Cairo New Cities Ericdenis VF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 in Collaboration With

know more.. Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 In collaboration with -PB- -1- -2- -1- Know more.. Continuing on the momentum of our brand’s focus on knowledge sharing, this year we lay on your hands the most comprehensive and impactful set of data ever released in Egypt’s real estate industry. We aspire to help our clients take key investment decisions with actionable, granular, and relevant data points. The biggest challenge that faces Real Estate companies and consumers in Egypt is the lack of credible market information. Most buyers rely on anecdotal information from friends or family, and many companies launch projects without investing enough time in understanding consumer needs and the shifting demand trends. Know more.. is our brand essence. We are here to help companies and consumers gain more confidence in every real estate decision they take. -2- -1- -2- -3- Research Methodology This report is based exclusively on our primary research and our proprietary data sources. All of our research activities are quantitative and electronic. Aqarmap mainly monitors and tracks 3 types of data trends: • Demographic & Socioeconomic Consumer Trends 1 Million consumers use Aqarmap every month, and to use our service they must register their information in our database. As the consumers progress in the usage of the portal, we ask them bite-sized questions to collect demographic and socioeconomic information gradually. We also send seasonal surveys to the users to learn more about their insights on different topics and we link their responses to their profiles. Finally, we combine the users’ profiles on Aqarmap with their profiles on Facebook to build the most holistic consumer profile that exists in the market to date. -

Reserve Great Apartment in New Heliopolis Near El Shorouk City

Reserve great apartment in new Heliopolis near el shorouk city Reference: 21037 Property Type: Apartments Property For: Sale Price: 675,000 EGP Country: Egypt Region: Cairo City: New Heliopolis Property Address: New Heliopolis cairo Price: 675,000 EGP Completion Date: 1970-01-01 Surface Area: 135 Unit Type: Flat Floor No: 03 No of Bedrooms: 2 No of Bathrooms: 1 Flooring: Cement Facing: North View: landscabe view Maintenance Fees: 5 % Deposit Union landlords Year Built: 2018 Real Estate License: residential Ownership Type: Registered Description: [tag]New Heliopolis[/tag] The total area of the city is 5888 acres made up of comprehensive residential places, services, recreational, educational, commercial, administrative, medical, social clubs, green open areas and the Golf. The Heliopolis Company for Development and housing was and is still the godfather of the city, providing all the facilities and services for the residents of the city including: Internal map of the city * Security gates * Integrated electricity network * Educational areas (schools- Institutes - Universities) The city is connected by the Cairo-Ismailia road from the north and by the CairoSuez road from the south. It also borders Madinaty to the south, El Shorouk to the west and Badr to the east. The city benefits from its connection to the Regional Ring Road which links it to all of Greater Cairo. The city is located 25 minutes from the district of Heliopolis and Nasr City Features: Elevator Balcony + View Master Bedroom Garage Close to the city Terrace Near Transport Luxury building Residential Area Quiet Area Shopping nearby Security Services . -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

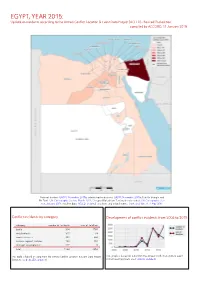

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

To Whom Do Minbars Belong Today?

Besieging Freedom of Thought: Defamation of religion cases in two years of the revolution The turbaned State An Analysis of the Official Policies on the Administration of Mosques and Islamic Religious Activities in Egypt The report is issued by: Civil Liberties Unite August 2014 Designed by: Mohamed Gaber Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 14 Al Saraya Al Kobra St. First floor, flat number 4, Garden City, Cairo, Telephone & fax: +(202) 27960197 - 27960158 www.eipr.org - [email protected] All printing and publication rights reserved. This report may be redistributed with attribution for non-profit pur- poses under Creative Commons license. www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Amr Ezzat: Researcher & Officer - Freedom of Religion and Belief Program Islam Barakat and Ibrahim al-Sharqawi helped to compile the material for this study. The Turbaned State: An Analysis of the Official Policies on the Administration of Mosques and Islamic Religious Activities in Egypt Summary: Policies Regulating Mosques: Between the Assumption of Unity and the Reality of Diversity Along with the rapid political and social transformations which have taken place since January 2011, religion in Egypt has been a subject of much contention. This controversy has included questions of who should be allowed to administer mosques, speak in them, and use their space. This study observes the roots of the struggle over the right to administer mosques in Islamic jurisprudence and historical practice as well as their modern implications. The study then moves on to focus on the developments that have taken place in the last three years. The study describes the analytical framework of the policies of the Egyptian state regarding the administration of mosques, based on three assumptions which serve as the basis for these policies. -

