Conspecific Nest Aggression of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrestrial Ecology Enhancement

PROTECTING NESTING BIRDS BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR VEGETATION AND CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS Version 3.0 May 2017 1 CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 2.0 BIRDS IN PORTLAND 4 3.0 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF PORTLAND BIRDS 4 3.1 Timing 4 3.2 Nesting Habitats 5 4.0 GENERAL GUIDELINES 9 4.1 What if Work Must Occur During Avoidance Periods? 10 4.2 Who Conducts a Nesting Bird Survey? 10 5.0 SPECIFIC GUIDELINES 10 5.1 Stream Enhancement Construction Projects 10 5.2 Invasive Species Management 10 - Blackberry - Clematis - Garlic Mustard - Hawthorne - Holly and Laurel - Ivy: Ground Ivy - Ivy: Tree Ivy - Knapweed, Tansy and Thistle - Knotweed - Purple Loosestrife - Reed Canarygrass - Yellow Flag Iris 5.3 Other Vegetation Management 14 - Live Tree Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Snag Removal - Shrub Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Grassland Mowing and Ground Cover Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Controlled Burn 5.4 Other Management Activities 16 - Removing Structures - Manipulating Water Levels 6.0 SENSITIVE AREAS 17 7.0 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS 17 7.1 Species 17 7.2 Other Things to Keep in Mind 19 Best Management Practices: Avoiding Impacts on Nesting Birds Version 3.0 –May 2017 2 8.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND AN ACTIVE NEST ON A PROJECT SITE 19 DURING PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION? 9.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND A BABY BIRD OUT OF ITS NEST? 19 10.0 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR AVOIDING 20 IMPACTS ON NESTING BIRDS DURING CONSTRUCTION AND REVEGETATION PROJECTS APPENDICES A—Average Arrival Dates for Birds in the Portland Metro Area 21 B—Nesting Birds by Habitat in Portland 22 C—Bird Nesting Season and Work Windows 25 D—Nest Buffer Best Management Practices: 26 Protocol for Bird Nest Surveys, Buffers and Monitoring E—Vegetation and Other Management Recommendations 38 F—Special Status Bird Species Most Closely Associated with Special 45 Status Habitats G— If You Find a Baby Bird Out of its Nest on a Project Site 48 H—Additional Things You Can Do To Help Native Birds 49 FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1. -

IMBCR Report

Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR): 2015 Field Season Report June 2016 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies 14500 Lark Bunting Lane Brighton, CO 80603 303-659-4348 www.birdconservancy.org Tech. Report # SC-IMBCR-06 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies Connecting people, birds and land Mission: Conserving birds and their habitats through science, education and land stewardship Vision: Native bird populations are sustained in healthy ecosystems Bird Conservancy of the Rockies conserves birds and their habitats through an integrated approach of science, education and land stewardship. Our work radiates from the Rockies to the Great Plains, Mexico and beyond. Our mission is advanced through sound science, achieved through empowering people, realized through stewardship and sustained through partnerships. Together, we are improving native bird populations, the land and the lives of people. Core Values: 1. Science provides the foundation for effective bird conservation. 2. Education is critical to the success of bird conservation. 3. Stewardship of birds and their habitats is a shared responsibility. Goals: 1. Guide conservation action where it is needed most by conducting scientifically rigorous monitoring and research on birds and their habitats within the context of their full annual cycle. 2. Inspire conservation action in people by developing relationships through community outreach and science-based, experiential education programs. 3. Contribute to bird population viability and help sustain working lands by partnering with landowners and managers to enhance wildlife habitat. 4. Promote conservation and inform land management decisions by disseminating scientific knowledge and developing tools and recommendations. Suggested Citation: White, C. M., M. F. McLaren, N. J. -

Vocal Duetting Behaviour in a Neotropical Wren: Insights Into Paternity Guarding and Parental Commitment

