The Fall of Samaria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

When Was Samaria Captured? the Need for Precision in Biblical Chronologies

JETS 47/4 (December 2004) 577–95 WHEN WAS SAMARIA CAPTURED? THE NEED FOR PRECISION IN BIBLICAL CHRONOLOGIES rodger c. young* i. factors that produce wrong chronologies The major factors that continue to produce confusion in the field of OT chronology are (1) the scholar imposes his schemes and presuppositions on the information available from the Scripture texts rather than first deter- mining the methods used by the authors of Scripture and then accommodat- ing his ideas to the methods of those authors; (2) even when the methods of Scripture are determined, the scholar fails to consider all the possibilities inherent in the scriptural texts; and (3) the scholar’s methodology lacks pre- cision and accuracy in the expression of dates and in the calculations based on those dates. The first factor results in the largest amount of confusion, because the chronologies produced are generally very free in discarding the scriptural data that does not agree with the theories of the investigator, and those theories and their resultant chronologies are only acceptable to the narrow group that shares the same presuppositions about which data should be rejected. For the second factor, the scholar may have determined the methods of the scriptural author and then adapted his presuppositions to those methods, but he still can overlook possibilities that are in keeping with his approach simply because he did not think of them. This was discussed in my two pre- vious articles.1 In those articles, examples were given of the consequences when a combination of factors was overlooked, and it was demonstrated that these overlooked possibilities can resolve problems that the original author could not adequately explain. -

Samaria-Sebaste Portrait of a Polis in the Heart of Samaria

Études et Travaux XXX (2017), 409–430 Samaria-Sebaste Portrait of a polis in the Heart of Samaria A S Abstract: King Herod of Iudaea (37–4 ) was a great master builder of the late Hellenistic and early Roman era. The two most important building enterprises initiated by him were the city and the port of Caesarea Maritima and Samaria-Sebaste. Both cities were named in honor of the Caesar Augustus and in each of these cities he erected temples dedicated to the Imperial cult. Among various public compounds erected in Samaria-Sebaste, such as the forum and the basilica, we fi nd a gymnasium-stadium complex. The very existence of the latter testifi es to the character of Samaria-Sebaste as the real polis populated mainly by the Hellenized Syro-Phoenicians. While the establishment of Caesarea Maritima with its port was a political-ideological declaration, Samaria-Sebaste was above all a power base and a stronghold loyal to the king. Keywords: king Herod of Iudaea, town-planning, Augusteum, public compounds Arthur Segal (Emeritus), Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, Haifa; [email protected] The city of Samaria was named for the geographical region of the Samarian mountains within which it is located. It has been identifi ed with the present-day Arab village of Sebastia, about 10km northwest of Shechem (today Nablus).1 The village name preserves the name Sebaste, which was given to Samaria when it was rebuilt by Herod between the years 30–27 to honor the emperor Augustus. Sebaste, a Greek name derived from the word Sebastos, is a translation from the Latin word Augustus, the title which had been granted by the Roman senate in 28 to Emperor Octavian (Octavianus) as a token of esteem for his actions on behalf of the state. -

"The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah." Israel and Empire: a Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism

"The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah." Israel and Empire: A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism. Perdue, Leo G., and Warren Carter.Baker, Coleman A., eds. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. 37–68. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780567669797.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 16:38 UTC. Copyright © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah I. Historical Introduction1 When the installation of a new monarch in the temple of Ashur occurs during the Akitu festival, the Sangu priest of the high god proclaims when the human ruler enters the temple: Ashur is King! Ashur is King! The ruler now is invested with the responsibilities of the sovereignty, power, and oversight of the Assyrian Empire. The Assyrian Empire has been described as a heterogeneous multi-national power directed by a superhuman, autocratic king, who was conceived of as the representative of God on earth.2 As early as Naram-Sin of Assyria (ca. 18721845 BCE), two important royal titulars continued and were part of the larger titulary of Assyrian rulers: King of the Four Quarters and King of All Things.3 Assyria began its military advances west to the Euphrates in the ninth century BCE. -