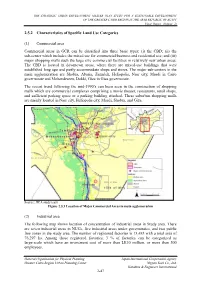

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

Egypt Weekly Newsletter November 2014, 2Nd Quarter

EGYPT WEEKLY NEWSLETTER November, 2014 (2nd QUARTER) CONTENT 1. Political Overview………..........01 2. Economic Overview……..….…..02 3. Finance..…………………………..….05 4. IT & Telecom………………………..05 5. Energy……………………………….… 06+ 6. Agriculture.…..……..………………07 7. Building Materials……..…………08 8. Real Estate.…………..……..……...08 9. Laws & Regulations…..…………. 08 10. Hot Issue……………………….……09 Compiled by Thai Trade Center, Cairo POLITICAL OVERVIEW Parliamentary polls to be held before end of March, says El-Sisi Source: Egypt Impendent, November 13, 2014 Egypt's president Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi said in a meeting with a delegation of American businesspeople on Monday that Egyptian parliamentary elections will take place before the end of March 2015. The statement is the closest estimate given by an official regarding the date of the polls, which has been shrouded in mystery for quite some time. A statement by presidential spokesman Alaa Youssef said El-Sisi mentioned that the third objective of Egypt's transitional roadmap, following a new constitution and presidential elections, "will be achieved before the International Economic Summit which Egypt will host in the first quarter of 2015." The delay of a date for elections was criticised by politicians and observers who have argued the delay is unconstitutional; Egypt's January 2014 constitution says electoral procedures for parliamentary elections must commence after 6 months following the constitution’s ratification. The meeting included representatives from the Egypt-US Business Council and the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt. Egypt Prime Minister Ibrahim Mahlab attended the meeting along with many members of cabinet including the industry and trade, planning, investment, electricity and renewable energy and petroleum ministries. -

Pdf 584.52 K

3 Egyptian J. Desert Res., 66, No. 1, 35-55 (2016) THE VERTEBRATE FAUNA RECORDED FROM NORTHEASTERN SINAI, EGYPT Soliman, Sohail1 and Eman M.E. Mohallal2* 1Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, El-Abbaseya, Cairo, Egypt 2Department of Animal and Poultry Physiology, Desert Research Center, El Matareya, Cairo, Egypt *E-mail: [email protected] he vertebrate fauna was surveyed in ten major localities of northeastern Sinai over a period of 18 months (From T September 2003 to February 2005, inclusive). A total of 27 species of reptiles, birds and mammals were recorded. Reptiles are represented by five species of lizards: Savigny's Agama, Trapelus savignii; Nidua Lizard, Acanthodactylus scutellatus; the Sandfish, Scincus scincus; the Desert Monitor, Varanus griseus; and the Common Chamaeleon, Chamaeleo chamaeleon and one species of vipers: the Sand Viper, Cerastes vipera. Six species of birds were identified during casual field observations: The Common Kestrel, Falco tinnunculus; Pied Avocet, Recurvirostra avocetta; Kentish Plover, Charadrius alexandrines; Slender-billed Gull, Larus genei; Little Owl, Athene noctua and Southern Grey Shrike, Lanius meridionalis. Mammals are represented by 15 species; Eleven rodent species and subspecies: Flower's Gerbil, Gerbillus floweri; Lesser Gerbil, G. gerbillus, Aderson's Gerbil, G. andersoni (represented by two subspecies), Wagner’s Dipodil, Dipodillus dasyurus; Pigmy Dipodil, Dipodillus henleyi; Sundevall's Jird, Meriones crassus; Negev Jird, Meriones sacramenti; Tristram’s Jird, Meriones tristrami; Fat Sand-rat, Psammomys obesus; House Mouse, Mus musculus and Lesser Jerboa, Jaculus jaculus. Three carnivores: Red Fox, Vulpes vulpes; Marbled Polecat, Vormela peregosna and Common Badger, Meles meles and one gazelle: Arabian Gazelle, Gazella gazella. -

Local Development Ii Urban Project

LOCAL DEVELOPMENT II URBAN PROJECT Submited to USAID /CAIRO Submitted by WILBUR SMITH ASSOCIATES inassociation with PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION SERVICE DELOITTE AND TOUCHE DEVELOPMENT CON-JLTING OFFICE ENGINEERING AND GEOLOGICAL CONSULTING OFFICE REPORT ON SUII-PROJECI' RNING FOR i'ROJIICIN CARRIED OUT DURING FY 1988 DECMBER 1990 Submitted to USAID/CAIRO Submitted by WILBUR SMITl ASSOCIATES Public Administration Service Dcloit & Touch Dcvclopmcnt Consulting Officc Enginecring & Geological Consulting Office 21-S.663 TABLE OF CONTENTS Subject Page No. 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. DESIGN 2 2.1 General 2 2.2 Project Documents 2 2.3 Conclusions 2 3. COST ESTIMATES 7 3.1 General 7 3.2 Conclusions 7 4. CONSTRUCTION QUALITY CONTROL/SCHEDULING 11 4.1 General 11 4.2 Conclusion 11 5. IMPLEMENTATION AND OPERATION 20 5.1 General 20 5.2 Breakdown of Sectors-Implementation 20 5.3 Breakdown of Sectors-Operation 21 5.4 Analysis by Sector 21 6. INCOME GENERATION 51 6.1 Cost Recovery 51 7. MAINTENANCE 58 7.1 General 58 7.2 Education Sector 58 7.3 Conclusions 59 8. USAID PLAQUES 65 9. SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS 67 APPENDICES: Sub-Project Profile FY 88 a-1 Rating Field Work Sheets b-I/b-5 LIST OF TABLES Table No. Page No. 2-1 Adequacy of Design 5 2-2 Adequacy of Design (Standard Deviation) 7 3-1 Adherence to Estimated Cost 9 3-2 Adherence to Contract Cost 10 4-1 Adequacy of Construction 13 4-2 Adequacy of Construction (Standard Deviation) 15 4-3 Adherence to Schedule - Construction 16 4-4 Adherence to Schedule - Equipment 17 4-5 Adherence to Schedule - Utilities 18 4-6 Adequacy -

