Staff Faculty Funding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'James Cameron's Story of Science Fiction' – a Love Letter to the Genre

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad April 27 - May 3, 2018 A S E K C I L S A M M E L I D 2 x 3" ad D P Y J U S P E T D A B K X W Your Key V Q X P T Q B C O E I D A S H To Buying I T H E N S O N J F N G Y M O 2 x 3.5" ad C E K O U V D E L A H K O G Y and Selling! E H F P H M G P D B E Q I R P S U D L R S K O C S K F J D L F L H E B E R L T W K T X Z S Z M D C V A T A U B G M R V T E W R I B T R D C H I E M L A Q O D L E F Q U B M U I O P N N R E N W B N L N A Y J Q G A W D R U F C J T S J B R X L Z C U B A N G R S A P N E I O Y B K V X S Z H Y D Z V R S W A “A Little Help With Carol Burnett” on Netflix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) (Carol) Burnett (DJ) Khaled Adults Place your classified ‘James Cameron’s Story Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 (Taraji P.) Henson (Steve) Sauer (Personal) Dilemmas ad in the Waxahachie Daily Merchandise High-End (Mark) Cuban (Much-Honored) Star Advice 2 x 3" ad Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and Deal Merchandise (Wanda) Sykes (Everyday) People Adorable Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search (Lisa) Kudrow (Mouths of) Babes (Real) Kids of Science Fiction’ – A love letter Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item © Zap2it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 to the genre for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light,3.5" ad “AMC Visionaries: James Cameron’s Story of Science Fiction,” Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post premieres Monday on AMC. -

Residents Struggling to Carve out a New Life Amid Michael's Devastation

CAUTION URGED FOR INSURANCE CLAIMS LOCAL | A3 PANAMA CITY SPORTS | B1 BUCKS ARE BACK Bozeman carries on, will host South Walton Tuesday, October 23, 2018 www.newsherald.com @The_News_Herald facebook.com/panamacitynewsherald 75¢ Radio crucial Step by step after Cat 4 storm When newer technologies failed, radio worked following Hurricane Michael’s devastation By Ryan McKinnon GateHouse Media Florida PANAMA CITY — In the hours following one of the biggest news events in Bay County history, residents had little to no access to news. Hurricane Michael’s 155 mile-per-hour winds had toppled power lines, television satel- lites, radio antennas and crushed newspaper offices. Cellphones were useless across much of the county with spotty- at-best service and no access to internet. It was radio static across the radio dial, Peggy Sue Singleton salvages from the ruins of her barbershop a sign that used to show her prices. Only a few words are now legible: “This is the happy place.” [KEVIN BEGOS/THE WASHINGTON POST] See RADIO, A2 Residents struggling to carve out a new life amid Michael’s devastation By Frances Stead strewn across the parking lot Hurricane Michael was the reliable cellphone service and Sellers, Kevin Begos as if bludgeoned by a wreck- wrecker of this happy place. access to the internet. and Katie Zezima ing ball, her parlor a haphazard It hit here more than a week This city of 36,000 long has The Washington Post heap of construction innards: ago, with 155-mph winds that been a gateway to the Gulf, LOCAL & STATE splintered wood, smashed ripped and twisted a wide a white-beach playground A3 PANAMA CITY — Business windows, wire. -

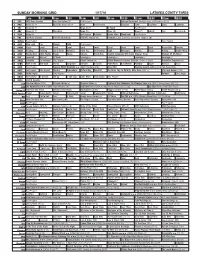

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Clangers Luna! LazyTown Luna! LazyTown 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Liberty Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song Motown 25 My Music 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Race to Witch Mountain ›› (2009, Aventura) (PG) Zona NBA Treasure Guards (2011) Anna Friel, Raoul Bova. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

JOCELYN M. RICHARD Derek Van Pelt/Mainstay Entertainment [email protected] / (978) 621-9962 / Jocelynrichard.Net