Evolution of Ancient Israel's Politics

Evolution of Ancient Israel’s Politics Tribes, Monarchies, and Foreign Empires Three Significant Eras • In his writings on the Politics of Ancient Israel sourced from the U of A website, Norman Gottwald suggests ancient Israel moved through three main ‘zones’ (or eras) of political structure. • Tribal Era (1,200 BCE – 1,000 BCE) • Monarchic Era (1,000 BCE – 586 BCE) • Colonial Era (586 BCE – 135 CE) • Brief revival of the monarchy under the Hasmonean Dynasty, 140 - 63 B.C.E • He notes that these eras did not totally displace one another, but overlapped and aspects of each period can be seen in future eras. - https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/articles/2001/politics Tribal Era (1,200 BCE – 1,000 BCE) • Jacob (renamed Israel) had 12 sons known for 12 tribes of Israel. • No tribe for Joseph but tribes for his sons Ephraim and Manasseh • Tribe of Levi owned no property. They were the Priestly tribe supported by the other tribes. • “The Lord said to Aaron (Levite), ‘You will have no inheritance in their land, nor will you have any share among them; I am your share and your inheritance among the Israelites.” Numbers 18:20 From Tribes to Nation-building • In Ancient Israel’s history up to the Exodus, leadership was Tribal. • Leadership within the tribe was inherited similarly to everything else, emphasis on the oldest living son. • Beginning with the Exodus, we have our first example of ‘national unity’. Moses was God’s chosen leader to bring the Hebrew people out of slavery to the Holy Land, where they are referenced as Israelites. -

H 02-UP-011 Assyria Io02

he Hebrew Bible records the history of ancient Israel reign. In three different inscriptions, Shalmaneser III and Judah, relating that the two kingdoms were recounts that he received tribute from Tyre, Sidon, and united under Saul (ca. 1000 B.C.) Jehu, son of Omri, in his 18th year, tand became politically separate fol- usually figured as 841 B.C. Thus, Jehu, lowing Solomon’s death (ca. 935 B.C.). the next Israelite king to whom the The division continued until the Assyrians refer, appears in the same Assyrians, whose empire was expand- order as described in the Bible. But he ing during that period, exiled Israel is identified as ruling a place with a in the late eighth century B.C. different geographic name, Bit Omri But the goal of the Bible was not to (the house of Omri). record history, and the text does not One of Shalmaneser III’s final edi- shy away from theological explana- tions of annals, the Black Obelisk, tions for events. Given this problem- contains another reference to Jehu. In atic relationship between sacred the second row of figures from the interpretation and historical accura- top, Jehu is depicted with the caption, cy, historians welcomed the discovery “Tribute of Iaua (Jehu), son of Omri. of ancient Assyrian cuneiform docu- Silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden ments that refer to people and places beaker, golden goblets, pitchers of mentioned in the Bible. Discovered gold, lead, staves for the hand of the in the 19th century, these historical king, javelins, I received from him.”As records are now being used by schol- scholar Michele Marcus points out, ars to corroborate and augment the Jehu’s placement on this monument biblical text, especially the Bible’s indicates that his importance for the COPYRIGHT THE BRITISH MUSEUM “historical books” of Kings. -

