The Labouring Woman in Hindi Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unclaimed Dividend Details of 2019-20 Interim

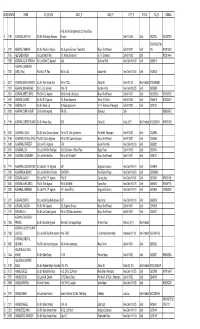

LAURUS LABS LIMITED Dividend UNPAID REGISTER FOR THE YEAR INT. DIV. 2019-20 as on September 30, 2020 Sno Dpid Folio/Clid Name Warrant No Total_Shares Net Amount Address-1 Address-2 Address-3 Address-4 Pincode 1 120339 0000075396 RAKESH MEHTA 400003 1021 1531.50 104, HORIZON VIEW, RAHEJA COMPLEX, J P ROAD, OFF. VERSOVA, ANDHERI (W) MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 400061 2 120289 0000807754 SUMEDHA MILIND SAMANGADKAR 400005 1000 1500.00 4647/240/15 DR GOLWALKAR HOSPITAL PANDHARPUR MAHARASHTRA 413304 3 LLA0000191 MR. RAJENDRA KUMAR SP 400008 2000 3000.00 H.NO.42, SRI VENKATESWARA COLONY, LOTHKUNTA, SECUNDERABAD 500010 500010 4 IN302863 10001219 PADMAJA VATTIKUTI 400009 1012 1518.00 13-1-84/1/505 SWASTIK TOWERS NEAR DON BASCO SCHOOL MOTHI NAGAR HYDERABAD 500018 5 IN302863 10141715 N. SURYANARAYANA 400010 2064 3096.00 C-102 LAND MARK RESIDENCY MADINAGUDA CHANDANAGAR HYDERABAD 500050 6 IN300513 17910263 RAMAMOHAN REDDY BHIMIREDDY 400011 1100 1650.00 PLOT NO 11 1ST VENTURE PRASANTHNAGAR NR JP COLONY MIYAPUR NEAR PRASHANTH NAGAR WATER TANK HYDERABAD ANDHRA PRADESH 500050 7 120223 0000133607 SHAIK RIYAZ BEGUM 400014 1619 2428.50 D NO 614-26 RAYAL CAMPOUND KURNOOL DIST NANDYAL Andhra Pradesh 518502 8 120330 0000025074 RANJIT JAWAHARLAL LUNKAD 400020 35 52.50 B-1,MIDDLE CLASS SOCIETY DAFNALA SHAHIBAUG AHMEDABAD GUJARAT 38004 9 IN300214 11886199 DHEERAJ KOHLI 400021 80 120.00 C 4 E POCKET 8 FLAT NO 36 JANAK PURI DELHI 110058 10 IN300079 10267776 VIJAY KHURANA 400022 500 750.00 B 459 FIRST FLOOR NEW FREINDS COLONY NEW DELHI 110065 11 IN300206 10172692 NARESH KUMAR GUPTA 400023 35 52.50 B-001 MAURYA APARTMENTS 95 I P EXTENSION PATPARGANJ DELHI 110092 12 IN300513 14326302 DANISH BHATNAGAR 400024 100 150.00 67 PRASHANT APPTS PLOT NO 41 I P EXTN PATPARGANJ DELHI 110092 13 IN300888 13517634 KAMNI SAXENA 400025 20 30.00 POCKET I 87C DILSHAD GARDEN DELHI . -

