The Secret River.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Sydney Theatre Award Nominations

2015 SYDNEY THEATRE AWARD NOMINATIONS MAINSTAGE BEST MAINSTAGE PRODUCTION Endgame (Sydney Theatre Company) Ivanov (Belvoir) The Present (Sydney Theatre Company) Suddenly Last Summer (Sydney Theatre Company) The Wizard of Oz (Belvoir) BEST DIRECTION Eamon Flack (Ivanov) Andrew Upton (Endgame) Kip Williams (Love and Information) Kip Williams (Suddenly Last Summer) BEST ACTRESS IN A LEADING ROLE Paula Arundell (The Bleeding Tree) Cate Blanchett (The Present) Jacqueline McKenzie (Orlando) Eryn Jean Norvill (Suddenly Last Summer) BEST ACTOR IN A LEADING ROLE Colin Friels (Mortido) Ewen Leslie (Ivanov) Josh McConville (Hamlet) Hugo Weaving (Endgame) BEST ACTRESS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Blazey Best (Ivanov) Jacqueline McKenzie (The Present) Susan Prior (The Present) Helen Thomson (Ivanov) BEST ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Matthew Backer (The Tempest) John Bell (Ivanov) John Howard (Ivanov) Barry Otto (Seventeen) BEST STAGE DESIGN Alice Babidge (Suddenly Last Summer) Marg Horwell (La Traviata) Renée Mulder (The Bleeding Tree) Nick Schlieper (Endgame) BEST COSTUME DESIGN Alice Babidge (Mother Courage and her Children) Alice Babidge (Suddenly Last Summer) Alicia Clements (After Dinner) Marg Horwell (La Traviata) BEST LIGHTING DESIGN Paul Jackson (Love and Information) Nick Schlieper (Endgame) Nick Schlieper (King Lear) Emma Valente (The Wizard of Oz) BEST SCORE OR SOUND DESIGN Stefan Gregory (Suddenly Last Summer) Max Lyandvert (Endgame) Max Lyandvert (The Wizard of Oz) The Sweats (Love and Information) INDEPENDENT BEST INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION Cock (Red -

Book Club Sets

Book Club Sets Alexander, Todd Thirty thousand bottles of wine and a pig called Helga Australian Non-Fiction Sharply observed, funny and poignant, a tree-change story with a twist. Once I was the poster boy for corporate success, but now I’m crashing through the bush in a storm in search of a missing pig. How the hell did we end up here? Todd and Jeff have had enough of the city. Sick of the daily grind and workaday corporate shenanigans, they throw caution to the wind and buy 100 acres in the renowned Hunter Valley wine region, intent on living a golden bucolic life and building a fabulous B&B, where they can offer the joys of country life to heart-weary souls. Todd will cook, Jeff will renovate. They have a vineyard, they can make wine. They have space, they can grow their own food. They have everything they need to make their dreams come true. How hard can it be? (288 pages) Alexandra, Belinda The Invitation Australian Fiction - Historical Sometimes the ties that bind are the most dangerous of all. Paris, 1899. Emma Lacasse has been estranged from her older sister for nearly twenty years, since Caroline married a wealthy American and left France. So when Emma receives a request from Caroline to meet her, she is intrigued. Caroline invites Emma to visit her in New York, on one condition: Emma must tutor her shy, young niece, Isadora, and help her prepare for her society debut. Caroline lives a life of unimaginable excess and opulence as one of New York's Gilded Age millionaires and Emma is soon immersed in a world of luxury beyond her wildest dreams - a far cry from her bohemian lifestyle as a harpist and writer with her lover, Claude, in Montmartre. -

