World's Most Profitable Gold Mine – but Not All Glitters In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arend J Hoogervorst1 B.Sc.(Hons), Mphil., Pr.Sci

Audits & Training Eagle Environmental Arend J Hoogervorst1 B.Sc.(Hons), MPhil., Pr.Sci. Nat., MIEnvSci., C.Env., MIWM Environmental Audits Undertaken, Lectures given, and Training Courses Presented2 A) AUDITS UNDERTAKEN (1991 – Present) (Summary statistics at end of section.) Key ECA - Environmental Compliance Audit EMA - Environmental Management Audit EDDA -Environmental Due Diligence Audit EA- External or Supplier Audit or Verification Audit HSEC – Health, Safety, Environment & Community Audit (SHE) – denotes safety and occupational health issues also dealt with * denotes AJH was lead environmental auditor # denotes AJH was contracted specialist local environmental auditor for overseas environmental consultancy, auditing firm or client + denotes work undertaken as an ICMI-accredited Lead Auditor (Cyanide Code) No of days shown indicates number of actual days on site for audit. [number] denotes number of days involved in audit preparation and report write up. 1991 *2 day [4] ECA - AECI Chlor-Alkali Plastics, Umbogintwini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. November 1991. *2 day [4] ECA - AECI Chlor-Alkali Plastics- Environmental Services, Umbogintwini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. November 1991. *2 Day [4] ECA - Soda Ash Botswana, Sua Pan, Botswana. November 1991. 1992 *2 Day [4] EA - Waste-tech Margolis, hazardous landfill site, Gauteng, South Africa. February 1992. *2 Day [4] EA - Thor Chemicals Mercury Reprocessing Plant, Cato Ridge, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. March 1992. 2 Day [4] EMA - AECI Explosives Plant, Modderfontein, Gauteng, South Africa. March 1992. *2 Day [4] EMA - Anikem Water Treatment Chemicals, Umbogintwini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. March 1992. *2 Day [4] EMA - AECI Chlor-Alkali Plastics Operations Services Group, Midland Factory, Sasolburg. March 1992. *2 Day [4] EMA - SA Tioxide factory, Umbogintwini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. -

Ore Genesis and Modelling of the Sadiola Hill Gold Mine, Mali Geology Honours Project

ORE GENESIS AND MODELLING OF THE SADIOLA HILL GOLD MINE, MALI GEOLOGY HONOURS PROJECT Ramabulana Tshifularo Student number: 462480 Supervisor: Prof Kim A.A. Hein Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Kim Hein for giving me the opportunity to be part of her team and, for helping and motivating me during the course of the project. Thanks for your patience, constructive comments and encouragement. Thanks to my family and my friends for the encouragements and support. Table of contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………..i Chapter: 1 1.1 Introduction……………………………………………………..........................................1 1.2 Location and Physiography……………………………………………………………...2 1.3 Aims and Objectives…………………………………………………………………….3 1.4 Abbreviations and acronyms…………………………………………………………….3 Chapter 2 2.1 Regional Geology………………………………………………………………………..4 2.1.1 Geology of the West African Craton…………………………………………………..4 2.1.2 Geology of the Kedougou-Kéniéba Inlier……………………………………………..5 2.2 Mine geology…………………………………………………………………………….6 Lithology………………………………………………………………………………8 Structure……………………………………………………………………………….8 Metamorphism………………………………………………………………………...9 Gold mineralisation and metallogenesis………………………………………………9 2.4 Previously suggested genetic models…………………………………………………..10 Chapter3: Methodology…………………………………………………………………....11 Chapter 4: Host rocks in drill core…......................................................................................13 4.1 Drill core description….........................................................................................................13 -

