The Impact of the Community Based Public Works Programme of the Department of Public Works in Groutville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kim Spingorum

Kindly be advised should you be coming with a boat, jet skis or canoe/kayak to contact our local ski boat club manager, contact person Charles Rautenbach, to get the necessary clearances or any additional info re water sport facilities on the lagoon. Cell: 083 375 5399 Brian is the local skipper for all things fishing and for booking a cruise on the barge on the lagoon – for more details contact, 084 446 6813 / 074 479 0987. Have fun! (Ocean echo fishing charters) Or simply just paddle, fish or swim in our lagoon. – Double or single canoes for hire at R40/per hour from the Lagoon lodge – contact: 032 – 485 3344 For additional water escapades in Durban and surrounds including Ballito please have a look at https://adventureescapades.co.za/water-adventures-in-south-africa/ Sugar Rush fun park for the whole family – www.sugarrush.co.za - on the coastal farmland of the North Coast, on the outskirts of Ballito – please have a look at the website for more information. • Putt-putt with paddling pools after the kids have played their holes • Small winery • The Jump Park • Tuwa Beauty Spa • Petting Zoo – Feathers and Furballs • Sugar rats – Kids Mountain biking, safe and fun! • Reptile Park • Restaurant Holla Trails operates from Sugar rush For those who are interested in doing a bike or for the runners!!– Holla trails can be contacted on +27 074 897 8559 (trail master) or 082 899 3114 (desk phone) – Easy to get to situated on the outskirts of Ballito! A fun way to experience the farm life on the North Coast, the trails are for different levels from under 12 to 70 years. -

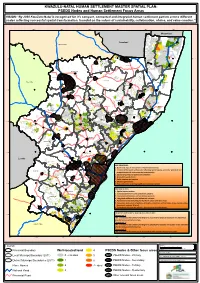

PSEDS Nodes and Human Settlement Focus Areas

KWAZULU-NATAL HUMAN SETTLEMENT MASTER SPATIAL PLAN: PSEDS Nodes and Human Settlement Focus Areas VISION: 29°20'0"E 30°0'0"E 30°40'0"E 31°20'0"E 32°0'0"E 32°40'0"E Mozambique S#Ndumo Emangusi Swaziland S# Mpumalanga S#Phelandaba Umhlambuyalingana LM S#Golela 27°20'0"S 27°20'0"S Pongola S# Jozini LM Charlestown S# Paul-Pietersburg S# S#Jozini eDumbe LM Mbazwana uPhongolo LM S# S#Sodwana Bay S#Louwsburg Mkuze Emadlangeni LM S# S#Utrecht Newcastle LM New Castle S# S#Madadeni S#Vryheid Abaqulusi LM Free State The Big Five False Bay LM S#KwaMduku Nongoma LM S#Nongoma S#Gluckstadt Dannhauser LMDunnhauser S#Hluhluwe 28°0'0"S S# 28°0'0"S S#Hlabisa Dundee Glencoe S# S# Hlabisa LM Endumeni LM S#Nqutu Ulundi LM S#Ulundi Wasbank Mtubatuba LM S# Nquthui LM S#Babanango S#St Lucia S#Mtubatuba Emnambith/Ladysmith LM S#Ekuvukeni Ladysmith Pomeroy S# Indaka LM S# Ntambanana LM Melmoth S# Mfolozi LM S#Nkandla Mthonjaneni LM S#Ntambanana S#Kwambonambi Ezakheni S# Msingai LM Nkandla LM 28°40'0"S 28°40'0"S Bergville S# S#Colenso S#Tugela Ferry S#Empangeni Richards Bay Okhahlamba LM S# uMhlathuze LM S#Winterton S#Weenen uMtshezi LM S#Eshowe uMlalazi LM Mtunzini Kranskop S# S#Loskop S# S#Muden S#Estcourt S#Ginginlovu uMvoti LM S#Greytown S#Isithebe Imbabazane LM Mandeni LM Maphumulo LM Mapumulo S# Mandeni Text S# S#Rockmount Mooi Mphofana LM S#Mooirivier S#Seven Oaks S#Zinkwazi Beach S#Stanger Nottingham Road New Hanover 29°20'0"S S# S# KwaDukuza LM 29°20'0"S uMshwathi LM Wartburg S# Ndwedwe LM uMngeni LM S#Howick Ndwedwe Lesotho S# S#Umhlali S#Hilton Impendle LM S#Tongaat S#Pietermaritzburg S#Impendle Msunduzi LM MSP PRINCIPLES: 1. -

