A Glimpse Into the External Validity Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtual Conference Sept

ADVANCES WITH FIELD EXPERIMENTS VIRTUAL CONFERENCE SEPT. 23-24, 2020 Keynote Speakers KEYNOTE SPEAKERS ORIANA BANDIERA Oriana Bandiera is the Sir Anthony Atkinson Professor of Economics and the Director of the Suntory and Toyota Centre for Economics and Related Disciplines at the London School of Economics, and a fellow of the British Academy, the Econometric Society, CEPR, BREAD and IZA. She is vice- president of the European Economic Association, and director of the Gender, Growth and Labour Markets in Low-Income Countries program and of the research program in Development Economics at CEPR. She is co-editor of Microeconomic Insights and Economica. Her research focuses on how monetary incentives and social relationships interact to shape individual choices within organizations and in labor markets. Her research has been awarded the IZA Young Labor Economist Prize, the Carlo Alberto Medal, the Ester Boserup Prize, and the Yrjö Jahnsson Award. LARRY KATZ Lawrence F. Katz is the Elisabeth Allison Professor of Economics at Harvard University and a Research Associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. His research focuses on issues in labor economics and the economics of social problems. He is the author (with Claudia Goldin) of The Race between Education and Technology (Harvard University Press, 2008), a history of U.S. economic inequality and the roles of technological change and the pace of educational advance in affecting the wage structure. Katz also has been studying the impacts of neighborhood poverty on low- income families as the principal investigator of the long-term evaluation of the Moving to Opportunity program, a randomized housing mobility experiment. -

Structural Behavioral Economics

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES STRUCTURAL BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS Stefano DellaVigna Working Paper 24797 http://www.nber.org/papers/w24797 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2018 Forthcoming in the 1st Handbook of Behavioral Economics, Vol.1, edited by Douglas Bernheim, Stefano DellaVigna, and David Laibson, Elsevier. I thank Hunt Allcott, Charles Bellemare, Daniel Benjamin, Douglas Bernheim, Colin Camerer, Vincent Crawford, Thomas Dohmen, Philipp Eisenhauer, Keith Ericson, Lorenz Goette, Johannes Hermle, Lukas Kiessling, Nicola Lacetera, David Laibson, John List, Edward O'Donoghue, Gautam Rao, Alex Rees-Jones, John Rust, Jesse Shapiro, Charles Sprenger, Dmitry Taubinsky, Bertil Tungodden, Hans-Martin von Gaudecker, George Wu, and the audience of presentations at the 2016 Behavioral Summer Camp, at the SITE 2016 conference, and at the University of Bonn for their comments and suggestions. I thank Bryan Chu, Avner Shlain, Alex Steiny, and Vasco Villas-Boas for outstanding research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2018 by Stefano DellaVigna. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Structural Behavioral Economics Stefano DellaVigna NBER Working Paper No. 24797 July 2018 JEL No. C1,C9,D03,D9 ABSTRACT What is the role of structural estimation in behavioral economics? I discuss advantages, and limitations, of the work in Structural Behavioral Economics. -

Field Experiments: a Bridge Between Lab and Naturally-Occurring Data

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES FIELD EXPERIMENTS: A BRIDGE BETWEEN LAB AND NATURALLY-OCCURRING DATA John A. List Working Paper 12992 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12992 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2007 *This study is based on plenary talks at the 2005 International Meetings of the Economic Science Association, the 2006 Canadian Economic Association, and the 2006 Australian Econometric Association meetings. The paper is written as an introduction to the BE-JEAP special issue on Field Experiments that I have edited; thus my focus is on the areas to which these studies contribute. Some of the arguments parallel those contained in my previous work, most notably the working paper version of Levitt and List (2006) and Harrison and List (2004). Don Fullerton, Dean Karlan, Charles Manski, and an anonymous reporter provided remarks that improved the study. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by John A. List. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Field Experiments: A Bridge Between Lab and Naturally-Occurring Data John A. List NBER Working Paper No. 12992 March 2007 JEL No. C9,C90,C91,C92,C93,D01,H41,Q5,Q51 ABSTRACT Laboratory experiments have been used extensively in economics in the past several decades to lend both positive and normative insights into a myriad of important economic issues. -