“Jesters Do Oft Prove Prophets” William Shakespeare King Lear (Act 5, Scene 3)

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION “Jesters do oft prove prophets” William Shakespeare King Lear (Act 5, Scene 3) During Medieval times, kings kept jesters for amusement and telling jokes. Jesters played the role of both entertainers and advisers, sarcastically mocking reality to entertain and amuse. The jester’s unique position in the court allowed him to tell the king the truth upfront that no one else dared to speak, under the cover of telling it as a jest (Glenn, 2011). In this sense, contemporary political satire has given birth to many modern-day jesters, one of the most famous worldwide being Jon Stewart, and on a more local scale but also gaining widespread popularity, Bassem Youssef. Political satire is a global genre. It dates back to the 1960s, originating in Britain, and has now become transnational, with cross-cultural flows of the format popular and flourishing across various countries (Baym & Jones, 2012). The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report are examples of popular political satire shows in the United States. Both shows have won Emmy awards and Jon Stewart was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world. Research on political satire shows that it does not have unified effects on its audiences. Different types of satire lead to distinct influences on viewers (Baumgartner & Morris, 2006; Baumgartner & Morris, 2008; Holbert et al, 2013; Lee, 2013). Moreover, viewers of different comedy shows are not homogeneous in nature. The Daily Show's audience was found to be more politically interested and knowledgeable than Leno and Letterman viewers (Young & Tisinger, 2006). -

Resistant Escherichia Coli: a Risk to Public Health and Food Safety

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Poultry hatcheries as potential reservoirs for antimicrobial- resistant Escherichia coli: A risk to Received: 12 September 2017 Accepted: 21 March 2018 public health and food safety Published: xx xx xxxx Kamelia M. Osman1, Anthony D. Kappell2, Mohamed Elhadidy3,4, Fatma ElMougy5, Wafaa A. Abd El-Ghany6, Ahmed Orabi1, Aymen S. Mubarak7, Turki M. Dawoud7, Hassan A. Hemeg8, Ihab M. I. Moussa7, Ashgan M. Hessain9 & Hend M. Y. Yousef10 Hatcheries have the power to spread antimicrobial resistant (AMR) pathogens through the poultry value chain because of their central position in the poultry production chain. Currently, no information is available about the presence of AMR Escherichia coli strains and the antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) they harbor within hatchezries. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the possible involvement of hatcheries in harboring hemolytic AMR E. coli. Serotyping of the 65 isolated hemolytic E. coli revealed 15 serotypes with the ability to produce moderate bioflms, and shared susceptibility to cephradine and fosfomycin and resistance to spectinomycin. The most common β-lactam resistance gene was blaTEM, followed by blaOXA-1, blaMOX-like, blaCIT-like, blaSHV and blaFOX. Hierarchical clustering of E. coli isolates based on their phenotypic and genotypic profles revealed separation of the majority of isolates from hatchlings and the hatchery environments, suggesting that hatchling and environmental isolates may have diferent origins. The high frequency of β-lactam resistance genes in AMR E. coli from chick hatchlings indicates that hatcheries may be a reservoir of AMR E. coli and can be a major contributor to the increased environmental burden of ARGs posing an eminent threat to poultry and human health. -

Egypt and Ethiopia.Pdf

Egypt and Ethiopia The history of Egyptian-Ethiopian relations dates back to the Ancient Egypt eras, which were not only political but religious and cultural relations as well. The Religious relations between the two countries began in the 4th century AD since the Ethiopian Church was associated with the Egyptian Church, while the signs of concord were the affiliation of the Ethiopian Church to one faith and one Bishop, who is Egyptian, where all Ethiopian clerics are attached to him functionally and ideologically. There was mutual respect between the Emperor and the Egyptian Bishop. The current distinguished cooperation between Egypt and Ethiopia in the water issue, which is considered a national security issue, proved to the whole world that Cairo and Addis Ababa are brothers and the positive cooperation in this issue will be based on this historical depth in the relations between the two countries. This comes in the framework of the development and change taking place in Ethiopia, which necessitates the continuation of channels of communication and open dialogue between the two countries to facilitate the common vision of bilateral relations, as well as the issues related to the management of the Renaissance Dam file, the full implementation of the agreements concluded and strengthening the Egyptian-Ethiopian relations in all fields to meet the aspirations of the peoples of the two countries.. We review in the following lines two sections; the first section dealing with the central aspects of the relations between the two countries, while the second one monitors their development in the political, economic, religious and educational aspects.