Natal and Breeding Dispersal in House Wrens (Troglodytes Aedon)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Troglodytes Troglodytes

Troglodytes troglodytes -- (Linnaeus, 1758) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PASSERIFORMES -- TROGLODYTIDAE Common names: Winter Wren; Wren European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) In Europe this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend appears to be stable, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. Within the EU27 this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). Despite the fact that the population trend appears to be decreasing, the decline is not believed to be sufficiently rapid to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in the EU27. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Albania; Andorra; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Faroe Islands (to DK); Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iceland; Ireland, Rep. -

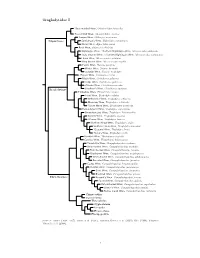

Troglodytidae Species Tree

Troglodytidae I Rock Wren, Salpinctes obsoletus Canyon Wren, Catherpes mexicanus Sumichrast’s Wren, Hylorchilus sumichrasti Nava’s Wren, Hylorchilus navai Salpinctinae Nightingale Wren / Northern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus philomela Scaly-breasted Wren / Southern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus marginatus Flutist Wren, Microcerculus ustulatus Wing-banded Wren, Microcerculus bambla ?Gray-mantled Wren, Odontorchilus branickii Odontorchilinae Tooth-billed Wren, Odontorchilus cinereus Bewick’s Wren, Thryomanes bewickii Carolina Wren, Thryothorus ludovicianus Thrush-like Wren, Campylorhynchus turdinus Stripe-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus nuchalis Band-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus zonatus Gray-barred Wren, Campylorhynchus megalopterus White-headed Wren, Campylorhynchus albobrunneus Fasciated Wren, Campylorhynchus fasciatus Cactus Wren, Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Yucatan Wren, Campylorhynchus yucatanicus Giant Wren, Campylorhynchus chiapensis Bicolored Wren, Campylorhynchus griseus Boucard’s Wren, Campylorhynchus jocosus Spotted Wren, Campylorhynchus gularis Rufous-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus capistratus Sclater’s Wren, Campylorhynchus humilis Rufous-naped Wren, Campylorhynchus rufinucha Pacific Wren, Nannus pacificus Winter Wren, Nannus hiemalis Eurasian Wren, Nannus troglodytes Zapata Wren, Ferminia cerverai Marsh Wren, Cistothorus palustris Sedge Wren, Cistothorus platensis ?Merida Wren, Cistothorus meridae ?Apolinar’s Wren, Cistothorus apolinari Timberline Wren, Thryorchilus browni Tepui Wren, Troglodytes rufulus Troglo dytinae Ochraceous -

Cryptic Speciation in a Holarctic Passerine Revealed by Genetic and Bioacoustic Analyses

Molecular Ecology (2008) 17, 2691–2705 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03769.x CBlackwell Publrishing Lytd ptic speciation in a Holarctic passerine revealed by genetic and bioacoustic analyses DAVID P. L. TOEWS and DARREN E. IRWIN Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, 6270 University Blvd., Vancouver, BC Canada V6T 1Z4 Abstract There has been much controversy regarding the timing of speciation events in birds, and regarding the relative roles of natural and sexual selection in promoting speciation. Here, we investigate these issues using winter wrens (Troglodytes troglodytes), an unusual example of a passerine with a Holarctic distribution. Geographical variation has led to speculation that the western North American form Troglodytes troglodytes pacificus might be a distinct biological species compared to those in eastern North America (e.g. Troglodytes troglodytes hiemalis) and Eurasia. We located the first known area in which both forms can be found, often inhabiting neighbouring territories. Each male wren in this area sings either western or eastern song, and the differences in song are as distinct in the contact zone as they are in allopatry. The two singing types differ distinctly in mitochondrial DNA sequences and amplified fragment length polymorpism profiles. These results indicate that the two forms are reproductively isolated to a high degree where they co-occur and are therefore separate species. DNA variation suggests that the initial split between the two species occurred before the Pleistocene, quite long ago for sister species in the boreal forest. Surprisingly, the two forms are similar in morphometric traits and habitat characteristics of territories. These findings suggest that sexual selection played a larger role than habitat divergence in generating reproductive isolation, and raise the possibility that there are other such morphologically cryptic species pairs in North America. -

Diel Fledging Patterns Among Grassland Passerines: Relative Impacts of Energetics and Predation Risk