Mass Murder and Spree Murder

Two Mass Murder and Spree Murder Two Types of Multicides A convicted killer recently paroled from prison in Tennessee has been charged with the murder of six people, including his brother, Cecil Dotson, three other adults, and two children. The police have arrested Jessie Dotson, age 33. The killings, which occurred in Memphis, Tennessee, occurred in February 2008. There is no reason known at this time for the murders. (Courier-Journal, March 9, 2008, p. A-3) A young teenager’s boyfriend killed her mother and two brothers, ages 8 and 13. Arraigned on murder charges in Texas were the girl, a juvenile, her 19-year-old boyfriend, Charlie James Wilkinson, and two others on three charges of capital murder. The girl’s father was shot five times but survived. The reason for the murders? The parents did not want their daughter dating Wilkinson. (Wolfson, 2008) Introduction There is a great deal of misunderstanding about the three types of multi- cide: serial murder, mass murder, and spree murder. This chapter will list the traits and characteristics of these three types of killers, as well as the traits and characteristics of the killings themselves. 15 16 SERIAL MURDER Recently, a school shooting occurred in Colorado. Various news outlets erroneously reported the shooting as a spree killing. Last year in Nevada, a man entered a courtroom and killed three people. This, too, was erro- neously reported as a spree killing. Both should have been labeled instead as mass murder. The assigned labels by the media have little to do with motivations and anticipated gains in the original effort to label it some type of multicide. -

146534NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. , I .Ir. I. .--, . I \ ~ _'- ~ : ,rIP' • - , ,.~ .'~ .- 0::-" " ,1 January 1994 Volume 63 Number 1 United States Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, DC 20535 Louis J. Freeh, Features Director Contributors' opinions and statements should not be considered as an endorsement for any policy, program, or service by the Higher Education Educational standards for police FBI. for Law Enforcement personnel enhance police professionalism. {tfto ~3 3 By Michael G. Breci The Attorney General has a determined that the publication of this periodical is necessary in the transaction of the public Forensic Imaging Comes of Age Enhanced computer technology business required by law. advances the field of forensic Use of funds for printing this By Gene O'Donnell periodical has been imaging, providing lawe~'PJcement II with new capabilities. Lft0 approved by the Director of f 534 the Office of Management and Budget. Child Abuse: Understanding child development is • the key to successful interviews of The FBI Law Enforcement Interviewing Possible Victims young sexual abuse victims. Bulletin (ISSN·0014-5688) By David Gullo Em is published monthly by the /%j-:3~ Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1Dlh and Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20535. Second-Class postage paid Obtaining Consent to The use of deception to obtain at Washington, D.C., and Enter by Deception consent to enter is a useful iaw additional mailing offices. enforcement to~1f..hen legal'%.. Postmaster: Send address By John Gales Sauls employed. / S changes to FBI Law '1-6 3 8' Enforcement Bulletin, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Washington, D.C. -

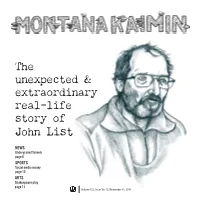

The Unexpected & Extraordinary Real-Life Story of John List

The unexpected & extraordinary real-life story of John List NEWS Underground tunnels page 6 SPORTS Social media money page 10 ARTS Shakespeare play page 12 Volume 122, Issue No. 12, November 13, 2019 KIOSK | ABOUT US OPINION | KAIMIN EDITORIAL Cover portrait Cooper Malin Cover design and illustrations Lily Johnson EDITORIAL STAFF Editor-in-Chief Arts & Culture Editors Design Editors Cassidy Alexander Erin Sargent Jaqueline Evans-Shaw Lily Soper Daylin Scott It’s not cool to not take care of yourself Business Manager Patrick Boise Multimedia Editor Sleeping is not an option. It healthy brain function,” re- work done. Let’s face it: Finals Imagine you are that person wouldn’t have to stay up until 3 Sara Diggins News & Sports Editors is a necessary human function. searchers stated in the study. week and that midterm slump who decided getting sleep was a.m. Sometimes finding the time Sydney Akridge So when you brag about not In addition, research con- can be brutal, and it’s a strug- more important than staying up in the day to go to the bathroom, Helena Dore getting enough sleep, you’re ducted by individuals at the gle to stay balanced. It’s unfair until 3 a.m. to finish a research let alone get a head start on not showing what a dedicated University of Warwick in 2010 to say every student’s stress is project. You already feel terrible homework, can be challenging. student you are. You’re showing concluded that short sleep merely the result of poor time about not having your project The truth is that we all choose The Montana Kaimin is a weekly independent student NEWSROOM STAFF how little you prioritize your increases the likelihood of management, because often done, and hearing your peers to prioritize different things, newspaper at the University of Montana. -

