Sueiviritedirc) Iiti3<Crru4jonu^4Tre;I3/I(:Iil;Rif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

227-Newsletter.Pdf

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.org APR/MAY 2011 #227 LETTERS POEM NATHANIEL MACKEY INTERVIEW CARLA HARRYMAN & LYN HEJINIAN TALK WITH CORINA COPP CALENDAR PATRICK JAMES DUNAGAN REVIEWS CHAPBOOKS BY ARIEL GOLDBERG, JESSICA FIORINI, JIM CARROLL, ALLI WARREN & NICHOLAS JAMES WHITTINGTON CATHERINE WAGNER REVIEWS ANDREA BRADY CACONRAD REVIEWS SUSIE TIMMONS FARRAH FIELD REVIEWS PAUL LEGAULT CARLEY MOORE REVIEWS EILEEN MYLES ERIK ANDERSON REVIEWS RENEE GLADMAN DAVID BRAZIL REVIEWS MINA PAM DICK STEPHANIE DICKINSON REVIEWS LEWIS WARSH MATT LONGABUCCO REVIEWS MIŁOSZ BIEDRZYCKI JAMIE TOWNSEND REVIEWS PAUL FOSTER JOHNSON ABRAHAM AVNISAN REVIEWS CAROLINE BERGVALL NICOLE TRIGG REVIEWS JULIANA LESLIE ERICA KAUFMAN REVIEWS KARINNE KEITHLEY $5? 02 APR/MAY 11 #227 THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER EDITOR: Corina Copp DISTRIBUTION: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR: Arlo Quint PROGRAM ASSISTANT: Nicole Wallace MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Macgregor Card MONDAY NIGHT TALK SERIES COORDINATOR: Michael Scharf WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Joanna Fuhrman FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATORS: Brett Price SOUND TECHNICIAN: David Vogen VIDEOGRAPHER: Alex Abelson BOOKKEEPER: Stephen Rosenthal ARCHIVIST: Will Edmiston BOX OFFICE: Courtney Frederick, Kelly Ginger, Vanessa Garver INTERNS: Nina Freeman, Stephanie Jo Elstro, Rebecca Melnyk VOLUNTEERS: Jim Behrle, Rachel Chatham, Corinne Dekkers, Ivy Johnson, Erica Kaufman, Christine Kelly, Ace McNamara, Annie Paradis, Christa Quint, Judah Rubin, Lauren Russell, Thomas Seely, Erica Wessmann, Alice Whitwham, Dustin Williamson The Poetry Project Newsletter is published four times a year and mailed free of charge to members of and contributors to the Poetry Project. Subscriptions are available for $25/year domestic, $45/year international. -

Book of Abstracts

Fourth Biennial EAAS Women’s Network Symposium Feminisms in American Studies in/and Crisis: Where Do We Go from Here? April 28 and 29, 2021 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS EAAS Women’s Network [email protected] http://women.eaas.eu IN COLLABORATION WITH 2 INTERSECTIONAL FEMINISM AND LITERATURE: THINKING THROUGH “UGLY FEELINGS”? Gabrielle Adjerad In light of what has been institutionalized in the nineties as “intersectionality” (Crenshaw, 1989), but emanated from a long tradition of feminism fostered by women of color (Hill-Collins, Bilge, 2016), feminist theory has increasingly shed light on the plurality of women’s experiences, the inseparable, overlapping and simultaneous differences constituting their identities, and the materiality of the various dominations engendered. At the turn of the twenty-first century, this paradigm seems compelling to address fictional diasporic narratives addressing the diverse discriminations encountered by migrant women and their descendants in the United States. However, adopting an intersectional feminist approach of literature, for research or in the classroom, raises methodological issues that this paper contends with. Some thinkers have considered the double pitfall of considering, on the one hand, the text as a mimetic document of plural lives and, on the other, of essentializing a symbolical “écriture feminine” (Felski, 1989). Some have highlighted the necessary critical movement between the archetypal dimension of gender and the social and historical individuals diversely affected by this ideology (De Lauretis, 1987). Yet, beyond this tension between an attention paid to abstraction on the one hand and experience on the other, we can consider that hegemony is made of different ideologies that may contradict one another (Balibar, Wallerstein, 1991). -

Book Page : Nebraska Press

Nebraska fall / winter 2020 Contents Support the Press General Interest 2 Help the University of Nebraska Press continue its New in Paperback/Trade 54 vibrant program of publishing scholarly and regional Scholarly Books 63 books by becoming a Friend of the Press. Distribution 92 To join, visit nebraskapress.unl.edu or contact New in Paperback/Scholarly 95 Erika Kuebler Rippeteau, grants and development Journals 102 specialist, at 402-472-1660 or [email protected]. Index 103 To find out how you can help support a particular Ordering Information 104 book or series, contact Donna Shear, Press director, at 402-472-2861 or [email protected]. Ebooks are available for every title unless otherwise indicated. Subject Guide African American History 59, 96, 100 History/American West 4–5, 7–9, 46, 68, Nebraska 21–23, 78 74, 76–77, 96, 101 American Studies 49, 86, 100 Philosophy 53, 85 History/World 39, 42, 51, 81, 90 Anthropology 68–69, 96–98 Poetry 10, 24 Jewish History & Culture 1, 40, 51, Archaeology 69, 96 53–54, 61, 81 Political Science 35, 39–41, 50, 67 Art & Photography 34, 48, 72 Journalism 19, 31, 36 Psychology 85, 92 Bible Study 52–53 Language Arts & Disciplines 73, 97–98 Quarantine Methods 93 Biography 9, 39, 49, 57, 61, 65, 69, 83 Latin American History 74–76, 83, Reference 73, 98–99 Communicable Disease Control 93 96–97, 100 Religion 42, 53 Creative Nonfiction 21, 25, 27–28 Linguistics 73, 97–99 Sports 6–7, 12–17, 22, 58–61, 64 Cultural Criticism & Theory 48, 80, Literary Criticism 65, 80, 86–90, 97 Travel & Tourism 2, 8, 75 82, 86 Media -

Women and Ecopoetics: an Introduction in Context

Harriet Tarlo Women and ecopoetics: an introduction in context This introduction contextualises and introduces the material within the special feature on women and ecopoetics as well as exploring the contributors’ and, on occasion, my own thoughts on the subject. I shall identify some common creative practices and ideological threads whilst respecting the sheer diversity of practitioners and practice presented here. After all, this issue features essays, statements, images, open form poetry, performance pieces, prose poetry, site specific work and found poetry from writers with experience as poets, critics, artists, educators, librarians and media workers. I have organised this work into sections as follows: Poems (selections of work from seven women poets); Recycles (selections of work making use of found text from eight women poets); Essays (seven essays on women poets from an eco-poetical perspective) and Working Notes/Ecopoetical statements. In addition to the working notes from featured poets which take the form traditional in How2, this section contains a number of short statements from writers made in response to the women and ecopoetics theme. Those that stand well alone also appear as “postcards” which has had the added advantage of their acting as a provocative “trail” for the special feature, as well as being a part of it of course. Generic segregation and classification of contents is, in some ways, contrary to the spirit of How2 and perhaps to ecopoetics too, yet it is I think helpful to reading work online to have some method of navigating our way around it. However, I should like to draw attention to the particularly hybrid nature of many of the contributions here. -

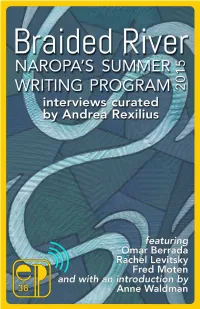

Rexilluslt Spreads1.Pdf

BRAIDED RIVER interviews curated by ANDREA REXILIUS #38 ESSAY PRESS LISTENING TOUR As the Essay Press website re-launches, we have commissioned some of our favorite conveners of public discussions to curate conversation-based CONTENTS chapbooks. Overhearing such dialogues among poets, prose writers, critics and artists, we hope to re-envision how Essay can emulate and expand upon recent developments in trans-disciplinary small-press culture. Introduction v by Anne Waldman Series Editors Maria Anderson Interview with Rachel Levitsky 1 Andy Fitch Interview with Fred Moten 20 Ellen Fogelman Aimee Harrison Interview with Omar Berrada 24 Courtney Mandryk Afterword 46 Victoria A. Sanz by Andrea Rexilius Travis Sharp Acknowledgments 50 Ryan Spooner Randall Tyrone About Naropa 2016 51 Author Bios 52 Series Assistants Cristiana Baik Ryan Ikeda Christopher Liek Cover Image Courtesy of Jane Dalrymple-Hollo Cover Design Courtney Mandryk Layout Aimee Harrison INTRODUCTION — Anne Waldman SWP Artistic Directior hese are three interviews, the same questions Tfor three eminent, wildly progressive poets who have been guest faculty during Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics Summer Writing Program—all visiting/teaching/performing at Naropa before these conversations took place, but queried here specifically in the context of our 2015 pedagogy, which carried the themic rubric of Braided River, the Activist Rhizome. Symbiosis (= “together living”) teaches that life is more like a braided river, horizontal waterflow with tributaries falling apart and coming together again (as algae, as fungi do), rather than the Abrahamic tree of life with its vertical, hierarchical branch system. We are the riparians alongside, inside, riding this river of inter- connectivity. -

235-Newsletter.Pdf

The Poetry Project Newsletter Editor: Paul Foster Johnson Design: Lewis Rawlings Distribution: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff Artistic Director: Stacy Szymaszek Program Coordinator: Arlo Quint Program Assistant: Nicole Wallace Monday Night Coordinator: Simone White Monday Night Talk Series Coordinator: Corrine Fitzpatrick Wednesday Night Coordinator: Stacy Szymaszek Friday Night Coordinator: Matt Longabucco Sound Technician: David Vogen Videographer: Andrea Cruz Bookkeeper: Lezlie Hall Archivist: Will Edmiston Box Office: Aria Boutet, Courtney Frederick, Gabriella Mattis Interns/Volunteers: Mel Elberg, Phoebe Lifton, Jasmine An, Davy Knittle, Olivia Grayson, Catherine Vail, Kate Nichols, Jim Behrle, Douglas Rothschild Volunteer Development Committee Members: Stephanie Gray, Susan Landers Board of Directors: Gillian McCain (President), John S. Hall (Vice-President), Jonathan Morrill (Treasurer), Jo Ann Wasserman (Secretary), Carol Overby, Camille Rankine, Kimberly Lyons, Todd Colby, Ted Greenwald, Erica Hunt, Elinor Nauen, Evelyn Reilly and Edwin Torres Friends Committee: Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Will Creeley, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Bob Holman, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Patricia Spears Jones, Eileen Myles, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Paul Slovak, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Anne Waldman, Hal Willner, John Yau Funders: The Poetry Project’s programs and publications are made possible, in part, with public funds from The National Endowment for the Arts. The Poetry Project’s programming is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Poetry Project’s programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council. -

2019 27Th Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog

2019 27th Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog Poets House | 10 River Terrace | New York, NY 10282 | poetshouse.org ELCOME to the 2019 Poets House Showcase, our annual, all-inclusive exhibition of the most recent poetry books, chapbooks, broadsides, artists’ books, and multimedia works published in the United States and abroad. This year marks the 27th anniversary of the Poets House Showcase and features over 3,300 books from more than 800 different presses and publishers. For 27 years, the Showcase has helped to keep our collection Wcurrent and relevant, building one of the most extensive collections of poetry in our nation—an expansive record of the poetry of our time, freely available and open to all. Building the Exhibit and the Poets House Library Collection Every year, Poets House invites poets and publishers to participate in the annual Showcase by donating copies of poetry titles released since January of the previous year. This year’s exhibit highlights poetry titles published in 2018 and the first part of 2019. Books have been contributed by the entire poetry community, from the publishers who send on their titles as they’re released, to the poets who mail us signed copies of their newest books, to library visitors donating books when they visit us. Every newly published book is welcomed, appreciated, and featured in the Showcase. The Poets House Showcase is the mechanism through which we build our library: a comprehensive, inclusive collection of over 70,000 poetry works, all free and open to the public. To make it as extensive as possible, we reach out to as many poetry communities and producers as we can, bringing together poetic voices of all kinds to meet the different needs and interests of our many library patrons. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

The Poetry Project Newsletter

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER $5.00 #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 How to Be Perfect POEMS BY RON PADGETT ISBN: 978-1-56689-203-2 “Ron Padgett’s How to Be Perfect is. New Perfect.” —lyn hejinian Poetry Ripple Effect: from New and Selected Poems BY ELAINE EQUI ISBN: 978-1-56689-197-4 Coffee “[Equi’s] poems encourage readers House to see anew.” —New York Times The Marvelous Press Bones of Time: Excavations and Explanations POEMS BY BRENDA COULTAS ISBN: 978-1-56689-204-9 “This is a revelatory book.” —edward sanders COMING SOON Vertigo Poetry from POEMS BY MARTHA RONK Anne Boyer, ISBN: 978-1-56689-205-6 Linda Hogan, “Short, stunning lyrics.” —Publishers Weekly Eugen Jebeleanu, (starred review) Raymond McDaniel, A.B. Spellman, and Broken World Marjorie Welish. POEMS BY JOSEPH LEASE ISBN: 978-1-56689-198-1 “An exquisite collection!” —marjorie perloff Skirt Full of Black POEMS BY SUN YUNG SHIN ISBN: 978-1-56689-199-8 “A spirited and restless imagination at work.” Good books are brewing at —marilyn chin www.coffeehousepress.org THE POETRY PROJECT ST. MARK’S CHURCH in-the-BowerY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.com #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 NEWSLETTER EDITOR John Coletti WELCOME BACK... DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. STAFF ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick PROGRAM ASSISTANT Arlo Quint 6 WRITING WORKSHOPS MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Akilah Oliver WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Stacy Szymaszek FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick 7 REMEMBERING SEKOU SUNDIATA SOUND TECHNICIAN David Vogen BOOKKEEPER Stephen Rosenthal DEVELOpmENT CONSULTANT Stephanie Gray BOX OFFICE Courtney Frederick, Erika Recordon, Nicole Wallace 8 IN CONVERSATION INTERNS Diana Hamilton, Owen Hutchinson, Austin LaGrone, Nicole Wallace A CHAT BETWEEN BRENDA COULTAS AND AKILAH OLIVER VOLUNTEERS Jim Behrle, David Cameron, Christine Gans, HR Hegnauer, Sarah Kolbasowski, Dgls. -

Fall 2004 the Wallace Stevens Journal

The Wallace Stevens Journal The Wallace The Wallace Stevens Journal Special Conference Issue, Part 1 Special Conference Vol. 28 No. 2Fall 2004 Vol. Special Conference Issue, Part 1 A Publication of The Wallace Stevens Society, Inc. Volume 28 Number 2 Fall 2004 The Wallace Stevens Journal Volume 28 Number 2 Fall 2004 Contents Special Conference Issue, Part I Celebrating Wallace Stevens: The Poet of Poets in Connecticut Edited by Glen MacLeod and Charles Mahoney Introduction —Glen MacLeod and Charles Mahoney 125 POETS ON STEVENS: INQUIRY AND INFLUENCE A Postcard Concerning the Nature of the Imagination —Mark Doty 129 Furious Calm —Susan Howe 133 Line-Endings in Wallace Stevens —James Longenbach 138 On Wallace Stevens —J. D. McClatchy 141 A Lifetime of Permissions —Ellen Bryant Voigt 146 NEW PERSPECTIVES ON STEVENS Planets on Tables: Stevens, Still Life, and the World —Bonnie Costello 150 Wallace Stevens and the Curious Case of British Resistance —George Lensing 158 Cross-Dressing as Stevens Cross-Dressing —Lisa M. Steinman 166 STEVENSIAN LANGUAGE “A Book Too Mad to Read”: Verbal and Erotic Excess in Harmonium —Charles Berger 175 Place-Names in Wallace Stevens —Eleanor Cook 182 Verbs of Mere Being: A Defense of Stevens’ Style —Roger Gilbert 191 WALLACE STEVENS AND HISTORICISM: PRO AND CON Stevens’ Soldier Poems and Historical Possibility —Milton J. Bates 203 What’s Historical About Historicism? —Alan Filreis 210 Wallace Stevens and Figurative Language: Pro and Con —James Longenbach 219 THE COLLECTED POEMS: THE NEXT FIFTY YEARS Prologues to Stevens Criticism in Fifty Years —John N. Serio 226 The Collected Poems: The Next Fifty Years —Susan Howe 231 Wallace Stevens and Two Types of Vanity —Massimo Bacigalupo 235 Position Paper: Wallace Stevens —Christian Wiman 240 Stevens’ Collected Poems in 2054 —Marjorie Perloff 242 KEYNOTE ADDRESS Wallace Stevens: Memory, Dead and Alive —Helen Vendler 247 THE WADSWORTH ATHENEUM Poets of Life and the Imagination: Wallace Stevens and Chick Austin —Eugene R. -

Susan Howe Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5q2nb4cj No online items Susan Howe Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2005 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Susan Howe Papers MSS 0201 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Susan Howe Papers Creator: Howe, Susan, 1937- Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0201 Physical Description: 29 Linear feet(69 archives boxes, 4 card file boxes, 6 oversize folders) Date (inclusive): 1942-2002 Abstract: Papers of Susan Howe, American poet. The collection consists of Howe's literary correspondence, poetry manuscripts, notes and typescripts for readings and talks, personal and working journals, recordings, research files, and art/poetry installations dating from the 1950s to 2002. Scope and Content of Collection The collection consists of Susan Howe's literary correspondence, poetry manuscripts, notes and typescripts for readings and talks, personal and working journals, recordings, research files, and art/poetry installations dating from the 1950s to 2002. The collection is arranged in three accessions: an accession processed in 1991, an accession processed in 2003, and a small additional accession of manuscripts for Coracle Press Publications acquired in 2009. Accession Processed in 1991: Correspondence, poetry manuscripts, typescripts and notes for readings and talks, personal and working journals, art/poetry installations and over 100 tape recordings from Howe's WBAI Radio program, "Poetry." Most of the material dates from the early 1970s to the mid-1980s. -

Vertiginous Space: Poetics of Disorientation in Charles Olson, Susan Howe, and Steve Mccaffery

Vertiginous Space: Poetics of Disorientation in Charles Olson, Susan Howe, and Steve McCaffery by Jason Vernon Starnes M.A. (English), University of British Columbia, 2003 B.A., University of British Columbia, 2000 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Jason Vernon Starnes 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Jason Vernon Starnes Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (English) Title of Thesis: Vertiginous Space: Poetics of Disorientation in Charles Olson, Susan Howe, and Steve McCaffery Examining Committee: Chair: Firstname Surname, Position Jeff Derksen Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Stephen Collis Supervisor Associate Professor Clint Burnham Supervisor Associate Professor Roxanne Panchasi Internal Examiner Associate Professor Department of History Lytle Shaw External Examiner Associate Professor, Department of English New York University Date Defended/Approved: November 26, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This dissertation is a critical study of how representations of space in selected post-war North American avant-garde poetry produce a poetics of disorientation. Reading space as a characteristic of postmodern experience and a medium of subjectivity in the globalizing stage of late capitalism, this study analyzes spatial poetry and the theory of the spatial turn as forms of knowledge that disclose the changing perceived spatiality of the globe and of the subject.