Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

The Long Red Thread How Democratic Dominance Gave Way to Republican Advantage in Us House of Representatives Elections, 1964

THE LONG RED THREAD HOW DEMOCRATIC DOMINANCE GAVE WAY TO REPUBLICAN ADVANTAGE IN U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTIONS, 1964-2018 by Kyle Kondik A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Baltimore, Maryland September 2019 © 2019 Kyle Kondik All Rights Reserved Abstract This history of U.S. House elections from 1964-2018 examines how Democratic dominance in the House prior to 1994 gave way to a Republican advantage in the years following the GOP takeover. Nationalization, partisan realignment, and the reapportionment and redistricting of House seats all contributed to a House where Republicans do not necessarily always dominate, but in which they have had an edge more often than not. This work explores each House election cycle in the time period covered and also surveys academic and journalistic literature to identify key trends and takeaways from more than a half-century of U.S. House election results in the one person, one vote era. Advisor: Dorothea Wolfson Readers: Douglas Harris, Matt Laslo ii Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………....ii List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………..iv List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………..v Introduction: From Dark Blue to Light Red………………………………………………1 Data, Definitions, and Methodology………………………………………………………9 Chapter One: The Partisan Consequences of the Reapportionment Revolution in the United States House of Representatives, 1964-1974…………………………...…12 Chapter 2: The Roots of the Republican Revolution: -

153682NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. .. .; J , ..~. .;"~ • .' ~ .~ _... '> .' UJ.l.IU.ll Calendar No. 605 102n CONGRESS REPORT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 2d Session 102-1070 • ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1991 REPORT OF THE • SELECT COMMITTEE ON NARCOTICS ABUSE AND CONTROL ONE HUNDRED SECOND CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SCNAC-102-1-14 N'CJRS ACQUISITKON,; Printed for the use of the Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control U.s. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE • o WASHINGTON : 1992 :au • SELECI' COMMITTEE ON NARCOTICS ABUSE AND CONTROL (102D CoNGRESS) CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York, Chairman JACK BROOKS, Texas LAWRENCE COUGHLIN, Pennsylvania FORTNEY H. (PETE) STARK, California BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York JAMES H. SCHEUER, New York MICHAEL G. OXLEY, Ohio CARDISS COLLINS, TIlinois F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., FRANK J. GUARINI, New Jersey Wisconsin DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida ROBERT K. DORNAN, California WILLIAM J. HUGHES, New Jersey TOM LEWIS, Florida • MEL LEVINE, California JAMES M. INHOFE, Oklahoma SOWMON P. ORTIZ, Texas WALLY HERGER, California LAWRENCE J. SMITH, Florida CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut EDOLPHUS "ED" TOWNS, New York BILL PAXON, New York JAMES A. TRAFICANT, JR., Ohio WILLIAM F. CLINGER, JR., Pennsylvania KWEISI MFUME, Maryland HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina NITA M. WWEY, New York PAUL E. GILLMOR, Ohio DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey JIM RAMSTAD, Minnesota ROMANO L. MAZZOLI, Kentucky RON DE LUGO, Virgin Islands GEORGE J. HOCHBRUECKNER, New York CRAIG A. WASHINGTON, Texas ROBERT E. ANDREWS, New Jersey COMMI'ITEE STAFF EDWARD H. JURlTH, Staff Director P&'rER J. CoNIGLIO, Minority Staff Director (Ill 153682 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice . -

Extensions of Remarks Hon.Henryj.Nowak

March 24, 1982 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 5419 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS PORT USER-FEE PLANS REQUIRE harbor would be 1.7 cents, Duluth-Su Kudrna, chairman of the commission, MORE STUDY perior's 1.4 cents, Toledo's 3.2 cents, testified: and New York-New Jersey 2.7 cents. We do not believe that the impacts of the That type of disparity raises serious proposed deepdraft fees have been studied HON.HENRYJ.NOWAK questions about the potential impact in sufficient detail. Without better impact OF NEW YORK on traffic diversion from port to port information it seems to the GLC that we IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES or to other modes of transport. Even are sailing into a storm without a navigation system. Wednesday, March 24, 1982 'more basic is the question of the po tential adverse impact any port user e Mr. NOWAK. Mr. Speaker, among Following are 13 areas the GLC sug fee would have on ports like Buffalo's, gested for detailed analysis: the administration's proposals for re which deal heavily in bulk cargo for ducing Federal expenditures is a plan the hard-pressed auto, steel, and grain THE 13 AREAs SUGGESTED BY GLC to establish a system of user fees that would shift the financial responsibility milling industries. 1. DOUBLE CHARGES FOR DOMUTIC FREIGHT for harbor maintenance and improve The seriousness of those questions Application of charges directly by each ments from the Federal Government are compounded when one considers port may cause domestic freight to incur a to the deepwater ports. that the administation is also propos double charge-one at the origin and one at ing a separate user-fee plan to recoup the destination ports. -

Campaign Trips (4)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 32, folder “Campaign Trips (4)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 32 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library i MO:i\JJA Y - NOVEMBER I, 1976 AKRON-CANTON, OHIO ! E vent No. 1 RALLY- Firestone Hangar, 1 Akron- c~nton Airport. REMARKS. COLUMBUS, OHIO Event No. 2 RALLY - State Capitol Steps. REMARKS. Event No. 3 Drop-By Fort Hayes Career Center. Visit various work/training labs. REMARKS to Student Body. LIVONIA, MICHIGAN ' . Event No. 4 RALLY - Wonderland Center (Shopping Mall) - REMARKS. GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN Event No. 5 WELCOMING PARADE. Event No. 6 Dedication o£ the Gerald R. Ford Health and Physical Education Building at Grand Rapids Junior C~llege. REMARKS. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON CAMPAIGN SWING AKRON-CANTON, OHIO COLUMBUS, OHIO LIVONIA, MICHIGAN GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MONDAY- NOVEMBER 1, 1976 DAY# 10 First Event: 9:45A.M. -

Results-Summary-Gen06 (PDF)

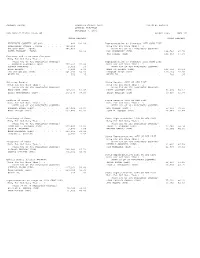

SUMMARY REPORT FRANKLIN COUNTY OHIO OFFICIAL RESULTS GENERAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 7, 2006 RUN DATE:11/29/06 08:45 AM REPORT-EL45 PAGE 001 VOTES PERCENT VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 842). 842 100.00 Representative to Congress 12TH CONG DIST REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 766,652 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 385,863 (WITH 367 OF 367 PRECINCTS COUNTED) VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 50.33 BOB SHAMANSKY (DEM) . 108,746 42.70 PAT TIBERI (REP) . 145,943 57.30 Governor and Lieutenant Governor (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (WITH 835 OF 835 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Representative to Congress 15TH CONG DIST J. KENNETH BLACKWELL (REP). 122,601 32.80 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 ROBERT FITRAKIS . 3,703 .99 (WITH 434 OF 434 PRECINCTS COUNTED) BILL PEIRCE. 5,382 1.44 MARY JO KILROY (DEM). 109,659 49.58 TED STRICKLAND (DEM). 241,536 64.62 DEBORAH PRYCE (REP) . 110,714 50.06 WRITE-IN. 553 .15 WRITE-IN. 783 .35 Attorney General State Senator 03RD OH SEN DIST (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (WITH 835 OF 835 PRECINCTS COUNTED) (WITH 316 OF 316 PRECINCTS COUNTED) MARC DANN (DEM) . 187,191 51.07 DAVID GOODMAN (REP) . 71,874 54.12 BETTY MONTGOMERY (REP) . 179,370 48.93 EMILY KREIDER (DEM) . 60,927 45.88 Auditor of State State Senator 15TH OH SEN DIST (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (WITH 835 OF 835 PRECINCTS COUNTED) (WITH 251 OF 251 PRECINCTS COUNTED) BARBARA SYKES (DEM) . -

