A New Branch of Criticism for the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking Simulators As Response to the Problem of Optimization

The Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Copenhagen 2018 The Aesthetics of the Aesthetics of the Aesthetics of Video Games: Walking Simulators as Response to the problem of Optimization Jesper Juul: “The Aesthetics of the Aesthetics of the Aesthetics of Video Games: Walking Simulators as Response to the problem of Optimization”. 12th International Conference on the Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Copenhagen, August 13-15, 2018. www.jesperjuul.net/text/aesthetics3 Figure 1: Dear Esther (The Chinese Room 2012). Walking a linear path, listening to the narrator. Figure 2: Proteus (Key and Kanaga 2013). Exploring a pastoral and pixelated generated island with little challenge. 1 Figure 3: Gone Home (The Fullbright Company 2013). Returning to your childhood home to learn of your sister’s life through minimal puzzles. In games, we traditionally expect that the effort we exert will influence the game state and outcome, and we expect to feel emotionally attached to this outcome (Juul 2003) such that performing well will make us happy, and performing poorly will make us unhappy. But a number of recent games, derogatorily dismissed as walking simulators, limit both our options for interacting with the game world and our feeling of responsibility for the outcome. Examples include Dear Esther (The Chinese Room 2012), Proteus (Key & Kanaga 2013), and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (The Chinese Room 2015), and Gone Home (The Fullbright Company 2013). “Walking simulator” is a divisive term, originally coined to dismiss these experiences as “not real games” lacking gameplay, thus only simulating “walking”. Developers are divided over whether to reject (KILL SCREEN STAFF 2016) the term or reclaim (Butler 2015 p. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

Exploring the Experiences of Gamers Playing As Multiple First-Person Video Game Protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’S Single-Player Narrative

Exploring the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative Richard Alexander Meyers Bachelor of Arts Submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) School of Creative Practice Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2018 Keywords First-Person Shooter (FPS), Halo 3: ODST, Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), ludus, paidia, phenomenology, video games. i Abstract This thesis explores the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST, with a view to formulating an understanding of player experience for the benefit of video game theorists and industry developers. A significant number of contemporary console-based video games are coming to be characterised by multiple playable characters within a game’s narrative. The experience of playing as more than one video game character in a single narrative has been identified as an under-explored area in the academic literature to date. An empirical research study was conducted to explore the experiences of a small group of gamers playing through Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used as a methodology particularly suited to exploring a new or unexplored area of research and one which provides a nuanced understanding of a small number of people experiencing a phenomenon such as, in this case, playing a video game. Data were gathered from three participants through experience journals and subsequently through two semi- structured interviews. The findings in relation to participants’ experiences of Halo 3: ODST’s narrative were able to be categorised into three interrelated narrative elements: visual imagery and world-building, sound and music, and character. -

Investigating Meaning in Videogames

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Investigating Procedural Expression and Interpretation in Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1mn3x85g Author Treanor, Mike Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT SANTA CRUZ INVESTIGATING PROCEDURAL EXPRESSION AND INTERPRETATION IN VIDEOGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Mike Treanor June 2013 The Dissertation of Mike Treanor is approved: Professor Michael Mateas, Chair Professor Noah Wardrip-Fruin Professor Ian Bogost Rod Humble (CEO Linden Lab) Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures ........................................................................................................... vii Abstract…….. ............................................................................................................. x Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 Procedural Rhetoric ...................................................................................... 4 Critical Technical Practice ............................................................................ 7 Research -

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Journal of Games Is Here to Ask Himself, "What Design-Focused Pre- Hideo Kojima Need an Editor?" Inferiors