Volume 135, 2018, pp. 1100–1112 DOI: 10.1642/AUK-17-213.1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Diel fledging patterns among grassland passerines: Relative impacts of energetics and predation risk Christine A. Ribic,1* Christoph S. Ng,2 Nicola Koper,2 Kevin Ellison,3 Pamela J. Pietz,4 and David J. Rugg5 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Wisconsin Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, USA 2 Natural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada 3 Northern Great Plains Program, World Wildlife Fund, Bozeman, Montana, USA 4 U.S. Geological Survey (emeritus), Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, North Dakota, USA 5 U.S. Forest Service, Research and Development, Madison, Wisconsin, USA * Corresponding author: [email protected] Submitted November 6, 2017; Accepted July 3, 2018; Published September 12, 2018 ABSTRACT The time of day that nestlings fledge from a nest is thought to be shaped by predation risk and energetics. To minimize predation risk, fledging is predicted to start as early in the day as possible so that nestlings can maximize time outside the nest to find a safe place to stay before nightfall. Fledging times are predicted to be tightly grouped and to not be affected by the number of nestlings, given that all nestlings are responding to the same relative risk of predation. Conversely, energetic considerations predict that fledging time of day should vary so that nestlings can maximize energy intake before having to forage for themselves. However, data to evaluate the relative importance of these drivers in grassland birds are scarce because of the difficulty of observing nestlings as they fledge. -

The Northern Colombia Birding Trail

TRAVEL ITINERARY The Northern Colombia Birding Trail Colombia has the richest birdlife on the planet with more than 1,900 species! Enjoy the spectacle while helping communities conserve their local natural heritage. Vermilion Cardinal. Photo: Luis E. Urueña/Manakin Nature Tours audubon.org Colombia is one of the world’s these mountains offer a lot more local people through birdwatching “megadiverse” countries, hosting to Colombia than just exportable you can help make a difference. The close to 10% of the planet’s species, stimulants. Each of the ranges, and project trained local Colombians to with more than 1,900 species of the dense tropical jungles between become bird guides and ecotourism birds—a figure that continues to them, house a variety of habitats for service providers helping give an increase every year. The country has birds and other wildlife. The Northern economic value to birds and the nearly 20 percent of the world’s total Colombia Birding trail is a series forests that sustain them. The bird species, including 200 migratory of ecolodges, national parks, and Northern Colombia Birding Trail species, 155 threatened birds, and 79 otherwise-notable habitats in the helps conserve critical habitat and endemics. Perijá region, in the Sierra Nevada de species—it is also helping improve Colombia sits atop South America, Santa Marta, and along the Caribbean the income of the local communities flanked by Panamá, Ecuador, coast that provide particularly good by generating new jobs. In fact, more Venezuela, Peru, and Brazil; its birding opportunities for extreme than 40 community members and southern reaches straddle the and not-so-extreme birders alike. -

Conspecific Nest Aggression of The

CONSPECIFIC NEST AGGRESSION OF THE PACIFIC WREN ON VANCOUVER ISLAND, BRITISH COLUMBIA ANN NIGHTINGALE and RON MELCER, JR., Rocky Point Bird Observatory, Suite #170, 1581-H Hillside Avenue, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V8T 2C1; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Five of the ten wren species in North America are known to destroy nests of conspecifics. These include the Cactus Wren (Campylorhynchus brunneica- pillus), Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii), Sedge Wren (Cistothorus platensis), Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris), and House Wren (Troglodytes aedon). However, none of the Winter Wren complex, recently split as the Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis), Pacific Wren (T. pacificus), and Eurasian Wren (T. troglodytes), have been documented to do so in experiments or by observation of natural behavior. Here we present a detailed chronology of a nesting of the Pacific Wren—the first report of conspecific nest aggression in the Winter Wren complex. On 15 May 2011, in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a Pacific Wren approached another’s nest under video surveillance and removed two 9-day-old chicks. The nonparental adult returned to the nest, apparently attempting to kill and/or and remove the remaining two chicks, several times over 4.75 hours but was not successful. Although our findings are limited to a single event, they are consistent with those of other wrens. Birds are known to destroy the nests and eggs or remove the young from nests of other species, as well as conspecifics, to reduce competition for nests, food, perches, and, in polygynous species, for the male’s parental care (Fox 1975, Verner 1975, Picman 1977a, Jones 1982). -

Detection of Termites and Other Insects Consumed by African Great Apes Using Molecular Fecal Analysis