Tumhein Dil Se Kaise Juda Hum Karain Gay Mp3 Download

Tumhein dil se kaise juda hum karain gay mp3 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD · Tumhein Dil Se Kaise Juda Hum Karenge Full Song _ Doodh Ka Karz _ Jackie Shroff, Neelam. pitersondavid. Tumhein Hum Bahut Pyar. Honest Liar. Tumhein Hum Bahut Pyar. Punjabi Meego. Hum Aise karenge pyar - Jaan. Bolly HD renuzap.podarokideal.ru Tumhein dillagi bhool jani pare gi Muhabbat ki raahon mein aa kar to dekho Tarapne pe mere na phir tum hanso ge Tarapne pe mere na phir tum hanso ge Kabhi dil kissi se laga kar to dekho Honton ke paas aye hansi, kya majaal hai Dil ka muamla hai koi dillagi nahin Zakhm pe zakhm kha ke ji Apne lahoo ke ghont pi Aah na kar labon ko si Ishq hai renuzap.podarokideal.ru+tumhe+dillagi+bhool. Mere Dil Ko Tere Dil Ki Mp3 Downloadrenuzap.podarokideal.ru Explore Trending Bollywood hits back to back featuring Guru Randhawa, Arijit Singh, Mohit Chauhan, Zubin Nautiyal & many more. Our algorithm automatically provides quality content to explore based on your likes. CatchItFirst!renuzap.podarokideal.ru A site about ziaraat of Muslim religious sites with details, pictures, nohas, majalis and renuzap.podarokideal.ru Kaise kare online business kamayi internet youtube se paise kaise kamaye youtube se song video kaise download upload kare ladki se dosti, ladki ko propose impress Pyar ka izhar kaise kare friendship, bridal makeup kaise kare exam ki taiyari study renuzap.podarokideal.ru · Download Koi Apna Nahi Mp3 Mp3 Sound. Nikala Nahi Jata Kisi Ko Dil Se Shab - Love Motivational Whatsapp Status Video Status Video Song Free Download, Nikala Nahi -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Basu Chatterjee (1930 - )

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D. BASU CHATTERJEE (1930 - ) LIFE Basu Chatterjee came from a middle-class family in Rajasthan, where his father worked for the railway department. While studying in Ajmer, he went to the cinema and fell in love with films. After graduating, he went to Bombay and worked there as a cartoonist and illustrator for the weekly magazine Blitz, while at the same time continuing to watch films. After a long 18 years on the magazine, he got a job as assistant director in 1966. In 1969, he directed The Whole Sky (Sara Akash), which won many awards and is still often ranked in the top fifty Indian films of all time. Over the 1970s and 1980s, Chatterjee became one of the most popular directors in Indian cinema, primarily by making films about the lives of ordinary people. He often focused on romance and marriage, always with a light touch but raising the level of the rom-com to new levels in India. Chatterjee also had a successful career directing shows for television. He two daughters, one of whom, Rupali Guha, is also a film director. ACHIEVEMENTS Basu Chatterjee won many prizes at the National Film Awards ceremony in New Delhi, including Best Director for Swami in 1978, Best Movie for Tuberose (Rajnigandha) in 1975, and Best Screenplay for The Whole Sky (Sara Akash) in 1972 and A Small Matter (Chhoti Si Baat) in 1976. FEATURE FILMS (as director) 1969 The Whole Sky (Sara Akash) 1972 My Beloved’s House (Piya ka Ghar) 1974 Tuberrose (Rajnigandha) 1974 Beyond (Us Paar ) 1976 Heart Stealer (Chitchor ) 1976 A -

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

List of Candidates Eligible for Draw on 02.02.2019 at 2:30 Pm

LIST OF CANDIDATES ELIGIBLE FOR DRAW ON 02.02.2019 AT 2:30 PM APPLICANT Distance_Po Sibling_P Parent_Alu S.NO APPLICANT NAME GENDER DOB FATHER NAME MOTHER NAME ADDRESS PINCODE Total _Point Remarks ID int oint mni_point A 202 CROWN APARTMENT PLOT NO 18B SECTOR 7 1 7 RUDRA JAGDISH Male 4/6/2015 N JAGDISH GAYATHRI JAGDISH DELHI 110075 70 0 0 70 DWARKA SHRIYANS NARAYAN FLAT NO-6B, POCKET-1 DDA SFS FLAT, SECTOR-7 2 12 Male 5/19/2015 SANTOSH KUMAR RINKU DEVI DELHI 110075 70 0 0 70 PRASAD DWARKA, NEW DELHI-110075 3 13 DAIWIK MAHAJAN Male 9/10/2015 SHREY MAHAJAN HEENA MAHAJAN A-101 ASTHA APARTMENT PLOT NO-19B DELHI 110075 70 0 0 70 4 14 AARNA MATHUR Female 6/10/2015 NITIN MATHUR TULIKA MATHUR RZD-22 STREET NO-5 MAHAVIR ENCLAVE-1 DELHI 110045 50 20 0 70 5 17 AARADHYA DUTTA Female 2/13/2016 AJAY DUTTA ANJU DUTTA A-1/276 MADHU VIHAR NEAR SEC-2 DWARKA DELHI 110059 50 20 0 70 B-603, SARVE SATYAM APARTMENT, PLOT NO. 12, 6 19 ANAYA GARG Female 2/17/2016 GIRISH JAIN RICHA JAIN DELHI 110078 70 0 0 70 SECTOR-4 DWARKA 281,UNITED APARTMENTS, SECTOR 4, PLOT 34, 7 23 ALANKRITA GHOSH Female 11/12/2015 ABHISHEK GHOSH SHRADDHA GHOSH DELHI 110078 70 0 0 70 DWARKA, 284, PLOT - 11 AIR FORCE AND NAVAL OFFICERS 8 25 TARA SAHARAWAT Female 12/21/2015 SATYA SAHARAWAT ANAM KAUSHAL DELHI 110075 70 0 0 70 ENCLAVE SECTOR - 7 DWARKA NEW DELHI AADHYA MANAS FLAT NO. -

