Agriculture and Food Indicators Group, 2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRING 2010 Land O’Lakes Tourism Association - by Ken Hook, LOLTA

Regional Green Vision & Strategy Project SPRING By Anne Marie Young, County of Frontenac Local municipal and economic development organizations have joined forces to create a regional green vision and strategy that founding partners expect will position the Kingston- Frontenac-Lennox and Addington area as a global leader in energy and the environment. Frontenac County, the Kingston Area Economic Development Corporation, and the Frontenac Community Futures Development Corporation secured $60,000 from the Frontenac CFDC through the Eastern Ontario Development Program (EODP) and launched a Regional Green Vision and Strategy project to move the region forward on this front. The idea of building a regional effort emerged from a workshop held in Kingston in the spring of 2009, participants looked at the wind turbines then going up on Wolfe Island, the sustain- ability plans coming forward in Frontenac County and the City of Kingston, research taking place at our post-secondary education institutions, the development of a solar farm nearby, the continued development of SWITCH, and many other ‘green’ developments. It was realized that the region has the critical mass to become known as a green region and there is reason to capitalize on the opportunity. The Regional Green Vision and Strategy project is focused on bringing the region’s stake- holders together in a shared effort to establish awareness of this critical mass, attract attention outside the region, and encourage further activity within the region. Early in 2010, additional stakeholders will be invited and encouraged to become part of the green initiative. Looking for a New Business Opportunity? The Frontenac Stewardship Council, through Eastern Ontario Development funding from the Frontenac CFDC, is developing a business plan that explores the feasibility of a local busi- ness providing septic haulage from ‘water-access only’ properties in Frontenac County. -

Frogpond 35.1 • Winter 2012

frogpond The Journal of the Haiku Society of America fr g Volume 35, Number 1 Winter, 2012 About HSA & Frogpond Subscription / HSA Membership: In the USA: adults $35; seniors (65+) & students (full-time) $30. In Canada and Mexico: $37; seniors & students $32. For all others: 47 USD. Payment by check on a USA bank or by In- ternational Postal Money Order. All subscriptions/memberships are annual, expire on December 31, and include three issues of Frogpond as well as three newsletters and voting rights. All correspondence regarding new and renewed memberships should be directed to the HSA Secretary (see p. 186). Make checks and money orders payable to Haiku Society of America, Inc. Single copies of back issues postpaid: In USA & Canada, $12; elsewhere, $15 seamail; $20 airmail. These prices are for recent issues. Older ones might cost more, depending on how many are left. Please enquire first. Make checks payable to Haiku Society of America, Inc. Send all orders to the Frogpond Edi- tor (see next page). Changes of Address and Requests for Information: Such concerns should be directed to the HSA Secretary (see p. 186). Contributor Copyright and Acknowledgments: All prior copyrights are retained by contributors. Full rights revert to contributors upon publication in Frogpond. Neither the Haiku Society of America, its officers, nor the editor assume responsibility for views of contributors (including its own officers) whose work is printed in Frogpond, research errors, infringement of copyrights, or failure to make proper acknowledgments. Frogpond Listing and Copyright Information: ISSN 8755-156X Listed in the MLA International Bibliography and Humanities Inter- national Complete © 2012 by the Haiku Society of America, Inc. -

Celebrating Sustainability

Get me every issue Become a member! InsiderVolume 32, Number 1 • January–March 2017 Finding Balance Through Retreat: Wintergreen to carry out strategic plan- by Rena Upitis ning. The simple yet comfort- able accommodations include i n t e r g r e e n private rooms, shared rooms, Studios is a year- woodland cabins, and tent spac- round wilderness es for those who prefer to sleep retreat centre. under the stars. WThe built facilities are nestled Guests can explore more than within more than 200 acres of a dozen trails through the proper- forests, marshes, and meadows ty, including guided hikes. There in the heart of the Frontenac are mixed forests and meadows, Arch Biosphere Reserve. ponds and marshes, spectacular This reserve is one of a glob- granite outcroppings, and a gla- al network of UNESCO desig- cier-carved lake. nated reserves, unique natural The hosts serve bountiful regions populated with people meals, featuring local and organ- committed to sustainable com- ic ingredients, much of which is munity living and development. grown in gardens on site. There Located in the Township of are always vegetarian, gluten- South Frontenac, Wintergreen free, and vegan options, and is near the town of Westport, Wintergreen serves responsibly Ontario. sourced fish, and local poultry, Workshops in the arts, educa- pork, goat, and beef. tion, and environmental studies Wintergreen is a not-for- are held in an inviting solar- profit charitable organization, powered lodge. The building incorporated in 2007. The straw- serves both as a demonstration bale lodge was built in 2008 site and a research site for off- and workshops began that fall. -

