632 WAR and NEUTRALITY Case No. 215 Belligerent Occupation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet 27-50-366 November 2003 Articles Military Commissions: Trying American Justice Kevin J. Barry, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Coast Guard Why Military Commissions Are the Proper Forum and Why Terrorists Will Have “Full and Fair” Trials: A Rebuttal to Military Commissions: Trying American Justice Colonel Frederic L. Borch, III Editorial Comment: A Response to Why Military Commissions Are the Proper Forum and Why Terrorists Will Have “Full and Fair” Trials Kevin J. Barry, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Coast Guard Afghanistan, Quirin, and Uchiyama: Does the Sauce Suit the Gander Evan J. Wallach Note from the Field Legal Cultures Clash in Iraq Lieutenant Colonel Craig T. Trebilcock The Art of Trial Advocacy Preparing the Mind, Body, and Voice Lieutenant Colonel David H. Robertson, The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center & School, U.S. Army CLE News Current Materials of Interest Editor’s Note An article in our April/May 2003 Criminal Law Symposium issue, Moving Toward the Apex: New Developments in Military Jurisdiction, discussed the recent ACCA and CAAF opinions in United States v. Sergeant Keith Brevard. These opinions deferred to findings the trial court made by a preponderance of the evidence to resolve a motion to dismiss, specifically that the accused obtained and presented forged documents to procure a fraudulent discharge. Since the publication of these opinions, the court-matial reached the ultimate issue of the guilt of the accused on remand. The court-martial acquitted the accused of fraudulent separation and dismissed the other charges for lack of jurisdiction. -

HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare

Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare Bern, 15 May 2009 Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research at Harvard University © 2009 The President and Fellows of Harvard College ISBN: 978-0-9826701-0-1 No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed in any form without the prior consent of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Con- fl ict Research at Harvard University. This restriction shall not apply for non-commercial use. A product of extensive consultations, this document was adopted by consensus of an international group of experts on 15 May 2009 in Bern, Switzerland. This document does not necessarily refl ect the views of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research or of Harvard University. Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research Harvard University 1033 Massachusett s Avenue, 4th Floor Cambridge, MA 02138 United States of America Tel.: 617-384-7407 Fax: 617-384-5901 E-mail: [email protected] www.hpcrresearch.org | ii Foreword It is my pleasure and honor to present the HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare. This Manual provides the most up-to-date restatement of exist- ing international law applicable to air and missile warfare, as elaborated by an international Group of Experts. As an authoritative restatement, the HPCR Manual contributes to the practical understanding of this important international legal framework. The HPCR Manual is the result of a six-year long endeavor led by the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research at Harvard University (HPCR), during which it convened an international Group of Experts to refl ect on existing rules of international law applicable to air and missile warfare. -

Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 46 | Issue 3 Article 4 5-2017 A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J. Sfekas Circuit Court for Baltimore City, Maryland Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Sfekas, Stephen J. (2017) "A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 46 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol46/iss3/4 This Peer Reviewed Articles is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COURT PURE AND UNSULLIED: JUSTICE IN THE JUSTICE TRIAL AT NUREMBERG* Hon. Stephen J. Sfekas** Therefore, O Citizens, I bid ye bow In awe to this command, Let no man live Uncurbed by law nor curbed by tyranny . Thus I ordain it now, a [] court Pure and unsullied . .1 I. INTRODUCTION In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the common understanding was that the Nazi regime had been maintained by a combination of instruments of terror, such as the Gestapo, the SS, and concentration camps, combined with a sophisticated propaganda campaign.2 Modern historiography, however, has revealed the -

INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Answers to Your Questions 2

INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Answers to your Questions 2 THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS (ICRC) Founded by five Swiss citizens in 1863 (Henry Dunant, Basis for ICRC action Guillaume-Henri Dufour, Gustave Moynier, Louis Appia and Théodore Maunoir), the ICRC is the founding member of the During international armed conflicts, the ICRC bases its work on International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Additional Protocol I of 1977 (see Q4). Those treaties lay down the ICRC’s right to • It is an impartial, neutral and independent humanitarian institution. carry out certain activities such as bringing relief to wounded, • It was born of war over 130 years ago. sick or shipwrecked military personnel, visiting prisoners of war, • It is an organization like no other. aiding civilians and, in general terms, ensuring that those • Its mandate was handed down by the international community. protected by humanitarian law are treated accordingly. • It acts as a neutral intermediary between belligerents. • As the promoter and guardian of international humanitarian law, During non-international armed conflicts, the ICRC bases its work it strives to protect and assist the victims of armed conflicts, on Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions and internal disturbances and other situations of internal violence. Additional Protocol II (see Index). Article 3 also recognizes the ICRC’s right to offer its services to the warring parties with a view The ICRC is active in about 80 countries and has some 11,000 to engaging in relief action and visiting people detained in staff members (2003). -

High Command Case: a Study in Staff and Command Responsibility

JOHN JAY DOUGLASS* Colonel, JAGC High Command Case: A Study in Staff and Command Responsibility Less than twenty-five years after the conclusion of the major World War I1war crimes trials, international jurists, historians and the general public are not clear as to, nor are they apparently concerned with, the authority, procedure or even the significant legal decisions of the war crimes trials held both in Europe and the Far East following World War 11.1 Even a mere twenty-five years of experience indicates there will be other trials of those accused of criminal acts in war. Such trials, as well as international lawmakers, should well review the German High Command Trial before the United States Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in October 1948. The lessons of this trial may well be the most important of those from any of the trials held following World War 11. The thrust of this trial and its results relate to the authority of command- ers of military forces for actions of their troops and their personal respon- sibility, as well as the responsibility of staff officers in senior staff positions, for'actions taken by them or carried on under their direction. As a result of recent developments within the United States, arising from the war in Vietnam, it is worthwhile to review the German High Command Trial and to analyze its relationship to the present state of the law. The legal question of criminal responsibility of military commanders and staff officers who do *Commandant (Dean), The Judge Advocate General's School, U.S. -

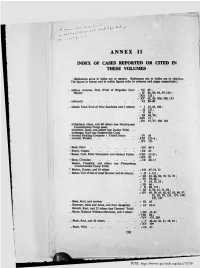

Annex Ii Index of Cases Reported Or Cited in These Volumes

J» ■ i, J L-, UJ> O'- ' / C , " i ANNEX II INDEX OF CASES REPORTED OR CITED IN THESE VOLUMES (References given in italics arc to reports. References not in italics are to citations. The figures in roman and in arabic figures refer to volumes and pages respectively.) Abbaye Ardcnnc Trial (Trial of Brigadier Kurt~ 111 6 9 ; Meyer). ✓ IV 85, 89, 997-110 5 , ; *X1I 123: ✓ X V 62, ¿4, 106,109, 133 - Ahlbrecht ......................................................... X I 89-90 « Almelo Trial (Trial or Otto Sandrock and 3 others)✓ / 35-45,1 0 6 ; ✓ 11 127; w V 1 0 ; . XI 46,50; . X IV 15 ; * X V 47, 97, 108, 184 Allfuldisch, Hans, and 60 others (sec Mauthausen Concentration Camp case). Altstötter, Josef, and others (sec Justkc Trial) .. Ambcrgcr, Karl (sec Dreierwalde Case) - Armour Packing Company v. United States .. s W 54 - Awochi, Washio ..............................................^Xlll 122-4 ; X V 121 » Back, P e t e r ........................................................ ✓/// 60-1 x Bauer, August ..............................................«'IX 65 v Bauer, Carl, Ernst Schramcck and Herbert Falten*Vlll 15-21; v X V 82 v'Baus, Christian ..............................................s l X 68-71 Becker, Friedrich, and others (sec Flossenberg Concentration Camp Trial) t'Becker, Gustav, and 19 others ........................ JVU 67-73,15 ✓ Belsen Trial (Trial of Josef Kramer and 44 others)..11 1-152;✓ ✓ III 6 3 ,6 6 ,6 9 .7 0 ,7 2 ,7 4 ; ✓ IV 79,86 ; ✓ V 14, 15, 23 ; ✓ IX 66 ; ✓ X 68, 173 ; ✓ XI 9,10,11,71,83; ✓ X V 45, 59, 61, 65, 67, 83, 86, 87, 92, 93, 97, 121. -