1811 , 21/08/2017 Class 32 2264162 10/01/2012

Trade Marks Journal No: 1811 , 21/08/2017 Class 32 2264162 10/01/2012 R.DURAIRAJ, M. RAJESWARI DURAIRAJ trading as ;MOTHER INDIA FARMS FLAT F1, 5TH FLOOR, MURUGESHPALYA, OLD AIRPORT ROAD, KODIHALLI, BANGALORE - 560 017, KARNATAKA, INDIA SERVICE PROVIDER - Address for service in India/Attorney address: NAVEEN TAO U-48,1ST FLOOR PIPLINE MAIN ROAD, MALLESHWARAM, BANGALORE - 560003 Used Since :15/12/2011 CHENNAI BEERS, MINERAL AND AERATED WATERS, AND OTHER NON-ALCOHOLIC DRINKS; FRUIT JUICES; SYRUPS AND OTHER PREPARATIONS FOR MAKING BEVERAGES. Subject to no exclusive right to the descriptive words except substantially as shown on the form of representation.. 4282 Trade Marks Journal No: 1811 , 21/08/2017 Class 32 2273918 30/01/2012 NALINI.R trading as ;KANCHIPURAM (DT,) PINCODE - 603 001, TAMILNADU, INDIA NO: 245, PALAVELI SALAI, PALAVELI VILLAGE, KATTANKULATHUR BLOCK, CHENGALPET (TK), KANCHIPURAM (DT,) PINCODE - 603 001, TAMILNADU, INDIA MANUFACTURES Address for service in India/Agents address: C. VENKATASUBRAMANIAM. S-3 AND S-4, 2ND FLOOR, RUKMINI PLAZA, NO. 84, D.V.G. RD., BASAVANGUDI, BANGLORE-560 004. Used Since :20/01/2012 CHENNAI PACKAGED DRINKING WATER THIS IS SUBJECT TO CONFINING SALES ONLY IN THE STATE OF TAMIL NADU AND UNION TERRITORY OF PONDICHERRY.. 4283 Trade Marks Journal No: 1811 , 21/08/2017 Class 32 2881938 13/01/2015 SANZI COMMERCIO GERAL IMPORTACAO E EXPORTACAO Noble Group Limitada,Rua Kalife Bairro Kawelele,Disvio De Cimangola,2nd Floor, Kicolo-Cacuaco, Luanda, Angola. Importers and Exporters. Address for service in India/Agents address: SHAH & SHAH 654, JAGANNATH SHANKRSHET MARG, MUMBAI - 400 002. Used Since :01/12/2012 MUMBAI Beers and Non-alcoholic Beverages. -