Appendix File 1982 Merged Methods File

Page 1 of 145 CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1982 MERGED METHODS FILE USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> ABOUT THE EXPRESSIONS IN THE 1982 QUESTIONNAIRE (NAME Y X, Y. OR Z) The 1982 tIME sERIES questionnaire made provisions to have interviewers fill in district/state candidate names in blank slots like the one depicted above. A comprehensive list of HOUSE, SENATE and GOVERNOR candidate and incumbent names was prepared for each of the 173 districts in the sample and the interviewers used the lists to pre-edit names where appropriate depending on the district of interview. These candidate lists are reproduced in the green pages section of this documentation. The (NAME #) expression will generally list more than one candidate number. For any given district, however, one of two possibilities will hold: 1) there will be one and only one name in the district candidate list qualifying for inclusion on the basis of the numbers listed in the expression; or 2) there will be no number in the district candidate list matching any of the numbers in the expression. An instance of no matching numbers arises for a question about the candidate challenging a district incumbent when, in fact, the incumbent is running unopposed. Interviewers were instructed to mark "NO INFO" those questions involving unmatched candidate numbers in the (NAME #) expression. In the candidate list, each candidate or incumbent is assigned a number or code. Numbers beginning with 1 (11-19) are for the Senate, numbers beginning with 3 (31-39) are for the House of Representatives, and numbers beginning with 5 (51-58) are for governors. -

THUMB'' EVENT BRIEF the AREA: Almost Entirely Agricultural. The

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu MICHIGAN "THUMB'' EVENT BRIEF THE AREA: Almost entirely agricultural. The chief products in the area are navy beans (USED IN SENATE BEAN SOUP) sugar beets and corn. Sanilac County has a higher degree of dairy farming than Tuscola or Huron. THE ISSUES: The chief issue in the "thumb" is the farm crisis. The price of land is down. Farmers are receiving low prices for farm products. Production costs are high. Farm implement dealers are also in an economic crisis. A recent survey of agricultural bankers showed that the dollar values of ''good" farmland in Michigan's Lower Peninsula, which includes the Thumb, showed a 3 percent drop in the first quarter of 1986. The survey also indicated that the 3 percent decline in the first quarter compares to a 10 percent decline for the past year from April '85 to April '86. The survey confirms that the rate of decline in farmland values has slowed. The survey of 500 agricultural bankers was conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank's Chicago-based Seventh district. The district includes Michigan, Indiana, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Illinois. THE POLITICS: About 500 precinct delegate candidates from Huron, Tuscola, and Sanilac counties will attend tonight's fundraiser. About 350 precinct delegates will be elected from the Thumb area. Many delegate candidates have not made up their minds as to which presidential candidate they prefer. Many, since this is a heavy agricultural area, are waiting to hear you before they make a decision. -

Current Situation in Namibia

Current Situation in Namibia http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.uscg013 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Current Situation in Namibia Alternative title Current Situation in Namibia Author/Creator Subcommittee on Africa; Committee on Foreign Affairs; House of Representatives Publisher U.S. Government Printing Office Date 1979-05-07 Resource type Hearings Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Namibia, United States Source Congressional Hearings and Mission Reports: U.S. Relations with Southern Africa Description Witness is Donald F. McHenry, Deputy U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. Hearing is chaired by Stephen J. -

Appendix File 1987 Pilot Study (1987.Pn)