Australian Women's Book Review

Australian Women's Book Review Volume 19.1 (2007) ”May Day in Istanbul with Amazonâ” - Eileen Haley Editor: Carole Ferrier Associate Editor: Maryanne Dever Editorial Advisory Board: Brigid Rooney, Margaret Henderson, Barbara Brook, Nicole Moore, Bronwen Levy, Susan Carson, Shirley Tucker ISSN : 1033 9434 1 Contents 4. Mapping By Jena Woodhouse 6. Digging Deep Kathleen Mary Fallon Paydirt . Crawley: UWA Press, 2007. Reviewed by Alison Bartlett 10. Translating Lives Mary Besemeres and Anna Wierzbicka (Eds). Translating Lives: Living with Two Languages and Cultures. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 2007. Reviewed by Kate Stevens 13. Modes of Connection Gail Jones. Sorry . Vintage, 2007. Reviewed by Angela Meyer 16. Hybrid Histories Peta Stephenson, The Outsiders Within: Telling Australia's Indigenous–Asian Story . Sydney : University of New South Wales Press, 2007; Sally Bin Demin, Once in Broome . Broome: Magabala Books, 2007. Reviewed by Fiona McKean 19. Journey Through Murky Water Kate Grenville, Searching for the Secret River . Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2006. Reviewed by Shannon Breen 21. Lifting History's Veil Kim Wilkins. Rosa and the Veil of Gold . HarperCollins, 2005 Reviewed by Elise Croft 23. Sequined Hearts and Ostrich Feathers: Tales from Tightropes of Life Stephanie Green, Too Much, Too Soon . Pandanus Books: Canberra, 2006. Catherine Rey, The Spruiker's Tale. First published under the title, Ce que racontait Jones. Paris, 2003. Giramondo Publishing Company: University of Western Sydney, 2005. Reviewed by Misbah Khokhar 26. There's No Business Like Dough Business Roberta Perkins and Frances Lovejoy. Call Girls: Private Sex Workers in Australia . University of Western Australia Press, 2007. Reviewed by Fiona Bucknall 29. -

2018 Brochure Web.Pdf

SEASON 2018 2 A message from Kip Williams 5 The top benefits of a Season Ticket 10 Insight Events 13 Get the most out of your Season Ticket THE PLAYS 16 Top Girls 18 Lethal Indifference 20 Black is the New White 22 The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui 24 Going Down 26 The Children 28 Still Point Turning: The Catherine McGregor Story 30 Blackie Blackie Brown 32 Saint Joan 34 The Long Forgotten Dream 36 The Harp in the South: Part One and Part Two 40 Accidental Death of an Anarchist 42 A Cheery Soul SPECIAL OFFERS 46 Hamlet: Prince of Skidmark 48 The Wharf Revue 2018 HOW TO BOOK AND USEFUL INFO 52 Let us help you choose 55 How to book your Season Ticket 56 Ticket prices 58 Venues and access 59 Dates for your diary 60 Walsh Bay Kitchen 61 The Theatre Bar at the End of the Wharf 62 The Wharf Renewal Project 63 Support us 64 Thank you 66 Our community 67 Partners 68 Contact details 1 A MESSAGE FROM KIP WILLIAMS STC is a company that means a lot to me. And, finally, I’ve thought about what theatre means to me, and how best I can share with It’s the company where, as a young teen, I was you the great passion and love I have for this inspired by my first experience of professional art form. It’s at the theatre where I’ve had some theatre. It’s the company that gave me my very of the most transformative experiences of my first job out of drama school. -

A Study Guide by Marguerite O'hara

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY MARGUERITE O’HARA http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-586-5 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 CLICK ON THE ABOVE BUTTONS TO JUMP TO THE DIFFERENT SECTIONS IN THE PDF William Thornhill is driven by an oppressed, impoverished past and a desperate need to provide a safe home for his beloved family in a strange, foreboding land. The Secret River is an epic tragedy in which a good man is compelled by desperation, fear, ambition and love for his family to par- ticipate in a crime against humanity. It allows an audience, two hundred years later, to have a personal insight into the troubled heart of this nation’s foundation story. There are two eighty minute episodes that tell the story of one of the ultimately tragic wars between colonists and the country’s original inhabitants. The ongoing effects result- ing from these early conflicts over land still resonate today, more than 200 years on from this story. Who owns the land and who has the right to use it, develop it and protect it? A brief preview of the series can be viewed at: http://abc. net.au/tv/programs/secret-river/ Advice to teachers Both the novel and this miniseries contain some quite graphic scenes of violence, including a depiction of a flog- ging and scenes of the violence inflicted on people during the conflict between the settlers and the Aboriginals. Teachers are advised to preview the material (particularly Episode 2) before showing it to middle school students, even though it might seem to fit well into middle school Australian History. -