53 Skydj Karaoke List

53 SKYDJ KARAOKE LIST - BHANGRA + BOLLYWOOD FULL LIST 1 ARTIST/MOVIE TITLE ORDER Kuch Na Kaho (Inc Video) 1942 A Love Story (1994) - Singa 92039 Ruth Na Jaana 1942 Love Story - Karaoke 91457 Ruth Na Jaana 1942 Love Story - Singalong 91458 Aal Izz Well 3 Idiots 90047 Behti Hawa Sa Tha Woh 3 Idiots 90048 Give Me Some Sunshine 3 Idiots 90049 Jaana Nahi Denga Tujhe 3 Idiots 90050 Zoobi Doobi 3 Idiots 90051 All Izz Well 3 Idiots - Karaoke 92129 Jawani O Diwan Aaan Milo Sajna - Karaoke 90559 Jawani O Diwan Aaan Milo Sajna - Singalong 90560 Babuji Dheere Chalana Aaar Paar (1954) - Karaoke 92131 Aaj Purani Rahon Se Aadami - Karaoke 90257 Aaj Purani Rahon Se Aadami - Singalong 90258 Sinzagi Ke Rang Aadmi Aur Insaan - Karaoke 90858 Sinzagi Ke Rang Aadmi Aur Insaan - Singalong 90859 Aaj Mere Yaar Ki Shadi Hai Aadmi Sadak Ka - Karaoke 90259 Aaj Mere Yaar Ki Shadi Hai Aadmi Sadak Ka - Singalong 90260 Tota Meri Tota Aaj Ka Gunda Raaj - Karaoke 91157 Tota Meri Tota Aaj Ka Gunda Raaj - Singalong 91158 Ek Pappi De De Aaj Ka Gundarraj - Karaoke 90261 Ek Pappi De De Aaj Ka Gundarraj - Singalong 90262 Aaja Nachle Aaja Nachle 90053 Aaja Nachle - Inc English Trans Aaja Nachle 90052 Aaja Nachle Aaja Nachle - Karaoke 91459 Is Pal Aaja Nachle - Karaoke 91461 Ishq Hua Aaja Nachle - Karaoke 91463 Show me your Jalwa Aaja Nachle - Karaoke 91465 Aaja Nachle Aaja Nachle - Singalong 91460 Is Pal Aaja Nachle - Singalong 91462 Ishq Hua Aaja Nachle - Singalong 91464 Show me your Jalwa Aaja Nachle - Singalong 91466 Tujhe Kya Sunaun Aakhir Deo - Karaoke 91159 Tujhe Kya Sunaun -

Annual Return 2019-20

FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of rule 11of the Companies (Management and Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company (ii) (a) Name of the company (b) Registered office address (c) *e-mail ID of the company (d) *Telephone number with STD code (e) Website (iii) Date of Incorporation (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Page 1 of 15 Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2019 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM 30/09/2020 (b) Due date of AGM 30/09/2020 (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No II. PRINCIPAL BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF THE COMPANY *Number of business activities 1 S.No Main Description of Main Activity group Business Description of Business Activity % of turnover Activity Activity of the group code Code company G G2 III. PARTICULARS OF HOLDING, SUBSIDIARY AND ASSOCIATE COMPANIES (INCLUDING JOINT VENTURES) *No. -

1 Advance Cause List of Cases (Applt. Side)

06.04.2021 1 ADVANCE CAUSE LIST OF CASES (APPLT. SIDE) MATTERS LISTED FOR 06.04.2021 COURT NO.01 DIVISION BENCH-I HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE JASMEET SINGH [NOTE: IN CASE ANY ASSISTANCE REGARDING VIRTUAL HEARING IS REQUIRED, PLEASE CONTACT, MR. VIJAY RATTAN SUNDRIYAL (PH: 9811136589) COURT MASTER & MR. VISHAL (PH 9968315312) ASSISTANT COURT MASTER TO HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE & PLEASE CONTACT, MR.MANMOHAN MEHRA ,ACM (PH 9958892731) AND MR. JITENDER, RESTORER(PH 9711690023) TO HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE JASMEET SINGH.] [NOTE:THIS BENCH IS CONDUCTING PHYSICAL HEARING TODAY, HOWEVER , IF ANY ADVOCATE/PARTY DESIROUS OF JOINING THEIR MATTER THROUGH V.C., THEY MAY JOIN THE SAME USING FOLLOWING LINK MEETING LINK : https://delhihighcourt.webex.com/delhihighcourt/j.php?MTID=mef257c0be6cb885dfcca86db1f12cf0d MEETING NUMBER: 184 404 9754 Password: 1234 [NOTE: ALL COUNSEL/PARTIES ARE REQUESTED TO KEEP THEIR WEB CAMERA OFF AND MIC MUTED UNLESS THEIR MATTER IS GOING ON] FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. W.P.(C) 1034/2021 SYED MAAZ AHMED SHANKAR NARAYANAN Vs. CAMBRIDGE SCHOOL SRINIVASPURI & ANR. ADVOCATE DETAILS FOR ABOVE CASE shankar narayanan([email protected])(9650853323)(Petitioner) ashok([email protected])(9810011826)(Respondent) SYED MAAZ AHMED([email protected])(9971838056)(Respondent) SYED MAAZ AHMED([email protected])(9971838056)(Respondent) CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION([email protected])(1122509256)(Respondent) CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION([email protected])(1122509256)(Respondent) CAMBRIDGE SCHOOL SRINIVASPURI([email protected])(1126331643)(Respondent) CAMBRIDGE SCHOOL SRINIVASPURI([email protected])(1126331643)(Respondent) 2. W.P.(C) 2821/2021 GP. -

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02-2018 108 TEERTH YATRA Sony Wah TV004 07-05-2017 1234 Zee Talkies HD TV005 18-06-2017 13 NO TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla HD TV006 27-09-2015 13 NUMBER TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla Cinema TV007 25-08-2016 2012 RETURNS Zee Action TV008 02-07-2015 22 SE SHRAVAN Jalsha Movies TV009 04-04-2017 22 SE SRABON Jalsha Movies HD TV010 24-09-2016 27 DOWN Zee Classic TV011 26-12-2018 27 MAVALLI CIRCLE Star Suvarna Plus TV012 28-08-2016 3 AM THE HOUR OF THE DEAD Zee Cinema HD TV013 04-01-2016 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIKA Zee Talkies TV014 22-06-2017 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIYKA Zee Talkies TV015 21-02-2016 3 GUTTU ONDHU SULLU ONDHU Star Suvarna TV016 12-05-2017 3 GUTTU ONDU SULLU ONDU NIJA Star Suvarna Plus TV017 26-08-2017 31ST OCTOBER STAR Gold Select HD TV018 25-07-2015 3G Sony MIX TV019 01-04-2016 3NE CLASS MANJA B COM BHAGYA Star Suvarna TV020 03-12-2015 4 STUDENTS STAR Vijay TV021 04-08-2018 400 Star Suvarna Plus TV022 05-11-2015 5 IDIOTS Star Suvarna Plus TV023 27-02-2017 50 LAKH Sony Wah TV024 13-03-2017 6 CANDLES Zee Tamil TV025 02-01-2016 6 MELUGUVATHIGAL Zee Tamil TV026 05-12-2016 6 TA NAGAD Jalsha Movies TV027 10-01-2016 6-5=2 Star Suvarna TV028 27-08-2015 7 O CLOCK Zee Kannada TV029 02-03-2016 7 SAAL BAAD Sony Pal TV030 01-04-2017 73 SHAANTHI NIVAASA Zee Kannada TV031 04-01-2016 73 SHANTI NIVASA Zee Kannada TV032 09-06-2018 8 THOTAKKAL STAR Gold HD TV033 28-01-2016 9 MAHINE 9 DIWAS Zee Talkies TV034 10-02-2018 A Zee Kannada TV035 20-08-2017 -

1St Filmfare Awards 1953

FILMFARE NOMINEES AND WINNER FILMFARE NOMINEES AND WINNER................................................................................ 1 1st Filmfare Awards 1953.......................................................................................................... 3 2nd Filmfare Awards 1954......................................................................................................... 3 3rd Filmfare Awards 1955 ......................................................................................................... 4 4th Filmfare Awards 1956.......................................................................................................... 5 5th Filmfare Awards 1957.......................................................................................................... 6 6th Filmfare Awards 1958.......................................................................................................... 7 7th Filmfare Awards 1959.......................................................................................................... 9 8th Filmfare Awards 1960........................................................................................................ 11 9th Filmfare Awards 1961........................................................................................................ 13 10th Filmfare Awards 1962...................................................................................................... 15 11st Filmfare Awards 1963.....................................................................................................