The Parthenon Cabin Guide

www.wintergreenstudios.com | 613.273.8745 | [email protected] THE PARTHENON CABIN GUIDELINES www.wintergreenstudios.com | 613.273.8745 | [email protected] ABOUT THE PARTHENON The Parthenon is exquisitely primitive, located about 25 minutes from the main parking lot at Wintergreen. By 25 minutes we mean by foot! The hike is rugged in places, so pack as lightly as possible. There is no electricity or running water—but it is warm and cozy and the views of the marsh are lovely. Why is it called the Parthenon, you might be asking? Well, it started as a joke when someone quipped that since we were carrying in beautiful architectural salvage for the porch, along with bags and bags of concrete for the foundation, why not just carry in marble and make it out of stone? And so the “Parthenon” was born. (When the founder’s daughter was 4 years old, she asked why everyone laughed when they learned the cabin was called the Parthenon. When she was shown a photo of the Parthenon in Greece, she responded with, “My Mama’s Parthenon is better. It has a roof.”) The Parthenon is well-equipped with everything you should need for a few days/nights of “glamping”: a futon double bed (with fresh sheets), a table, a kitchen station with cooking essentials, and plenty of sanitizing wipes. There is a chamber pot in the cabin as well as a thunderbox overlooking the lake (well stocked with toilet paper), and a cooler for outdoor food storage (no ice). We recommend bringing ice packs to keep your food cool in the warmer months. -

Cattails May 2014 Edition

cattails May 2014 Edition cattails May 2014 ________________________________________________________________________ Contents UHTS Main Website • Editor's Prelude • Contributors • Haiku Pages • Haibun Pages • Haiga-Tankart • Senryu Pages • Tanka Pages • Translations-Amelia Fielden • Youth Corner Pages • UHTS Contests • Pen this Painting • Book Review Pages • Featured Artist-Ron Moss • Featured Poet-Joe McKeon • Also, there are many other pages on the UHTS Main Website that are "not" included here in cattails, so, if you are looking for What to submit, or How to submit, How to Join, How to Donate, or wanting to see the Seedpods News Bulletin, know about the UHTS Officers and Support Team, visit Archives see our Members List, Omnibus details, the Calendar, and other information, please revisit the UHTS Main Website NOTE: This PDF version of the Premier Issue of cattails does not include the majority of the haiga, tankart illustrations, or other photos. These files could not be found in the old UHTS website backups made before we moved to the new UHTS website Copyright © 2014 and 2017 all authors and artists cattails May 2014 Edition cattails May 2014 Principal Editor's Prelude ____________________________________________________________ Happy International Haiku/Senryu Month from the UHTS As usual, before I begin, let me say that we are only human and do our very best, but if perchance you do not see your accepted work here, or if you didn't receive a timely response when you submitted work, please don’t hesitate to contact us right away. We receive submissions in the thousands, and emails do occasionally go awry. However, being online (rather than in-print) allows us to easily and quickly correct any errata. -