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 10-5-2017 Vocal duetting behaviour in a neotropical wren: Insights into paternity guarding and parental commitment Zach Alexander Kahn University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Kahn, Zach Alexander, "Vocal duetting behaviour in a neotropical wren: Insights into paternity guarding and parental commitment" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 7268. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7268 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. VOCAL DUETTING BEHAVIOUR IN A NEOTROPICAL WREN: INSIGHTS INTO PATERNITY GUARDING AND PARENTAL COMMITMENT By ZACHARY ALEXANDER KAHN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of Biological Sciences in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2017 © Zachary A. -

First Documented Observation of Sedge Wren in Arizona Accepted

Arizona Birds - Journal of Arizona Field Ornithologists Volume 2011 FIRST DOCUMENTED OBSERVATION OF SEDGE WREN (Cistothorus platensis) IN ARIZONA Alan Schmierer, PO Box 626, Patagonia, AZ 85624 ([email protected]) Photos by the author. On 27 November 2010 the author discovered and photographed a Sedge Wren (Cistothorus platensis) on the shores of Peña Blanca Lake, Santa Cruz County, Arizona. This sighting was the first documented record of this species for Arizona. INITIAL DISCOVERY AND CONTINUED SIGHTINGS The initial discovery of this bird was a very brief encounter. At about mid-morning I was birding the south shore of the cove (informally called Thumb Rock Cove; see Figure 2) that is just north of the Upper Thumb Rock Picnic Area parking lot. Several double-chip notes, some- what reminiscent of those of the Pacific and Winter Wrens (Troglodytes pacificus and heimalis) alerted me to a potentially interesting bird be- ing present, followed by a 15 second look at the bird with binoculars (at about a two meter dis- tance), two quick photos (a lesson for photogra- phers to keep their cameras handy for such “bird emergencies”) and then the bird was gone. The wren was seen while it was about 1.5 m up in bare branches close to the trunk of a small deciduous tree at the water’s edge, and it then flew across the cove to a grassy edge of the op- posite shore. That brief view was enough for me to identify it as a Sedge Wren. Even as a new- comer to Arizona I knew that it was likely a very Figure 1: SEDGE WREN (27 November 2010) at initial sighting. -

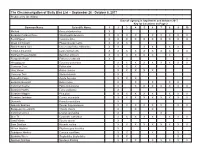

The Circumnavigation of Sicily Bird List -- September 26

The Circumnavigation of Sicily Bird List -- September 26 - October 8, 2017 Produced by Jim Wilson Date of sighting in September and October 2017 Key for Locations on Page 2 Common Name Scientific Name 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X Yellow-legged Gull Larus michahellis X X X X X X X X X X Northern House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X European Robin Erithacus rubecula X X Woodpigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X Common Coot Fulica atra X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X Bonnelli's Eagle Aquila fasciata X X X Eurasian Buzzard Buteo buteo X X X X X Common Kestrel Falco tinnunculus X X X X X X X X Eurasian Hobby Falco subbuteo X Eurasian Magpie Pica pica X X X X X X X X Eurasian Jackdaw Corvus monedula X X X X X X X X X Dunnock Prunella modularis X Spanish Sparrow Passer hispaniolensis X X X X X X X X European Greenfinch Chloris chloris X X X Common Linnet Linaria cannabina X X Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus X X X X X X X X Sand Martin Riparia riparia X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus X Subalpine Warbler Curruca cantillans X X X X Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes X X X Spotless Starling Spotless Starling X X X X X X X X Common Name Scientific Name 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sardinian Warbler Curruca melanocephala X X X X -

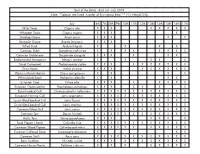

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Benton Lake National Wildlife