The Role and Importance of the Hague Conferences: a Historical Perspective

The Role and Importance of the Hague Conferences: A Historical Perspective UNIDIR RESOURCES Acknowledgements Support from UNIDIR’s core funders provides the foundation for all of the Institute’s activities. In addition, this project received support from the Government of the Russian Federation. UNIDIR would like to thank the author of the paper, Nobuo Hayashi. About the author Nobuo Hayashi is a Senior Legal Advisor at the International Law and Policy Institute, based in Oslo, Norway (2012–present). He specializes in international humanitarian law, international criminal law, and public international law. He has over fifteen years’ experience in these areas, performing advanced research, publishing and editing scholarly works, authoring court submissions, advising international prosecutors, and speaking at academic and diplomatic conferences. His most significant works cover military necessity, threat of force, and the law and ethics of nuclear weapons. He also regularly teaches at defence academies, Red Cross conferences and professional workshops, as well as university faculties of law, political science, and peace and security studies. He trains commissioned officers, military lawyers, judges, prosecutors, defence counsel, diplomats and other government officials, humanitarian relief specialists, and NGO representatives from all over the world. Major positions held: Researcher, PluriCourts, University of Oslo Law Faculty (2014–2016); Visiting Lecturer, UN Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (2007–2016); Visiting Professor, International University of Japan (2005–2015); Researcher, Peace Research Institute Oslo (2008–2012); Legal Advisor, Norwegian Centre for Human Rights (2006–2008); Legal Officer, Prosecutions Division, Office of the Prosecutor (OTP), International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (2004–2006); and Associate Legal Officer, ICTY OTP Legal Advisory Section (2000–2003). -

Some International Law Problems Related to Prosecutions Before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

SOME INTERNATIONAL LAW PROBLEMS RELATED TO PROSECUTIONS BEFORE THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA W.J. FENRICK* I. INTRODUCTION The presentation of prosecution cases before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (the Tribunal) will require argument on a wide range of international law issues. It will not be possible, and it would not be desirable, simply to dust off the Nuremberg and Tokyo Judgments, the United Nations War Crimes Commission series of Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals, and the U.S. government's Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No.10 and presume that one has a readily available source of answers for all legal problems. An invaluable foundation for legal argument before the Tribunal is provided by Pictet's Commentaries on the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the International Committee of the Red Cross' (ICRC) Commentaries on the Additional Protocols of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the few cases decided since 1950, old case law, and various learned articles and treatises. They must be reviewed and analyzed. At the same time, however, just as the prosecutors in the post-1945 war crimes trials argued successfully that customary law had evolved after 1907 and 1929, so it is reasonable to presume that customary law has evolved since the Geneva Convention of 1949 and the Additional Protocols of 1977. It is essential to pay due heed to the principles of nullum crimen sine lege and nulla poena sine lege.1 One must, however, distinguish * Senior Legal Advisor, Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. -

The Legal Situation of “Unlawful/Unprivileged Combatants”

RICR Mars IRRC March 2003 Vol. 85 No 849 45 The legal situation of “unlawful/unprivileged combatants” KNUT DÖRMANN* While the discussion on the legal situation of unlawful combatants is not new, it has nevertheless become the subject of intensive debate in recent publications, statements and reports following the US-led military campaign in Afghanistan. Without dealing with the specifics of that armed conflict, this article is intended to shed some light on the legal protections of “unlaw- ful/unprivileged combatants” under international humanitarian law.1 In view of the increasingly frequent assertion that such persons do not have any pro- tection whatsoever under international humanitarian law, it will consider in particular whether they are a category of persons outside the scope of either the Third Geneva Convention (GC III)2 or the Fourth Geneva Convention (GC IV) of 1949.3 On the basis of this assessment the applicable protections will be analysed. Before answering these questions, a few remarks on the ter- minology would seem appropriate. Terminology In international armed conflicts, the term “combatants” denotes the right to participate directly in hostilities.4 As the Inter-American Commission has stated, “the combatant’s privilege (...) is in essence a licence to kill or wound enemy combatants and destroy other enemy military objectives.”5 Consequently (lawful) combatants cannot be prosecuted for lawful acts of war in the course of military operations even if their behaviour would consti- tute a serious crime in peacetime. They can be prosecuted only for violations of international humanitarian law, in particular for war crimes. Once cap- tured, combatants are entitled to prisoner-of-war status and to benefit from the protection of the Third Geneva Convention. -

