripunctaria (Europe & Asia) Arctiid moth, Composia credula (North & South America) Noctuid moth, Noctuid moth, Mazuca strigitincta Apsarasa radians (Africa) (India & Indonesia) Eyewitness Butterfly & Moth Written by PAUL WHALLEY Tiger Pierid butterfly, Birdwing butterfly, Dismorphia Troides hypolitus amphione (Indonesia) (Central & South America) Noctuid moth, Baorisa hieroglyphica (India & Southeast Asia) Hairstreak butterfly, Kentish Glory moth, Theritas coronata Endromis versicolora (South America) (Europe) DK Publishing, Inc. Peacock butterfly, Inachis io (Europe and Asia) LONDON, NEW YORK, MELBOURNE, MUNICH, and DELHI Project editor Michele Byam Managing art editor Jane Owen Special photography Colin Keates (Natural History Museum, London), Kim Taylor, and Dave King Editorial consultants Paul Whalley and the staff of the Natural History Museum Swallowtail butterfly This Eyewitness -

Proceedings of the Forteenth Symposium on the Natural History of the Bahamas

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FORTEENTH SYMPOSIUM ON THE NATURAL HISTORY OF THE BAHAMAS Edited by Craig Tepper and Ronald Shaklee Conference Organizer Thomas Rothfus Gerace Research Centre San Salvador Bahamas 2011 Cover photograph – “Iggie the Rock Iguana” courtesy of Ric Schumacher Copyright Gerace Research Centre All Rights Reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or information storage or retrieval system without permission in written form. Printed at the Gerace Research Centre ISBN 0-935909-95-8 The 14th Symposium on the Natural History of the Bahamas VISITORS TO RAM’S HORN, PITHECELLOBIUM KEYENSE BRITT. EX BRITT. AND ROSE, ON SAN SALVADOR ISLAND, THE BAHAMAS Nancy B. Elliott1, Carol L. Landry2, Lee B. Kass3, and Beverly J. Rathcke4 1Department of Biology Siena College Loudonville, NY 11211 2Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology The Ohio State University Mansfield, OH 44906 3The L. H. Bailey Hortorium, Department of Plant Biology Cornell University Ithaca, NY 14953 4Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI 48109 ABSTRACT and the pierid Phoebis agarithe were seen more than once. One dipteran, Callitrega macellaria, We made observations on individuals of and two nectivorous birds, the bananaquit, Pithecellobium keyense (ram’s horn) in flower on Coereba flaveola, and the Bahama woodstar, San Salvador during the following periods: late Calliphlox evelynae, were occasional visitors. December 2002 to early January 2003, October 2007 and December 2010. Most of the visitors we INTRODUCTION saw belonged to the insect orders Hymenoptera and Lepidoptera. -

Field Guide Invasives Pests in Caribbean Ukots Part 1

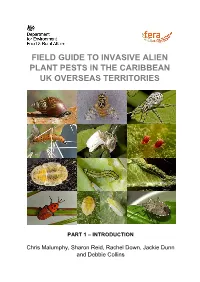

FIELD GUIDE TO INVASIVE ALIEN PLANT PESTS IN THE CARIBBEAN UK OVERSEAS TERRITORIES PART 1 – INTRODUCTION Chris Malumphy, Sharon Reid, Rachel Down, Jackie Dunn and Debbie Collins UKOT Caribbean Invasive Plant Pest Field Guide FIELD GUIDE TO INVASIVE ALIEN PLANT PESTS IN THE CARIBBEAN UK OVERSEAS TERRITORIES Part 1 Introduction Chris Malumphy, Sharon Reid, Rachel Down, Jackie Dunn and Debbie Collins Second Edition Fera Science Ltd., National Agri-food Innovation Campus, Sand Hutton, York, YO41 1LZ, United Kingdom https://fera.co.uk/ Published digitally: April 2018. Second edition published digitally: April 2019. Divided into 6 parts to enable easier download © Crown copyright 2018-19 Suggested citation: Malumphy, C., Reid, S., Down, R., Dunn., J. & Collins, D. 2019. Field Guide to Invasive Alien Plant Pests in the Caribbean UK Overseas Territories. 2nd Edition. Part 1 – Introduction. Defra/Fera. 30 pp. Frontispiece Top row: Giant African land snail Lissachatina fulica © C. Malumphy; Mediterranean fruit fly Ceratitis capitata © Crown copyright; Sri Lankan weevil, Myllocerus undecimpustulatus undatus adult © Gary R. McClellan. Second row: Cactus moth Cactoblastis cactorum caterpillar © C. Malumphy; Cottony cushion scale Icerya purcashi © Crown copyright; Red palm mite Raoiella indica adults © USDA. Third row: Tomato potato psyllid Bactericera cockerelli © Fera; Cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera © Crown copyright; Croton scale Phalacrococcus howertoni © C. Malumphy. Bottom row: Red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus © Fera; Tobacco whitefly -

Curry Hammock State Park 2016

Curry Hammock State Park APPROVED Unit Management Plan STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Division of Recreation and Parks December 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PARK ....................................... 1 Park Significance ................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE PLAN..................................................... 2 MANAGEMENT PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................... 7 Management Authority and Responsibility .............................................. 7 Park Management Goals ...................................................................... 8 Management Coordination ................................................................... 9 Public Participation ..............................................................................9 Other Designations .............................................................................9 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT COMPONENT INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 11 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT..................................... 12 Natural Resources ............................................................................. 12 Topography .................................................................................. 12 Geology ...................................................................................... -