616 Zimbali Suite

ON-LINE “ZOOM” & LIVE AUCTION RESIDENTIAL PROPERTY 95 SOUTHWARD HO’ ROAD PRINCE'S GRANT GOLF ESTATE NORTH COAST, KZN THURSDAY, 17 JUNE 2021 @ 11:00 AM VENUE: THE OYSTER BOX - 2 LIGHTHOUSE ROAD, UMHLANGA ROCKS, KWAZULU-NATAL ANDREW GIDDY: 082 601 9278 | 031 579 4403 WWW.IANWYLES.CO.ZA Viewing by Appointment only Terms & Conditions Please note that in order to be approved for bidding, you are required to send us: Proof of Payment & Original Proof of FICA Documents. R 50 000.00 Registration Deposit by EFT must be paid. All bids are exclusive of Commission + VAT. Ian Wyles Auctioneers may bid up to reserve on behalf of the sellers. The above is subject to change without prior notification. Auctioneer: Ian Wyles 1 CONTENTS PRINCE'S GRANT GOLF ESTATE Property Summary Locality Maps Pictures Additional Information Auction Information Deposit 5% of bid price payable by The Purchaser on the fall of the hammer Commission 10% plus VAT thereon of the bid price payable by the Purchaser on the fall of the hammer Terms and Conditions If you are the successful bidder, the following is applicable: • 45 Day Guarantee Period from confirmation of sale by the Seller • Possession & occupation of property on registration • Electrical (including electric fencing), woodborer and gas compliance for the Purchaser’s account, if applicable Banking Details Ian Wyles Auctioneers and Appraisers (PTY) LTD - (EAAB Approved Trust Account) Account Number – 40-9642-2381 Branch Name – Absa Bank Durban North Swift Code – ABSA ZA JJ Branch Code – 632005 Reference: Use Name and -

•Ar •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ap

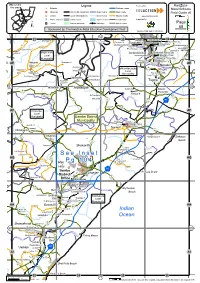

Map covers Legend Produced by: KwaZulu- this area Schools National roads Natal Schools ! Hospitals District Municipalities Major rivers Main roads Field Guide v5 Clinics Local Municipalities Minor rivers District roads www.eduAction.co.za !W Police stations Urban areas Dams / Lakes Local roads Supported by: Towns Nature reserves Railways Minor roads Page 68 Sponsored by: The KwaZulu-Natal Education Development Trust KwaZulu-Natal Dept of Education 58 33 34 35 Udumo H Khayalemfundo Jp 36 Mvumase P Manqindi Jp Siyavikelwa Sp Dendethu P Mandeni P $ Imbewenhle P Ubuhlebesundumbili Jp Ndondakusuka Ss O Thukela S !W Sundumbili P O Iwetane P Khululekani P Siyacothoza P Ethel Mthiyane Lsen Cranburn P Timoni P Maphumulo !!"% !!" Impoqabulungu S Local % Municipality !W 1 North Coast Mandini Pp '!" Nsungwini C Christian Acad Mandini AE AE % O Acad Nyakana P eNdondakusuka 1 Maqumbi P Banguni S 1 #!$ Local Mzobanzi Js Tugela S % O Municipality Lower Tugela P Qondukwazi P Tshelabantu P Ramlakan P &! Shekembula H Mgqwaba- % gqwaba P 1 !W 67 69 Newark P 1 " Hulett P St Christopher P 1 Imbuyiselo S N2 1 1 1 1 1 Nonoti P 1 AF Ndwedwe AF Local Municipality iLembe District Municipality Hulsug P Darnall S 1 Ashville P Lee P % Darnall P Prospect # " Farm P O 1 ()* Bongimfundo P 1 % 1 1 Kearsney P Harry Bodasing P Lethithemba S Ensikeni P See Inset AG O AG New Lubisana P O 1 Pg 104 Guelderland Int Farm ! L Bodasing P O -