JOCELYN M. RICHARD Derek Van Pelt/Mainstay Entertainment [email protected] / (978) 621-9962 / jocelynrichard.net WRITING RESUME My Next Guest Needs No Introduction with David Letterman, Netflix, 2020 (consulting producer) Worked with host and executive producers on Season 3 of hourlong interview series. Lights Out with David Spade, Co medy Central, 2020 (writer) Staff writer on half-hour late night show hosted by David Spade. Crank Yankers, Comedy Central, 2019 (writer) Staff writer for half-hour crank? show. Liza On Demand, YouTube Digital, 2019 (executive story editor) Served as Executive Story Editor on Season 2 of half-hour narrative comedy. The Rose Parade with Cord and Tish, multiple platforms, 2019 (writer/consulting producer) Wrote sketches and promos and produced segments and field pieces for live special starring Will Ferrell and Molly Shannon. The Royal Wedding Live! with Cord and Tish, HBO, 2018 (writer/consulting producer) Wrote sketches and promos and produced segments and field pieces for live special starring Will Ferrell and Molly Shannon. I Love You, America with Sarah Silverman, Hulu, 2016-2018 (writer) Wrote monologues, sketches, and field pieces for half-hour topical late night show. Our Cartoon President, Showtime, 2017-2018 (staff writer) Served as Staff Writer on half-hour animated comedy. Also wrote promos and cold opens and directed actors. Funny or Die, FunnyorDie.com, 2015-2016 (staff writer) Served on staff writing and producing sketches and working with celebrity talent. The High Court with Doug Benson, Comedy Central, 2016 (writer) Wrote for half-hour courtroom parody late night show. @midnight with Chris Hardwick, Comedy Central, 2015-2016 (writer) Wrote monologue jokes and game segments and prepped talent for late night show. -

ALPINE SUN -� Best Climate, in US by Government Report Vol

America's Tinest Newspaper � �ALPINE SUN -� Best Climate, in US by Government Report Vol. 18 No, 12 Alpine, Calif. 92001 Friday, Mar. 21, 1969 10¢ YOUNGSTERS SHOW MUCH TA LENT COUPLE BUYS KING MEAT BUSINESS March's art exhibit at the library . Doug Benson and his wife Peggy have belongs to the young, young generation, Just bought out King Meat Processing, and it shows much talent. The arts and 2358 Tavern Road. Sale included the crafts were done by Mrs. Sparke's class nice 3-bedroom home where they are at the Canyon school, paintings by the �iving with their two youngsters, Doug, Eberle children, and stitchery oy Mrs. Jr., 8, a 3rd grader here, and Mickie Fletcher's class here. Lynne, 5, going to kindergarten. Photo shows, from left, front row: The meat business and house are on Denise Armbruster, Clare Wooley, Jef- 3,2 acres, Benson has changed the name fry Peterson, Robin Lipetsky, Bonnie to Alpine Meat Co, They lived in Flet· _Vail and Patty Hodge: top row: Deniel cher Hills. He was formerly with Safe· 1 . { � * K··-, ....r , 'I , a www :::Ii ; : -w-• I _,. ,. J 1 Espinoza, Mary Wooldridge, Robbie way. Benson's father is a veteran de Lovett, Danetta Luknow & Russell Lip· tective on the EC police force, and etsky. works as assistant manager of the El Says Elizabeth West, librarian, who Cajon Theatre with Tom Gapen. stages these monthly art shows: "our boys and girls have spent many hours getting this exhibit ready and it has NEW SEWER PLAN LOOKS GOOD oeen rated by county art consultants as Wednesday night the chamber of com being some of the finest art work done merce was to discuss the new sanitation by diildren in the SD county schools. -

MC5697-42.Qxd

MAYO CLINIC HEALTH POLICY CENTER A sampling of participants James Andrews, F.S.A., E.A. Doug Benson James Blumstein, L.L.B., M.A. Watson Wyatt Minnesota Department of Health Vanderbilt University Joseph Antos, Ph.D. James Berarducci Bruce Bradley, M.B.A. American Enterprise Institute Kurt Salmon Associates General Motors Corporation Howard H. Baker Jr. Robert Berenson, M.D. David Bronson, M.D. Baker, Donelson, Bearman, Caldwell Urban Institute Cleveland Clinic & Berkowitz, PC Donald Berwick, M.D. Emily Burge David Barrett, M.D. Institute for Healthcare Juvenile Diabetes Research Lahey Clinic Improvement Foundation George Bartley, M.D. Michael Birt, Ph.D. Steve Burrows, M.B.A., M.P.H. Mayo Clinic The National Bureau of Asian Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota Research George Bennett Stuart Butler, Ph.D. Health Dialog RADM Susan Blumenthal, M.D. The Heritage Foundation Georgetown University School of Medicine John Butterly, M.D. Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center Marilyn Carlson Nelson Carlson Companies Michael Cascone Jr. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Florida Steve Case Revolution Health Carolyn Clancy, M.D. Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality Jon Comola Wye River Group on Healthcare Steve Lampkin, Wal-Mart; Jerome Grossman, M.D., Harvard; and Michael Morrow, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota Marcia Comstock, M.D., M.P.H. Comstock Consulting Group, LLC Ensuring the future of quality patient care MAYO CLINIC HEALTH POLICY CENTER PARTICIPANTS Colleen Conway-Welch, Ph.D., R.N., Donald Fisher, Ph.D. David Helms, Ph.D. F.A.A.N. American Medical Group Association AcademyHealth Vanderbilt University School of Nursing Elliott Fisher, M.D., M.P.H. -