Promoting Environmental Stewardship Through Gardens: a Case Study Of

Promoting Environmental Stewardship through Gardens: A Case Study of Children’s Views of an Urban School Garden Program RENA UPITIS SCOTT HUGHES ANNA PETERSON Queen’s University This story contains a swear word. A word that makes its way into everyday conversation. Its use is completely taboo in schools—especially elementary schools. This word, used to add dramatic emphasis to an important point, is the F-bomb oF swear words: fucking. As in, “Don’t touch that fucking fence.” A group oF high school students was hanging out one evening in the yard oF a local public elementary school. The students came upon a small Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies Volume 11 Number 1, 2013 Promoting Environmental Stewardship Through Gardens UPITIS, HUGHES, & PETERSON wooden Fence protecting a garden bed From potential damage during busy school day play times. The Fence was starting to rot, so the boys decided that they would tear away at it and bash it down, muttering, “Let’s trash that Fucking Fence.” The one boy—overheard by one of the parents at the school—stopped his Friends From the destruction by his strong directive: “I built that Fucking Fence. Leave it alone.” The parent who witnessed the near destruction oF the Fence was actively involved in the school garden program at the elementary school in question. The parent shared this story to explain how children’s direct experiences with the school garden—in this case, building a Fence to protect vegetables growing in a garden bed—promote their sense oF ownership towards their school and their sense of stewardship towards the environment. -

The Blue Bill Volume 66 Number 4

The Blue Bill Quarterly Journal of the Kingston Field Naturalists ISSN 0382-5655 Volume 66, No. 4 December 2019 Contents 1 President’s Preliminaries / Anthony Kaduck 153 2 Kingston Region Birds – Summer 2019 (Jun 1st – July 31st)/ Mark D. Read 154 3 Fall Round-up – November 1 to 3, 2019 / Erwin Batalla 157 4 Odonata List & Yearly Sightings 2019 / Al Quinsey 162 5 Kingston Buerfly Summary for 2019 / John Poland 168 6 Articles 172 6.1 Wildlife Photography Tips #2 / Anthony Kaduck ............................ 172 6.2 Great Bear Rainforest Adventure (August 17 -24, 2019) / Janis Grant ................ 176 6.3 Exploring the Backyard / Carolyn Bonta ................................ 178 6.4 A Look below the Surface of a Lake / Shirley French ......................... 179 7 KFN Outings 182 8 Clipped Classics 197 9 Reader Contributions 198 2018/2019 Executive President . Anthony Kaduck The Blue Bill is the quarterly Honorary President . Ron Weir journal (published March, June, September and De- Vice-President (Speakers) . Kenneth Edwards cember) of the Kingston Past President . Alexandra Simmons Field Naturalists, P.O. Box 831, Kingston ON, K7L 4X6, Treasurer . Larry McCurdy Canada. Recording Secretary . Janis Grant kingstonfieldnaturalists.org Membership Secretary . .Kathy Webb Send submissions to the editor Archives . Peter McIntyre by the 5th of the month of pub- lication (i.e. the 5th of March, Bird Records/Sightings/Ontbirds . .Mark Read June, September, or December) Book Auction . .Janet and Bruce Ellio to [email protected] Conservation . .Chris Hargreaves Editor of The Blue Bill . Peter Waycik Submissions may be in any format. Equations should be in Education . Shirley French LATEX. Please provide captions and credit information for pho- Facebook Coordinator . -

Full Authority Board Meeting Agenda

Full Authority Board Meeting Agenda Date: Wednesday, March 24, 2021 Time: 6:45 p.m. Location: Microsoft Teams 1. Roll Call 2. Adoption of Agenda A. That the agenda Be Adopted as circulated. 3. Declaration of Conflict of Interest 4. Delegation / Presentation 4.1. Holly Evans, Watershed Planning Coordinator ➢ Presentation – Little Cataraqui Creek Habitat Compensation Project B. That Cataraqui Conservation Full Authority Board Receive the presentation by Holly Evans, Watershed Planning Coordinator on Little Cataraqui Creek Habitat Compensation Project. 1 Page 2 of 5 Cataraqui Conservation - Full Authority Board Meeting Agenda March 24, 2021 – Microsoft Teams 4.2. Krista Fazackerley, Supervisor, Communications & Education ➢ Presentation – New Cataraqui Conservation Website C. That Cataraqui Conservation Full Authority Board Receive the presentation by Krista Fazackerley, Supervisor, Communications & Education on the new Cataraqui Conservation website. 5. Approval of Previous Minutes 5.1. Minutes of the Cataraqui Conservation Full Authority Board Meeting of February 24, 2021 D. That the minutes of the Cataraqui Conservation Full Authority Board meeting of February 24, 2021, Be Approved. 5.2. Minutes of the Cataraqui Conservation Full Authority Board Special meeting of March 10, 2021 E. That the minutes of the Cataraqui Conservation Full Authority Special Board meeting of March 10, 2021, Be Approved. 6. Business Arising 7. Items for Consideration 7.1. Little Cataraqui Creek Habitat Compensation Project (PR 00292) (report IR- 026-21) F. That Report IR-026-21, Little Cataraqui Creek Habitat Compensation Project (PR 00292), Be Received. 2 Page 3 of 5 Cataraqui Conservation - Full Authority Board Meeting Agenda March 24, 2021 – Microsoft Teams 7.2. Changes to the Conservation Authorities Act (report IR-027-21) G. -