Glossary accessible—Pertaining to physical access to areas breeding habitat—Environment used by migratory and activities for people of different abilities, es- birds or other animals during the breeding sea- pecially those with physical impairments. son. A.D.—Anno Domini, “in the year of the Lord.” canopy—Layer of foliage, generally the uppermost adaptive resource management (ARM)—The rigorous layer, in a vegetative stand; mid-level or under- application of management, research, and moni- story vegetation in multilayered stands. Canopy toring to gain information and experience neces- closure (also canopy cover) is an estimate of the sary to assess and change management activities. amount of overhead vegetative cover. It is a process that uses feedback from research, CCP—See comprehensive conservation plan. monitoring, and evaluation of management ac- CFR—See Code of Federal Regulations. tions to support or change objectives and strate- CO2—Carbon dioxide. gies at all planning levels. It is also a process in Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)—Codification of which the Service carries out policy decisions the general and permanent rules published in the within a framework of scientifically driven ex- Federal Register by the Executive departments periments to test predictions and assumptions and agencies of the Federal Government. Each inherent in management plans. Analysis of re- volume of the CFR is updated once each calendar sults helps managers decide whether current year. management should continue as is or whether it compact—Montana House bill 717–Bill to Ratify should be modified to achieve desired conditions. Water Rights Compact. alternative—Reasonable way to solve an identi- compatibility determination—See compatible use. -

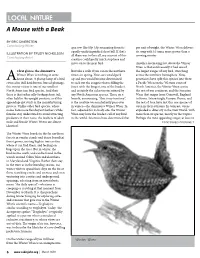

A Mouse with a Beak

LOCAL NATURE A Mouse with a Beak BY ERIC DINERSTEIN Contributing Writer sparrow-like klip-klip emanating from its per unit of weight, the Winter Wren delivers equally undistinguished short bill. If that’s its song with 10 times more power than a ILLUSTRATION BY TRUDY NICHOLSON all there was to the call, my account of this crowing rooster. Contributing Artist creature could pretty much stop here and move on to the next bird. Another fascinating fact about the Winter Wren is that until recently it had one of t frst glance, the diminutive But take a walk if you can in the northern the largest ranges of any bird, stretching Winter Wren is nothing to write forests in spring. Your ears would perk across the northern hemisphere. Now, home about. A plump lump of a bird up and you would become determined geneticists have split this species into three: Acovered in dull dark brown, barred plumage, to seek out the songster that is flling the a Pacifc Wren on the Western coast of this winter visitor is one of our smallest forest with the longest, one of the loudest, North America, the Winter Wren across North American bird species. And then and certainly the richest notes uttered by the rest of our continent, and the Eurasian there is that rather silly-looking short tail, any North American species. Tere on a Wren that ranges from Cornwall, England ofen held in the upright position, as if this branch, announcing, “this is my territory”, to Korea. Interestingly, Europe, Russia, and appendage got stuck in the manufacturing is the creature we nonchalantly pass over the rest of Asia have just this one species of process. -

Natal and Breeding Dispersal in House Wrens (Troglodytes Aedon)

NATAL AND BREEDING DISPERSAL IN HOUSE WRENS (TROGLODYTES AEDON) NANCY E. DRILLING AND CHARLES F. THOMPSON EcologyGroup, Department of BiologicalSciences, IllinoisState University,Normal, Illinois 61761 USA ABSTRACT.--Westudied the natal and breeding dispersalof yearling and adult HouseWrens (Troglodytesaedon) for 7 yr in central Illinois. The forestedstudy areascontained 910 identical nest boxesplaced in a grid pattern. On average38.1% (n = 643) of the adult malesand 23.3% (n = 1,468) of the adult females present in one year returned the next; 2.8% (n = 6,299) of the nestlingsthat survived to leave the nest returned eachyear. Adult male (median distance = 67 m) and adult female (median = 134 m) breeding dispersalwas lessthan yearling male (median = 607.5 m) and yearling female (median = 674 m) natal dispersal.Females that returned had producedmore offspringthe previousseason than had nonreturningfemales, and femalesthat successfullyproduced at leastone chick in their last nesting attempt of the previousseason moved shorter distances than did unsuccessfulfemales. There were, however, no consistentdifferences between returning and nonreturning femalesin two other measures of reproductivesuccess. Females that were unsuccessfulin their lastbreeding attempt of the previousyear were more likely to be successfulin their next attempt if they moved two or more territoriesthan if they did not move. Reproductivesuccess did not affectthe likelihood that a male would return nor the distancethat he moved.The successof subsequentnesting attemptsby maleswas -