Page 1 of 189 Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1987 PILOT STUDY (1987.PN) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> OPEN-END RESPONSES FOR THE 1987 PILOT WAVES 1 AND 2 N.B. 1. The first part of this section is a memo by John Zaller, "Cognitive Responses to Survey Questions" which documents and discusses the coding scheme for the cognitive experiments on the Pilot Study. Those who plan to use these data should, without fail, read this memo. 2. The Zaller memo is followed by the open-end master codes: a) direction of response b) emotional intensity and elaboration of thought c) Frame of reference and content code 3. Numerous variables refer to PF 10. PF 10 is a function key used by CATI interviewers in recording comments of respondents. These side comments have been coded for this study. 4. In Wave 2 variables, respondents who were interviewed in Wave 1 but not re-interviewed in Wave 2 have had data variables padded with O's. This is not explicitly stated in the variable documentation. COGNITIVE RESPONSES TO SURVEY QUESTIONS The 1987 Pilot study carried a series of questions designed to elicit information about what is on people's minds as they respond to survey questions. The basic method was to ask individuals a standard policy question and then to use open-ended probes tofind out what exactly the individual thought about that issue. -

8/8/78-8/9/78 President's Trip To

8/8/78-8/9/78-President’s Trip to NYC [1] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 8/8/78- 8/9/78-President’s Trip to NYC [1]; Container 88 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAl:. LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT Breifj.ng Book Portion of Breifing Book dealing w/Sen. Moynihan 2 pp., personal matter 8/8/78 c ' ., oO. , ',tl," '' ' ,. II, .o FILE LOCATION Cat'ter Presidential Papers-Staff Offices,·· Office of the Staff Sec.-Presidential Handwriting File, Pres •.Trip to NYC-8/8/78-8/9/78 [1] Box 99 RESTRICJ"ION CODES (A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'governing access to national security information. (B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. (C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gl>ft. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION. NA FORM 1429 (6-85) THE SECRETARY OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE WASHINGTON, D. C. 20201 August 7, 1978 MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT FROM JOE CALIFANO� · - SUBJECT: BackgroVb� �or Your Trip to New York City This memorandum provides some background on two issues that we discussed in connection with your trip to New York City. • New York State's Hospital Cost Containment Legislation. Under Governor Carey, New York State has been a fore runner in combating runaway hospital costs. New York's program sets up categories into which groups of comparable hospitals are placed, and then establishes a ceiling on rate increases for each category. -

Presidential Files; Folder: 10/13/78; Container 95

10/13/78 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 10/13/78; Container 95 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf ·:,g~zk>t'>/ THE PRESIDENT'S SCHEDULE Friday October 13, 1978 7:30 Breakfast with Vice President Walter F. Mondale, (90 min.) Secretaries Cyrus Vance and Harold Brown, Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Mr. Hamilton Jordan. · The Cabinet Room. 9:00 Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski The Oval Office. 9~30 Signing Ceremony for S. 2640, Civil Service (15 min.) Reform. (Mr. Frank Moore) - State Dining Room. ~ . 9:45 Mr. Frank Moore The Oval Office. 10:00 . Senator Daniel P. Moynihan. (Mr. Frank Moore). (.15 min.) Tile Oval Office... • 10:30 • Mr. Jody Powell The Oval Office. • 11:00 Mr. Charles Schultze The Oval Office-. (20 min.) 11:45 Private Luncheon - The Roosevelt Room. (60 min.) 1:15 ~- Editors Meeting. (Mr. Jody Powell} - Cabinet Room: · {30 min.) ,, " I\ 2:30 Drop-by Annual Meeting of the National Alliance {15 min.) o.f Business, Inc. (Mr. Stuart Eizenstat) • Room 450, EOB. 2:45 Depart South Grounds via Helicopter en route Camp David. EledmetatJc eQ~JY Made ~or Preiervatl~n Pull'pOHI THE WHITE HOUS·E WASHINGTON October 12, 1978 MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT FROM: Walt WurW SUBJECT: Your Q&A ses:sion with non-Washing.ton editors and broadcasters -- 1:15 p .. m.. Friday, Oct. 13', Cabinet Room. Stu Eizenstat, Scotty Campbell and Sarah Weddington will brief this g.roup before they mee.t with you. Zbigniew Brzezinski and Lyle Gramley are on the a·fternoon agenda .