Council Meeting Agenda

Page 1 of 187 TOWNSHIP OF SOUTH FRONTENAC COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA TIME: 6:00 PM, DATE: Tuesday, May 7, 2019 PLACE: Council Chambers. 1. Call to Order a) Resolution 2. Declaration of pecuniary interest and the general nature thereof 3. Approval of Agenda 4. Scheduled Closed Session a) Section 239.2 (d) Labour Relations and Employee Negotiations & Approve Minutes b) Minutes of Closed Session meetings held March 19 and April 16, 2019 c) Labour Relations and Employee Negotiations 5. ***Recess - reconvene at 7:00 p.m. for Open Session 6. Rise & Report from Closed Session 7. Delegations a) Brenda Crawford, Harrowsmith Beautification Committee, re: 3 - 6 Proposed plans and projects 8. Public Meeting - n/a 9. Approval of Minutes a) April 16, 2019 Council Meeting 7 - 13 10. Business Arising from the Minutes 11. Reports Requiring Action a) Appointment of Building Inspector (See By-law 2019-27) 14 b) Retirement/Auxiliary Firefighter Policy and Job Description 15 - 18 c) Strategic Planning - Next Steps 19 - 20 d) Women's Institute - Centennial Celebration 21 - 22 e) ICIP Funding 23 Page 2 of 187 f) Regional Roads - Overview and Background Report 24 - 43 g) Waste Management in Frontenac County - Options for the Future 44 - 152 12. Committee Meeting Minutes a) Heritage Committee meeting held November 26, 2018 153 - 154 b) Loughborough District Canada Day Committee meeting held March 155 - 27, 2019 156 c) Development Services Committee meeting held March 25, 2019 157 - 162 d) Harrowsmith Beautification Committee meeting held April 3, 2019 163 e) Bedford District Recreation Committee meeting held April 23, 2019 164 - 165 13. -

Frogpond 34.3 • Autumn 2011

frogpond The Journal of the Haiku Society of America fr g Volume 34, Number 3 Fall, 2011 About HSA & Frogpond Subscription / HSA Membership: For adults in the USA & Canada, 33 USD; for seniors and students in the USA & Canada, 30 USD; for everyone elsewhere, 45 USD. Pay by check on a USA bank or by International Postal Money Order. All subscriptions/memberships are annual, expiring on December 31, and include three issues of Frogpond as well as three newsletters and voting rights. All correspondence regarding new and renewed memberships should be directed to the HSA Secretary (see the list of officers, p. 123). Make checks and money orders payable to Haiku Society of America, Inc. Single copies of back issues: For USA & Canada, 12 USD; for elsewhere, 15 USD by surface and 20 USD by airmail. Older issues might cost more, depending on how many are left. Please enquire first. Make checks payable to Haiku Society of America, Inc. Send single copy and back issue orders to the Frogpond Editor (see next page). Changes of Address and Requests for Information: Such concerns should be directed to the HSA Secretary (see p. 123). Contributor Copyright and Acknowledgments: All prior copyrights are retained by contributors. Full rights revert to contributors upon publication in Frogpond. Neither the Haiku Society of America, its officers, nor the editor assume responsibility for views of contributors (including its own officers) whose work is printed in Frogpond, research errors, infringement of copyrights, or failure to make proper acknowledgments. Frogpond Listing and Copyright Information: ISSN 8755-156X Llisted in the MLA International Bibliography, Humanities Interna- tional Complete, Poets and Writers. -