COMEDY CENTRAL Records(R) to Release Doug Benson's 'Unbalanced Load' CD on Tuesday, August 4

COMEDY CENTRAL Records(R) to Release Doug Benson's 'Unbalanced Load' CD on Tuesday, August 4 NEW YORK, July 27 -- Take a load off and catch Doug Benson's new CD "Unbalanced Load" released on COMEDY CENTRAL Records August 4. "Unbalanced Load" was recorded at the Punchline in San Francisco on April 20th, 2009. Why that date? Not because it's Hitler's birthday, but because 4/20 has been adopted as a stoner holiday and Benson is one of the biggest pot comics around. He co-wrote the Off-Broadway show (and COMEDY CENTRAL Records release) "The Marijuana-Logues" and starred in the documentary "Super High Me," in which he smoked pot continuously for 30 days. Benson is best known for his regular appearances on VH1's "Best Week Ever" and was a finalist on NBC's "Last Comic Standing." His television appearances also include a "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents" half-hour special in January 2009 and appearances on "Jimmy Kimmel Live," "The Sarah Silverman Program," "Curb Your Enthusiasm" and "Friends." In addition to his credits as creator/writer/star of "The Marijuana-Logues," a show that's been a hit in clubs and theatres from Los Angeles to New York, drawing a bongload of rave reviews and his COMEDY CENTRAL CD, he also authored a book, The Marijuana- Logues: Everything About Pot That We Could Remember. In 2006, High Times Magazine named him Stoner of the Year. Doug also expresses his love of movies on his "I Love Movies" podcasts (available on iTunes). Previously released recordings by COMEDY CENTRAL Records include: Dane Cook's "ISolated INcident," Cook's -

The Ucsd Ari)

HIATUS Brier.. A.S. Council update A Jolly good time Opinion letter to the Editor 6 UCSD loses in A sneak peak into the life of an international prankster. 'Trigger conference final Happy TV' host Dom Jolly reveals his inspiration, his favorite beer lhundlV Coupons 11 Loyola Marymount and what makes him tick. page 9 Classifieds 16 University. page 20 THE UCSD ARI) UC SAN DIEGO THURSDAY, MAY 1, 2003 VOLUME 109, ISSUE 1& Los Alamos EAP students Hot off the grill contrad return from China will go to SARS scare initiated recall of highest bid 43 who were studying abroad By EVAN McLAUGHUN blings of government cover-ups" News Editor regarding the reponed severi ty University of of MS. A professor at Peking Forty-three OIversity of Ul1Iver I!y, one of the EAP host California Califorllla student returned universities in Beijing, had also from China last week after the been recently diagnosed with the must compete University suspended its disea e. Educaoon broad Program In " We had communica ti ons for jon Beipng following the increa 109 with twO UC sta ffers, both of outbreak of evcre Acute whom fel t that the SlnlatJon had By THOMAS NEELEY Respi racory Syndrome In the deteriorated to the pOint where regIon. they no longer felt it was safe for Senior Staff Writer ne student has decided co the tudents to remain," said Ending several months of stay In BeiJIng, and as a result has EAP poke person Bruce Ilanna. peculation, Energy Secretary Withdrawn from the Univer ity UC officials noofied students Spencer Abraham announced on of California, an EAP spokesper enrolled in EAP Beijing on April April 30 that the contract to man son said. -