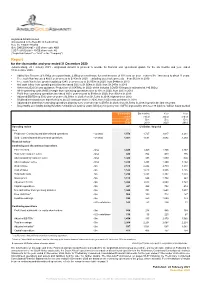

Year End 2020

AngloGold Ashanti Limited (Incorporated in the Republic of South Africa) Reg. No. 1944/017354/06 ISIN: ZAE000043485 – JSE share code: ANG CUSIP: 035128206 – NYSE share code: AU (“AngloGold Ashanti” or “AGA” or the “Company”) Report for the six months and year ended 31 December 2020 Johannesburg, 22 February 2021 - AngloGold Ashanti is pleased to provide its financial and operational update for the six months and year ended 31 December 2020. • Added Ore Reserve of 6.1Moz on a gross basis, 2.6Moz on a net basis, for a net increase of 10% year-on-year - reserve life ∧ increased to about 11 years • Free cash flow increased 485% year-on-year to $743m in 2020 – excluding asset sale proceeds – from $127m in 2019 • Free cash flow before growth capital up 124% year-on-year to $1,003m in 2020, from $448m in 2019 • Net cash inflow from operating activities increased 58% to $1,654m in 2020, from $1,047m in 2019 • Achieved 2020 full year guidance: Production of 3.047Moz in 2020, which includes COVID-19 impacts estimated at 140,000oz • All-in sustaining costs (AISC) margin from continuing operations rose to 40% in 2020, from 28% in 2019 • Profit from continuing operations increased 160% year-on-year to $946m in 2020, from $364m in 2019 • Adjusted EBITDA up 50% year-on-year to $2,593m in 2020, from $1,723m in 2019; highest since 2012 • Dividend increased more than fivefold to 48 US cents per share in 2020, from 9 US cents per share in 2019 • Adjusted net debt from continuing operations down by 62% year-on-year to $597m in 2020, from $1,581m in 2019; -

Anglogold Ashanti Holdings Plc Anglogold Ashanti Limited

Use these links to rapidly review the document TABLE OF CONTENTS Prospectus Supplement TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Table of Contents Filed pursuant to Rule 424(b)(5) Registration Nos. 333-182712 and 333-182712-02 CALCULATION OF REGISTRATION FEE Amount of Registration Title of Each Class of Aggregate Securities to be Registered Offering Price Fee (1) 5.125% Notes due 2022 of AngloGold Ashanti Holdings plc $750,000,000 $85,950 Guarantee of AngloGold Ashanti Limited in connection with the 5.125% Notes due 2022 (2) — — (1) Calculated in accordance with Rule 457(r) under the Securities Act of 1933. (2) Pursuant to Rule 457(n) under the Securities Act of 1933, no separate fee is payable with respect to the guarantee of AngloGold Ashanti Limited in connection with the guaranteed debt securities. Prospectus Supplement to Prospectus dated July 17, 2012 GRAPHIC AngloGold Ashanti Holdings plc $750,000,000 5.125% notes due 2022 Fully and Unconditionally Guaranteed by AngloGold Ashanti Limited The 5.125% notes due 2022, or the "notes", will bear interest at a rate of 5.125% per year. AngloGold Ashanti Holdings plc, or "Holdings", will pay interest on the notes each February 1 and August 1, commencing on February 1, 2013. Unless Holdings redeems the notes earlier, the notes will mature on August 1, 2022. The notes will rank equally with Holdings' senior, unsecured debt obligations and the guarantee will rank equally with all other senior, unsecured debt obligations of AngloGold Ashanti Limited. Holdings may redeem some or all of the notes at any time and from time to time at the redemption price determined in the manner described in this prospectus supplement. -

Golden Rules Making the Case for Responsible Mining

GOLDEN RULES Making the case for responsible mining A REPORT BY EARTHWORKS AND OXFAM AMERICA Contents Introduction: The Golden Rules 2 Grasberg Mine, Indonesia 5 Yanacocha Mine, Peru, and Cortez Mine, Nevada 7 BHP Billiton Iron Ore Mines, Australia 9 Hemlo Camp Mines, Canada 10 Mongbwalu Mine, the Democratic Republic of Congo 13 Rosia Montana Mine, Romania 15 Marcopper Mine, the Philippines, and Minahasa Raya and Batu Hijau Mines, Indonesia 17 Porgera Gold Mine, Papua New Guinea 18 Junín Mine, Ecuador 21 Akyem Mine, Ghana 22 Pebble Mine, Alaska 23 Zortman-Landusky Mine, Montana 25 Bogoso/Prestea Mine, Ghana 26 Jerritt Canyon Mine, Nevada 27 Summitville Mine, Colorado 29 Following the rules: An agenda for action 30 Notes 31 Cover: Sadiola Gold Mine, Mali | Brett Eloff/Oxfam America Copyright © EARTHWORKS, Oxfam America, 2007. Reproduction is permitted for educational or noncommercial purposes, provided credit is given to EARTHWORKS and Oxfam America. Around the world, large-scale metals mining takes an enormous toll on the health of the environment and communities. Gold mining, in particular, is one of the dirtiest industries in the world. Massive open-pit mines, some measuring as much as two miles (3.2 kilometers) across, generate staggering quantities of waste—an average of 76 tons for every ounce of gold.1 In the US, metals mining is the leading contributor of toxic emissions to the environment.2 And in countries such as Ghana, Romania, and the Philippines, mining has also been associated with human rights violations, the displacement of people from their homes, and the disruption of traditional livelihoods. -

