Art, Science and the Remains of Roman Britain Sarah Scott*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña ISSN: 1659-4223 Universidad de Costa Rica Prescott, Andrew; Sommers, Susan Mitchell En busca del Apple Tree: una revisión de los primeros años de la masonería inglesa Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña, vol. 9, núm. 2, 2017, pp. 22-49 Universidad de Costa Rica DOI: 10.15517/rehmlac.v9i2.31500 Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369556476003 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto REHMLAC+, ISSN 1659-4223, vol. 9, no. 2, diciembre 2017-abril 2018/19-46 19 En busca del Apple Tree: una revisión de los primeros años de la masonería inglesa Searching for the Apple Tree: Revisiting the Earliest Years of Organized English Freemasonry Andrew Prescott Universidad de Glasgow, Escocia [email protected] Susan Mitchell Sommers Saint Vincent College en Pennsylvania, Estados Unidos [email protected] Recepción: 20 de agosto de 2017/Aceptación: 5 de octubre de 2017 doi: https://doi.org/10.15517/rehmlac.v9i2.31500 Palabras clave Masonería; 300 años; Gran Logia; Londres; Taberna Goose and Gridiron. Keywords Freemasonry; 300 years; Grand Lodge; London; Goose and Gridiron Tavern. Resumen La tradición relata que el 24 de junio de 1717 cuatro logias en la taberna londinense Goose and Gridiron organizaron la primera gran logia de la historia. -

The Garden Designs of William Stukeley (1687–1765)

2-4 GS Reeve + RS CORR NEW_baj gs 4/9/13 10:02 PM Page 9 The BRITISH ART Journal Volume XIII, No. 3 Of Druids, the Gothic, and the origins of architecture The garden designs of William Stukeley (1687–1765) Matthew M Reeve illiam Stukeley’s central place in the historiogra- phy of eighteenth-century England is hardly Winsecure.1 His published interpretations of the megalithic monuments at Avebury (1743) and Stonehenge (1740) earned him a prominent position in the history of archaeology, and his Vetusta Monumenta ensured his rep- utation as a draughtsman and antiquarian. Recent research has shown that Stukeley was a polymath, whose related interests in astrology, Newtonian natural history and theol- ogy formed part of a broader Enlightenment world view.2 Yet, in the lengthy scholarship on Stukeley, insufficient attention has been paid to his interest in another intellectu- al and aesthetic pursuit of eighteenth-century cognoscenti: garden design.3 Stukeley’s voluminous manuscripts attest to his role as an avid designer of gardens, landscapes and garden build- ings. His own homes were the subjects of his most interesting achievements, including his hermitages at Kentish Town (1760), Stamford (Barnhill, 1744 and Austin Street 1737), and Grantham (1727).4 In this, Stukeley can be located among a number of ‘gentleman gardeners’ in the first half of the eighteenth century from the middling classes and the aristocracy.5 He toured gardens regularly, and recorded many of them in his books, journals and cor- respondence. His 1724 Itinerarium Curiosum recounts his impressions of gardens, including the recent work at Blenheim Palace and the ‘ha-ha’ in particular, and his unpublished notebooks contain a number of sketches such as the gardens at Grimsthorpe, Lincs., where he was a reg- ular visitor.6 Stukeley also designed a handful of garden buildings, apparently as gifts for friends and acquaintances. -