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD 15 20795 Those Who Wish Me Dead 2021 DVD 15 20794 The Father 2020 DVD 12 20793 A Quiet Place Part 2 2020 DVD 15 20792 Cruella 2021 DVD 12 20791 Luca 2021 DVD U 20790 Five Feet Apart 2019 DVD 12 20789 Sound of Metal 2019 BR 15 20788 Promising Young Woman 2020 DVD 15 20787 The Mountain Between Us 2017 DVD 12 20786 The Bleeder 2016 DVD 15 20785 The United States Vs Billie Holiday 2021 DVD 15 20784 Nomadland 2020 DVD 12 20783 Minari 2020 DVD 12 20782 Judas and the Black Messiah 2021 DVD 15 20781 Ammonite 2020 DVD 15 20780 Godzilla Vs Kong 2021 DVD 12 20779 Imperium 2016 DVD 15 20778 To Olivia 2021 DVD 12 20777 Zack Snyder's Justice League 2021 DVD 15 20776 Raya and the Last Dragon 2021 DVD PG 20775 Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar 2021 DVD 15 20774 Chaos Walking 2021 DVD 12 20773 Treacle Jr 2010 DVD 15 20772 The Swordsman 2020 DVD 15 20771 The New Mutants 2020 DVD 15 20770 Come Away 2020 DVD PG 20769 Willy's Wonderland 2021 DVD 15 20768 Stray 2020 DVD 18 20767 County Lines 2019 BR 15 20767 County Lines 2019 DVD 15 20766 Wonder Woman 1984 2020 DVD 12 20765 Blackwood 2014 DVD 15 20764 Synchronic 2019 DVD 15 20763 Soul 2020 DVD PG 20762 Pixie 2020 DVD 15 20761 Zeroville 2019 DVD 15 20760 Bill and Ted Face the Music 2020 DVD PG 20759 Possessor 2020 DVD 18 20758 The Wolf of Snow Hollow 2020 DVD 15 20757 Relic 2020 DVD 15 20756 Collective 2019 DVD 15 20755 Saint Maud 2019 DVD 15 20754 Hitman Redemption 2018 DVD 15 20753 The Aftermath 2019 DVD 15 20752 Rolling Thunder Revue 2019 -

Baylor Slams OU 41-12

10 SPORTS p. 9 baylorlariat com No. 5 Baylor soccer takes on No. 1 seed West Virginia on the road today. Baylor Lariat WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE Friday | November 8, 2013 Boomer Loser TWITTER from Page 1 By Daniel Hill After a 3-0 Oklahoma lead in a rough first was a lot of hype and the fans were wonderful to- Sports Editor quarter filled with immense intensity between two night. We owe a lot to them. They were loud. Going ranked teams, the Bears asserted themselves by fin- into this game, it was kind of our first time to have Baylor After seven games without a true test on the ishing the game in dominant fashion and outscor- a true test as far as the whole hype of the situation gridiron, the Baylor Bears were supposed to be ing the Sooners 38-12 in the final three quarters for a big game like that.” challenged by the No. 10 Oklahoma Sooners, the of the game. In a game where the Bears needed to Before the game even started, the energy-in- first ranked opponent for Baylor this season. The make a national statement to advance in the BCS fused crowd at Floyd Casey Stadium was ready for No. 6 Bears answered the call and more by thump- standings, the Bears left no doubt with a 29-point a battle royal between two Big 12 juggernauts. In slams ing Oklahoma 41-12 in front of 50,537 fans decked victory over the No. 10 team in the land. -

Banksy. Urban Art in a Material World

Ulrich Blanché BANKSY Ulrich Blanché Banksy Urban Art in a Material World Translated from German by Rebekah Jonas and Ulrich Blanché Tectum Ulrich Blanché Banksy. Urban Art in a Material World Translated by Rebekah Jonas and Ulrich Blanché Proofread by Rebekah Jonas Tectum Verlag Marburg, 2016 ISBN 978-3-8288-6357-6 (Dieser Titel ist zugleich als gedrucktes Buch unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-3541-2 im Tectum Verlag erschienen.) Umschlagabbildung: Food Art made in 2008 by Prudence Emma Staite. Reprinted by kind permission of Nestlé and Prudence Emma Staite. Besuchen Sie uns im Internet www.tectum-verlag.de www.facebook.com/tectum.verlag Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Angaben sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Table of Content 1) Introduction 11 a) How Does Banksy Depict Consumerism? 11 b) How is the Term Consumer Culture Used in this Study? 15 c) Sources 17 2) Terms and Definitions 19 a) Consumerism and Consumption 19 i) The Term Consumption 19 ii) The Concept of Consumerism 20 b) Cultural Critique, Critique of Authority and Environmental Criticism 23 c) Consumer Society 23 i) Narrowing Down »Consumer Society« 24 ii) Emergence of Consumer Societies 25 d) Consumption and Religion 28 e) Consumption in Art History 31 i) Marcel Duchamp 32 ii) Andy Warhol 35 iii) Jeff Koons 39 f) Graffiti, Street Art, and Urban Art 43 i) Graffiti 43 ii) The Term Street Art 44 iii) Definition