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2016-C No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark 02 06 Recognize Lilian’s Meadowlark Sturnella lilianae as a separate species from S. magna 03 20 Change the English name of Euplectes franciscanus to Northern Red Bishop 04 25 Transfer Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis to Antigone 05 29 Add Rufous-necked Wood-Rail Aramides axillaris to the U.S. list 06 31 Revise our higher-level linear sequence as follows: (a) Move Strigiformes to precede Trogoniformes; (b) Move Accipitriformes to precede Strigiformes; (c) Move Gaviiformes to precede Procellariiformes; (d) Move Eurypygiformes and Phaethontiformes to precede Gaviiformes; (e) Reverse the linear sequence of Podicipediformes and Phoenicopteriformes; (f) Move Pterocliformes and Columbiformes to follow Podicipediformes; (g) Move Cuculiformes, Caprimulgiformes, and Apodiformes to follow Columbiformes; and (h) Move Charadriiformes and Gruiformes to precede Eurypygiformes 07 45 Transfer Neocrex to Mustelirallus 08 48 (a) Split Ardenna from Puffinus, and (b) Revise the linear sequence of species of Ardenna 09 51 Separate Cathartiformes from Accipitriformes 10 58 Recognize Colibri cyanotus as a separate species from C. thalassinus 11 61 Change the English name “Brush-Finch” to “Brushfinch” 12 62 Change the English name of Ramphastos ambiguus 13 63 Split Plain Wren Cantorchilus modestus into three species 14 71 Recognize the genus Cercomacroides (Thamnophilidae) 15 74 Split Oceanodroma cheimomnestes and O. socorroensis from Leach’s Storm- Petrel O. leucorhoa 2016-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 453 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark There are a dizzying number of larks (Alaudidae) worldwide and a first-time visitor to Africa or Mongolia might confront 10 or more species across several genera. -

Troglodytes Troglodytes

Troglodytes troglodytes -- (Linnaeus, 1758) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PASSERIFORMES -- TROGLODYTIDAE Common names: Winter Wren; Wren European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) In Europe this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend appears to be stable, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. Within the EU27 this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). Despite the fact that the population trend appears to be decreasing, the decline is not believed to be sufficiently rapid to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in the EU27. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Albania; Andorra; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Faroe Islands (to DK); Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iceland; Ireland, Rep. -

House Wren Nest-Destroying Behavior’

The Condor 88:190-193 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1986 HOUSE WREN NEST-DESTROYING BEHAVIOR’ JEAN-CLAUDE BELLES-ISLES AND JAROSLAV PICMAN Department of Biology, Universityof Ottawa, Ottawa KIN 6N5, Canada Abstract. House Wren (Troglodytesaedon) nest-destroying behavior was studied by experi- mentally offering 38 wrens nestswith eggs(or nestlings)throughout the nesting season.Individuals of both sexespecked all six types of eggspresented, regardless of the nest type and location. House Wrens also attacked conspecificyoung. Older nestlings(nine days old) were less vulnerable than three-day-old young. Our resultssuggest that nest-destroyingbehavior is inherent in all adult House Wrens but is inhibited in mated males and breeding females. It is suggestedthat nest destruction may have evolved as an interference mechanism reducing intra- and interspecific competition. Key words: House Wren; Troglodytes aedon; infanticide;nest destruction; competition. INTRODUCTION specificnestlings? (3) Is this behavior exhibited Destruction of eggs by small passerinesis a throughout the breeding season?(4) Do indi- relatively rare phenomenon which has been vidual House Wrens destroy neststhroughout observed mainly in members of two families, their breeding cycle? (5) How widespread is the Troglodytidae and Mimidae. Species this behavior among individuals from a pop- known to destroy eggsinclude the Marsh Wren ulation? (6) Is this behavior a local phenom- (Cistothoruspalustris; Allen 19 14); House enon or is it characteristic of all House Wren Wren (Troglodytesaedon; Sherman 1925, populations?(7) What is the adaptive value of Kendeigh 194 1); Cactus Wren (Campylorhyn- this behavior? thusbrunneicapillus; Anderson and Anderson METHODS 1973); SedgeWren (Cistothorusplatensis; Pic- man and Picman 1980); Bewick’s Wren This study was conducted at Presqu’ile Pro- (Thryomanesbewickii; J.