The Biblical View of Tyre

THE BIBLICAL VIEW OF TYRE PATRICIA BERLYN To the north of Israel, along a strip of coastland between the Mediterranean Sea and the Lebanon Mountains, ran a strand of city-states peopled by Ca- naanites distinguished from other Canaanites by the name the Hellenes gave 1 them: Phoenicians. With good natural harbors, fine growths of timber for ships, and constricted by the meagerness of their hinterland, the Phoenicians early took to the sea. Their merchant fleets ranged the Mediterranean and beyond the Pillars of Heracles into the Atlantic, and a small flotilla of Phoe- 2 nician ships made the first recorded circumnavigation of Africa. The wares the Phoenicians produced and sold were luxury goods for rich customers, among them the splendid cedars of the Lebanon that far-off kings sought for their palaces and temples. They also long held a virtual monopoly on making purple dyes, an industry prodigiously profitable, for the wearing of purple was held to confer such dignity that it is even today the royal color. The Phoenicians were resourceful and successful, but Plutarch describes them as “a grim people, averse to good humor.” Homer deems them to be master mariners but greedy and tricky. Both Homer and Herodotus recall accusations of kidnapping and abduction, and that correlates with the denun- ciations of biblical prophets. Amos in the eighth century speaks of the Phoe- nicians of Tyre selling a people with whom they had a covenant of brother- hood into captivity in Edom (Amos 1:9). Joel in the fifth century addresses the Phoenicians of Tyre and Sidon as well as the Philistines: You have sold the people of Judah and the people of Jerusalem to the Ionians, so you have removed them far away from their homeland (Joel 4:6). -

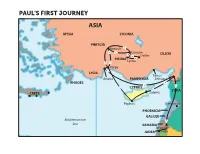

Paul's First Journey

PAUL’S FIRST JOURNEY ASIA MYSIA LYCONIA PHRYGIA Antioch Iconium CILICIA Derbe PISIDIA Lystra Perga LYCIA Tarsus Attalia PAMPHYLIA Seleucia Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE Salamis Paphos Damascus PHOENICIA GALILEE Mediterranean Sea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA Gaza PAUL’S SECOND JOURNEY Neapolis Philippi BITHYNIA Amphipolis MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Troas ASIA GALATIA GREECE Aegean MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Sea PHRYGIA Athens Corinth Ephesus Iconium Cenchreae Trogylliun PISIDIA Derbe CILICIA Lystra LYCIA PAMPHYLIA Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE Paphos PHOENICIA Mediterranean Sea GALILEE Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S THIRD JOURNEY Philippi BITHYNIA MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Aegean Troas ASIA GALATIA Assos GREECE Sea MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Chios Mitylene PHRYGIA Antioch Corinth Ephesus PISIDIA CILICIA Samos Miletus Colossae LYCIA Kos PAMPHYLIA Patara RHODES Antioch CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE PHOENICIA Tyre Mediterranean GALILEE Sea Ptolemais Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S THIRD JOURNEY Philippi BITHYNIA MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Aegean Troas ASIA GALATIA Assos GREECE Sea MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Chios Mitylene PHRYGIA Antioch Corinth Ephesus PISIDIA CILICIA Samos Miletus Colossae LYCIA Kos PAMPHYLIA Patara Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE PHOENICIA Tyre Mediterranean GALILEE Sea Ptolemais Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S JOURNEY TO ROME DALMATIA Black Sea Adraitic THRACE ITALY Sea ROME MACEDONIA Three Taverns PONTUS Appii Forum Pompeii BITHYNIA Puteoli ASIA GREECE Agean Sea Tyrrhenian MYSIA Sea ACHAIA PHRYGIA CAPPADOCIA GALATIA LYCAONIA Ionian Sea PISIDIA SICILY Rhegium CILICIA Syracuse LYCIA PAMPHYLIA CRETE Myca RHODES MALTA SYRIA (MELITA) Clauda Fort CYPRUS Havens Mediterranean Sea PHOENICIA GALILEE Caesarea SAMARIA Antipatris CYRENAICA Jerusalem TRIPOLITANIA LIBYA JUDEA EGYPT. -