Chloe Armstrong

JOSH MCCONVILLE | Actor FILM Year Production / Character Director Company 2017 1% Stephen McCallum Head Gear Films Skink 2016 WAR MACHINE David Michôd Porchlight Films Payne 2015 JOE CINQUE'S CONSOLATION Sotiris Dounoukos Consolation Productions Chris 2014 DOWN UNDER Abe Forsythe Riot Films Gav 2013 THE INFINITE MAN Hugh Sullivan Infinite Man Productions P/L Dean Trilby 2012 THE TURNING “COMMISSION” David Wenham ArenaMedia Vic Lang TELEVISION Year Production/Character Director Company 2017 HOME & AWAY Various Seven Network Caleb 2015 CLEVERMAN Wayne Blair ABCTV Dickson 2013 THE KILLING FIELD Samantha Lang Seven Network Operations Jackson 2012 REDFERN NOW Various ABC TV/Blackfella Films Photographer Shanahan Management Pty Ltd Level 3 | Berman House | 91 Campbell Street | Surry Hills NSW 2010 PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] 2011 WILD BOYS Various Southern Star Productions No. 8 Ben 2009 UNDERBELLY II: Various Screentime A TALE OF TWO CITIES Hurley THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2017 CLOUD 9 Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Clive/Cathy 2016 A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Bottom 2016 ALL MY SONS Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company George Deever 2016 HAY FEVER Imara Savage Sydney Theatre Company Sandy Tyrell 2016 ARCADIA Richard Cottrell Sydney Theatre Company Bernard Nightingale 2015 HAMLET Damien Ryan Bell Shakespeare Hamlet 2015 AFTER DINNER Imara Savage Sydney Theatre Company -

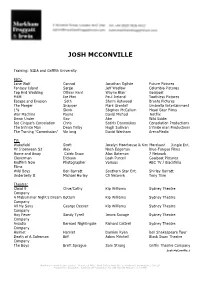

Josh Mcconville

JOSH MCCONVILLE Training: NIDA and Griffith University Film: Lone Wolf Conrad Jonathan Ogilvie Future Pictures Fantasy Island Sarge Jeff Wadlow Columbia Pictures Top End Wedding Officer Kent Wayne Blair Goalpost M4M Ice Man Paul Ireland Toothless Pictures Escape and Evasion Seth Storm Ashwood Bronte Pictures The Merger Snapper Mark Grentell Umbrella Entertainment 1% Skink Stephen McCallum Head Gear Films War Machine Payne David Michod Netflix Down Under Gav Abe Wild Eddie Joe Cinque's Consolation Chris Sotiris Dounoukos Consolation Productions The Infinite Man Dean Trilby Hugh Sullivan Infinite man Productions The Turning "Commission" Vic lang David Wenham ArenaMedia TV: Wakefield Scott Jocelyn Moorhouse & Kim Morduant Jungle Ent. Mr Inbetween S2 Alex Nash Edgerton Blue-Tongue Films Home and Away Caleb Snow Alan Bateman 7 Network Cleverman Dickson Leah Purcell Goalpost Pictures Redfern Now Photographer Various ABC TV / Blackfella Films Wild Boys Ben Barratt Southern Star Ent. Shirley Barratt Underbelly II Michael Hurley C9 Network Tony Tilse Theatre: Cloud 9 Clive/Cathy Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company A Midsummer Night's Dream Bottom Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company All My Sons George Deever Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Hay Fever Sandy Tyrell Imara Savage Sydney Theatre Company Arcadia Bernard Nightingale Richard Cottrell Sydney Theatre Company Hamlet Hamlet Damien Ryan Bell Shakespeare Tour Death of A Salesman Biff Adam Mitchell Black Swan Theatre Company The Boys Brett Sprague Sam Strong Griffin Theatre Company Josh McConville -