Ilembe District Municipality – Quarterly Economic Indicators and Intelligence Report: 4Th Quarter 2011

iLembe District Municipality – Quarterly Economic Indicators and Intelligence Report: 4th Quarter 2011 ILEMBE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY NOVEMBER 2010 QUARTERLY ECONOMIC INDICATORSNOVEMBER 2010 AND INTELLIGENCE REPORT FOURTH QUARTER October - December 2011 Enterprise iLembe Cnr Link Road and Ballito Drive Ballito, KwaZulu-Natal Tel: 032 – 946 1256 Fax: 032 – 946 3515 iLembe District Municipality – Quarterly Economic Indicators and Intelligence Report: 4th Quarter 2011 FOREWORD This intelligence report comprises of an assessment of key economic indicators for the iLembe District Municipality for the fourth quarter of 2011, i.e. October to December 2011. This is the fourth edition of the quarterly reports which are unique to iLembe as we are the only district municipality to publish such a report. The overall objective of this project is to present economic indicators and economic intelligence to assist Enterprise iLembe in driving its mandate, which is to promote trade and investment and to drive economic development in the District of iLembe. This quarter’s edition not only describes historical trends but also takes a brief look at the future of iLembe through the eyes of district planners. Their plan looks forward 30 years to an iLembe that is thriving of the back of large scale agricultural, manufacturing, resort, and renewable energy investments. The result is a highly connected and integrated district, where Ballito and KwaDukuza have formed a metro, and the north coast has become the tourism destination of choice. Readers are asked to comment on this future scenario and the steps needed to get there. This quarter’s report provides also an update on the work we, at Enterprise iLembe, are doing. -

Kwazulu-Natal Proposed Main Seat / Sub District Within the Proposed Magisterial District Kwadukuza Main Seat of Ilembe Magisteri

!C !C^ ñ!.!C !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^!C ^ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^$ !C !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ !C ñ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^!C ^ !C !C !C ñ ^ !C !C ^ $ ^$!C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !.^ ñ $ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C $ !C !C !C ñ $ !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ñ!C!. ^ ^ ^ !C $!. !C^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C ^ !.!C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ñ !C !C !C ñ !.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !Cñ ^$ ^ !C ñ !C ñ!C!.^ !C !. !C !C ^ ^ ñ !. !C !C $^ ^ñ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !. ñ!C !C !C ^ !C ñ!.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C ^!. !. !. !C ^ !C !C !. !C ^ !C !C ^ !C ñ!C !C !. !C $^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !. -

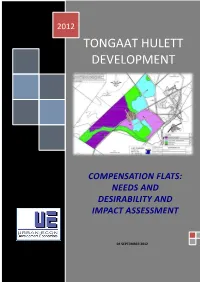

Tongaat Hulett Development

COMPENSATION FLATS: NEEDS AND DESIRABILITY AND IMPACT ASSESSMENT 2012 TONGAAT HULETT DEVELOPMENT COMPENSATION FLATS: NEEDS AND DESIRABILITY AND IMPACT ASSESSMENT 04 SEPTEMBER 2012 URBAN-ECON: Development Economists Page | 1 P O BOX 50834, MUSGRAVE 4062 TEL: 031-2029673 FAX: 031-2029675 E-MAIL: [email protected] COMPENSATION FLATS: NEEDS AND DESIRABILITY AND IMPACT ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Section 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Purpose of the Study ............................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Report Approach and Methodology ....................................................................................... 4 1.4 Report Outline......................................................................................................................... 5 2 Section 2: Spatial Analysis ..................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Proposed Concept plan and Motivation ................................................................................. 6 2.2 Location of the Site ................................................................................................................. 7 2.3 Market Delineation ................................................................................................................ -