Tate Report 08-09

Tate Report 08–09 Report Tate Tate Report 08–09 It is the Itexceptional is the exceptional generosity generosity and and If you wouldIf you like would to find like toout find more out about more about PublishedPublished 2009 by 2009 by vision ofvision individuals, of individuals, corporations, corporations, how youhow can youbecome can becomeinvolved involved and help and help order of orderthe Tate of the Trustees Tate Trustees by Tate by Tate numerousnumerous private foundationsprivate foundations support supportTate, please Tate, contact please contactus at: us at: Publishing,Publishing, a division a divisionof Tate Enterprisesof Tate Enterprises and public-sectorand public-sector bodies that bodies has that has Ltd, Millbank,Ltd, Millbank, London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG helped Tatehelped to becomeTate to becomewhat it iswhat it is DevelopmentDevelopment Office Office www.tate.org.uk/publishingwww.tate.org.uk/publishing today andtoday enabled and enabled us to: us to: Tate Tate MillbankMillbank © Tate 2009© Tate 2009 Offer innovative,Offer innovative, landmark landmark exhibitions exhibitions London LondonSW1P 4RG SW1P 4RG ISBN 978ISBN 1 85437 978 1916 85437 0 916 0 and Collectionand Collection displays displays Tel 020 7887Tel 020 4900 7887 4900 A catalogue record for this book is Fax 020 Fax7887 020 8738 7887 8738 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. DevelopDevelop imaginative imaginative education education and and available from the British Library. interpretationinterpretation programmes programmes AmericanAmerican Patrons Patronsof Tate of Tate Every effortEvery has effort been has made been to made locate to the locate the 520 West520 27 West Street 27 Unit Street 404 Unit 404 copyrightcopyright owners ownersof images of includedimages included in in StrengthenStrengthen and extend and theextend range the of range our of our New York,New NY York, 10001 NY 10001 this reportthis and report to meet and totheir meet requirements. -

In 1968. the Report Consists of the Following Parts: L the Northgate Turnpike Roads 2 Early Administration and the Turnpike Trust

Reprinted from: Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1971 pages 1-58 [This edition was reprinted in 1987 by the Author in Hong Kong with corrections and revised pagination] THE NQRIH§AIE.IHBNBlKE N SPRY For more than one hundred and seventy years the road from the city of Gloucester to the top of Birdlip Hill, and the road which branched eastwards from it up Crickley Hill towards Oxford and later London, was maintained from the proceeds of the various turnpikes or toll gates along it. This report examines the history and administration of these roads from their earliest period to the demise of the Turnpike Trust in l87l and also details excavations across the road at Wotton undertaken in 1968. The report consists of the following Parts: l The Northgate Turnpike roads 2 Early administration and the Turnpike Trust 3 Tolls, exemptions and traffic 4 Road materials 5 Excavations at Wotton 1968 I Summary II The Excavations III Discussion References 1 IHE.NQBIH§AIE.BQADfi The road to Gloucester from Cirencester and the east is a section of the Roman road known as Ermine Street. The line of this road from Brockworth to Wotton has been considered to indicate a Severn crossing at Kingsholm one Km north of Gloucester, where, as late as the seventeenth century, a major branch of the river flowed slightly west of modern Kingsholm. The extent of early Roman archaeological material from Kingsholm makes it likely to have been a military site early in the Roman period. (l) Between Wotton Hill and Kingsholm this presumed line is lost; the road possibly passed through the grounds of Hillfield House and along the ridge, now marked by Denmark Road, towards the river. -

Disciplinary Culture

Disciplinary Culture: Artillery, Sound, and Science in Woolwich, 1800–1850 Simon Werrett This article explores connections between science, music, and the military in London in the first decades of the nineteenth century.1 Rather than look for applications of music or sound in war, it considers some techniques common to these fields, exemplified in practices involving the pendulum as an instrument of regulation. The article begins by exploring the rise of military music in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and then compares elements of this musical culture to scientific transformations during 1 For broad relations between music and science in this period, see: Myles Jackson, Harmonious Triads: Physicians, Musicians, and Instrument Makers in Nineteenth-Century Germany (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006); Alexandra Hui, The Psychophysical Ear: Musical Experiments, Experimental Sounds, 1840–1910 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012); Emily I. Dolan and John Tresch, “‘A Sublime Invasion’: Meyerbeer, Balzac, and the Opera Machine,” Opera Quarterly 27 (2011), 4–31; Emily Thompson, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900–1933 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004). On science and war in the Napoleonic period, see for example: Simon Werrett, “William Congreve’s Rational Rockets,” Notes & Records of the Royal Society 63 (2009), 35–56; on sound as a weapon, Roland Wittje, “The Electrical Imagination: Sound Analogies, Equivalent Circuits, and the Rise of Electroacoustics, 1863–1939,” Osiris 28 (2013), 40–63, here 55; Cyrus C. M. Mody, “Conversions: Sound and Sight, Military and Civilian,” in The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies, eds. Trevor Pinch and Karin Bijsterveld (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

