Scotch Whisky: History, Heritage and the Stock Cycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Single Malt Scotch Whisky Irish Whiskey Bourbon

SINGLE MALT SCOTCH WHISKY RYE WHISKEY Ardbeg 10 Year 10.25 (Ri) 1mit 8.50 Balvenie 12 Year Doublewood 11 Bulleit 7.75 Caol Ila 12 Year 11 Knob Creek 9.25 Cragganmore 12 Year 10.75 Old Overholt 6.25 Glenfiddich 12 Year 9.75 Sazerac 8 Glenlivet 12 Year 9.75 Glenmorangie 10 Year 10 Highland Park 12 Year 10.75 McMENAMINS WHISKEY Lagavulin 16 Year 14.25 Laphroaig 10 Year 9.75 Aval Pota 7 Oban 14 Year 13.25 Billy 7.50 Talisker 10 Year 11.25 Hogshead 7.75 The Macallan 12 Year 11 Monkey Puzzle 6.50 White Owl 6.50 IRISH WHISKEY Bushmills 7.50 TENNESSEE WHISK(E)Y Bushmills 10 Year Single Malt 9.75 Bushmills 16 Year 12 Gentleman Jack 7.75 Bushmills Black Bush 8.50 George Dickel 9 Year Hand Select 10 Jameson 7.75 Jack Daniel’s #7 Black Label 6.75 Jameson 12 Year 13.75 Jameson 18 Year 20.25 Jameson Black 8.50 JAPANESE WHISKY Redbreast 12 Year 13.75 Redbreast 15 Year 15.75 Hakushu 12 Year 12.75 Tullamore Dew 7.75 Suntory Hibiki 12 Year 13.25 The Yamazaki 12 Year 13.25 BOURBON WHISK(E)Y The Yamazaki 18 Year 30 Baker’s 7 Year 10.75 Basil Hayden’s 10 Booker’s 11.25 CANADIAN WHISKY Buffalo Trace 6.50 Crown Royal 7.75 Bulleit 7.75 Pendleton 1910 9.25 Bulleit 10 Year 9.25 Pendleton 7.25 Eagle Rare 10 Year 7.75 Yukon Jack 6.25 Four Roses Small Batch 9.25 George T. -

Whisky Bible

WHISKY BIBLE FOURTH EDITION aqua vitae uisge beatha – ‘water of life’ A brief history of Whisky The Gaelic ‘usquebaugh’, meaning ‘Water of Life’, phonetically became ‘usky’ and then ‘whisky’ in English. Scotland has internationally protected the term ‘Scotch’. For a whisky to be labelled Scotch it has to be produced in Scotland. ‘Eight bolls of malt to Friar John Cor wherewith to make aqua vitae’. The entry above appeared in the Exchequer Rolls as long ago as 1494 and appears to be the earliest documented record of distilling in Scotland. This was sufficient to produce almost 1500 bottles. Legend would have it that St Patrick introduced distilling to Ireland in the fifth century AD and that the secrets travelled with the Dalriadic Scots when they arrived in Kintyre around AD500. The spirit was universally termed aqua vitae (‘water of life’) and was commonly made in monasteries, and chiefly used for medicinal purposes, being prescribed for the preservation of health, the prolongation of life, and for the relief of colic, palsy and even smallpox. Scotland’s great Renaissance king, James IV (1488-1513) was fond of ‘ardent spirits’. When the king visited Dundee in 1506, the treasury accounts record a payment to the local barber for a supply of aqua vitae for the king’s pleasure. The reference to the barber is not surprising. In 1505, the Guild of Surgeon Barbers in Edinburgh was granted a monopoly over the manufacture of aqua vitae – a fact that reflects the spirits perceived medicinal properties as well as the medicinal talents of the barbers. -