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report

2011 SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2 3 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT “I consider the three hours I spent on Saturday night … among the happiest of my theatregoing life.” Ben Brantley, The New York Times, on STC’s Uncle Vanya “I had never seen live theatre until I saw a production at STC. At first I was engrossed in the medium. but the more plays I saw, the more I understood their power. They started to shape the way I saw the world, the way I analysed social situations, the way I understood myself.” 2011 Youth Advisory Panel member “Every time I set foot on The Wharf at STC, I feel I’m HOME, and I’ve loved this company and this venue ever since Richard Wherrett showed me round the place when it was just a deserted, crumbling, rat-infested industrial pier sometime late 1970’s and a wonderful dream waiting to happen.” Jacki Weaver 4 5 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS THROUGH NUMBERS 10 8 1 writers under commission new Australian works and adaptations sold out season of Uncle Vanya at the presented across the Company in 2011 Kennedy Center in Washington DC A snapshot of the activity undertaken by STC in 2011 1,310 193 100,000 5 374 hours of theatre actors employed across the year litre rainwater tank installed under national and regional tours presented hours mentoring teachers in our School The Wharf Drama program 1,516 450,000 6 4 200 weeks of employment to actors in 2011 The number of people STC and ST resident actors home theatres people on the payroll each week attracted into the Walsh Bay precinct, driving tourism to NSW and Australia 6 7 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT Andrew Upton & Cate Blanchett time in German art and regular with STC – had a window of availability Resident Artists’ program again to embrace our culture. -

Molly Haydock

Molly Haydock Theresa Holtby Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Western Sydney University Acknowledgements Many thanks to my family and friends for their support and encouragement throughout this undertaking. I also wish to thank my supervisors, Anna Gibbs, Sara Knox and Carol Liston, for their direction and expertise. And to my husband, Derek Holtby, for gallons of tea, years of longsuffering, and generous help with all things technical, thank you. ii Statement of Authenticity The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original, except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. iii Table of Contents Abbreviations.......................................................................................................................................v Molly Haydock......................................................................................................................................1 Writing Molly...................................................................................................................................128 Preface..............................................................................................................................................129 1Introduction....................................................................................................................................130 Molly who?..................................................................................................................................132 -

2013 NIDA Annual Report

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF DRAMATIC ART THEATRE FILM TELEVISION 215 ANZAC PARADE KENSINGTON NSW 2033 POST NIDA UNSW SYDNEY NSW 2052 PHONE 02 9697 7600 2013 NIDA Annual Report FAX 02 9662 7415 EMAIL [email protected] ABN 99 000 257 741 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF DRAMATIC ART Theatre, Film, Television WWW.NIDA.EDU.AU ABOUT NIDA The National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) is a public, not-for-profit company and is accorded its national status as an elite training institution by the Australian Government. CONTENTS We continue our historical association with the University of New South Wales and maintain FROM THE CHAIRMAN 4 strong links with national and international arts training organisations, particularly through membership of the Australian Roundtable for Arts Training Excellence (ARTATE) and through FROM THE DIRECTOR / CEO 5 industry partners, which include theatre, dance and opera companies, cultural festivals and UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES 8 film and television producers. NIDA delivers education and training that is characterised by quality, diversity, innovation GRADUATE STUDIES 10 and equity of access. Our focus on practice-based teaching and learning is designed to HIGHER EDUCATION STATISTICS 11 provide the strongest foundations for graduate employment across a broad range of career opportunities and contexts. NIDA OPEN 12 Entry to NIDA’s higher education courses is highly competitive, with around 2,000 NIDA OPEN STATISTICS 13 applicants from across the country competing for an annual offering of approximately 75 places across undergraduate and graduate disciplines. The student body for these PRODUCTIONS AND EVENTS AT courses totalled 166 in 2013. NIDA PARADE THEATRES 14 NIDA is funded by the Australian Government through the Ministry for the Arts, DEVELOPMENT 15 Attorney-General’s Department, and is specifically charged with the delivery of performing arts education and training at an elite level. -