OPEN Detection of Termites and Other Insects SUBJECT AREAS: Consumed by African Great Apes using DNA SEQUENCING ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR Molecular Fecal Analysis ENTOMOLOGY Ibrahim Hamad1, Eric Delaporte2, Didier Raoult1 & Fadi Bittar1 Received 1Aix-Marseille Universite´, URMITE, UM63, CNRS 7278, IRD 198, Inserm 1095, 13005 Marseille, France, 2Institut de Recherche 14 October 2013 pour le De´veloppement, University Montpellier 1, UMI 233, Montpellier, France. Accepted 11 March 2014 The consumption of insects by apes has previously been reported based on direct observations and/or trail Published signs in feces. However, DNA-based diet analyses may have the potential to reveal trophic links for these wild species. Herein, we analyzed the insect-diet diversity of 9 feces obtained from three species of African 27 March 2014 great apes, gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and bonobo (Pan paniscus), using two mitochondrial amplifications for arthropods. A total of 1056 clones were sequenced for Cyt-b and COI gene libraries, which contained 50 and 56 operational taxonomic units (OTUs), respectively. BLAST Correspondence and research revealed that the OTUs belonged to 32 families from 5 orders (Diptera, Isoptera, Lepidoptera, requests for materials Coleoptera, and Orthoptera). While ants were not detected by this method, the consumption of flies, beetles, moths, mosquitoes and termites was evident in these samples. Our findings indicate that molecular should be addressed to techniques can be used to analyze insect food items in wild animals. F.B. (fadi.bittar@univ- amu.fr) nvestigating the diets of primate populations elucidates their behavioral ecology and evolution and clarifies dietary differences among the same species in different habitats and among different species in shared I habitats1. -

Troglodytes Musculus (Southern House Wren)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Troglodytes musculus (Southern House Wren) Family: Troglodytidae (Wrens) Order: Passeriformes (Perching Birds) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Southern house wren, Troglodytes musculus. [http://www.ttnaturelink.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/House-Wren-Garden-Birds-Trinidad.jpg, downloaded 8 March 2017] TRAITS. Troglodytes musculus size ranges from 11.5-12.5cm for both male and female, and they weigh about 12g (Handbook of the birds of the world, 2017). The crown and back are grey-brown, with blackish barring on the wing and tail, and a faint eye ring and eyebrow (Fig. 1). The thin long bill has a blackish upper mandible and a black-tipped yellowish or pale grey lower mandible. The legs are grey or pinkish, and there is a cocked short tail (Wiwords, 2017). DISTRIBUTION. The species can be found all over South America, parts of Central America, and some Caribbean islands (Fig. 2), including Trinidad and Tobago. HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. The southern house wren can be found almost everywhere; this includes arid areas or those with high rainfall. Troglodytes musculus spend their time foraging for food or nest building. During the breeding season, the male and female wren share the labour of UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology nest building, both wrens contribute to collecting the first sticks for the preliminary part of the nest construction, afterwards the job of lining is left to the female while the male continues to collect more sticks while singing (Skutch, 1953). -

St Kilda & the Hebrides

St Kilda & the Hebrides - Islands on the Edge of the Atlantic Naturetrek Tour Report 26 May - 1 June 2018 Basking Shark Blackhouses in Village Bay, St. Kilda Stac an Armin, St. Kilda Common Dolphin Report & images compiled by Sara Frost Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report St Kilda & the Hebrides - Islands on the Edge of the Atlantic Tour participants: Sara Frost (leader) with a group of 12 Naturetrek clients Day 1 Saturday 26th May Oban to Mull Our wonderful tour of the Hebrides started in the vibrant seaside town of Oban. Most of the group dropped off their luggage with Sara at noon and then wandered around the town and had lunch at one of the nearby cafes, as the sun shone down on the bustling harbour. We met again at 3pm and boarded the Elizabeth G – our home for the next week! We were greeted with prosecco, scones (with strawberries and cream) and canapés, and set off up the Sound of Mull into glorious sunshine! Within half an hour of travelling up the sound we saw Common Terns, gulls, Grey Herons and both Common and Grey Seals. We continued round the north of Mull, anchoring for the evening at Croig, enjoying a wonderful view of the coast from one side of the vessel and sea on the other as we had the first of many superb evening meals. Around 9pm we went outside to look for Otters and within 15 minutes Sara pointed one out swimming along the shore, 100 metres away – success! Those on deck watched as it made its way along the shore line, surfacing regularly as it hunted for crabs and fish, eventually emerging onto a rock to clean itself before slipping back into the water and out of view. -