Lactic Acid Bacteria – the Uninvited but Generally Welcome Participants In

Lactic acid bacteria – the uninvited (a) but generally welcome participants in malt whisky fermentation Fergus G. Priest Coffey still. Like malt diversity resulting in Lactobacillus fermentum and LEFT: (b) whisky, it must be matured Lactobacillus paracasei as commonly dominant species by Fig. 1. Fluorescence photomicrographs of whisky for a minimum of 3 years. about 40 hours. During the final stages when the yeast is fermentation samples; green cells Grain whisky is the base of dying, a homofermentative bacterium related to Lacto- are viable, red cells are dead. (a) the standard blends such as bacillus acidophilus often proliferates and produces large Wort on entering the washback, (b) Famous Grouse, Teachers, amounts of lactic acid. after fermentation for 55 hours and and Johnnie Walker which (c) after fermentation for 95 hours. (a) AND (b) ARE REPRODUCED will contain between 15 Effects of lactobacilli on the flavour of malt WITH PERMISSION FROM VAN BEEK & and 30 % malt whisky. whisky PRIEST (2002, APPL ENVIRON Both products use a The bacteria can affect the flavour of the spirit in two MICROBIOL 68, 297–305); (c) COURTESY F. G. PRIEST similar process, but here ways. First, they will reduce the pH of the fermentation we will focus on malt (c) through the production of acetic and lactic acids. This whisky. Malted barley is will lead to a general increase in esters following milled, infused in water at distillation, a positive feature that has traditionally been about 64 °C for some 30 associated with the late lactic fermentation. This general minutes to 1 hour and the effect is apparent in the data presented in Fig. -

Boisdale of Bishopsgate Whisky Bible

BOISDALE Boisdale of Bishopsgate Whisky Bible 1 All spirits are sold in measures of 25ml or multiples thereof. All prices listed are for a large measure of 50ml. Should you require a 25ml measure, please ask. All whiskies are subject to availability. 1. Springbank 10yr 19. Old Pulteney 17yr 37. Ardbeg Corryvreckan 55. Glenfiddich 21yr 2. Highland Park 12yr 20. Glendronach 12yr 38. Ardbeg 10yr 56. Glenfiddich 18yr 3. Bowmore 12yr 21. Whyte & Mackay 30yr 39. Lagavulin 16yr 57. Glenfiddich 15yr Solera 4. Oban 14yr 22. Royal Lochnagar 12yr 40. Laphroaig Quarter Cask 58. Glenfarclas 10yr 5. Balvenie 21yr PortWood 23. Talisker 10yr 41. Laphroaig 10yr 59. Macallan 18yr 6. Glenmorangie Signet 24. Springbank 15yr 42. Ardbeg Uigeadail 60. Highland Park 18yr 7. Suntory Yamazaki DR 25. Ailsa Bay 43. Tomintoul 16yr 61. Glenfarclas 25yr 8. Cragganmore 12yr 26. Caol Ila 12yr 44. Glenesk 1984 62. Macallan 10yr Sherry Oak 9. Brora 30yr 27. Port Charlotte 2008 45. Glenmorangie 25yr QC 63. Glendronach 12yr 10. Clynelish 14yr 28. Balvenie 15yr 46. Strathmill 12yr 64. Balvenie 12yr DoubleWood 11. Isle of Jura 10yr 29. Glenmorangie 18yr 47. Glenlivet 21yr 65. Aberlour 18yr 12. Tobermory 10yr 30. Macallan 12yr Sherry Cask 48. Macallan 12yr Fine Oak 66. Auchentoshan 3 Wood 13. Glenfiddich 26yr Excellence 31. Bruichladdie Classic Laddie 49. Glenfiddich 12yr 67. Dalmore King Alexander III 14. Dalwhinnie 15yr 32. Chivas Regal 18yr 50. Monkey Shoulder 68. Auchentoshan 12yr 15. Glenmorangie Original 33. Chivas Regal 25yr 51. Glenlivet 25yr 69. Benrinnes 23yr 2 16. Bunnahabhain 12yr 34. Dalmore Cigar Malt 52. Glenlivet 12yr 70. -