Biophysical Surveys of Zinkwazi & Nonoti Estuarie

ORI Unpublished Report No. 310 Biophysical Assessments of the Zinkwazi & Nonoti Estuaries: High & Low Flow Surveys December 2013 Zinkwazi Beach Ratepayers and Residents Compiled For: Association Lower Tugela Biodiversity Protection Project Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund Funded By: & through Wildlands Conservation Trust Compiled By: Fiona MacKay Oceanographic Jill Sheppard Research Bronwyn Goble Institute In Collaboration Council for With: Scientific & Steven Weerts Industrial Research ORI Unpublished Report 310 The ORI Unpublished Report Series is intended to document various activities of the Oceanographic Research Institute. This is the research department of the South African Association for Marine Biological Research. Oceanographic Research Institute P.O. Box 10712 Marine Parade, 4056 Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Tel: +27 31 3288222 Fax: +27 31 3288188 Web site: www.ori.org.za © 2013 Oceanographic Research Institute Title: Biophysical Assessments of the Zinkwazi & Nonoti Estuaries: High & Low Flow Surveys Document Creator/s: Fiona MacKay, Jill Sheppard, Steven Weerts & Bronwyn Goble Client/Funding Zinkwazi Beach Ratepayers and Residents Association Agencies: Lower Tugela Biodiversity Protection Project Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund & through Wildlands Conservation Trust Subject and Zinkwazi & Nonoti Estuaries, baseline biophysical surveys, keywords: macrobenthos, ichthyofauna, information for estuarine management plans and environmental flow assessments Description: This study presents data and information gathered during low (winter, July 2012) and high flow (summer, February 2013) surveys conducted in the Zinkwazi and Nonoti Estuaries. An account of the biophysical condition of each system is presented, including additional material on spatial analysis of land use, coastal vulnerability and interpolation of the estuarine physico- chemical habitat as they pertain to input information towards estuarine management plans and estuarine flow assessment studies. -

Kwazulu-Natal

Chapter 6 KWA-ZULU NATAL PROVINCE 92.1% Provincial Best Performer eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality is the best performing municipality in Kwa-Zulu Natal Province with support from Umgeni Water as their Service Provider. The Municipal Blue Drop Score of 98.77% was achieved. Congratulations! KWA-ZULU NATAL Page 151 Blue Drop Provincial Performance Log – Kwa-Zulu Natal Provincial Blue Drop Blue Drop Log Position Score Blue Drop Blue Drop Water Services Authority 2012 Score 2011 Score 2010 eThekwini Metro (+ Umgeni Water) 1 98.77 95.71 96.10 Newcastle LM (+ Uthukela Water) 2 96.50 75.61 74.80 iLembe DM (+ Umgeni Water) 3 95.38 85.54 50.80 Msundusi LM (+ Umgeni Water) 4 95.38 95.60 73.20 uMzinyathi DM (+ Umgeni Water) 5 93.45 70.01 66.00 City of uMhlathuze LM (+WSSA) 6 92.94 89.26 80.40 Ugu DM (+ Umgeni Water) 7 92.55 92.82 87.40 Umgungundlovu DM 8 92.42 56.22 64.70 Amajuba DM 9 83.31 84.43 56.40 Zululand DM 10 83.05 72.13 59.80 uMkhanyakude DM 11 77.77 32.45 22.40 uThungulu DM 12 72.51 71.31 37.20 Sisonke DM 13 69.35 40.09 53.60 uThukela DM 14 57.39 55.29 54.40 Top 3 The Department wishes to acknowledge and congratulate eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, together with Umgeni Water Board for achieving Provincial Top Performer in the province of Kwa-Zulu Natal. This first place is by a significant margin, which is exceptional, but other municipalities are encouraged to accept the challenge and implement all Blue Drop requirements. -

DC29 Ilembe Draft IDP Review 2014-15

Draft iLembe District Municipality 2014/2015 IDP Review iLembe District Municipality Draft Integrated Development Plan 2014/2015 Review Page | 1 Draft iLembe District Municipality 2014/2015 IDP Review Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................... 5 LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................. 7 LIST OF MAPS ..................................................................................................................................... 8 LIST OF GRAPHS ................................................................................................................................. 9 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT ....................................................................................... 10 FOREWORD BY HIS WORSHIP THE MAYOR ........................................................................................ 12 CHAPTER 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... 13 1.1. WHO ARE WE? ..................................................................................................................... 13 1.2 DEVELOPING THE ILEMBE IDP ............................................................................................... 15 1.3 DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES ............................................................................................... -