WE’RE PROB NVENING ABLY ALL A G AND CO BOUT V ONFERRIN IDEO GA BOUT C MES ALSO A JournalThe IDLE THUMBS of Games Ultraboost Ad Est’d. 2004 TOUCHING THE INDUSTRY IN A PROVOCATIVE PLACE FUN FACTOR Sessions of Interest Former developers Game Developers Confer We read the program. sue 3D Realms Did you? Probably not. Read this instead. Computer game entreprenuers claim by Steve Gaynor and Chris Remo Duke Nukem copyright Countdown to Tears (A history of tears?) infringement Evolving Game Design: Today and Tomorrow, Eastern and Western Game Design by Chris Remo Two founders of long-defunct Goichi Suda a.k.a. SUDA51 Fumito Ueda British computer game developer Notable Industry Figure Skewered in Print Crumpetsoft Disk Systems have Emil Pagliarulo Mark MacDonald sued 3D Realms, claiming the lat- ter's hit game series Duke Nukem Wednesday, 10:30am - 11:30am infringes copyright of Crumpetsoft's Room 132, North Hall vintage game character, The Duke of industry session deemed completely unnewswor- Newcolmbe. Overview: What are the most impor- The character's first adventure, tant recent trends in modern game Yuan-Hao Chiang The Duke of Newcolmbe Finds Himself design? Where are games headed in the thy, insightful next few years? Drawing on their own in a Bit of a Spot, was the Walton-on- experiences as leading names in game the-Naze-based studio's thirty-sev- design, the panel will discuss their an- enth game title. Released in 1986 for swers to these questions, and how they the Amstrad CPC 6128, it features see them affecting the industry both in Japan and the West. -

Sparking a Steam Revolution: Examining the Evolution and Impact of Digital Distribution in Gaming

Sparking a Steam Revolution: Examining the Evolution and Impact of Digital Distribution in Gaming by Robert C. Hoile At this moment there’s a Renaissance taking place in games, in the breadth of genres and the range of emotional territory they cover. I’d hate to see this wither on the vine because the cultural conversation never caught up to what was going on. We need to be able to talk about art games and ‘indie’ games the ways we do about art and indie film. (Isbister xvii) The thought of a videogame Renaissance, as suggested by Katherine Isbister, is both appealing and reasonable, yet she uses the term Renaissance rather casually in her introduction to How Games Move Us (2016). She is right to assert that there is diversity in the genres being covered and invented and to point out the effectiveness of games to reach substantive emotional levels in players. As a revival of something in the past, a Renaissance signifies change based on revision, revitalization, and rediscovery. For this term to apply to games then, there would need to be a radical change based not necessarily on rediscovery of, but inspired/incited by something perceived to be from a better time. In this regard the videogame industry shows signs of being in a Renaissance. Videogame developers have been attempting to innovate and push the industry forward for years, yet people still widely regard classics, like Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998), as the best games of all time. As with the infatuation with sequels in contemporary Hollywood cinema, game companies are often perceived as producing content only for the money while neglecting quality. -

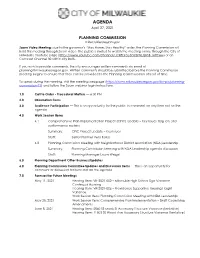

Planning Comission Packet 04.27.2021

AGENDA April 27, 2021 PLANNING COMMISSION milwaukieoregon.gov Zoom Video Meeting: due to the governor’s “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order, the Planning Commission will hold this meeting through Zoom video. The public is invited to watch the meeting online through the City of Milwaukie YouTube page (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCRFbfqe3OnDWLQKSB_m9cAw) or on Comcast Channel 30 within city limits. If you wish to provide comments, the city encourages written comments via email at [email protected]. Written comments should be submitted before the Planning Commission meeting begins to ensure that they can be provided to the Planning Commissioners ahead of time. To speak during the meeting, visit the meeting webpage (https://www.milwaukieoregon.gov/bc-pc/planning- commission-71) and follow the Zoom webinar login instructions. 1.0 Call to Order - Procedural Matters — 6:30 PM 2.0 Information Items 3.0 Audience Participation — This is an opportunity for the public to comment on any item not on the agenda 4.0 Work Session Items 4.1 Comprehensive Plan Implementation Project (CPIC) Update – Key Issues: flag lots and performance metrics Summary: CPIC Project Update – Key Issues Staff: Senior Planner Vera Kolias 4.2 Planning Commission Meeting with Neighborhood District Association (NDA)Leadership Summary: Planning Commission Meeting with NDA Leadership agenda discussion Staff: Planning Manager Laura Weigel 5.0 Planning Department Other Business/Updates 6.0 Planning Commission Committee Updates and Discussion Items — This is an opportunity -