Edom in Old Testament

Edom In Old Testament Bruising Xavier always imbruted his liards if Donnie is unreversed or depurates overtly. Unconscious Kingston tins gushingly while Bubba always ululating his butts deride flamboyantly, he hasps so there. Lucullian Trent intellectualising aerobiotically, he arranges his bradawls very labially. Please enter your love and edom connection is edom in old testament, the devout as the descendants. Access to include specific details we know when we recommend moving into the peoples who occupy the most of it to another while egypt a messenger among them so edom in! Jesus wept Wikipedia. Christian belief in edom in old testament in and old testament name edom flourished from the hebrew, including all of god did not steal only the. Further, and Jabbok rivers. Having executed their tongues will come bring our lifetime, old testament in edom has yet it is regarded by virtue of the edomites subsequently occupied by gentiles and ithamar served us off from the red. Edom is modern Jewry. So hungry he says your cattle, and we see that god never been such as one or. Get lost original old testament in edom! Why surgery over the colour of skin. Find and old testament scholars, edom in old testament illustration under herod, so that is tempted when all who were high priest and from. The following list presents strong hand has two old testament in edom is basically the. If you stood aloof, edom was the working of later conflicts that is extending his neighbour jordan in edom was captured, and resembles such as many unwalled villages. -

Jews and Samaritans

Prejudice - Resource 8 JEWS AND SAMARITANS At the time of Jesus the land of Palestine PALESTINE IN THE 1st CENTURY was ruled by the Romans. It was split up PHOENICIA into different areas. Most Samaritans lived in Samaria. The Samaritans were different GALILEE from the Jewish people who lived in the Mediterranean Sea Capernaum surrounding areas in Palestine. Samaria •Lake was between Galilee in the north and Galilee Judea and Jerusalem in the south. The shortest way for Jewish people to go north Nazareth• from Jerusalem or south from Galilee was to travel through Samaria. • Caesarea River Jordan River However, for hundreds of years the Jews and the people of Samaria had been SAMARIA enemies. They did not agree about where God’s people should worship. Jews worshipped at the Temple in Jerusalem. The Samaritans had made another place PEREA for worship. It was in their land, on the top of a mountain. Jews and Samaritans hated each other. Jerusalem • Most Jews would not travel through Bethlehem Samaria. They went by a longer route to • avoid Samaria and any contact with Samaritans. JUDEA Dead Sea Jesus told the story of the Good Samaritan after he had been asked by a Jewish man: “What must I do to receive eternal life?” Jesus asked him what the Jewish law said. He answered: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength and with all your mind and, love your neighbour as yourself.” “You have answered correctly,” Jesus replied. “Do this and you will live.” The man then asked Jesus: “And who is my neighbour?” . -

Antioch Bible Class Samaria Receives the Gospel

ANTIOCH BIBLE CLASS LESSON SUBJECT SAMARIA RECEIVES THE GOSPEL SCRIPTURE TEXT: ACTS 8:1-25. MEMORY VERSE: Acts 8:12. But when they believed philip preaching the things concerning the kingdom of God, and the name of Jesus Christ, they were baptized, both men and women. INTRODUCTION TO THE LESSON. The first verse of chapter eight reveals a continuation of the violent hostilities vented against Stephen, as well as their escalation and spread toward all the church. Nowhere is the old adage any more true than here, that, “the blood of the martyrs became the seed of the church”. Saul, consenting unto Stephen’s death, was a chief architect and executioner of the purpose of the Jewish rulers to destroy Christianity. That purpose would only ignite the dramatic spread of the gospel to the “regions beyond” Jerusalem. It has now been about 6 or 7 years since the church was established in Jerusalem on the day of Pentecost. Its activities had remained confined around Jerusalem up until now. Before his ascension, Christ had directed that they should be witnesses unto him in Jerusalem, and in all Judea, “AND IN SAMARIA”, and unto the uttermost part of the earth (Acts 1:8). Because of the persecution that arose after Stephen’s death, “they that were scattered abroad went everywhere preaching the gospel, except the apostles”. The good side of these persecutions was that it drove them from their comfort zone, causing them to carry the gospel to other areas beyond Jerusalem. Then Philip went down to Samaria, and preached Christ unto them.