9913 2004 Cover Outer

Diageo Annual Report 2004 Annual Report 2004 Diageo plc 8 Henrietta Place London W1G 0NB United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 20 7927 5200 Fax +44 (0) 20 7927 4600 www.diageo.com Registered in England No. 23307 Diageo is... © 2004 Diageo plc.All rights reserved. All brands mentioned in this Annual Report are trademarks and are registered and/or otherwise protected in accordance with applicable law. delivering results 165 Diageo Annual Report 2004 Contents Glossary of terms and US equivalents 1Highlights 63 Directors and senior management In this document the following words and expressions shall, unless the context otherwise requires, have the following meanings: 2Chairman’s statement 66 Directors’ remuneration report 3Chief executive’s review 77 Corporate governance report Term used in UK annual report US equivalent or definition Acquisition accounting Purchase accounting 5Five year information 83 Directors’ report Associates Entities accounted for under the equity method American Depositary Receipt (ADR) Receipt evidencing ownership of an ADS 10 Business description 84 Consolidated financial statements American Depositary Share (ADS) Registered negotiable security, listed on the New York Stock Exchange, representing four Diageo plc ordinary shares of 28101⁄108 pence each 10 – Overview 85 – Independent auditor’s report to Called up share capital Common stock 10 – Strategy the members of Diageo plc Capital allowances Tax depreciation 10 – Premium drinks 86 – Consolidated profit and loss account Capital redemption reserve Other additional capital -

Alcohol Units a Brief Guide

Alcohol Units A brief guide 1 2 Alcohol Units – A brief guide Units of alcohol explained As typical glass sizes have grown and For example, most whisky has an ABV of 40%. popular drinks have increased in A 1 litre (1,000ml) bottle of this whisky therefore strength over the years, the old rule contains 400ml of pure alcohol. This is 40 units (as 10ml of pure alcohol = one unit). So, in of thumb that a glass of wine was 100ml of the whisky, there would be 4 units. about 1 unit has become out of date. And hence, a 25ml single measure of whisky Nowadays, a large glass of wine might would contain 1 unit. well contain 3 units or more – about the The maths is straightforward. To calculate units, same amount as a treble vodka. take the quantity in millilitres, multiply it by the ABV (expressed as a percentage) and divide So how do you know how much is in by 1,000. your drink? In the example of a glass of whisky (above) the A UK unit is 10 millilitres (8 grams) of pure calculation would be: alcohol. It’s actually the amount of alcohol that 25ml x 40% = 1 unit. an average healthy adult body can break down 1,000 in about an hour. So, if you drink 10ml of pure alcohol, 60 minutes later there should be virtually Or, for a 250ml glass of wine with ABV 12%, none left in your bloodstream. You could still be the number of units is: suffering some of the effects the alcohol has had 250ml x 12% = 3 units. -