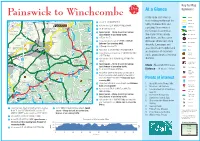

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

Secondary and FE Teacher Resource for Teaching Key Stages 3–5 Sculpture in the RA Collection a Sculpture Student at Work in the RA Schools in 1953

Secondary and FE Teacher Resource For teaching key stages 3–5 Sculpture in the RA Collection A sculpture student at work in the RA Schools in 1953. © Estate of Russell Westwood Contents Introduction Illustrated key works with information, quotes, key words, questions, useful links and art activities for the classroom Glossary Further reading To book your visit Email studentgroups@ royalacademy.org.uk or call 020 7300 5995 roy.ac/teachers ‘...we live in a world where images are in abundance and they’re moving, [...] they’re doing all kinds of things, very speedily. Whereas sculpture needs to be given time, you need to just wait with it and become the moving object that it isn’t, so this action between the still and the moving is incredibly demanding for all. ’ Phyllida Barlow RA The Council of the Royal Academy selecting Pictures for the Exhibition, 1875, Russel Cope RA (1876). Photo: John Hammond Introduction What is the Royal Academy of Arts? The Royal Academy (RA) was Every newly elected Royal set up in 1768 and 2018 was Academician donates a work of art, its 250th anniversary. A group of known as a ‘Diploma Work’, to the artists and architects called Royal RA Collection and in return receives Academicians (or RAs) are in charge a Diploma signed by the Queen. The of governing the Academy. artist is now an Academician, an important new voice for the future of There are a maximum of 80 RAs the Academy. at any one time, and spaces for new Members only come up when In 1769, the RA Schools was an existing RA becomes a Senior founded as a school of fine art. -

Bon Voyage? 250 Years Exploring the Natural World SHNH Summer

Bon Voyage? 250 Years Exploring the Natural World SHNH summer meeting and AGM in association with the BOC World Museum Liverpool Thursday 14th and Friday 15th June 2018 Abstracts Thursday 14th June Jordan Goodman, Department of Science and Technology Studies, University College London In the Wake of Cook? Joseph Banks and His ‘Favorite Projects’ James Cook’s three Pacific voyages spanned the years from 1768 to 1780. These were the first British voyages of exploration in which natural history collecting formed an integral part. Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander were responsible for the collection on the first voyage, HMS Endeavour, between 1768 and 1771; Johann and Georg Forster, collected on the second voyage, HMS Resolution, between 1772 and 1775; and David Nelson continued the tradition on the third voyage, HMS Resolution, from 1776 to 1780. Though Cook’s first voyage brought Banks immense fame, it was the third voyage that initiated a new kind of botanical collecting which he practised for the rest of his life. He called it his ‘Favorite Project’, and it consisted of supplying the royal garden at Kew with living plants from across the globe, to make it the finest botanical collection in the world. Banks appointed David Nelson, a Kew gardener, to collect on Cook’s third voyage. Not only would the King’s garden benefit from a supply of exotic living plants, but the gardeners Banks sent out to collect them would also learn how best to keep the plants alive at sea, for long periods of time and through many different climatic conditions. -

“A Valuable Monument of Mathematical Genius”\Thanksmark T1: the Ladies' Diary (1704–1840)