Enhancing the Efficacy of Teacher Incentives Through Framing: a Field Experiment*

Enhancing the Efficacy of Teacher Incentives through Framing: A Field Experiment* Roland G. Fryer, Jr. Harvard University Steven D. Levitt The University of Chicago John List The University of Chicago Sally Sadoff UC San Diego April, 2018 Abstract In a field experiment, we provide financial incentives to teachers framed either as gains, received at the end of the year, or as losses, in which teachers receive upfront bonuses that must be paid back if their students do not improve sufficiently. Pooling two waves of the experiment, loss-framed incentives improve math achievement by an estimated 0.124 standard deviations (σ) with large effects in the first wave and no effects in the second wave. Effects for gain framed incentives are smaller and not statistically significant, approximately 0.051σ. We find suggestive evidence that effects on teacher value added persist post-treatment. * Fryer: Harvard University, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, MA, 02138; [email protected]. Levitt: University of Chicago, 5807 S Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637; [email protected]. List: 5757 S. University Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637; [email protected]. Sadoff: UC San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093; [email protected]. We are grateful to Tom Amadio and the Chicago Heights teachers’ union for their support in conducting our experiment. Eszter Czibor, Jonathan Davis, Matt Davis, Sean Golden, William Murdock III, Phuong Ta and Wooju Lee provided exceptional research assistance. Financial support from the Kenneth and Anne Griffin Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. The research was conducted with approval from the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. Please direct correspondence to Sally Sadoff: [email protected]. -

DDT Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE What happened to the girl on the mountain? Death on the Devil’s Teeth is the newest addition to The History Press’ True Crime series. The book is by local authors, Jesse P. Pollack and Mark Moran and is set to release on July 20th, 2015. As Springfield residents decorated for Halloween in September 1972, the crime rate in the quiet, affluent township was at its Death on the Devil’s Teeth lowest in years. That mood was shattered when the body of sixteen The Strange Murder That Shocked -year-old Jeannette DePalma was discovered in the local woods, Suburban New Jersey allegedly surrounded by strange objects. Some feared witchcraft By Jesse P. Pollack & Mark Moran was to blame, while others believed a serial killer was on the loose. Rumors of a police coverup ran rampant, and the case went ISBN: 9781626196285 unsolved—along with the murders of several other young women. $21.99 | 208 pp. | paperback Now, four decades after Jeannette DePalma’s tragic death, authors Available: July 20, 2015 Jesse P. Pollack and Mark Moran present the definitive account of this shocking cold case. With more than 12,000 titles in print, Arcadia Publishing & The History Press is the largest and most comprehensive publisher of local and regional content in the USA. By empowering local history and culture enthusiasts to write local stories for local audiences, we create exceptional books that enrich lives and bring readers closer to their community, their neighbors, and their past. Highlights from the Book www.arcadiapublishing.com www.historypress.net. -

John A. List Interview

INTERVIEW John A. List In the 1950s, Vernon Smith — then teaching at Purdue University and influenced by the work of Edward Chamberlin, one of his instructors at Harvard University — began conducting experiments to see how people responded to various market incentives and structures in a laboratory-type environment. At first, many economists questioned the importance of those experiments’ results. But by the 1970s, others, including Charles Plott of the California Institute of Technology, began using experiments to better understand decisionmaking in various market settings, and in 2002 Smith was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics along with the psychologist Daniel Kahneman of Princeton University. In the mid-1990s, John List, who believed that experimental work had provided unique insights into human behavior, began conducting experiments of his own, but in the field rather than in the lab. By setting up carefully designed experiments with people performing tasks they are used to doing as part of their daily lives, List has been able to test how people behave in natural settings — and whether that behavior is consistent with economic theory. List’s field experiments, like Smith’s lab experiments, were initially greeted with skepticism by many economists, but that has changed over time. RF: Could you briefly describe what you mean when you List has published more than 150 articles in refereed speak about field experiments in economics — and what academic journals during the last 15 years, many on field methodological issues should economists be concerned experiments and related work. with in order to do field experiments well? List began his career at the University of Central Florida, with stops at the University of Arizona and the List: A good place to start is to think about how economists University of Maryland before arriving at the University have used measurement tools in the past. -

Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: the Art and Science of the Human Head Kourtnei F