Spirits, Bottled Wine & Fossils

Our complete Treasure List of SPIRITS, BOTTLED WINE & FOSSILS Each the result of human curiosity and discovery. 1 FROM CURIOSITY, DISCOVERY EVOLVES. Humans have long tried to understand our world, explaining its complexities through theories of spirituality, biology, geography and astronomy. This insatiable thirst for understanding fuelled a period of unprecedented discovery during the 1800s with the mapping of our globe, the industrial revolution and the collection of countless botanical, zoological and geological artefacts. Our minds expanded with curiosity as mysterious fossils were uncovered; answering some questions, but presenting thousands more. And just as palaeontologists have captured our imagination with incredible beasts from centuries past, so too have the world’s master distillers by hand-crafting the finest spirits through alchemy of earth’s elements. These spirits endeavour to explain the complexities of our world and are celebrated, wholeheartedly, at Evolve Spirits Bar. 2 SPIRITS & WINE Tasmanian Vodka & Gin 82 – 87 Vodka & Gin 88 – 93 Whisk(e)y Tasmanian 4 – 12 Australia (Mainland) 13 – 14 Scottish 15 Blends, Vatted, Fusion 16 – 17 Lowlands 18 Speyside 19 – 29 Highland 30 – 34 Campbeltown 35 – 36 Islands 37 - 38 Islay 39 – 46 Irish 47 – 49 Japanese 50 – 53 American 54 – 59 World 60 – 62 Cognac, Armagnac & Brandies 63 – 69 Rum, Ron & Rhum 70 – 76 Tequila, Mezcal & Sotol 77 – 81 Wine by the Bottle FOSSILS 94 3 Tasmanian Whisky Tasmania is ideally situated to make malt whisky, and yet 150 years after the last licensed Tasmanian distillery closed its doors, it took a whisky lover to realise the environment was perfect. Bill Lark, owner and founder of Lark Distillery and renowned godfather of Australian whisky realised that that everything you need for a world-class whisky was in Tasmania: rich fields of barley, an abundance of wonderfully pure soft water, highland peat bogs and the perfect climate to bring all the ingredients together in a marriage of science, art and passion. -

Auction Two 2020

AUCTION TWO 2020 Closing Date: Sunday 16th August 2020. Final bids accepted up to midday on the closing date. Send your bid sheets to: Dave Allen, 11 Beechwood Gardens, Mossend, North Lanarkshire ML4 2PF, Scotland. Tel : 01698-333495. E-mail : [email protected] When paying by cheque, please make payment to: “The Mini Bottle Club” When paying by PayPal please send payment to: [email protected] 1 2 500 yrs. 1494 - 1994 Central Tablers Lost Legends No. 25 of 500 No. 135 of 500 Meeting - Stirling Whisky Connoisseur 1. Linlithgow 26yo 2. Allt A Bhainne 3. Bunnahabhain 4. Knockando 1986 5. Tullibardine SLMSW 12yo SHM 25yo SIMW PSMSW HSMSW Distilled 1975 5cl 43%vol Dist. 30/11/94 Bot. Feb. 90 Bottled 1998 5cl 40%vol 5cl 59.3%vol Stillman Selection 5cl 46%vol 5cle 40%vol 50mle 40%alc/vol 6. Glenlivet Founder’s Reserve 7. Glenlivet 12yo 8. Glenlivet 15yo 9. Glenlivet 15yo 10. Glenlivet 18yo SMSW UAMSW SMSW SMSW SMSW 5cl/50mle ⅒ pint 86ºProof 5cl/50mle 5cl/50mle 50ml 43%alc/vol 40%vol/40%alc/vol/40ºGL US Import 40%vol/40ºGL/40%alc/vol 40%vol/40ºGL/40%alc/vol Japanese import 11. Glenrothes 8yo 12. Glenturret 1997 13. Highland Park 8yo 14. Macallan 1990 SSMSW HSMSW OSMSW SSMSW 5cl 40%vol 5cl 40%vol 5cl 43%vol 40%vol 5cl 3 15. Ardbeg 16yo 16. Bowmore 14yo 17. Bowmore 17yo 18. Bruichladdich 19yo 19. Bruichladdich 21yo SMSW SMSW SMSW SMSW SMSW 5cl 55.6%vol 5cl 56.7%vol 5cl 54.8%vol 5cl 51.2%vol 5cl 52.1%vol 20. -