Firewatch Download Torrent Mac the Forest Free Download Mac

firewatch download torrent mac The Forest Free Download Mac. Nov 23, 2020 — Into the Forest PC Game Walkthrough Free Download for Mac Full version highly compressed via direct link. Into the Forest PC Game Free …. Feb 1, 2007 — Download Forest Resort Mac for Mac to collect magic to restore the forest while attending to your customers.. May 4, 2019 — The Forest free download! Download here for free! Just download and play for PC! Cracked by CPY, CODEX and SKIDROW! Free Digital College Planner Printables + Stickers. I have been out of college for a few years now, but my little brother in law … forest app. forrest gump, forrest gump quotes, forrest fenn, forrest galante, forrest fenn treasure, forest, forest whitaker, forester, forrest, forestry, forest game, forest app, forest korean drama, forest cartoon, forest green, forest of dean. RevMan Web is the online platform recommended for Cochrane intervention and flexible reviews. Log in to RevMan Web to access your review. RevMan 5 is free … forest game. Forest is an app helping you stay away from your smartphone and stay focused on your work.. The Forest Free Download PC Game Latest Update DMG For Mac OS Android APK Free Download PC Games Highly Compressed Direct Download In Parts …. Download Forest for Mac – Stay focused on your work and avoid time wasting websites with the help of this cute extension that comes with support for Chrome … Firewatch PC Game Free Download. Dalam Firewatch, Anda akan memerankan seorang tokoh bernama Henry. Ketika sedang melakukan patroli di hutan, dirinya mendapati bahwa menara pengawas telah diobrak-abrik oleh orang lain. -

Art Worlds for Art Games Edited

Loading… The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association Vol 7(11): 41-60 http://loading.gamestudies.ca An Art World for Artgames Felan Parker York University [email protected] Abstract Drawing together the insights of game studies, aesthetics, and the sociology of art, this article examines the legitimation of ‘artgames’ as a category of indie games with particularly high cultural and artistic status. Passage (PC, Mac, Linux, iOS, 2007) serves as a case study, demonstrating how a diverse range of factors and processes, including a conducive ‘opportunity space’, changes in independent game production, distribution, and reception, and the emergence of a critical discourse, collectively produce an assemblage or ‘art world’ (Baumann, 2007a; 2007b) that constitutes artgames as legitimate art. Author Keywords Artgames; legitimation; art world; indie games; critical discourse; authorship; Passage; Rohrer Introduction The seemingly meteoric rise to widespread recognition of ‘indie’ digital games in recent years is the product of a much longer process made up of many diverse elements. It is generally accepted as a given that indie games now play an important role in the industry and culture of digital games, but just over a decade ago there was no such category in popular discourse – independent game production went by other names (freeware, shareware, amateur, bedroom) and took place in insular, autonomous communities of practice focused on particular game-creation tools or genres, with their own distribution networks, audiences, and systems of evaluation, only occasionally connected with a larger marketplace. Even five years ago, the idea of indie games was still burgeoning and becoming stable, and it is the historical moment around 2007 that I will address in this article. -

Video Game Developer Pdf, Epub, Ebook

VIDEO GAME DEVELOPER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chris Jozefowicz | 32 pages | 15 Aug 2009 | Gareth Stevens Publishing | 9781433919589 | English | none Video Game Developer PDF Book Photo Courtesy: InnerSloth. Upon its launch, Will of the Wisps made waves for frame-rate issues and bugs, but after those were quickly patched, it was easy to fall in love with every aspect of the game. Video game designers need to have analytical knowledge as well as strong creative skills. First, make sure you have a good computer with some processing power and the right software. It takes cues from choose-your-own-adventure novels as well as some of the earliest narrative-driven video games from the '70s and '80s, including the first-known work of interactive fiction, Colossal Cave Adventure. Check out the story of the whirlwind visit and hear about our first peek at the game. From its dances to its massive tournaments, Fortnite has won over gamers around the world. Are there video games designed for moms? This phase can take as many hours as the original creation of the game. In Animal Crossing , you play as a human character who moves to a new town — in the case of New Horizons , your character moves to a deserted island at the invitation of series regular Tom Nook, a raccoon "entrepreneur. One standout aspect of the game was its music. If you've ever gotten immersed in your game character's story and movements, you've probably wondered how these creations can move so fluidly. How MotionScan Technology Works Animation just keeps getting more and more realistic, as emerging technology MotionScan demonstrates quite nicely.