Geometry and Genesis of the Giant Obuasi Gold Deposit, Ghana

Geometry and genesis of the giant Obuasi gold deposit, Ghana Denis Fougerouse, BSc, MSc This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Centre for Exploration Targeting School of Earth and Environment The University of Western Australia July 2015 Supervisors: Dr Steven Micklethwaite Dr Stanislav Ulrich Dr John M Miller Professor T Campbell McCuaig ii "It never gets easier, you just go faster" Gregory James LeMond iv Abstract Abstract The supergiant Obuasi gold deposit is the largest deposit hosted in the Paleoproterozoic Birimian terranes of West Africa (62 Moz, cumulative past production and resources). The deposit is hosted in Kumasi Group sedimentary rocks composed of carbonaceous phyllites, slates, psammites, and volcaniclastic rocks intruded by different generations of felsic dykes and granites. In this study, the deformation history of the Obuasi district was re-evaluated and a three stage sequence defined based on observations from the regional to microscopic scale. The D1Ob stage is weakly recorded in the sedimentary rocks as a layer-parallel fabric. The D2Ob event is the main deformation stage and corresponds to a NW-SE shortening, involving tight to isoclinal folding, a pervasive subvertical S2Ob cleavage striking NE, as well as intense sub-horizontal stretching. Finally, a N-S shortening event (D3Ob) formed an ENE-striking, variably dipping S3Ob crenulation cleavage. Three ore bodies characteristic of the three main parallel mineralised trends were studied in details: the Anyankyerem in the Binsere trend; the Sibi deposit in the Gyabunsu trend, and the Obuasi deposit in the main trend. In the Obuasi deposit, two distinct styles of gold mineralisation occur; (1) gold-bearing sulphides, dominantly arsenopyrite, disseminated in metasedimentary rocks and (2) native gold hosted in quartz veins up to 25 m wide. -

Modelling the Optimum Interface Between Open Pit and Underground Mining for Gold Mines

MODELLING THE OPTIMUM INTERFACE BETWEEN OPEN PIT AND UNDERGROUND MINING FOR GOLD MINES Seth Opoku A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Johannesburg 2013 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. Where use was made of the work of others, it was duly acknowledged. It is being submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before in any form for any degree or examination at any other university. Signed …………………………….. (Seth Opoku) This……………….day of……………..………2013 i ABSTRACT The open pit to underground transition problem involves the decision of when, how and at what depth to transition from open pit (OP) to underground (UG). However, the current criteria guiding the process of the OP – UG transition are not well defined and documented as most mines rely on their project feasibility teams’ experiences. In addition, the methodologies used to address this problem have been based on deterministic approaches. The deterministic approaches cannot address the practicalities that mining companies face during decision-making, such as uncertainties in the geological models and optimisation parameters, thus rendering deterministic solutions inadequate. In order to address these shortcomings, this research reviewed the OP – UG transition problem from a stochastic or probabilistic perspective. To address the uncertainties in the geological models, simulated models were generated and used. In this study, transition indicators used for the OP - UG transition were Net Present Value (NPV), ratio of price to cost per ounce of gold, stripping ratio, processed ounces and average grade at the run of mine pad. -