GEOGRAPHICAL ASSOCIATION of ZIMBABWE

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs GEOGRAPHICAL ASSOCIATION of ZIMBABWE PROCEEDINGS OF 1984/85 TOWARD A GEOGRAPHY OF CONFLICT J.R Whitlow ZIMBABWE’S APPROACH TO PROTECTED AREA MANAGEMENT G. Child MAFIKENG TO MMABATHO: VILLAGE TO CAPITAL CITY J Cowley SERVICE CENTRES AND SERVICE REGIONS IN THE MAGISTERIAL DISTRICTS OF INANDA AND LOWER TUGELA, NATAL R .A . Heath Distributed free to all members Price $6.00 Back issues of Proceedings are available on request from the Editor CONTENTS Page MEASURES OF INDUSTRIAL DISTRIBUTION IN ZIMBABWE ............ 1 TOWARDS A GEOGRAPHY OF CONFLICT ............................. 11 ZIMBABWE'S APPROACH TO PROTECTED AREA MANAGEMENT ........... 40 MAFIKENG TO MMABATHO: VILLAGE TO CAPITAL CITY ....... ...... 44 SERVICE CENTRES AND SERVICE- REGIONS IN THE MAGISTERIAL DISTRICTS OF INANOA AND LOWER TUGELA, NATAL ....... ........................................ 59 INSTRUCTIONS TO AUTHORS ...... ............................... 70 Notes on Contributors: Dr D.S. Tevera is a Lecturer in Geography at the University of Zimbabwe Mr J. R. Whitlow is a Lecturer in Geography at the University of Zi rababwe Dr G. Child is the Director o-f the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Management Mr J. Cowley is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Education (Geography) at the University of Bophuthatswana, Bophuthatswana. Mrs.R.A. Heath is a Le'cturer in Geography at the University oF 'Zimbabwe. The authors alone are responsible For the opinions expressed in these articles. Articles intended For publication and all correspondence regarding Proceedings should be addressed to the Hon. Editor,' c/o Department oF Geography, University oF Zimbabwe, P.O. -

A0map Province Kwazulunatal

KKwwaaZZuulluu--NNaattaall 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E Petrus Van Der Merwe Haar a n M t z p i Mpa o N i i R42 ru te ma n l laag T n g p LK p L gga h w o s Nyetane Dam K wa o o fu an e K le e p n m e R65 ib s u M M Bos Dam e LK is t o a s e S B Jericho Dam n n uikerbos p rant R35 a de r K kw Sufunga Dam u L M a N i t l y Leeukuil Dam a o e m nd t S o a a b Mk n R38 n o N e K d g e L s G an p Morgenstanddam w tuz r r a GGaauutteenngg t u e hl R51 i M o R547 t it m K u L o i ru l R33 p p r a t LK ts LK i R546 s ie a s R p V i p MMoozzaammbbiiqquuee LK s r R39 X Hendrick Van Eck Dam u t K i L i t R50 K Municipal Demarcation Board u l ei r LK n T Grootvlei Dam - o p V aa w s t l t i pru R e o s l e ok i a e o esb z sutu r l u U t at R549 t B t re i s G G a LK u p l r N Tel: (012) 342 2481 r h p d u s R lo M l i i z t e N R54 o t a T s n K M h R549 L e p a r u l a LK i R35 o t i y M b W LK at s e a o rva u Ndumo l Grootdraaidam n N s d ! g s LKR u w Fax: (012) 342 2480 p z R23 R546 SSwwaazziillaanndd i a r v u LK LK u i m t t l i K a a a a u a R S L K S r L " V a l Heyshope Dam " p s MMppuummaallaannggaa 0 ! 0 R716 W H ' R716 n p Emanguzi ' s le 0 r lo 0 k g ° u ° K i L K s L e a email: [email protected] 7 7 i R82 p t r l 2 2 LK r s K B l u p ip o i Vaaldam t r v t t u R543 d i i i n i u u t LK n r r o e p k w p g R57 s h n s o N K p L s L a M web: www.demarcation.org.za l k Amersfoort Dam N w e a R26 u n vu e m K k a L a S u b B M s t o R716 i o N p z K e a t y r r n i W o s a K u a L N la m m e mbongw