Historia Mathematica 36 (2009) 10–47 www.elsevier.com/locate/yhmat “A valuable monument of mathematical genius” ✩: The Ladies’ Diary (1704–1840) Joe Albree ∗, Scott H. Brown Auburn University, Montgomery, USA Available online 24 December 2008 Abstract Our purpose is to view the mathematical contribution of The Ladies’ Diary as a whole. We shall range from the state of mathe- matics in England at the beginning of the 18th century to the transformations of the mathematics that was published in The Diary over 134 years, including the leading role The Ladies’ Diary played in the early development of British mathematics periodicals, to finally an account of how progress in mathematics and its journals began to overtake The Diary in Victorian Britain. © 2008 Published by Elsevier Inc. Résumé Notre but est de voir la contribution mathématique du Journal de Lady en masse. Nous varierons de l’état de mathématiques en Angleterre au début du dix-huitième siècle aux transformations des mathématiques qui a été publié dans le Journal plus de 134 ans, en incluant le principal rôle le Journal de Lady joué dans le premier développement de périodiques de mathématiques britanniques, à finalement un compte de comment le progrès dans les mathématiques et ses journaux a commencé à dépasser le Journal dans l’Homme de l’époque victorienne la Grande-Bretagne. © 2008 Published by Elsevier Inc. Keywords: 18th century; 19th century; Other institutions and academies; Bibliographic studies 1. Introduction Arithmetical Questions are as entertaining and delightful as any other Subject whatever, they are no other than Enigmas, to be solved by Numbers; . -

The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): an Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2003 The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment Terrance Gerard Galvin University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Architecture Commons, European History Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Galvin, Terrance Gerard, "The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment" (2003). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 996. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/996 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/996 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Architecture of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771-1843) and Sir John Soane (1753-1837): An Exploration Into the Masonic and Occult Imagination of the Late Enlightenment Abstract In examining select works of English architects Joseph Michael Gandy and Sir John Soane, this dissertation is intended to bring to light several important parallels between architectural theory and freemasonry during the late Enlightenment. Both architects developed architectural theories regarding the universal origins of architecture in an attempt to establish order as well as transcend the emerging historicism of the early nineteenth century. There are strong parallels between Soane's use of architectural narrative and his discussion of architectural 'model' in relation to Gandy's understanding of 'trans-historical' architecture. The primary textual sources discussed in this thesis include Soane's Lectures on Architecture, delivered at the Royal Academy from 1809 to 1836, and Gandy's unpublished treatise entitled the Art, Philosophy, and Science of Architecture, circa 1826. -

Square Pegges and Round Robins: Some Mid-Eighteenth Century Numismatic Disputes

SQUARE PEGGES AND ROUND ROBINS: SOME MID-EIGHTEENTH CENTURY NUMISMATIC DISPUTES H.E. MANVILLE BRITISH Numismatics as a science may fairly be said to have come of age in the mid-eighteenth century with early discussions among antiquarians groping toward solu- tions to some of the more vexatious questions: Who struck the ancient British coins dug up throughout southern England and what was the meaning of the brief inscriptions on some of them? Did the Anglo-Saxons coin any gold? Where were the coins of Richard I and King John? How could one differentiate the coins of William I and II; Henry II and III; Edwards I to III; and Henry IV to the early issue of Henry VII? The debates over these and other problems ranged well into the next century but gradually the path toward historical solutions grew clearer - although not without false turns and dead ends. We shall take a brief look at two of these questions and another that sprang full-blown from a flan split on a single coin and the over-fertile imagination of several mid-century antiquaries. Numismatic studies in the first quarter of the eighteenth century attempted to sort out some of the earliest English issues, as in the Numismata Anglo-Saxonica et Anglo-Danica illustrata of Sir Andrew Fountaine, printed in the Thesaurus of Dr George Hickes in 1705;1 and in Notae in Anglo-Saxonum nummos, published anonymously by Edward Thwaites in 1708.2 A chapter in Ducatus Leodiensis by Ralph Thoresby, first published in 1715, discussed coins in his private collection and was frequently referred to by other writers.3 With the Historical Account of English Money by Stephen Martin Leake, first published anonymously in 1726, a handbook solely on the coins from the Conquest became available.4 Although its original eight octavo plates illustrate fewer than seventy coins to the Restoration, Leake's work lasted through the century - later editions of 1745 and 1793 bringing it up-to-date and including additional plates.