The Yatela Gold Deposit: 2 Billion Years in the Making

Journal of African Earth Sciences 112 (2015) 548e569 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of African Earth Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jafrearsci The Yatela gold deposit: 2 billion years in the making * K.A.A. Hein a, , I.R. Matsheka a, O. Bruguier b, Q. Masurel c, D. Bosch b, R. Caby b, P. Monie b a School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa b Geosciences Montpellier, UMR 5243 e CC 60, Universite Montpellier 2, Place E. Bataillon, 34095 Montpellier Cedex 5, France c Centre for Exploration Targeting, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, Western Australia, Australia article info abstract Article history: Gold mineralisation in the Yatela Main gold mine is hosted in a saprolitic residuum situated above Received 13 February 2015 Birimian supracrustal rocks, and at depth. The supracrustal rocks comprise metamorphosed calcitic and Received in revised form dolomitic marbles that were intruded by diorite (2106 ± 10 Ma, 207Pb/206Pb), and sandstone-siltstone- 1 July 2015 shale sequences (youngest detrital zircon population dated at 2139 ± 6 Ma). In-situ gold-sulphide Accepted 15 July 2015 mineralisation is associated with hydrothermal activity synchronous to emplacement of the diorite and Available online 5 August 2015 forms a sub-economic resource; however, the overlying saprolitic residuum hosts economic gold min- eralisation in friable lateritized palaeosols and aeolian sands (loess). Keywords: West African craton Samples of saprolitic residuum were studied to investigate the morphology and composition of gold Mali grains as a proxy for distance from source (and possible exploration vector) because the deposit hosts Kedougou-K eni eba Inlier both angular and detrital gold suggesting both proximal and distal sources. -

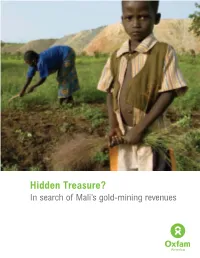

Hidden Treasure? in Search of Mali’S Gold-Mining Revenues a C I R E M a M a F X O / F F O L E T T E R B

Hidden Treasure? In search of Mali’s gold-mining revenues A C I R E M A M A F X O / F F O L E T T E R B Authors Rani Parker (Ph.D., George Washington University) is founder of Business-Community Synergies, a development economist, and a leading authority on corporate-community engagement. Parker has 20 years' experience in international development, including consultancies with organizations such as CARE, the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the UN Development Program (UNDP), and multi- national companies in the energy and extractive industries. Fred Wood (Ph.D., University of London) is an internationally recognized expert on early childhood and youth development. For 12 years, Dr. Wood served as director of education for Save the Children. His consulting projects have included Save the Children, UNICEF, and the World Bank. FRONT COVER: Niama Makalu, 22, and her nephew, Amidou Dembelle, working in a field of groundnuts against the backdrop of a waste dump area for the Sadiola Hill Gold Mine in Mali. Their families were among the many people displaced when mining began in the area in the mid-1990s. Makalu, who is married to the chief of Sadiola, is now—like many others—forced to cultivate food for her family on land in close proximity to mine waste. What’s more, since the Sadiola Hill Mine now occupies much of the area’s former agricultural land, local people have no viable alternatives to farming on these few remaining sites. Above: Sign and fence on the border of the Sadiola Hill Mine, barring trespassers from land that has been conceded to the mining company. -

Randgold Resources Annual Report 2006 01 Chairman’S Statement

Value creation is in our DNA ANNUAL REPORT 2006 Mission Randgold Resources’ focus is on the creation of value through the discovery and development of world class gold projects. IFC Corporate profile and mission 01 2006 highlights Corporate profile 02 Chairman’s statement 04 Directors 06 Management Randgold Resources is an African focused gold mining and 08 Chief executive’s report exploration business incorporated in Jersey in the Channel REVIEW OF OPERATIONS Islands in 1995 and listed on the London Stock Exchange in 11 Financial review 1997 and on Nasdaq in 2002. 13 Operations and projects 13 Loulo mine Its discoveries to date include the 7.5 million ounce Morila deposit 24 Morila mine in southern Mali, the +6 million ounce Yalea deposit at Loulo in 29 Tongon project western Mali and the 3 million ounce Tongon deposit in the Côte Annual resource and reserve declaration 31 d’Ivoire. 32 Table of mineral rights 33 Exploration review The company financed and developed the Morila mine which 42 New business was brought into production in October 2000 and to date has 43 Social responsibility 43 Policy statement produced more than 4 million ounces of gold. It also financed 44 Environmental report and developed the Loulo mine, which was officially opened in 44 Human resources report November 2005. Loulo’s gold production is planned to average DIRECTORS’ REPORTS 250 000 ounces per year until 2009, when Yalea underground 47 Corporate governance will start contributing. The underground development will 53 Remuneration committee report significantly extend the mine’s production and life and is expected 59 Directors’ report to average above 350 000 ounces per year during the seven 60 Statement of directors’ responsibilities and year period from 2009 to 2015. -