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 10-3-2018 Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: The Art and Science of the Human Head Kourtnei F. Rodriguez [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Rodriguez, Kourtnei F., "Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: The Art and Science of the Human Head" (2018). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rodriguez - i ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Health Sciences & Technology In Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS In Medical Illustration Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: The Art and Science of the Human Head by Kourtnei F. Rodriguez October 3, 2018 Rodriguez - ii Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: The Art and Science of the Human Head Kourtnei F. Rodriguez Chief Advisor: Professor James Perkins Signature: __________________________________ Date: ____________________ Associate Advisor: Professor Glen Hintz Signature: __________________________________ Date: ____________________ Content Expert: Special Agent Walter Henson, Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) Signature: __________________________________ Date: ____________________ Vice Dean, College of Health Sciences &Technology: Dr. Richard Doolittle Signature: __________________________________ Date: ____________________ Rodriguez - iii Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Lt. Kevin Wiley from the Oakland Police Department for providing me with the initial casework for my thesis. I would also like to thank fellow forensic artist Lois Gibson for inviting me to her class, Forensic Art Techniques - Mastering Composite Drawing, at Northwestern University Center for Public Safety. -

The Dozen Things Experimental Economists Should Do (More Of)

The Dozen Things Experimental Economists Should Do (More of) Eszter Czibor,∗ David Jimenez-Gomez,y and John A. Listz February 12, 2019 x Abstract What was once broadly viewed as an impossibility { learning from experimen- tal data in economics { has now become commonplace. Governmental bodies, think tanks, and corporations around the world employ teams of experimental researchers to answer their most pressing questions. For their part, in the past two decades aca- demics have begun to more actively partner with organizations to generate data via field experimentation. While this revolution in evidence-based approaches has served to deepen the economic science, recently a credibility crisis has caused even the most ∗Department of Economics, University of Chicago, 1126 E. 59th, Chicago, IL 60637, USA; E-mail: [email protected] yDepartment of Economics, University of Alicante, Spain; Email: [email protected] zDepartment of Economics, University of Chicago, 1126 E. 59th, Chicago, IL 60637, USA; E-mail: [email protected] xThis paper is based on a plenary talk given by John List at the Economics Science Association in Tuc- son, Arizona, 2016, titled \The Dozen Things I Wish Experimental Economists Did (More Of)". We are grateful for the insightful suggestions provided by Jonathan Davis, Claire Mackevicius, Alicia Marguerie, David Novgorodsky, Julie Pernaudet and Daniel Tannenbaum, and for great comments by participants at the University of Alicante research seminar, at the Barcelona GSE Summer Forum's Workshop on Exter- nal Validity, and at the 4th Workshop on Experimental Economics for the Environment at WWU M¨unster. We thank Eric Karsten, Ariel Listo and Haruka Uchida for excellent research assistance. -

LARRY E. Mccann Vice President and Violent Crime Consultant

THIS CURRICULUM VITAE IS SENT TO YOU FOR INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY. YOU ARE NOT AUTHORIZED TO USE ANY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN FOR ANY PURPOSE OTHER THAN IN THE DETERMINATION TO CONTRACT THE SERVICES OF MR. McCANN. MISUSE OF VITAE INFORMATION BY OTHERS IN THE PAST REQUIRES US TO ADVISE YOU THAT THE WRONGFUL USE OF MR. McCANN’S NAME, SUCH AS LISTING HIM AS AN EXPERT WITNESS WITHIN THE DISCOVERY PROCESS BEFORE HE HAS AGREED TO SERVE AS AN EXPERT, IS ACTIONABLE UNLESS MR. McCANN OR THE ACADEMY GROUP, INC., GIVES PRIOR SPECIFIC PERMISSION. LARRY E. McCANN Vice President and Violent Crime Consultant The Academy Group, Inc. 7542 Diplomat Drive, Suite 201 Manassas, Virginia 20109 (703) 330-0697 Academy-Group.com Larry E. McCann Curriculum Vitae [2] INTRODUCTION For over 35 years Larry McCann has been recognized and accepted in criminal and civil courts of law as an expert in Violent Crime Analysis, Crime Scene Reconstruction and Analysis, and Bloodstain Pattern Analysis. During his tenure as a Special Agent for the Virginia State Police Bureau of Criminal Investigations, he worked in homicide, violent, and serial crime investigation. As one of only 33 worldwide graduates of the FBI Police Fellowship Program, he received formal specialized training in analyzing behavioral evidence for one year. This training contributed to the development of the Virginia Homicide Assessment and Lead Tracking System, and led Mr. McCann create the Virginia State Police Behavioral Science Services. In 1998, Janet Reno, then the United States Attorney General, appointed Mr. McCann to assist in the development of national guidelines for crime scene investigation.