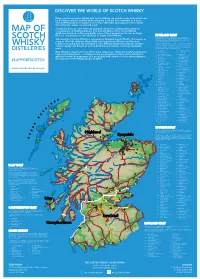

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages

The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages © 2016 Robert A. Freitas Jr. All Rights Reserved. Abstract. Specialized nanofactories will be able to manufacture specific products or classes of products very efficiently and inexpensively. This paper is the first serious scaling study of a nanofactory designed for the manufacture of a specific food product, in this case high-value-per- liter alcoholic beverages. The analysis indicates that a 6-kg desktop appliance called the Fine Spirits Synthesizer, aka. the “Whiskey Machine,” consuming 300 W of power for all atomically precise mechanosynthesis operations, along with a commercially available 59-kg 900 W cryogenic refrigerator, could produce one 750 ml bottle per hour of any fine spirit beverage for which the molecular recipe is precisely known at a manufacturing cost of about $0.36 per bottle, assuming no reduction in the current $0.07/kWh cost for industrial electricity. The appliance’s carbon footprint is a minuscule 0.3 gm CO2 emitted per bottle, more than 1000 times smaller than the 460 gm CO2 per bottle carbon footprint of conventional distillery operations today. The same desktop appliance can intake a tiny physical sample of any fine spirit beverage and produce a complete molecular recipe for that product in ~17 minutes of run time, consuming <25 W of power, at negligible additional cost. Cite as: Robert A. Freitas Jr., “The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages,” IMM Report No. 47, May 2016; http://www.imm.org/Reports/rep047.pdf. 2 Table of Contents 1. -

Speyside the Land of Whisky

The Land of Whisky A visitor guide to one of Scotland’s five whisky regions. Speyside Whisky The practice of distilling whisky No two are the same; each has has been lovingly perfected its own proud heritage, unique throughout Scotland for centuries setting and its own way of doing and began as a way of turning things that has evolved and been rain-soaked barley into a drinkable refined over time. Paying a visit to spirit, using the fresh water from a distillery lets you discover more Scotland’s crystal-clear springs, about the environment and the streams and burns. people who shape the taste of the Scotch whisky you enjoy. So, when To this day, distilleries across the you’re sitting back and relaxing country continue the tradition of with a dram of our most famous using pure spring water from the export at the end of your distillery same sources that have been tour, you’ll be appreciating the used for centuries. essence of Scotland as it swirls in your glass. From the source of the water and the shape of the still to the Home to the greatest wood of the cask used to mature concentration of distilleries in the the spirit, there are many factors world, Scotland is divided into five that make Scotch whisky so distinct whisky regions. These are wonderfully different and varied Highland, Lowland, Speyside, Islay from distillery to distillery. and Campbeltown. Find out more information about whisky, how it’s made, what foods to pair it with and more: www.visitscotland.com/whisky For more information on travelling in Scotland: www.visitscotland.com/travel Search and book accommodation: www.visitscotland.com/accommodation 05 15 03 06 Speyside 07 04 08 16 01 Speyside is home to some of Speyside you’re never far from a 10 Scotland’s most beautiful scenery distillery or two. -

Letter from the President the Scotch-Irish Society of the United

OCIETY S O H F S I T R H I - E H NEWSLETTER Spring 2012 U C . T S O . A C . S The Scotch-Irish Society 1889 of the United States of America Letter from the President You would think that a celebration of our Scotch-Irish culture would be seen by all as a positive expression of a great American heritage, but not everyone speaks kindly of us. Kevin Myers, the renowned Irish columnist recently wrote “There's no end to this nonsense of subdividing society, defining The Hermitage – Nashville, Tennessee and redefining ‘identity’, or even worse, ‘culture’, like a coke-dealer fine-cutting a stash on a mirror. The outcome is a multiply-divided It has been a few years since I visited community, sects in the city, with almost everyone having their own The Hermitage , home of another mini-culture. Healthy societies don't dwell on identity.” Although Scotch-Irish “Jackson,” President Andrew specifically referring to Ulster-Scots and a new BBC documentary Jackson. (Last issue we highlighted the about their unique cuisine, his diatribe could just as easily be home of Stonewall Jackson in Lexington, applied to us. Comments from readers on the newspaper’s website Virginia.) I remember it being an easy day trip, just five miles from the Gaylord were virtually unanimous in taking Mr. Myers to task. Opryland Resort and Convention Center In 2010, Harvard Law professor Noah Feldman wrote of our where I was staying on business and only demise. "So, when discussing the white elite that exercised such twenty minutes from downtown Nashville.