Auditor Credentials Form

Auditor Credentials Form Facility Audited: Golden Star Wassa Gold Mine, Ghana. th th Date: - 7 – 11 October 2019 Lead Auditor and Technical Auditor Credentials Lead Auditor: Arend Hoogervorst Eagle Environmental Tel: - +27 31 7670244 Private Bag X06 KLOOF 3640, South Africa Email: - [email protected] Certifying Organization: Name: Exemplar Global Auditor Certification Number: 12529 Telephone Number: - +61 2 4728 4600 Address: P O Box 347, Penrith BC, NSW 2751, Australia Web Site Address: - http://www.exemplarglobal.org/ Minimum experience: 3 audits in past 7 years as Lead Auditor Year Type of Facility, Type of Audit Led Country & State/Province 1991 to 2007 – 111 Chemicals, manufacturing, oil and gas, South Africa, Botswana, audits (Audit logs mining (gold, coal, chrome), foods, and Mozambique, Mali, Namibia, Ghana held by Exemplar heavy industry sectors. EMS, Global & ICMI) Compliance, Environmental Due Diligence, HSEC, SHE audits. Lead Auditor in 81 audits. 2006 ICMI Cyanide Code Compliance Audits: Lead Auditor *Sasol Polymers Cyanide Plants 1 & 2 South Africa and Storage Areas (Production) *Sasol SiLog (Transportation) South Africa 2007 ICMI Cyanide Code Compliance Audits: Lead Auditor *AngloGold Ashanti West Gold Plant South Africa *AngloGold Ashanti East Gold Acid South Africa Float Plant *AngloGold Ashanti Noligwa Gold South Africa Plant *AngloGold Ashanti Kopanang Gold South Africa Plant *AngloGold Ashanti Savuka Gold Plant South Africa *AngloGold Ashanti Mponeng Gold South Africa Plant 2007 ICMI Cyanide Code Gap Analyses: Lead -

Operating Mines

Search Site Operations SADIOLA GOLD MINE, MALI Sadiola Gold Mine, Mali Overview Geology & Mineralization Mining & Processing Outlook Ownership 41% IAMGOLD, 41% AngloGold Ashanti, Government of Mali 18% Operator AngloGold Ashanti Location The Sadiola Gold Mine is located in southwest Mali, West Africa near the Senegal Mali border, approximately 70 kilometres south of the town of Kayes, the regional capital. Kayes has a population of roughly 127,000 people and is located 510 kilometres northwest of the Mali capital Bamako. The Republic of Mali is a landlocked nation bordering Algeria on the north, Niger on the east, Burkina Faso and the Côte d'Ivoire on the south, Guinea on the southwest and Senegal and Mauritania on the west. The country is just over 1,240,000 km² with an estimated population of almost 12,000,000. The Sadiola mining permit covers an area of 302 km² in a remote part of Mali with little infrastructure. The minesite is accessed by a regional gravel road to Kayes. There is an airstrip at the Sadiola Gold Mine capable of handling light chartered aircraft. Kayes is serviced by rail, road and air from Bamako and from Dakar, the capital of Senegal. Bamako has an international airport with daily flights to many West African and European destinations. Dakar is a major port of entry to West Africa by sea and air and the primary supply route for imported goods coming to the minesite. History The Sadiola mine is a joint venture operation with AngloGold Ashanti and accounts for roughly 10% of IAMGOLD’s production. The existing plant was not built for hard rock processing and because the mine is nearing the end of its supply of oxide ore, or soft rock, an expansion is necessary.