Wonderful Wrens

ABOUT BIRDS Wonderful Wrens iny, restless and pugnacious, the Wren of the upland fringe. The species also breeds is one of our most familiar songbirds, on the sea cliffs of offshore islands, where it T widespread across Britain & Ireland occurs in a number of distinct island forms (see and a regular user of the garden environment. page 11), exploiting the tide line for feeding Many books describe the Wren as being opportunities. secretive but, while it is often overlooked, Male Wrens establish their breeding it certainly does not hide itself away from territories in early spring, each proclaiming Man. It would, perhaps, be better described as ownership through a surprisingly powerful being indifferent to us and to our activities. song. Such territory holders are highly The Wren population is at something of aggressive towards other males and use a By Mike Toms a peak at the moment, thanks to a run of combination of song and posture to see off GBW Organiser mild winters which have boosted overwinter their rivals. Each male will court any female survival. Monitoring work carried out by the that enters his territory, tempting her to use British Trust for Ornithology has highlighted one of the nests that he has built there. Males how particularly cold winters can reduce the nesting in the south of Britain will build five breeding population by a quarter or more. or six different nests, the female inspecting each in turn to determine which, if any, she The nesting habit wishes to use. Females appear to select nests The preferred nesting habitat of the Wren that are the most cryptic, presumably because is the understorey of deciduous and mixed such nests are less likely to be predated. -

House Wren Troglodytes Domesticus the House Wren Breeds Commonly

Wrens — Family Troglodytidae 419 House Wren Troglodytes domesticus The House Wren breeds commonly in San Diego County’s woodlands of oak, sycamore, and conifers, but here it is only beginning to take on the city- dwelling habits that justify its name over so much of the United States. Within its historic range, almost coextensive in San Diego County with that of the coast live oak, the wren has long patronized bird- houses as well as natural nest holes. But only since the 1990s has it spread into suburbs built over for- mer sage scrub. It is on the increase as a winter visi- tor or year-round resident too, possibly in response to climatic warming. Breeding distribution: The House Wren is widespread Photo by Anthony Mercieca on San Diego County’s coastal slope, most numerous in oak woodland and riparian woodland with large and possibly crevices behind loose strips of eucalyptus sycamores. It is common from low elevations (100 in bark for nest sites. The spread is going from north to Horno Canyon and along the south fork of San Onofre south. The largest concentration found in nonnative Creek, D3, 31 May 1998, K. Perry, D. Gould; 135 in Los habitat is in Pottery Canyon, La Jolla (P7), with up to 11 Peñasquitos and Lopez canyons, N8, 11 April 1999, P. on 27 May 1999 (L. and M. Polinsky). South of Mission A. Ginsburg et al.) to the higher mountains (13 near the Valley House Wrens are still uncommon through the summit of Hot Springs Mountain, E20, 18 June 2000, breeding season but probably nesting at Point Loma K. -

Troglodytidae Tree, Part I

Troglodytidae I ?Gray-mantled Wren, Odontorchilus branickii Tooth-billed Wren, Odontorchilus cinereus Canyon Wren, Catherpes mexicanus Salpinctinae Sumichrast’s Wren, Hylorchilus sumichrasti Nava’s Wren, Hylorchilus navai Rock Wren, Salpinctes obsoletus Nightingale Wren / Northern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus philomela Scaly-breasted Wren / Southern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus marginatus Flutist Wren, Microcerculus ustulatus Wing-banded Wren, Microcerculus bambla Pacific Wren, Nannus pacificus Winter Wren, Nannus hiemalis Eurasian Wren, Nannus troglodytes ?Zapata Wren, Ferminia cerverai Marsh Wren, Cistothorus palustris Sedge Wren, Cistothorus platensis ?Merida Wren, Cistothorus meridae Troglo dytinae ?Apolinar’s Wren, Cistothorus apolinari Timberline Wren, Thryorchilus browni Tepui Wren, Troglodytes rufulus Ochraceous Wren, Troglodytes ochraceus Mountain Wren, Troglodytes solstitialis ?Santa Marta Wren, Troglodytes monticola Rufous-browed Wren, Troglodytes rufociliatus Brown-throated Wren, Troglodytes brunneicollis Socorro Wren, Troglodytes sissonii ?Clarion Wren, Troglodytes tanneri Northern House-Wren, Troglodytes aedon Southern House-Wren, Troglodytes musculus ?Cozumel Wren, Troglodytes beani ?Cobb’s Wren, Troglodytes cobbi Bewick’s Wren, Thryomanes bewickii Carolina Wren, Thryothorus ludovicianus Thrush-like Wren, Campylorhynchus turdinus Stripe-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus nuchalis Band-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus zonatus Gray-barred Wren, Campylorhynchus megalopterus White-headed Wren, Campylorhynchus albobrunneus Fasciated