Detailed Table of Contents (PDF Download)

Contents Preface xxiii Abbreviations and Acronyms xxvii Acknowledgments xxxiii Foreword xxxvii part I Why 1 chapter 1 Foundations 3 A. Purposes 5 1. Protection of Civilians and Others Hors de Combat 7 Constitutional Review of Additional Protocol II 8 2. Minimize Unnecessary Suff ering 9 3. Mission Fulfi llment 10 B. Key Sources of LOAC 11 1. Treaties 11 2. Customary International Law 13 David J. Bederman, International Law Frameworks 13 C. Jus ad Bellum vs. Jus in Bello 16 1. Jus ad Bellum 16 2. Jus ad Bellum in an Age of Counterterrorism 21 3. Separation of Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello 23 Prosecutor v. Fofana and Kondewa 25 Questions for Discussion 27 xi xii Contents D. Intersection with and Distinction from Human Rights Law 30 Th eodor Meron, Th e Humanization of Humanitarian Law 30 Legality of the Th reat or Use of Nuclear Weapons 32 Fourth Periodic Report of the United States of America to the United Nations Committee on Human Rights Concerning the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 34 Questions for Discussion 37 chapter 2 Basic Principles 39 Jean Pictet, Development and Principles of International Humanitarian Law 39 A. Military Necessity 40 Th e United States of America v. Wilhelm List et al. (Th e Hostages Trial) 42 Questions for Discussion 44 B. Humanity 45 Questions for Discussion 47 C. Distinction 48 Legality of the Th reat or Use of Nuclear Weapons 50 Constitutional Review of Additional Protocol II 52 Questions for Discussion 53 D. Proportionality 56 Questions for Discussion 59 chapter 3 Historical Development of LOAC 61 A. -

The Applicability and Application of International Humanitarian Law To

International Review of the Red Cross (2013), 95 (891/892), 561–612. Multinational operations and the law doi:10.1017/S181638311400023X The applicability and application of international humanitarian law to multinational forces Dr Tristan Ferraro* Dr Tristan Ferraro is Legal Adviser in the Legal Division of the International Committee of the Red Cross, based in Geneva. Abstract The multifaceted nature of peace operations today and the increasingly violent environments in which their personnel operate increase the likelihood of their being called upon to use force. It thus becomes all the more important to understand when and how international humanitarian law (IHL) applies to their action. This article attempts to clarify the conditions for IHL applicability to multinational forces, the extent to which this body of law applies to peace operations, the determination of the parties to a conflict involving a multinational peace operation and the classification of such conflict. Finally, it tackles the important question of the personal, temporal and geographical scope of IHL in peace operations. Keywords: multinational operations, multinational forces, international humanitarian law, IHL, applicability of IHL. Over the years, the responsibilities and tasks assigned to multinational forces have transcended their traditional duties of monitoring ceasefires and observation of fragile peace settlements. Indeed, the spectrum of operations in which multinational * This article was written in a personal capacity and does not necessarily reflect the views of the ICRC. © icrc 2014 561 T. Ferraro forces participate (hereinafter ‘peace operations’ or ‘multinational operations’)1, be they conducted under United Nations (UN) auspices or under UN command and control, has steadily widened to embrace such diverse aspects as conflict prevention, peacekeeping, peacemaking, peace enforcement and peacebuilding. -

The Case of Military Occupation', the Journal of Modern History, Vol

University of Birmingham International law and the transformation of war, 1899-1949 Gumz, Jonathan DOI: 10.1086/698960 License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Gumz, J 2018, 'International law and the transformation of war, 1899-1949: the case of military occupation', The Journal of Modern History, vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 621-660. https://doi.org/10.1086/698960 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: © 2018 by The University of Chicago General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive.