Council Chapter 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mortal Vs. Venial Sin

Mortal vs. Venial Sin UNIT 3, LESSON 4 Learning Goals Connection to the ӹ There are different types of sin. Catechism of the ӹ All sins hurt our relationship with God. Catholic Church ӹ Serious sin — that is, completely turning ӹ CCC 1854 away from God — is called mortal sin. ӹ CCC 1855 ӹ Less serious sin is called venial sin. ӹ CCC 1857 ӹ CCC 1858 ӹ CCC 1859 ӹ CCC 1862 ӹ CCC 1863 Vocabulary ӹ Charity ӹ Mortal Sin ӹ Venial Sin BIBLICAL TOUCHSTONES If anyone sees his brother sinning, if the sin is Be sure of this, that no immoral or impure or not deadly, he should pray to God and he will greedy person, that is, an idolater, has any give him life. This is only for those whose sin is inheritance in the kingdom of Christ and of not deadly. There is such a thing as deadly sin, God. about which I do not say that you should pray. EPHESIANS 5:5 All wrongdoing is sin, but there is sin that is not deadly. 1 JOHN 5:16-17 © SOPHIA INSTITUTE FOR TEACHERS 155 Lesson Plan Materials ӹ Failure-to-Love Slips ӹ Understanding Mortal Sin DAY ONE Warm-Up A. Ask students to recall the Good vs. Evil activity they completed earlier in the unit, and to recall some good and evil characters from their lists. Keep a list on the board. B. Based on the list, ask students again to identify the basic differences between good and evil. If necessary, lead students to the conclusion that good seeks what is best for others while evil seeks its own interests and destroys the happiness of others. -

Mhfm Is the Hoax Not COVID-19 the Dimond Brothers Calumny & Detraction Against Jorge Clavellina Over a Difference of Secular Opinion

MhFM is the Hoax Not COVID-19 The Dimond Brothers Calumny & Detraction Against Jorge Clavellina Over a Difference of Secular Opinion "Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You clean the outside of the cup and dish, but inside they are full of greed and self-indulgence. Blind Pharisee! First clean the inside of the cup and dish, and then the outside also will be clean." - St Matthew 23:25 Calumny: "Injuring another person's good name by lying." Detraction: “revealing another's sins to a third party who does not need to know about them.” The Catholic Church holds that the sins of Calumny and Detraction destroy the reputation and honor of one's neighbor. Honor is the social witness given to human dignity, and everyone enjoys a natural right to the honor of his name and reputation and to respect. Thus, detraction and calumny egregiously offend against the virtues of justice and charity. Both are mortal sins. Though Jorge Clavellina (a once devout MhFM supporter) and I stand on opposite sides of the V-II fence we none-the-less share the same position that the Dimond Brothers use the sins of Calumny and Detraction as their weapon of choice against any and all who oppose them. Jorge discovered just how debased and treacherous the Dimonds can be after quitting MhFM over a heated disagreement concerning his refusal to accept their erroneous claim that COVID-19 is a HOAX. Note: As I found Jorge’s original YouTube video "Coronavirus Fight. MHFM (vaticancatholic) FULL emails & Context" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GOU9gwo7qSc) .. -

File Downloadenglish

CURIA PRIEPOSITI GENERALIS Cur. Gen. 89/8 Jesuit Life SOCIETATIS IESU in the Spirit ROMA · Borgo S. Spirito, 5 TO THE WHOLE SOCIETY Dear Fathers and Brothers, P.C. Introduction With this letter I wish to react to numerous letters which have come to me on Life in the Spirit in the Society today. Prepared in great part with the help of a community meeting or a consultation, these letters witness to the spiritual health of the apostolic body of the Society. And they express the desire to experience a new spiritual vigor, especially with the approach of the Ignatian Year. They do not hide, though, the difficulties common to every life in the Spirit today. Such a life feels at one and the same time the effects of the strong need to live spiritually which so many of our contemporaries experience, of a whole culture in the throes of losing its taste for God, of the mentality fashioned by the currents of our times, and of the search for dubious mysticisms. The letters do not speak of life in the Spirit as if it were a reality only during moments of escape or times of rest. They are faithful to the contemplation on the Incarnation (Sp. Ex. 102 ff.) in expressing the bond which St. Ignatius considered indis pensable for every life in the Spirit: "the greater glory of God and the service of men" (Form. Inst. n.l). "In order to reach this state of contemplation, St. Ignatius demands of you that you be men of prayer," the Holy Father reminded us recently, "in order to be also teachers of prayer; at the same time he expects you to be men of mortification, in order to be visible signs of Gospel values" (John Paul II, Homily, September 2, 1983, at GC 33). -

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms

Church and Liturgical Objects and Terms Liturgical Objects Used in Church The chalice: The The paten: The vessel which golden “plate” that holds the wine holds the bread that that becomes the becomes the Sacred Precious Blood of Body of Christ. Christ. The ciborium: A The pyx: golden vessel A small, closing with a lid that is golden vessel that is used for the used to bring the distribution and Blessed Sacrament to reservation of those who cannot Hosts. come to the church. The purificator is The cruets hold the a small wine and the water rectangular cloth that are used at used for wiping Mass. the chalice. The lavabo towel, The lavabo and which the priest pitcher: used for dries his hands after washing the washing them during priest's hands. the Mass. The corporal is a square cloth placed The altar cloth: A on the altar beneath rectangular white the chalice and cloth that covers paten. It is folded so the altar for the as to catch any celebration of particles of the Host Mass. that may accidentally fall The altar A new Paschal candles: Mass candle is prepared must be and blessed every celebrated with year at the Easter natural candles Vigil. This light stands (more than 51% near the altar during bees wax), which the Easter Season signify the and near the presence of baptismal font Christ, our light. during the rest of the year. It may also stand near the casket during the funeral rites. The sanctuary lamp: Bells, rung during A candle, often red, the calling down that burns near the of the Holy Spirit tabernacle when the to consecrate the Blessed Sacrament is bread and wine present there. -

Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport

DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT Policies for Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport These pages may be reproduced by parish and Diocesan staff for their use Policy promulgated at the Pastoral Center of the Diocese of Davenport–effective September 14, 2007 Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross Revised November 27, 2011 Revised October 15, 2012 Most Reverend Martin Amos Bishop of Davenport TABLE OF CONTENTS §IV-249 POLICIES FOR IMPLEMENTING SUMMORUM PONTIFICUM IN THE DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT: INTRODUCTION 1 §IV-249.1 THE ROLE OF THE BISHOP 2 §IV-249.2 FACULTIES 3 §IV-249.3 REQUIREMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF MASS 4 §IV-249.4 REQUIREMENTS FOR THE CELEBRATION OF THE OTHER SACRAMENTS AND RITES 6 §IV-249.5 REPORTING REQUIREMENTS 6 APPENDICES Appendix A: Documentation Form 7 Appendix B: Resources 8 0 §IV-249 Policies for Implementing Summorum Pontificum in the Diocese of Davenport §IV-249 POLICIES IMPLEMENTING SUMMORUM PONTIFICUM IN THE DIOCESE OF DAVENPORT Introduction In the 1980s, Pope John Paul II established a way to allow priests with special permission to celebrate Mass and the other sacraments using the rites that were in use before Vatican II (the 1962 Missal, also called the Missal of John XXIII or the Tridentine Mass). Effective September 14, 2007, Pope Benedict XVI loosened the restrictions on the use of the 1962 Missal, such that the special permission of the bishop is no longer required. This action was taken because, as universal shepherd, His Holiness has a heart for the unity of the Church, and sees the option of allowing a more generous use of the Mass of 1962 as a way to foster that unity and heal any breaches that may have occurred after Vatican II. -

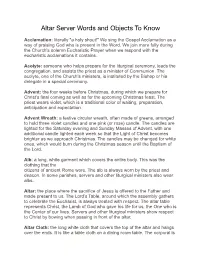

Altar Server Words and Objects to Know

Altar Server Words and Objects To Know Acclamation: literally "a holy shout!" We sing the Gospel Acclamation as a way of praising God who is present in the Word. We join more fully during the Church's solemn Eucharistic Prayer when we respond with the eucharistic acclamations it contains. Acolyte: someone who helps prepare for the liturgical ceremony, leads the congregation, and assists the priest as a minister of Communion. The acolyte, one of the Church's ministers, is instituted by the Bishop or his delegate in a special ceremony. Advent: the four weeks before Christmas, during which we prepare for Christ's final coming as well as for the upcoming Christmas feast. The priest wears violet, which is a traditional color of waiting, preparation, anticipation and expectation. Advent Wreath: a festive circular wreath, often made of greens, arranged to hold three violet candles and one pink (or rose) candle. The candles are lighted for the Saturday evening and Sunday Masses of Advent, with one additional candle lighted each week so that the Light of Christ becomes brighter as we approach Christmas. The candles may be changed for white ones, which would burn during the Christmas season until the Baptism of the Lord. Alb: a long, white garment which covers the entire body. This was the clothing that the citizens of ancient Rome wore. The alb is always worn by the priest and deacon. In some parishes, servers and other liturgical ministers also wear albs. Altar: the place where the sacrifice of Jesus is offered to the Father and made present to us. -

What Does It Mean to Be in the State of Grace?

Dear Father Kerper What does it mean to be in the state of grace? ear Father Kerper: As a boy, D I learned about the necessity of being in the “state of grace.” I’ve always wondered: What exactly does that mean? How do we know whether we’re in it or not? Your great question leads us to examine two crucial matters often overlooked. First, how should Christians understand their human condition on earth? And second, what is the connection between the earthly lives of human beings and their only possible outcomes: endless happiness and total fulfillment in eternal life (Heaven) or the perpetual anguish caused by freely choosing something other than God (Hell)? Let’s begin by correcting one terrible — but very common — misunderstanding. Many people define the “state of grace” as the absence of mortal sin. Yes, grave sin is incompatible with the “state of grace,” but this minimalistic understanding is akin to saying, “I’ve been hugely successful in life because I’ve never gone to jail.” There’s Francesco Guardi, more to life than not getting convicted The Four Evangelists and the Holy Trinity with Saints of crimes; and there’s much more to the “state of grace” than avoiding mortal sin. “There’s more to life than not getting convicted of To grasp the beauty of living in the crimes; and there’s much more to the ‘state of grace’ “state of grace,” we need a clear definition of “grace.” Simply — and shockingly — than avoiding mortal sin.” put, “grace” is God! Allow me to refine this idea: “Grace” is God in that God freely communicates himself to human proposes this idea and many Greek- point of union, somewhat like the beings, thereby enabling human beings speaking Church Fathers spoke of the marriage of a man and woman. -

Vestments and Sacred Vessels Used at Mass

Vestments and Sacred Vessels used at Mass Amice (optional) This is a rectangular piece of cloth with two long ribbons attached to the top corners. The priest puts it over his shoulders, tucking it in around the neck to hide his cassock and collar. It is worn whenever the alb does not completely cover the ordinary clothing at the neck (GI 297). It is then tied around the waist. It symbolises a helmet of salvation and a sign of resistance against temptation. 11 Alb This long, white, vestment reaching to the ankles and is worn when celebrating Mass. Its name comes from the Latin ‘albus’ meaning ‘white.’ This garment symbolises purity of heart. Worn by priest, deacon and in many places by the altar servers. Cincture (optional) This is a long cord used for fastening some albs at the waist. It is worn over the alb by those who wear an alb. It is a symbol of chastity. It is usually white in colour. Stole A stole is a long cloth, often ornately decorated, of the same colour and style as the chasuble. A stole traditionally stands for the power of the priesthood and symbolises obedience. The priest wears it around the neck, letting it hang down the front. A deacon wears it over his right shoulder and fastened at his left side like a sash. Chasuble The chasuble is the sleeveless outer vestment, slipped over the head, hanging down from the shoulders and covering the stole and alb. It is the proper Mass vestment of the priest and its colour varies according to the feast. -

Tridentine Community News July 26, 2009

Tridentine Community News July 26, 2009 In Defense of Individual Celebration of the Holy Mass side altars lining the walls of its chapel. Older churches such as our own were constructed with side altars for the same reason, to The 1983 Code of Canon Law urges priests to celebrate the Holy allow the assisting priests in residence at the parish to offer their Sacrifice of the Mass every day. Canon 276 §2 n. 2 states: own Masses each day. In an interesting sign of the times, at the “…priests are earnestly invited to offer the eucharistic sacrifice Fraternity of St. Peter’s seminary in Nebraska, priests celebrate daily…”. (Key point: It is not mandatory.) their individual Masses in a room cluttered with mismatched side altars salvaged from various churches. Priests living in a religious community, such as at a monastery, often have a regularly scheduled daily Mass. If they follow the A little-known fact is that there is one time that a priest may Ordinary Form, this Community Mass can be one in which some concelebrate at a or all of the priests concelebrate the Mass. Tridentine Mass, and that is at a If the religious community, or an individual priest, follows the Mass of Extraordinary Form, concelebration is not permitted. Each priest Ordination. Each must celebrate his own individual Mass. The below historic photo ordinand shows priests celebrating private Masses at Orchard Lake’s Ss. concelebrates the Cyril & Methodius Seminary, pre-Vatican II. Mass with the bishop. Each new priest is assisted by an experienced priest at his side, as pictured in the adjacent photo from an Institute of Christ the King ordination. -

Jesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration

JesuitsJesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration James J. Conn, S.J.S.J. Jesuits,Jesuits, the Ministerial PPriesthood,riesthood, anandd EucharisticEucharistic CConcelebrationoncelebration JohnJohn F. Baldovin,Baldovin, S.J.S.J. 51/151/1 SPRING 2019 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits is a publication of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. The Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality is composed of Jesuits appointed from their provinces. The seminar identifies and studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially US and Canadian Jesuits, and gath- ers current scholarly studies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. It then disseminates the results through this journal. The opinions expressed in Studies are those of the individual authors. The subjects treated in Studies may be of interest also to Jesuits of other regions and to other religious, clergy, and laity. All who find this journal helpful are welcome to access previous issues at: [email protected]/jesuits. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Note: Parentheses designate year of entry as a seminar member. Casey C. Beaumier, SJ, is director of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. (2016) Brian B. Frain, SJ, is Assistant Professor of Education and Director of the St. Thomas More Center for the Study of Catholic Thought and Culture at Rock- hurst University in Kansas City, Missouri. (2018) Barton T. Geger, SJ, is chair of the seminar and editor of Studies; he is a research scholar at the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies and assistant professor of the practice at the School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College. -

English-Latin Missal

ENGLISH-LATIN MISSAL International Union of Guides and Scouts of Europe © www.romanliturgy.org, 2018: for the concept of booklets © apud Administrationem Patrimonii Sedis Apostolicæ in Civitate Vaticana, 2002: pro textibus lingua latina © International Commission on English in the Liturgy Corporation, 2010: all rights reserved for the English texts The Introductory Rites When the people are gathered, the Priest approaches the altar with the ministers while the Entrance Chant is sung. Entrance Antiphon: Monday, January 29 p. 26. Tuesday, January 30 p. 27. Wednesday, January 31 p. 30. When he has arrived at the altar, after making a profound bow with the ministers, the Priest venerates the altar with a kiss and, if appropriate, incenses the cross and the altar. Then, with the ministers, he goes to the chair. When the Entrance Chant is concluded, the Priest and the faithful, standing, sign themselves with the Sign of the Cross, while the Priest, facing the people, says: In nómine Patris, et Fílii, et Spíritus In the name of the Father, and of the Sancti. Son, and of the Holy Spirit. The people reply: Amen. Amen. Then the Priest, extending his hands, greets the people, saying: Grátia Dómini nostri Iesu Christi, et The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and cáritas Dei, et communicátio Sancti the love of God, and the communion of Spíritus sit cum ómnibus vobis. the Holy Spirit, be with you all. Or: Grátia vobis et pax a Deo Patre nostro Grace to you and peace from God our et Dómino Iesu Christo. Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. -

Assisting at the Parish Eucharist

The Parish of Handsworth: The Church of St Mary: Assisting at the Parish Eucharist 1st Lesson Sunday 6th June Celebrant: The Rector Gen 3:8-15 N Gogna Entrance Hymn: Let us build a house (all are welcome) Reader: 2nd Lesson 2 Cor 4: 1st After Trinity Liturgical Deacon: A Treasure D Arnold Gradual Hymn: Jesus, where’er thy people meet Reader: 13-5:1 Preacher: The Rector Intercessor: S Taylor Offertory Hymn: There’s a wideness in God’s mercy Colour: Green MC (Server): G Walters Offertory Procession: N/A Communion Hymn: Amazing grace Thurifer: N/A N/A Final Hymn: He who would valiant be Mass Setting: Acolytes: N/A Chalice: N/A St Thomas (Thorne) Sidespersons: 8.00am D Burns 11.00am R & C Paton-Devine Live-Stream: A Lubin & C Perry 1st Lesson Ezek 17: Sunday 13th June Celebrant: The Rector M Bradley Entrance Hymn: The Church’s one foundation Reader: 22-end 2nd Lesson 2nd After Trinity Liturgical Deacon: P Stephen 2 Cor 5:6-17 A Cash Gradual Hymn: Sweet is the work my God and king Reader: Preacher: P Stephen Intercessor: R Cooper Offertory Hymn: God is working his purpose out Colour: Green MC (Server): G Walters Offertory Procession: N/A Communion Hymn: The king of love my shepherd is Thurifer: N/A N/A Final Hymn: The Kingdom of God is justice… Mass Setting: Acolytes: N/A Chalice: N/A St Thomas (Thorne) Sidespersons: 8.00am E Simkin 11.00am L Colwill & R Hollins Live-Stream: W & N Senteza Churchwarden: Keith Hemmings & Doreen Hemmings Rector: Fr Bob Stephen Organist: James Jarvis The Parish of Handsworth: The Church of St Mary: Assisting at