The Travelling Table

The Travelling Table A tale of ‘Prince Charlie’s table’ and its life with the MacDonald, Campbell, Innes and Boswell families in Scotland, Australia and England, 1746-2016 Carolyn Williams Published by Carolyn Williams Woodford, NSW 2778, Australia Email: [email protected] First published 2016, Second Edition 2017 Copyright © Carolyn Williams. All rights reserved. People Prince Charles Edward Stuart or ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ (1720-1788) Allan MacDonald (c1720-1792) and Flora MacDonald (1722-1790) John Campbell (1770-1827), Annabella Campbell (1774-1826) and family George Innes (1802-1839) and Lorn Innes (née Campbell) (1804-1877) Patrick Boswell (1815-1892) and Annabella Boswell (née Innes) (1826-1914) The Boswell sisters: Jane (1860-1939), Georgina (1862-1951), Margaret (1865-1962) Places Scotland Australia Kingsburgh House, Isle of Skye (c1746-1816) Lochend, Appin, Argyllshire (1816-1821) Hobart and Restdown, Tasmania (1821-1822) Windsor and Old Government House, New South Wales (1822-1823) Bungarribee, Prospect/Blacktown, New South Wales (1823-1828) Capertee Valley and Glen Alice, New South Wales (1828-1841) Parramatta, New South Wales (1841-1843) Port Macquarie and Lake Innes House, New South Wales (1843-1862) Newcastle, New South Wales (1862-1865) Garrallan, Cumnock, Ayrshire (1865-1920) Sandgate House I and II, Ayr (sometime after 1914 to ???) Auchinleck House, Auchinleck/Ochiltree, Ayrshire Cover photo: Antiques Roadshow Series 36 Episode 14 (2014), Exeter Cathedral 1. Image courtesy of John Moore Contents Introduction .……………………………………………………………………………….. 1 At Kingsburgh ……………………………………………………………………………… 4 Appin …………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Emigration …………………………………………………………………………………… 9 The first long journey …………………………………………………………………… 10 A drawing room drama on the high seas ……………………………………… 16 Hobart Town ……………………………………………………………………………….. 19 A sojourn at Windsor …………………………………………………………………… 26 At Bungarribee ……………………………………………………………………………. -

1 Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2014

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2014 1 Kate Box, Melita Jurisic, Robert Menzies, Hugo Weaving, Ivan Donato, Eden Falk, Paula Arundell and John Gaden in Macbeth. Photo: Brett Boardman Aims of the Company To provide first class theatrical entertainment for the people of Sydney – theatre that is grand, vulgar, intelligent, challenging and fun. That entertainment should reflect the society in which we live thus providing a point of focus, a frame of reference, by which we come to understand our place in the world as individuals, as a community and as a nation. Richard Wherrett, 1980 Founding Artistic Director 5 2014 in Numbers ACTORS AND CREATIVES 237 EMPLOYED $350,791 C R 12TEACHING TIX OF TI KET P ICE TIX SAVINGS PASSED ON TO ARTISTS 733 4,877 SUNCORP TWENTIES CUSTOMERS EMPLOYED REGIONAL $20.834M AND INTERSTATE TOTAL TICKET PERFORMANCES INCOME EARNED WORLD 6PREMIERES 1,187 WEEKS PLAYWRIGHTS AVERAGE OF WORK 9 ON COMMISSION CAPACITY FOR ACTORS 6 7 David Gonski Andrew Chairman Upton In the last four annual reports, I have reported on work undertaken by the organisation to modernise operations and governance structures to best support the Company’s artistic aspirations into the Artistic Director future. Most recently, in 2013, I wrote about the security of 45 year leases over the Roslyn Packer Theatre (formerly Sydney Theatre) and James Duncan in The Long Way Home. Richard Roxburgh in Cyrano de Bergerac. our tenancy at The Wharf, and the subsequent winding up of New Photo: Lisa Tomasetti 2014 was a year that brought the Company together through thick Photo: Brett Boardman South Wales Cultural Management, the body that had previously and thin.