Empyreuma Species and Species Limits: Evidence from Morphology and Molecules (Arctiidae: Arctiinae: Ctenuchini)

iuumal of the Lepidopterists' Society ,58 (1), 2004, 21-32 EMPYREUMA SPECIES AND SPECIES LIMITS: EVIDENCE FROM MORPHOLOGY AND MOLECULES (ARCTIIDAE: ARCTIINAE: CTENUCHINI) SUSAN J, WELLER,l REBECCA B, SIMMONS2 AND ANDERS L. CARLSON3 ABSTRACT. Species limits within Empyreurrw are addressed using a morphological study of male and female genitalia and sequence data from the mitodlOndrial gene COl. Currently, four species are recognized: E. pugione (L.), E, affinis Rothschild, E, heros Bates, E, anassa Forbes, Two cntities can be readily distinguished, the Jamaican E. anassa and a widespread E. pugione-complex, based on adult morphology. Neither E. affinis nor E, heros can be distingUished by coloration or genitalic differences, Analysis of COl haplotypes suggests that E, affinis is not genetically distinct from E. pugione « 1% sequence divergence); however, the population from the Bahamas, E, heros, is differentiated from other haplotypes with an uncorrected sequence divergence of 5%. We place E. affinis Rothschild, 1912 as a new synonym of E. pugione Hubner 1818, and recognize three spedes: E. anassa, E. pugione, and E. heros. This paper includes a revised synonymic checklist of species and a redescription of the genus, with notes on biology, and with illustrations of male genitalia, female genitalia, wing venation, and abdominal sclerites. Additional key words: Caribbean fauna, Greater Antilles, mimicry, phylogeography, systematics. The tiger moth genus Empyreuma Hubner (Arcti affinis as a junior synonym of E. pugione. Bates (1934) idae: Arctiinae: Ctenuchini) (Hubner 1818) is endemic subsequently described E. heros from the Bahamas, but to the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean, and has ex he did not provide figures or diagnostiC features that panded its distribution into Florida (Adam & Goss separate it from previously described species. -

Research Article Immature Stages and Life Cycle of the Wasp Moth, Cosmosoma Auge (Lepidoptera: Erebidae: Arctiinae) Under Laboratory Conditions

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Psyche Volume 2014, Article ID 328030, 6 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/328030 Research Article Immature Stages and Life Cycle of the Wasp Moth, Cosmosoma auge (Lepidoptera: Erebidae: Arctiinae) under Laboratory Conditions Gunnary León-Finalé and Alejandro Barro Department of Animal and Human Biology, Faculty of Biology, University of Havana, Calle 25 No. 455 Entre I y J, Vedado, Municipio Plaza, 10400 Ciudad de la Habana, Cuba Correspondence should be addressed to Alejandro Barro; [email protected] Received 24 February 2014; Revised 20 May 2014; Accepted 29 May 2014; Published 9 July 2014 Academic Editor: Kent S. Shelby Copyright © 2014 G. Leon-Final´ e´ and A. Barro. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Cosmosoma auge (Linnaeus 1767) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) is a Neotropical arctiid moth common in Cuban mountainous areas; however, its life cycle remains unknown. In this work, C. auge life cycle is described for the first time; also, immature stages are describedusingaCubanpopulation.LarvaewereobtainedfromgravidwildfemalescaughtinVinales˜ National Park and were fed with fresh leaves of its host plant, the climbing hempweed Mikania micrantha Kunth (Asterales: Asteraceae), which is a new host plant record. Eggs are hemispherical and hatching occurred five days after laying. Larval period had six instars and lasted between 20 and 22 days. First and last larval stages are easily distinguishable from others. First stage has body covered by chalazae and last stage has body covered by verrucae as other stages but has a tuft on each side of A1 and A7. -

Little Cayman Insect Fauna

10. THE INSECT FAUNA OF LITTLE CAYMAN R.R. Askew Little Cayman is seldom mentioneZ in entoiiiologicali. literature. The 1938 Oxford University Biological Expedition spent thirteen days or, the islanc? and reports on the resultinq collection deal with Odona-ta (Fraser, 19431, wa-ter-bugs (Hulgerforc?, 1940), Nemoptera (Banks, 1941) , cicadas (Davis, 19391 , Carabidae (Darlington, 194'73 , Cerambycidae (Fisher, 1941, 1948) , butterflies (Carpenter & Lewis, 1943) and Sphingidae (Jordan, 1940j , During the 19'75 expedition, insects of all orders were studied over a period of about five weeks and many additions will eventually be made to the island's species list. At present, however, identification of the insects collected has, with the exception of the butterflies which have been considered separately, proceeded in the majority of cases only as far as the family level. Application of family names for the most part follows Borror & DeLong (1966). In this paper the general characteristics of the insect fauna are described. Collecting Methods A, General collecting with sweep-net, pond-net, butterfly net and searching foliage, tree trunks and on the ground. A cone-net attached to a vehicle was used on one occasion. Also considered as being caught by 'general collecting' are insects found resting on walls adjacent to outside electric lights at Pirates' Point. B. A Malaise trap (Model 300 Health-EE-X supplied by Entomology Research Institute, Minnesota) was erected on 17th July and operated almost continuously to the end of the expedition. It was situated at Pirate's Point, just south of the lagoon and road, in a glade between bushes of Conocarpus and other shrubs growing at the base of the northern face of the beach ridge.