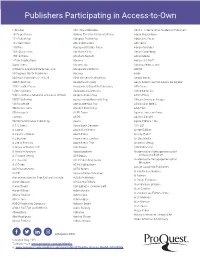

Publishers Participating in Access-To-Own

Publishers Participating in Access-to-Own Publisher ABG-Aqua Ediciones Adjuris - International Academic Publishers 10 Finger Press Abilene Christian University Press Adora Productions 111 Publishing Abington Publishing Adrenaline Press 12 Pines Press ABK Publications Adri Nerja 120 Pies Aboriginal Studies Press Adrián Gonzalez 13th Story Press Abraham Failla Adrian Greenberg 180° éditions Abraham Satoshi Adrian Melon 1-Take Publications Abrams Adriana LS Swift 2Leaf Press Abrams, Inc. Adriano Pereira Lima 3 Dreams Creative Enterprises, LLC Abrapalabra Editorial AECEP 30 Degrees South Publishers Abrasce Aedis 30 South Publishers (PTY) Ltd ABW Wissenschaftsverlag Aerilyn Books 306 Publishing Academia-Bruylant Aeryn Anders, Gerson Loyola De Aguilar 45th Parallel Press Academic & Scientific Publishers AFB Press 5 Sens Editions Acao Social Claretiana Aferre Editor S.L. 5 Sens Editions, Madame Anne-Lise Wittwer Acapella Publishing Affirm Press 5050 Publishing acasa Immobilienmarketing African American Images 50Minuten.de Ace Academics, Inc. African Sun Media 50Minutes.com Açedrex Publishing AGA/FAO 50Minutes.fr ACER Press Against the Grain Press 7Letras ACOG Agatha Albright 80/20 Performance Publishing Acoria Agora, Editora, Ltda A C U Press Acorn Book Services AIATSIS A capela Acorn Guild Press Aimee Sullivan A cigarra - eBooks Acorn Press Ainsley Quest A L Butcher Acorn Press, Limited Air Sea Media A Life In Print Inc Acorn Press, The Aisthesis Verlag A Sense of Nature LLC Acre Books AJR Publishing A Verba Futurorum Acrodacrolivres Akademische -

Decatur Haiku Collection at Millikin University

Haiku & Tanka Books and Journals: a Bibliography of Publications in the Decatur Haiku Collection Last updated: August 25, 2021 © 2021, Randy Brooks These print publications are available to students enrolled in courses at Millikin University for research on haiku, tanka, senryu and related haikai arts. If you have print haiku publications or collections you would like to donate to the Decatur Haiku Collection, please send them to: Dr. Randy Brooks Millikin University 1184 West Main Decatur, Illinois 62522 [email protected] Author, First Name. Title of the Book. Place: Publisher, date. Author, First Name. Translator. Title of the Book. Place: Publisher, date. Abbasi, Saeed. My Haiku. Toronto: Abbasi Studio, 2012. Abe, Ryan. Golden Sunrises . A Narrative in Haiku. San Mateo, CA, 1973. Addiss, Stephen. The Art of Haiku: Its History Through Poems and Paintings of the Japanese Masters. Boston & London: Shambala, 2012. Addiss, Stephen. Cloud Calligraphy. Winchester, VA: Red Moon Press, 2010. Addiss, Stephen. Haiga: Takebe Socho and the Haiku-Painting Tradition. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1995. Addiss, Stephen. A Haiku Garden: The Four Seasons in Poems and Prints. New York: Weatherhill Press, 1996. Addiss, Stephen. Haiku Humor: Wit and Folly in Japanese Poems and Prints. New York: Weatherhill Press, 2007. Addiss, Stephen. Haiku Landscapes: In Sun, Wind, Rain, and Snow. New York: Weatherhill Press, 2002. Addiss, Stephen. A Haiku Menagerie: Living Creatures in Poems and Prints. New York: Weatherhill Press, 1992. Addiss, Stephen. Haiku People: Big and Small in Poems and Prints. New York: Weatherhill Press, 1998. Addiss, Stephen, Kris Kondo & Lidia Rozmus. Sumi-e Show: July 8-11, 1999 Northwestern University.